Pseudolaw

Pseudolaw consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that are claimed to be based on accepted law or legal doctrine, but which deviate significantly from most conventional understandings of law and jurisprudence, or which originate from non-existent statutes or legal principles the advocate or adherent incorrectly believes exist.[1] Donald Netolitzky defined it as "a collection of legal-sounding but false rules that purport to be law",[2] a definition that distinguishes pseudolaw from arguments that fail to conform to existing laws such as novel arguments or a ignorance of precedent in case law.[3][4] The features are distinct and conserved.[3] It is sometimes referred to as "legalistic gibberish".[5] The more extreme examples have been classified as paper terrorism.

Followers of such ideologies can cause problems for courts and government administrators by filing unusual applications that are difficult to process. Courts in Canada refer to such arguments as organized pseudolegal commercial arguments (OPCA), and have called them frivolous and vexatious.[6] There is no recorded instance of such tactics being upheld in a court of law.[7] Pseudolaw belief can resemble mental illness.[3][8]

Common among pseudolegal beliefs is a belief that one possesses partial or full sovereignty independent from the government of the country in which they live, and a belief that no laws, or only certain laws, apply to the believer. Groups espousing such pseudolegal beliefs include freemen on the land and the sovereign citizen movement. Some, such as the Reichsbürgerbewegung ("Reich Citizens' Movement") groups in Germany, believe that their state itself is illegitimate.

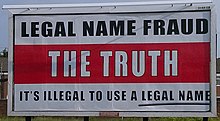

Also under the umbrella of pseudolegal arguments are conspiracy theorists who believe there is a secret parallel legal system that one can access through certain means, like using a secret phrase or by placing stamps on the right place on documents. For example, the redemption movement believes that a secret fund is created for everyone at birth by the government, and that a procedure exists to "redeem" or reclaim money from this fund. See tax protester conspiracy arguments for a discussion of these beliefs related to tax law. Many of these revolve around the "legal name fraud" movement, which believes that birth certificates give the state legal ownership of a personal name and refusing to use this name therefore removes oneself from a court's jurisdiction.[9][10] Various groups advocate that one can avoid this state ownership by distinguishing between capitalized and non-capitalized versions of one's name, or by adding punctuation to one's name. See strawman theory (also known as the capital letters argument) for more information.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some business owners and individuals cited pseudolaw, such as obsolete clauses in the Magna Carta, to attempt to escape coronavirus restrictions.[11][12]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ McRoberts, Colin (March 21, 2016). "Here comes pseudolaw, a weird little cousin of pseudoscience". Aeon. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Netolitzky, Donald (2018). "A Rebellion of Furious Paper: Pseudolaw As a Revolutionary Legal System". SSRN Electronic Journal. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3177484. ISSN 1556-5068.

- ^ a b c Donald Netolitzky (August 23, 2018), "Lawyers and Court Representation of Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Argument [OPCA] Litigants in Canada", UBC Law Review, 51 (2), pp. 419–488, SSRN 3237255, retrieved 2020-06-23

- ^ Colin McRoberts (June 6, 2019), "Tinfoil Hats and Powdered Wigs: Thoughts on Pseudolaw", Washburn Law Journal, 58 (3, 2019), pp. 637–668, SSRN 3400362, retrieved 2020-06-23

- ^ "T.C. Memo. 2000-11" (PDF). ustaxcourt.gov. U.S. Tax Court. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Meads v. Meads, 2012 ABQB 571(CanLII), Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta, 18 September 2012, para. 77

- ^ Bizzle, Legal (18 November 2011). "The freeman-on-the-land strategy is no magic bullet for debt problems". The Guardian.

- ^ Pytyck, Jennifer; Chaimowitz, Gary A. (2013). "The Sovereign Citizen Movement and Fitness to Stand Trial". International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 12 (2): 149–153. doi:10.1080/14999013.2013.796329. ISSN 1499-9013. S2CID 144117045.

- ^ Dalgleish, Katherine. "Guns, border guards, and the Magna Carta: the Freemen-on-the-Land are back in Alberta courts". lexology.com. Lexology. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Kelly, John (June 11, 2016). "The mystery of the 'legal name fraud' billboards". BBC News. Retrieved January 4, 2018.

- ^ Coleman, Alistair, "Covid lockdown: Why Magna Carta won't exempt you from the rules", Reality Check, BBC, retrieved March 8, 2021

- ^ https://nationalpost.com/news/alberta-judge-bars-new-pseudo-law-advocate-who-claims-magna-carta-puts-her-outside-courts-authority[bare URL]

- Fringe theories

- Theories of law

- Pseudolaw