Sovereign citizen movement

The sovereign citizen movement is a loose grouping of primarily American litigants, commentators, tax protesters, and financial-scheme promoters, who see themselves as answerable only to their particular interpretations of the common law and as not subject to any government statutes or proceedings.[1] In the United States, they do not recognize U.S. currency and maintain that they are "free of any legal constraints".[2][3][4] They especially reject most forms of taxation as illegitimate.[5] Participants in the movement argue this concept in opposition to the idea of "federal citizens", who, they say, have unknowingly forfeited their rights by accepting some aspect of federal law.[6] The doctrines of the movement resemble those of the freemen on the land movement more commonly found in the British Commonwealth, such as Australia and Canada.[7][8][9][10]

Many members of the sovereign citizen movement believe that the United States government is illegitimate.[11] The sovereign citizen movement has been described as consisting of individuals who believe that the county sheriff is the most powerful law-enforcement officer in the country, with authority superior to that of any federal agent, elected official, or local law-enforcement official.[12] The movement can be traced back to white-extremist groups like Posse Comitatus and the constitutional militia movement.[13] It also includes members of certain self-declared "Moorish" sects.[14]

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) classifies some sovereign citizens ("sovereign citizen extremists") as domestic terrorists.[15] In 2010, the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) estimated that approximately 100,000 Americans were "hard-core sovereign believers", with another 200,000 "just starting out by testing sovereign techniques for resisting everything from speeding tickets to drug charges".[16]

In surveys conducted in 2014 and 2015, representatives of U.S. law enforcement ranked the risk of terrorism from the sovereign citizen movement higher than the risk from any other group, including Islamic extremists, militias, racists, and neo-Nazis.[17][18] The New South Wales Police Force in Australia has also identified sovereign citizens as a potential terrorist threat.[19]

Theories

The movement is not unified, but there are common themes. A number of leaders, referred to as "gurus", develop their own variations.[20]

Sovereign legal theories reinterpret the Constitution of the United States through selective reading of law dictionaries, state court opinions, or specific capitalization, and incorporate other details from a variety of sources not limited to the Uniform Commercial Code, the Articles of Confederation, the Magna Carta, the Bible, and foreign treaties. They ignore the second clause of Article VI of the Constitution (the Supremacy Clause), which establishes the Constitution as the law of the land and the United States Supreme Court as the ultimate authority to interpret it.[21][22]

Writing in American Scientific Affiliation, Dennis L. Feucht reviewed American Militias: Rebellion, Racism & Religion by Richard Abanes, and described the theory of Richard McDonald, a sovereign-citizen leader, which is that there are two classes of citizens in America: the "original citizens of the states" (or "States citizens") and "U.S. citizens". McDonald asserts that U.S. citizens or "Fourteenth Amendment" citizens have civil rights, legislated to give the freed black slaves after the Civil War rights comparable to the unalienable constitutional rights of white state citizens. The benefits of U.S. citizenship are received by consent in exchange for freedom. State citizens consequently take steps to revoke and rescind their U.S. citizenship and reassert their de jure common-law state citizen status. This involves removing one's self from federal jurisdiction and relinquishing any evidence of consent to U.S. citizenship, such as a Social Security number, driver's license, car registration, use of ZIP codes, marriage license, voter registration, and birth certificate. Also included is refusal to pay state and federal income taxes because citizens not under U.S. jurisdiction are not required to pay them. Only residents (resident aliens) of the states, not its citizens, are income-taxable, state citizens argue. And as a state citizen landowner, one can bring forward the original land patent and file it with the county for absolute or allodial property rights. Such allodial ownership is held "without recognizing any superior to whom any duty is due on account thereof" (Black's Law Dictionary). Superiors include those who levy property taxes or who hold mortgages or liens against the property.[23]

The unpassed Titles of Nobility Amendment has been invoked to challenge the legitimacy of the courts as lawyers sometimes use the informal title of Esquire.[24]

In support of his theories, McDonald has established State Citizen Service Centers around the United States as well as a related web presence.[25]

Writer Richard Abanes asserts that sovereign citizens fail to sufficiently examine the context of the case laws they cite, and ignore adverse evidence, such as Federalist No. 15, wherein Alexander Hamilton expressed the view that the Constitution placed everyone personally under federal authority.[23]

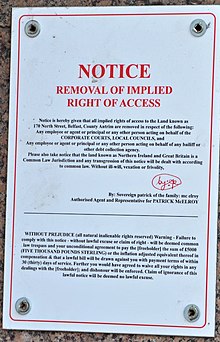

They may apply thumbprints to documents to distinguish "flesh and blood" people from a fictitious strawman entity that is subject to the government.[13] Signatures and thumbprints are likely to be in red ink or blood, and black and blue inks are believed to indicate corporations.[26]

Some sovereign citizens also claim that they can become immune to most or all laws of the United States by renouncing their citizenship, a process they refer to as "expatriation", which involves filing or delivering a nonlegal document claiming to renounce citizenship in a "federal corporation" and declaring only to be a citizen of the state in which they reside, to any county clerk's office that can be convinced to accept it.[27] Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, courts were slowed down by a number of defendants who changed their names and declared affiliation with the "Moorish Nation", claiming that they are not culpable for acts committed under the old name and are immune to prosecution because of the affiliation.[28] Other beliefs include the idea that people can be tricked into a contract of adhesion that binds them to the government by using various things including Social Security numbers, fishing licenses, or ZIP Codes and that avoiding their use means immunity from government authority.[29][30] Using arguments that rely on exacting definitions and word choice, sovereign citizens may assert a "right to travel" in a "conveyance", distinguishing it from driving an automobile to justify ignoring requirements for license plates, vehicle registration, and driver's licenses. The right to travel is claimed based on a variety of passages, some being more commonly used among groups.[21]

History

The concept of a sovereign citizen originated in 1971 in the Posse Comitatus movement as a teaching of Christian Identity minister William P. Gale. The concept has influenced the tax protester movement, the Christian Patriot movement, and the redemption movement—the last of which claims that the U.S. government uses its citizens as collateral against foreign debt.[6] The 1980s farm crisis saw the rise of anti-government protesters selling fraudulent debt-relief programs.[31]

Gale identified the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution as the act that converted "sovereign citizens" into "federal citizens" by their agreement to a contract to accept benefits from the federal government. Other commentators have identified other acts, including the Uniform Commercial Code, the Emergency Banking Act,[32] the Zone Improvement Plan,[33] and the alleged suppression of the Titles of Nobility Amendment.[34]

In addition to Gale's white-nationalist origins, their sovereign arguments have been adopted by the Moorish sovereigns. Their beliefs may have derived, in part, from the Moorish Science Temple of America, which has condemned the sovereign citizen ideologies. The underpinnings of the theories of African-American exemption vary. The Washitaw Nation claims rights through provisions in the Louisiana Purchase treaty granting privileges to Moors as early colonists and the non-existent "United Nations Indigenous People’s Seat 215".[14] Sovereign citizen ideas have been adopted by some groups within the Hawaiian sovereignty movement.[1]

Other than common conspiracy theories about legitimate government having been usurped and replaced, there is no defining text, goals or leadership to the movement.[35] Some of those in the movement believe that the term "sovereign citizen" is an oxymoron and prefer to label themselves as individuals "seeking the Truth".[36]

A sovereign citizen group known as the Oath Enforcers attracted QAnon and Donald Trump supporters into the movement following the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol.[37]

Legal status of theories

Individuals have tried to use "sovereign citizen" arguments in U.S. federal tax cases since the 1970s. Variations of the argument that an individual is not subject to various laws because the individual is "sovereign" have been rejected by the courts, especially in tax cases such as Johnson v. Commissioner (Phyllis Johnson's argument—that she was not subject to the federal income tax because she was an "individual sovereign citizen"—was rejected by the court),[38] Wikoff v. Commissioner (argument by Austin Wikoff—that he was not subject to the federal income tax because he was an "individual sovereign citizen"—was rejected by the court),[39] United States v. Hart (Douglas Hart's argument—in response to a lawsuit against him for filing false lien notices against Internal Revenue Service personnel, that the U.S. District Court had no jurisdiction over him because he was a "sovereign citizen"—was rejected by the District Court and the United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit),[40] Young v. Internal Revenue Service (Jerry Young's argument—that the Internal Revenue Code did not pertain to him because he was a "sovereign citizen"—was rejected by the U.S. District Court),[41] and Stoecklin v. Commissioner (Kenneth Stoecklin's argument—that he was a "freeborn and sovereign" person and was therefore not subject to the income tax laws—was rejected by the United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit; the court imposed a $3,000 penalty on Stoecklin for filing a frivolous appeal).[42] See also Missett v. Commissioner[43] and Hyslep v. Commissioner.[44]

In Risner v. Commissioner, Gregg Risner's argument—that he was not subject to federal income tax because he was a "Self-governing Free Born Sovereign Citizen"—was rejected by the court as being a "frivolous protest" of the tax laws.[45] See also Maxwell v. Snow (Lawrence Maxwell's arguments—that he was not subject to U.S. federal law because he was a "sovereign citizen of the Union State of Texas", that the United States was not a republican form of government and therefore must be abolished as unconstitutional, that the Secretary of the Treasury's jurisdiction was limited to the District of Columbia, and that he was not a citizen of the United States—were rejected by the court as being frivolous),[46] and Rowe v. Internal Revenue Service (Heather Rowe's arguments — that she was not subject to federal income tax because she was not a "party to any social compact or contract", because the IRS had no jurisdiction over her or her property, because she was "not found within the territorial limited jurisdiction of the US", because she was a "sovereign Citizen of the State of Maine", and because she was "not a U.S. Citizen as described in 26 U.S.C. 865(g)(1)(A) . . ."—were rejected by the court and were ruled to be frivolous).[47]

Other tax cases include Heitman v. Idaho State Tax Commission,[48] Cobin v. Commissioner (John Cobin's arguments—that he had the ability to opt out of liability for federal income tax because he was white, that he was a "sovereign citizen of Oregon", that he was a "non-resident alien of the United States", and that his sovereign status made his body real property—were rejected by the court and were ruled to be "frivolous tax-protester type arguments"),[49] Glavin v. United States (John Glavin's argument—that he was not subject to an IRS summons because, as a sovereign citizen, he was not a citizen of the United States—was rejected by the court),[50] and United States v. Greenstreet (Gale Greenstreet's arguments—that he was of "Freeman Character" and "of the White Preamble Citizenship and not one of the 14th Amendment legislated enfranchised De Facto colored races", that he was a "white Preamble natural sovereign Common Law De Jure Citizen of the Republic/State of Texas", and that he was a sovereign, not subject to the jurisdiction of the United States District Court—were ruled to be "entirely frivolous").[51] In view of such cases, the IRS has added "free born" or "sovereign" citizenship to its list of frivolous claims that may result in a $5,000 penalty when used as the basis for an inaccurate tax return.[52]

Similarly, when Andrew Schneider was convicted and sentenced to five years in prison for making a threat by mail, Schneider argued that he was a free, sovereign citizen and therefore was not subject to the jurisdiction of the federal courts. That argument was rejected by the United States Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit as having "no conceivable validity in American law".[53]

In a criminal case in 2013, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington noted:

Defendant [Kenneth Wayne Leaming] is apparently a member of a group loosely styled "sovereign citizens". The Court has deduced this from a number of Defendant's peculiar habits. First, like Mr. Leaming, sovereign citizens are fascinated by capitalization. They appear to believe that capitalizing names have some sort of legal effect. For example, Defendant writes that "the REGISTERED FACTS appearing in the above Paragraph evidence the uncontroverted and uncontrovertible FACTS that the SLAVERY SYSTEMS operated in the names UNITED STATES, United States, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, and United States of America ... are terminated nunc pro tunc by public policy, U.C.C. 1-103 ..." (Def.'s Mandatory Jud. Not. at 2.) He appears to believe that by capitalizing "United States", he is referring to a different entity than the federal government. For better or for worse, it's the same country.

Second, sovereign citizens, like Mr. Leaming, love grandiose legalese. "COMES NOW, Kenneth Wayne, born free to the family Leaming, [date of birth redacted], constituent to The People of the State of Washington constituted 1878 and admitted to the union 22 February 1889 by Act of Congress, a Man, "State of Body" competent to be a witness and having First Hand Knowledge of The FACTS ..." (Def.'s Mandatory Jud. Not. at 1.)

Third, Defendant evinces, like all sovereign citizens, a belief that the federal government is not real and that he does not have to follow the law. Thus, Defendant argues that as a result of the "REGISTERED FACTS", the "states of body, persons, actors and other parties perpetuating the above-captioned transaction(s) [i.e., the Court and prosecutors] are engaged ... in acts of TREASON, and if unknowingly as victims of TREASON and FRAUD ..." (Def.'s Mandatory Jud. Not. at 2.)

The Court, therefore, feels some measure of responsibility to inform Defendant that all the fancy legal-sounding things he has read on the internet are make-believe ...[54]

Defendant Kenneth Wayne Leaming was found guilty of three counts of retaliating against a federal judge or law enforcement officer by a false claim, one count of concealing a person from arrest, and one count of being a felon in possession of a firearm.[55] On May 24, 2013, Leaming was sentenced to eight years in federal prison.[56]

In Australia there have been a few minor cases where parties have invoked arguments surrounding the "sovereign man".[57] All of these arguments have failed before Australian courts. The courts in New Zealand also appear to have rejected the "sovereign man" arguments.[58]

Filing of false lien notices

According to The New York Times, cases involving so-called sovereign citizens pose "a challenge to law enforcement officers and court officials" in connection with the filing of false notices of liens—a tactic sometimes called "paper terrorism". Anyone can file a notice of lien against property such as real estate, vehicles, or other assets of another under the Uniform Commercial Code and other laws. In most states of the United States, the validity of liens is not investigated or inquired into at the time of filing. Notices of liens (whether legally valid or not) are a cloud on the title of the property and may affect the property owner's credit rating, ability to obtain home equity loans, refinance the property or take other action with regards to the property. Notices of releases of liens generally must be filed before property may be transferred. The validity of a lien is determined by further legal procedures. Clearing up fraudulent notices of liens may be expensive and time-consuming. Filing fraudulent notices of liens or documents is both a crime and a civil offense.[13]

U.S. government responses

Following the 1995 Oklahoma City bombing, Congress passed the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, enhancing sentences for certain terrorist-related offenses.[59]

In October 2015, during a domestic terrorism seminar at George Washington University, National Security Division leader and Assistant Attorney General, John P. Carlin, stated that the Obama Administration had witnessed "anti-government views triggering violence throughout America". Carlin personally confirmed the 2014 START survey findings, saying that during his time at the FBI and DOJ, law enforcement officials had identified sovereign citizens as their top concern. Carlin referred to social media as a "radicalization echo chamber", through which domestic extremists deliver, re-appropriate and reinforce messages of hate, propaganda, and calls to recruitment and violence. He charged its service providers with the responsibility of tracking and taking action against, any such abuse of its services.[60]

Similar groups outside the United States

There is some cross-over between the two groups which call themselves Freemen and Sovereign Citizens, as well as various others sharing similar beliefs.[61]

English-speaking countries

With the advent of the Internet and continuing during the 21st century, people throughout the English-speaking world who share the core beliefs of these movements (which may be loosely defined as "see[ing] the state as a corporation with no authority over free citizens") have been able to connect and share their beliefs. There are now followers in the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand.[61] While arguments specific to the history and laws of the United States are not used, many concepts have been incorporated or adapted by individuals and groups in English-speaking countries of the British Commonwealth: Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand.[62][61] Sovereign Citizens from the US have gone on speaking tours to New Zealand and Australia, appealing to farmers struggling with drought, and there are Internet presences in both countries.[61]

Australia

In Australia, there is some cross-over between groups which call themselves Freemen on the Land (FOTL)[63] and sovereign citizens (and some others), but both have their roots in the American farm crisis and the US/Canadian financial crisis of the 1980s.[61][63] There have been several court cases testing the core concept, none successful for the "freemen".[64] In 2011, climate denier and political activist Malcolm Roberts (later elected senator for Pauline Hanson's One Nation party), wrote a letter to then Prime Minister Julia Gillard filled with characteristic sovereign citizen ideas, although he denied that he was a "sovereign citizen".[65][66]

From the 2010s, there has been a growing number of freemen targeting Indigenous Australians, with groups with names like Tribal Sovereign Parliament of Gondwana Land, the Original Sovereign Tribal Federation (OSTF)[67] and the Original Sovereign Confederation. OSTF Founder Mark McMurtrie, an Aboriginal Australian man, has produced YouTube videos speaking about “common law”, which incorporate Freemen beliefs. Appealing to other Aboriginal people by partly identifying with the land rights movement, McMurtrie played on their feelings of alienation and lack of trust in the systems which had not served Indigenous people well.[68]

In 2015, the New South Wales Police Force identified "sovereign citizens" as a potential terrorist threat, estimating that there were about 300 sovereign citizens in the state at the time.[69] Sovereign citizens from the US have undertaken speaking tours to New Zealand and Australia, with some support among farmers struggling with drought and other hardships. A group called United Rights Australia (U R Australia)[70] has a Facebook presence, and there are other websites promulgating Freemen/Sovereign Citizen ideas.[61][71]

Canada

Canada had an estimated 30,000 sovereign citizens in 2015, many associating with the freemen on the land movement.[72] A ruling from the Court of Queen's Bench of Alberta examined almost 150 cases involving pseudolaw, grouping them and characterizing them as "Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Arguments".[73]

Austria and Germany

Groups with similar behaviors are found in Austria and Germany. The Reichsbürger movement (Reichsbürger, Reich citizen) in Germany originated around 1985 and had approximately 19,000 members in 2019, more concentrated in the south and east. The originator claimed to have been appointed head of the post-World War I Reich, but other leaders claim imperial authority. The movement consists of different, usually small groups. Groups have issued passports and identification cards.[74][75]

In Austria, the group Staatenbund Österreich (Austrian Commonwealth), in addition to issuing its own passports and licence plates, had a written constitution.[76] The group, established in November 2015, used language from a United States-based sovereign citizen group, "One People's Public Trust".[77] Its leader was sentenced to 14 years in jail after trying to order the Austrian Armed Forces to overthrow the government and requesting foreign assistance from Vladimir Putin; other members received lesser sentences.[78]

See also

Incidents

- 1995 Oklahoma City bombing

- 2003 standoff in Abbeville, South Carolina

- 2010 West Memphis police shootings

- 2014 Bundy standoff

- 2016 Occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge

- 2016 shooting of Baton Rouge police officers

- 2018 Nashville Waffle House shooting

- 2021 Wakefield, Massachusetts standoff

Groups

- Embassy of Heaven

- Guardians of the Free Republics

- Militia organizations in the United States

- Moorish Sovereign Citizens

- Patriot movement

Individuals

- Edward and Elaine Brown[15]

- Schaeffer Cox[79]

- Jared Fogle[80]

- John Joe Gray[81]

- Richard Marple[82]

- Glenn Unger[83]

Concepts

- Anarcho-capitalism

- Antinomianism

- Declarationism

- Eumeswil

- Self-ownership

- Social contract

- Strawman theory

- Tax resistance in the United States

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b Laird, Lorelei (May 1, 2014), "'Sovereign citizens' plaster courts with bogus legal filings--and some turn to violence", ABA Journal, archived from the original on November 2, 2014, retrieved June 22, 2020

- ^ Yerak, Becky; Sachdev, Ameet (June 11, 2011). "Giordano's strange journey in bankruptcy". Chicago Tribune.

- ^ Also, see generally Johnson, Kevin (March 30, 2012). "Anti-government 'Sovereign Movement' on the rise in U.S." USA Today. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved September 14, 2017.

- ^ "'Sovereign Citizen' Suing State Arrested Over Traffic Stop". WRTV. April 6, 2012. Archived from the original on April 10, 2012. Retrieved April 8, 2012.

- ^ The Sovereign Citizen Movement Archived January 13, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. The Militia Watchdog Archives. Anti-Defamation League.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Carey, Kevin (July 2008). "Too Weird for The Wire". Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved July 19, 2008.

- ^ Graveland, Bill. "Freemen-On-The-Land: Little-Known 'Sovereign Citizen' Movement Emerged From Shadows In 2013". HuffPost. The Canadian Press. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ Wagner, Adam. "Freemen on the Land are 'parasites' peddling 'pseudolegal nonsense': Canadian judge fights back". UK Human Rights Blog. 1 Crown Office Row barristers' chambers. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ Rush, Curtis. "Sovereign citizen movement: OPP is watching". Toronto Star. Archived from the original on June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ "The Law Society of British Columbia: Practice Tips: The Freeman-on-the-Land movement". Archived from the original on April 17, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2015.

- ^ "Context Matters: the Cliven Bundy Standoff". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 2, 2014. Retrieved May 2, 2014.

- ^ MacNab, JJ. "Context Matters: The Cliven Bundy Standoff -- Part 3". Forbes. Archived from the original on May 7, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Goode, Erica (August 23, 2013). "In Paper War, Flood of Liens Is the Weapon". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved August 24, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Moorish Sovereign Citizens, Southern Poverty Law Center, archived from the original on July 11, 2019, retrieved July 11, 2019

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sovereign Citizens A Growing Domestic Threat to Law Enforcement". Domestic Terrorism. Federal Bureau of Investigation. September 1, 2011. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved May 3, 2015.

- ^ MacNab, J.J. "'Sovereign' Citizen Kane" Archived January 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Intelligence Report. Issue 139. Southern Poverty Law Center. Fall 2010.

- ^ Rivinius, Jessica (July 30, 2014). "Sovereign citizen movement perceived as top terrorist threat". National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism. Archived from the original on August 6, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ "David Carter, Steve Chermak, Jeremy Carter & Jack Drew, "Understanding Law Enforcement Intelligence Processes: Report to the Office of University Programs, Science and Technology Directorate, U.S. Department of Homeland Security," July 2014, National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (College Park, Maryland)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on August 9, 2014. Retrieved August 7, 2014.

- ^ Thomas, James; McGregor, Jeanavive (November 30, 2015). "Sovereign citizens: Terrorism assessment warns of rising threat from anti-government extremists". ABC News. Archived from the original on November 30, 2015. Retrieved November 30, 2015.

- ^ The Lawless Ones: The Resurgence of the Sovereign Citizen Movement (PDF) (2nd ed.), Anti-Defamation League, 2012, retrieved June 19, 2020

- ^ Jump up to: a b Kalinowski, Caesar IV (August 1, 2019), "A Legal Response to the Sovereign Citizen Movement", Montana Law Review, 80 (2): 153–210, retrieved May 1, 2020

- ^ "Sovereign Citizens: A Growing Domestic Threat to Law Enforcement", FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin, September 1, 2011, retrieved May 5, 2020

- ^ Jump up to: a b Feucht, Dennis (June 1997). "Essay Review of AMERICAN MILITIAS: Rebellion, Racism & Religion". Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith. American Scientific Affiliation. pp. 116–118. Archived from the original on September 23, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2014.

- ^ Parker, George F. (September 2014), "Competence to Stand Trial Evaluations of Sovereign Citizens: A Case Series and Primer of Odd Political and Legal Beliefs", Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online, 42 (3), pp. 338–349, PMID 25187287, retrieved April 30, 2020

- ^ "Welcome to the State Citizen's Service Center". April 18, 2015. Archived from the original on March 26, 2014. Retrieved April 18, 2015.

- ^ Williams, Jennifer (February 9, 2016), "Why some far-right extremists think red ink can force the government to give them millions", Vox, retrieved August 18, 2020

- ^ Morton, Tom (April 17, 2011). "Sovereign citizens renounce first sentence of 14th Amendment". Casper Star-Tribune. Archived from the original on January 21, 2016. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- ^ 'Moorish Defense' Slowing Court Cases In Mecklenburg, WSOC-TV, July 19, 2011, retrieved April 30, 2020

- ^ Knight, Peter (2003). Conspiracy Theories in American History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-57607-812-9.

- ^ Valeri, Robin Maria; Borgeson, Kevin (May 11, 2018). Terrorism in America. Taylor & Francis. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-315-45599-0.

- ^ Miller, Joshua Rhett (January 5, 2014), Sovereign citizen movement rejects gov't with tactics ranging from mischief to violence, Fox News, retrieved June 22, 2020

- ^ Hall, Kermit; Clark, David Scott (2002). The Oxford Companion to American Law.

- ^ Fleishman, David (Spring 2004). "Paper Terrorism: The Impact of the 'Sovereign Citizen' on Local Government". The Public Law Journal. 27 (2).

- ^ Smith, William C. (November 1996). "The Law According to Barefoot Bob". ABA Journal.

- ^ Huffman, John Pearley (January 6, 2020). "Sovereign Citizens Take Their Anti-Government Philosophy to the Roads". Car and Driver. Archived from the original on January 6, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ^ MacNab, J.J. (February 13, 2012). "What is a Sovereign Citizen?". Forbes. Archived from the original on July 29, 2017.

- ^ "How the far-right group 'Oath Enforcers' plans to harass political enemies". the Guardian. April 6, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2021.

- ^ "37 T.C.M. (CCH) 189, T.C. Memo 1978-32 (1978)".

- ^ "37 T.C.M. (CCH) 1539, T.C. Memo 1978-372 (1978)".

- ^ 701 F.2d 749 (8th Cir. 1983) (per curiam)

- ^ "596 F. Supp. 141 (N.D. Ind. 1984)".

- ^ "865 F.2d 1221 (11th Cir. 1989)".

- ^ 49 T.C.M. (CCH) 602, T.C. Memo 1985-42 (1985).

- ^ 55 T.C.M. (CCH) 1203, T.C. Memo 1988-289 (1988).

- ^ "Docket # 18494-95, 71 T.C.M. (CCH) 2210, T.C. Memo 1996-82, United States Tax Court (February 26, 1996)".

- ^ "409 F.3d 354 (D.C. Cir. 2005)".

- ^ "Case no. 06-27-P-S, U.S. District Court for the District of Maine (May 9, 2006)".

- ^ Case no. CV-07-209-E-BLW, U.S. District Court for the District of Idaho (June 29, 2007).

- ^ "Docket # 16905-05L, T.C. Memo 2009–88, United States Tax Court (April 28, 2009)".

- ^ "Case no. 10-MC-6-SLC, U.S. District Court for the Western District of Wisconsin (June 4, 2010)".

- ^ "912 F.Supp. 224 (N.D. Tex. 1996)".

- ^ "The Truth about Frivolous Tax Arguments" Archived March 21, 2014, at the Wayback Machine. Internal Revenue Service. January 1, 2011.

- ^ "United States v. Schneider, 910 F.2d 1569 (7th Cir. 1990)".

- ^ Order, docket entry 102, Feb. 12, 2013, United States v. Kenneth Wayne Leaming, case no. 12-cr-5039-RBL, U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington.

- ^ Jury verdicts, February 28, 2013 and March 1, 2013, United States v. Kenneth Wayne Leaming, case no. 12-cr-5039-RBL, U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington.

- ^ News release, May 24, 2013, Office of the United States Attorney for the Western District of Washington Archived July 14, 2013, at the Wayback Machine Leaming is incarcerated at the United States Penitentiary at Marion, Illinois, and is scheduled for release on July 12, 2019. See Federal Bureau of Prisons record, Kenneth Wayne Leaming, inmate # 34928-086, U.S. Dep't of Justice.

- ^ Agapis v Birmingham DCJ [2013] WASC 329, Supreme Court (WA, Australia).

- ^ France v Police [2014] NZHC 2193 (10 September 2014), High Court (New Zealand).

- ^ Carlin, John P. (October 14, 2015). "Assistant Attorney General John P. Carlin Delivers Remarks on Domestic Terrorism at an Event Co-Sponsored by the Southern Poverty Law Center and the George Washington University Center for Cyber and Homeland Security's Program on Extremism". U.S. Department of Justice News. Archived from the original on October 15, 2015. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ "Assistant Attorney General John Carlin on Domestic Terrorism Threat". C-SPAN. October 14, 2015. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved October 15, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Kent, Stephen A. (2015). "Freemen, Sovereign Citizens, and the Challenge to Public Order in British Heritage Countries" (PDF). International Journal of Cultic Studies. 6. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Cocks, Joan (Spring 2018), "Immune from the Law?", Lapham's Quarterly, archived from the original on March 15, 2018, retrieved January 11, 2020

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stocken, Shelley (July 8, 2016). "The seriously weird beliefs of Freemen on the land". NewsComAu. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ "Freeman on the land (sovereign citizens)". You've entered law land. September 16, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2021. Note: This is a blog, but it contains useful links to the cases on Austlii, and summaries written by a lawyer.

- ^ Vincent, Sam (November 2016), "Eyes wide open", The Monthly, archived from the original on July 23, 2019, retrieved January 8, 2020

- ^ Koziol, Michael (August 6, 2016), "One Nation senator Malcolm Roberts wrote bizarre 'sovereign citizen' letter to Julia Gillard", The Sydney Morning Herald, archived from the original on March 13, 2018, retrieved January 8, 2020

- ^ "Home page". Original Sovereign Tribal Federation. Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Glazov, Ramon (September 6–12, 2014). "Freemen movement targets Indigenous Australia". The Saturday Paper (28). Retrieved April 7, 2021.

- ^ Thomas, James; McGregor, Jeanavive (November 30, 2015). "Sovereign citizens: Terrorism assessment warns of rising threat from anti-government extremists". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on November 30, 2015. Retrieved April 4, 2021.

- ^ "U R Australia". Facebook. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Hutchinson, Jade (October 3, 2018). "The 'Right' Kind of Dogma". VOX - Pol. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Dyck, Darryl (January 25, 2015), "'Sovereign citizen' movement worrying officials as 30,000 claim they 'freed' themselves from Canada's laws", National Post, retrieved January 11, 2020

- ^ Netolitzky, Donald J. (2018). "Organized Pseudolegal Commercial Arguments as Magic and Ceremony". Alberta Law Review: 1045. doi:10.29173/alr2485. ISSN 1925-8356.

- ^ Hebert, David Gauvey (May 19, 2020), "The King of Germany Will Accept Your Bank Deposits Now", BloomburgBusinessweek, retrieved June 23, 2020

- ^ Schuetze, Christopher F. (March 19, 2020), "Germany Shuts Down Far-Right Clubs That Deny the Modern State", The New York Times, retrieved June 23, 2020

- ^ Marko, Karoline (2020). "'The rulebook – our constitution': a study of the 'Austrian Commonwealth's' language use and the creation of identity through ideological in- and out-group presentation and legitimation". Critical Discourse Studies: 1–17. doi:10.1080/17405904.2020.1779765. ISSN 1740-5904.

- ^ Hartleb, Florian (2020). Lone Wolves: The New Terrorism of Right-Wing Single Actors. Springer Nature. p. 140. ISBN 978-3-030-36153-2.

- ^ 'President' of Austrian anti-state group jailed for 14 years, Agence France-Presse, January 25, 2019, retrieved June 23, 2020

- ^ "Schaeffer Cox, 'sovereign citizen'", Anchorage Daily News, September 30, 2016, retrieved January 8, 2020

- ^ Bever, Lindsey (November 14, 2017), "Jared Fogle just tried to get out of his sex-crime sentence with a legal Hail Mary", The Washington Post, archived from the original on January 13, 2018, retrieved January 12, 2018

- ^ Johnson, Kevin (March 30, 2012), "Anti-government 'sovereign movement' on the rise in U.S.", USA Today, archived from the original on March 5, 2016, retrieved January 12, 2018

- ^ Weill, Kelly (January 4, 2018), "Republican Lawmaker: Recognize Sovereign Citizens or Pay $10,000 Fine", Daily Beast, retrieved August 4, 2020

- ^ Gavin, Robert (April 22, 2014), "Prison for anti-tax activist who was once a child star", Albany Times Union, archived from the original on November 15, 2019, retrieved January 8, 2020

External links

- Sovereign Citizen Movement Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC)

- SPLC's Video Informing Law Enforcement on the Dangers of "Sovereign Citizens"

- FBI page on the Sovereign Citizen movement

- Sovereign Citizen Movement – Anti-Defamation League

- 10 tips and tactics for investigating Sovereign Citizens (PoliceOne)

- 60 Minutes documentary about Sovereign citizens

- The Freeman-on-the-Land movement (Bencher's Bulletin guide for British Columbian lawyers)

- Guide to managing sovereign citizens (Police magazine)

- "A quick guide to Sovereign Citizens" (UNC School of Government)

- "Common Law and Uncommon Courts: An Overview of the Common Law Court Movement", Mark Pitcavage, The Militia Watchdog Archives, Anti-Defamation League, July 25, 1997.

- Without Prejudice: What Sovereign Citizens Believe, J.M. Berger, GWU Program on Extremism, June 2016

- "Sovereign citizens: A narrative review with implications of violence towards law enforcement"

- "Sovereign Citizens - A Psychological and Criminological Analysis"

- Sovereign citizen movement

- Anti-Federalism

- Far-right politics in the United States

- Fringe theories

- Tax resistance in the United States

- Terrorism in the United States

- Paleoconservatism

- Paleolibertarianism

- Right-wing militia organizations in the United States

- Pseudolaw