Protectorate of Peru

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (June 2021) |

Protectorate of Peru Protectorado del Perú | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1821–1822 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Lima | ||||||||

| Common languages | Spanish | ||||||||

| Religion | Roman Catholic | ||||||||

| Government | Protectorate of Argentina | ||||||||

| Protector of Peru | |||||||||

• 28 July 1821-20 September 1822 | José de San Martín | ||||||||

| Historical era | 19th century | ||||||||

| July 28 1821 | |||||||||

| 1822 | |||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | PE | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Protectorate of Peru (Protectorado del Perú) was a protectorate created in 1821 in modern Peru after its declaration of independence. It existed for a year and 17 days, under the rule of José de San Martín and Argentina.

Peruvian War of Independence[]

The Peruvian War of Independence was composed of a series of military conflicts in Peru beginning with viceroy Abascal military reconquest in 1811 in the battle of Guaqui, going with the definitive defeat of the Spanish Army in 1824 in the battle of Ayacucho, and culminated in 1826, with the Siege of Callao.[1] The wars of independence took place with the background of the 1780–1781 uprising by indigenous leader Túpac Amaru II and the earlier removal of Upper Peru and the Río de la Plata regions from the Viceroyalty of Peru. Because of this the viceroy often had the support of the "Lima oligarchy," who saw their elite interests threatened by popular rebellion and were opposed to the new commercial class in Buenos Aires. During the first decade 1800s Peru had been a stronghold for royalists, who fought those in favor of independence in Perú, Upper Peru, Quito and Chile. Among the most important events during the war was the proclamation of independence of Peru by José de San Martín on July 28, 1821.

History[]

| History of Peru |

|---|

|

| By chronology |

| By political entity |

|

| By topic |

|

|

During the Peninsular War (1807–1814) central authority in the Spanish Empire was lost and many regions established autonomous juntas. The viceroy of Peru, José Fernando de Abascal y Sousa was instrumental in organizing armies to suppress uprisings in Upper Peru and defending the region from armies sent by the juntas of the Río de la Plata. After success of the royalist armies, Abascal annexed Upper Peru to the viceroyalty, which benefited the Lima merchants as trade from the silver-rich region was now directed to the Pacific. Because of this, Peru remained strongly royalist and participated in the political reforms implemented by the Cortes of Cádiz (1810–1814), despite Abascal's resistance. Peru was represented at the first session of the Cortes by seven deputies and local cabildos (representative bodies) became elected. Therefore, Peru became the second to last redoubt of the Spanish Monarchy in South America, after Upper Peru.[2] Peru eventually succumbed to patriot armies after the decisive continental campaigns of José de San Martín (1820–1823) and Simón Bolívar (1823–1825).

Some of the early Spanish conquistadors that explored Peru made the first attempts for independence from the Spanish crown. They tried to liberate themselves from the Viceroyalty, who governed for the king of Castile. Throughout the eighteenth century, there were several indigenous uprisings against colonial rule and their treatment by the colonial authorities. Some of these uprisings became true rebellions. The Bourbon Reforms increased the unease, and the dissent had its outbreak in the Rebellion of Túpac Amaru II which was repressed, but the root cause of the discontent of the indigenous people remained dormant. It is debated whether these movements should be considered as precedents of the emancipation that was led by chiefs (caudillos), Peruvian towns (pueblos), and other countries in the American continent.

The independence of Peru was an important chapter in the Hispano-American wars of independence. The campaign of Sucre in Upper Peru concluded in April 1825, and in November of the same year Mexico obtained the surrender of the Spanish bastion of San Juan de Ulúa in North America. The Spanish strongholds in Callao and Chiloé in South America fell in January 1826. Spain renounced all their continental American territories ten years later in 1836 leaving very little of its vast empire intact.

Junta movements[]

Despite the royalist tendencies of Peru, junta movements did emerge, often fomented by the approach of patriot armies from Buenos Aires. There were two short-lived uprisings in the southern city of Tacna in 1811 and 1813. One significant movement, led by Natives in Huánuco, began on February 22, 1812. It involved various leaders, including curacas and township magistrates (alcaldes pedáneos), but was suppressed within a few weeks. More enduring was the rebellion of Cuzco from 1814 to 1815.

The rebellion began in a confrontation between the Constitutional Cabildo and the Audiencia of Cuzco over the administration of the city. Cabildo officials and their allies were arrested by the Audiencia. Criollo leaders appealed to retired brigadier Mateo Pumacahua, who was curaca of Chinchero, and decades earlier had been instrumental in suppressing the rebellion of Túpac Amaru II. Pumacahua joined the Criollo leaders in forming a junta on August 3 in Cuzco, which demanded the complete implementation of the liberal reforms of the Spanish Constitution of 1812. After some victories in southern Peru and Upper Peru, the rebellion was squashed by mid-1815 when a combined strength of royal forces and loyal curacas, among which were the Catacora and Apo Cari took Cuzco and executed Pumacahua.[3]

Founding of the Peruvian Republic[]

This section may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: inconsistent use of tenses. (July 2013) |

José de San Martín and the Liberation Army of the South[]

After the squashing of the aforementioned rebellion, the Viceroy of Peru organised two expeditions; conformed by the royalist regiments of Lima and Arequipa, and expeditionary elements from Europe; against the Chilean Patriots. In 1814, the first expedition was successful in reconquering Chile after winning the Battle of Rancagua. In 1817 following the royalist defeat in the Battle of Chacabuco, the second expedition against the Chilean Patriots in 1818 was an attempt to restore the monarchy. Initially, it was successful in the Second Battle of Cancha Rayada, the expedition was finally defeated by José de San Martín in the Battle of Maipú.

To begin the liberation of Peru, Argentina and Chile signed a treaty on February 5, 1819, to prepare for the invasion. General José de San Martín believed that the liberation of Argentina wouldn't be secure until the royalist stronghold in Peru was defeated.[4]

Peruvian campaign[]

Following the Battle of Maipú and the subsequent liberation of Chile, the patriots began the preparations for an amphibious assault force to liberate Peru. Originally the costs were to be assumed by both Chile and Argentina, however the Chilean government under Bernardo O'Higgins ended up assuming most of costs of the campaign. Nonetheless, it was determined that the land army was to be commanded by José de San Martín, whilst the navy was to be commanded by admiral Thomas Alexander Cochrane.

The August 21, 1820, an amphibious landing took place in the city of Valparaiso by the Peruvian Liberation Expedition under Chilean flag. Said expedition was composed of 4,118 soldiers. On September 7 the Liberation expedition arrived on the bay of Pisco in today's Region of Ica and captured the province by the following day. In an attempt to negotiate, the viceroy of Peru sent a letter to José de San Martín September 15. However, negotiations broke down on October 14 with no clear result.

Beginning of hostilities[]

On October 9, 1820, the uprising of the reserve regiment of Grenadiers of Cusco began, which culminated in the proclamation of the Independence of Guayaquil. Then on October 21, General José de San Martín created the flag of Republic of Peru.

Actual hostilities began with the 1st Campaign of Arenales in the Peruvian highlands led by patriot General Juan Antonio Álvarez de Arenales between October 4, 1820, to January 8, 1821, he reunited with General San Martín in Huaura. During this campaign, General Arenales proclaimed the independence of the city of Huamanga (Ayacucho) on November 1, 1820. This was followed by the Battle of Cerro de Pasco, where General Arenales defeated a royalist division sent by viceroy Pezuela. The rest of the liberation forces under Admiral Cochrane captured the royalist frigate Esmeralda on November 9, 1820, dealing the royalist navy a heavy blow. Moreover, on December 2, 1820, the royalist battalion Batallón Voltígeros de la Guardia defected to the patriots' side. During January 8, 1821, the armed column of General Álvarez de Arenales reunites with the rest of the expedition in the coast.

Viceroy Pezuela was ousted and replaced by General José de la Serna on January 29, 1821. In March 1821, incursions led by Miller and Cochrane attacked the royalist ports of Arica and Tacna. The new viceroy announced his departure from Lima on June 5, 1821, but ordered a garrison to resist the patriots in the Real Felipe Fortress, leading to the First Siege of Callao. The royalist army under the command of General José de Canterac leaves Lima, and proceeded to the highlands on June 25, 1821. General Arenales was sent by General San Martín to observe the royalist retreat. Two days after, the Liberation Expedition entered Lima. Under fear of repression and pillaging, the inhabitants of Lima begged General San Martín to enter Lima.

Declaration of independence[]

Once inside Lima, General San Martín invited all of the populace of Lima to swear oath to the independence cause. The signing of the Act of Independence of Peru was on July 15, 1821. , later Minister of International Relations wrote the Act of Independence. Admiral Cochrane is welcomed in Lima two days later; General José de San Martín announces in the Plaza Mayor of Lima the famous declaration of independence:

DESDE ESTE MOMENTO EL PERÚ ES LIBRE E INDEPENDIENTE POR LA VOLUNTAD GENERAL DE LOS PUEBLOS Y POR LA JUSTICIA DE SU CAUSA QUE DIOS DEFIENDE. ¡VIVA LA PATRIA!, ¡VIVA LA LIBERTAD!, ¡VIVA LA INDEPENDENCIA!.

— José de San Martín. Lima, 28th of July of 1821

San Martín Abandons Peru[]

José de la Serna, moves his headquarters to Cuzco (or Qosqo), and attempts to help the beleaguered royalist forces in Callao. He sends troops under the command of General Canterac which arrive in Lima September 10, 1821. He is successful in reuniting with the besieged forces of General José de La Mar, in the Fortress of Real Felipe. After learning the viceroy new orders, he leaves to the highlands again on September 16 of the same year. The republicans pursued the retreating royalists until reaching Jauja on October 1, 1821.

Antonio José de Sucre, in Guayaquil requests help from San Martín. He complies and leads the Auxiliary Expedition of Santa Cruz to Quito. Afterwards, during the Entrevista de Guayaquil, San Martín and Bolívar attempted to decide the political fate of Peru. San Martín opted for a Constitutional Monarchy, whilst Simon Bolivar (Head of the Northern Expedition) opted for a Republican. Nonetheless, they both followed the notion that it was to be independent of Spain. Following the interview, General San Martin abandons Peru September 22, 1822, and leaves whole command of the Independence movement to Simon Bolivar.

After a row with General San Martin, Admiral Cochrane leaves Peru on May 10, 1822, being replaced by Martin Guisse as head of the navy. In April 1822, a royalist incursion defeats a Republican Army in the . Afterwards, in October 1822 the republicans under General Rudecindo Alvarado experience another costly defeat at the hands of the royalist.

Simón Bolívar, the Northern Expedition, and the end of colonial era[]

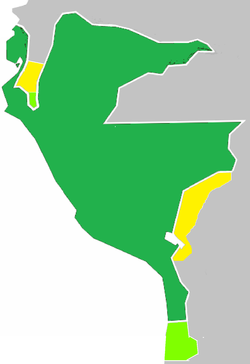

Following the declaration of Independence, the Peruvian state was bogged down by the royalist resistance, and instability of the republic itself. Hence, whilst the coast and Northern Peru was under the command of the republic, the rest of the country was under the control of the royalists. Viceroy La Serna had established his capital in the city of Cuzco. Another campaign under General Santa Cruz against the royalist is defeated. The end of the war would only come with the military intervention of Gran Colombia. Following the self exile of San Martin, and the constant military defeats under president José de la Riva Agüero, the congress decided to send a plea in 1823 for the help of Simón Bolívar. Bolivar arrived in Lima December 10, 1823, with the aims of liberating all of Peru.

In 1824, an uprising in the royalist camp in Alto Peru (Modern Bolivia), would pave the way for the battles of Junin and Ayacucho. The Peruvian Army triumphed in the battle of Junin under the personal orders of Simon Bolivar, and in the battle of Ayacucho under command of General Antonio José de Sucre. The war would not end until the last royalist holdouts surrendered the Real Felipe Fortress in 1826.

Aftermath[]

Political dependence on Spain had been severed, but Peru was still economically dependent on Europe. Despite the separation from Spain, the plunder of lands from indigenous people was exacerbated in this new republican era. Indigenous domestic servants were treated inhumanely all the way into the 20th century. During the birth of the republic, the indigenous people obtained open citizenship in Peru, August 27, 1821. Still amid the 21st century, a truly democratic society is still being constructed where the full guarantee and respect for human rights is possible.[citation needed]

After the war of independence, conflicts of interests that faced different sectors of the Criollo society and the particular ambitions of individual caudillos, made the organization of the country excessively difficult. Only three civilians: Manuel Pardo, Nicolás de Piérola and Francisco García Calderón would accede to the presidency in the first seventy-five years of independent life. In 1837, the Peru-Bolivian Confederation was created but it was dissolved two years later due to a combined military intervention of Peruvian patriots and the Chilean military.[citation needed]

References[]

- ^ [Armies, Politics and Revolution: Chile, 1808–1826|https://books.google.es/books?id=WhPxDQAAQBAJ&lpg=PA218&ots=Ov5_Qh-6C5&dq=Siege%20of%20callao%201826&hl=es&pg=PA218#v=onepage&q&f=false]

- ^ Lynch, John (1986). The Spanish American Revolutions 1808–1826 (2 ed.). London: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 164–165. ISBN 0-393-95537-0.

- ^ Lynch, Spanish American Revolutions, 165–170.

- ^ "Aniversario de la Proclamacion de la Independencia del Perú" (PDF) (in Spanish). Archived from the original (pdf) on December 13, 2011. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- Former countries in South America

- Former unrecognized countries

- Peruvian War of Independence

- 1821 establishments in Peru

- 1822 disestablishments in South America