Mecklenburg County, North Carolina

Coordinates: 35°15′N 80°50′W / 35.25°N 80.83°W

Mecklenburg County | |

|---|---|

U.S. county | |

| |

Flag  Seal | |

Location within the U.S. state of North Carolina | |

North Carolina's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 35°15′N 80°50′W / 35.25°N 80.83°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | November 6, 1762 |

| Named for | Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz |

| Seat | Charlotte |

| Largest city | Charlotte |

| Area | |

| • Total | 546 sq mi (1,410 km2) |

| • Land | 524 sq mi (1,360 km2) |

| • Water | 22 sq mi (60 km2) 4.0%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 1,128,945 |

| • Density | 2,154.48/sq mi (831.85/km2) |

| Demonym(s) | Mecklenburger |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional districts | 9th, 12th |

| Website | www |

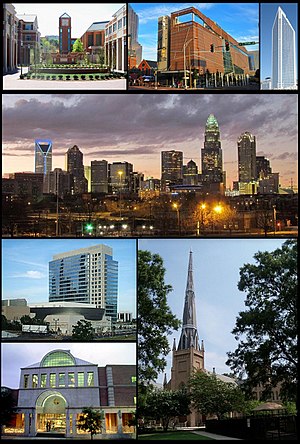

Mecklenburg County is a county located in the southwestern region of the state of North Carolina, in the United States. As of the 2010 census, the population was 919,618. It increased to 1,110,356 as of the 2019 estimate, making it the second-most populous county in North Carolina (after Wake County) and the first county in the Carolinas to surpass one million in population.[1] Its county seat is Charlotte, and is the state's largest city.[2]

Mecklenburg County is the central county of the Charlotte-Concord-Gastonia, NC-SC Metropolitan Statistical Area. On September 12, 2013, the county welcomed its one millionth resident.[3]

Like its seat, the county is named after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, Queen of the United Kingdom, whose name is derived from the region of Mecklenburg in Germany, itself deriving its name from Mecklenburg Castle (Mecklenburg meaning "large castle" in Low German) in the village of Dorf Mecklenburg.

History[]

Mecklenburg County was formed in 1762 from the western part of Anson County, both in the Piedmont section of the state. It was named in commemoration of the marriage of King George III to Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz,[4] for whom the county seat Charlotte is named. Due to unsure boundaries, a large part of south and western Mecklenburg County extended into areas that would later form part of the state of South Carolina. In 1768, most of this area (the part of Mecklenburg County west of the Catawba River) was designated Tryon County, North Carolina.

Determining the final boundaries of these "western" areas between North and South Carolina was a decades-long process. As population increased in the area following the American Revolutionary War, in 1792 the northeastern part of Mecklenburg County was taken by the North Carolina legislature for Cabarrus County. Finally, in 1842 the southeastern part of Mecklenburg County was combined with the western part of Anson County to become Union County.

The Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence was allegedly signed on May 20, 1775; if the document is genuine, Mecklenburg County was the first part of the Thirteen Colonies to declare independence from Great Britain.[5] The "Mecklenburg Resolves" were adopted on May 31, 1775. Mecklenburg continues to celebrate the Meck Dec each year in May.[6] The date of the Mecklenburg Declaration is also listed on the flag of North Carolina, represented by the date of May 20, 1775 as one of two dates on the flag of the old North State.

Geography[]

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 546 square miles (1,410 km2), of which 524 square miles (1,360 km2) is land and 22 square miles (57 km2) (4.0%) is water.[7]

Adjacent counties[]

- Iredell County - north

- Cabarrus County - northeast

- Union County - southeast

- Lancaster County, South Carolina - south

- York County, South Carolina - southwest

- Gaston County - west

- Catawba County - northwest

- Lincoln County - northwest

Demographics[]

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 11,395 | — | |

| 1800 | 10,439 | −8.4% | |

| 1810 | 14,272 | 36.7% | |

| 1820 | 16,895 | 18.4% | |

| 1830 | 20,073 | 18.8% | |

| 1840 | 18,273 | −9.0% | |

| 1850 | 13,914 | −23.9% | |

| 1860 | 17,374 | 24.9% | |

| 1870 | 24,299 | 39.9% | |

| 1880 | 34,175 | 40.6% | |

| 1890 | 42,673 | 24.9% | |

| 1900 | 55,268 | 29.5% | |

| 1910 | 67,031 | 21.3% | |

| 1920 | 80,695 | 20.4% | |

| 1930 | 127,971 | 58.6% | |

| 1940 | 151,826 | 18.6% | |

| 1950 | 197,052 | 29.8% | |

| 1960 | 272,111 | 38.1% | |

| 1970 | 354,656 | 30.3% | |

| 1980 | 404,270 | 14.0% | |

| 1990 | 511,433 | 26.5% | |

| 2000 | 695,454 | 36.0% | |

| 2010 | 919,628 | 32.2% | |

| 2020 | 1,115,482 | 21.3% | |

As of the census[8] of 2000, there were 695,454 people, 273,416 households, and 174,986 families residing in the county. The population density was 1,322 people per square mile (510/km2). There were 292,780 housing units at an average density of 556 per square mile (215/km2). The racial makeup of the county was 64.02% White, 27.87% Black or African American, 0.35% American Indian/Alaska Native, 3.15% Asian, 0.05% Pacific Islander, 3.01% from other races, and 1.55% from two or more races. 6.45% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 273,416 households, out of which 32.10% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 47.70% were married couples living together, 12.40% had a female householder with no husband present, and 36.00% were non-families. 27.60% of all households were made up of individuals, and 5.90% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.49 and the average family size was 3.06.

In the county, the population was spread out, with 25.10% under the age of 18, 9.70% from 18 to 24, 36.40% from 25 to 44, 20.30% from 45 to 64, and 8.60% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 33 years. For every 100 females there were 96.50 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 93.60 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $50,579, and the median income for a family was $60,608. Males had a median income of $40,934 versus $30,100 for females. The per capita income for the county was $27,352. About 6.60% of families and 9.20% of the population were below the poverty line, including 11.50% of those under age 18 and 9.30% of those age 65 or over.

Mecklenburg County Government[]

Mecklenburg County is a member of the regional Centralina Council of Governments.[9]

The county is governed by the Mecklenburg Board of County Commissioners (BOCC). The BOCC is a nine-member board made up of representatives from each of the six county districts and three at-large representatives elected by the entire county. This electoral structure favors candidates in the at-large positions who will be elected by the majority population of the county. Each District has a population of approximately 165,000 individuals. All seats are partisan and are for 2-year terms (elections occur in even years). The current chairman of the Mecklenburg BOCC is George Dunlap (D, District 3). The Current Vice-Chair is Elaine Powell (D, District 1).

Members of the Mecklenburg County Commission are required by North Carolina State law to choose a Chair and Vice-Chair once a year (at the first meeting of December). Historically, the individual elected was the 'top-vote-getter' which was one of three at-large members. In 2014 this unofficial rule was changed by the Board to allow any member to serve as Chair or Vice-chair as long as they received support from 4 members plus their own vote.

The nine members of the Board of County Commissioners are:[10]

- George Dunlap (D, District 3, Chairman)

- Elaine Powell (D, District 1, Vice Chairman)

- Pat Cotham (D, At-Large)

- Trevor Fuller (D, At-Large)

- Ella Scarborough (D, At-Large)

- Vilma Leake (D, District 2)

- Mark Jerrell (D, District 4)

- Susan B. Harden (D, District 5)

- Susan Rodriguez-McDowell (D, District 6)

Law, government and politics[]

Prior to 1928, Mecklenburg County was strongly Democratic, similar to most counties in the Solid South. For most of the time from 1928 to 2000, it was a bellwether county, only voting against the national winner in 1960 and 1992. For most of the second half of the 20th century, it leaned Republican in most presidential elections. From 1952 to 2000, a Democrat only won a majority of the county's vote twice, in 1964 and 1976; Bill Clinton only won a slim plurality in 1996.

However, it narrowly voted for John Kerry in 2004 even as he lost both North Carolina and the election. It swung hard to Barack Obama in 2008, giving him the highest margin for a Democrat in the county since Franklin D. Roosevelt's landslides. Obama's margin in Mecklenburg was enough for him to narrowly win the state. It voted for Obama by a similar margin in 2012, and gave equally massive wins to Hillary Clinton in 2016 and Joe Biden in 2020. Since 2008, Mecklenburg County has been one of the most Democratic urban counties in the South and the third-strongest Democratic bastion in the I-85 Corridor, behind only Orange and Durham counties.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS)[]

The second largest school system in North Carolina behind Wake County Public Schools. The current Chairman of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg School board is Mary T. McCray (At-Large). The Vice Chair is Ericka Ellis-Stewart (At-Large). The members of the Board of Education are:

- Mary T. McCray (At-Large - Chairman)

- Elyse C. Dashew (At-Large - Vice Chair)

- Ericka Ellis-Stewart (At-Large)

- Rhonda Lennon (District 1)

- Thelma Byers-Bailey (District 2)

- Ruby M. Jones(District 3)

- Tom Tate (District 4)

- Eric C. Davis (District 5)

- Paul Bailey (District 6)

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg School board is non-partisan, and staggered elections are held every two years (in odd years).

MEDIC[]

The residents of Mecklenburg County are provided emergency medical service by MEDIC, the Mecklenburg EMS Agency. All emergency ambulance service is provided by MEDIC. No other emergency transport companies are allowed to operate within Mecklenburg County. While MEDIC is a division of Mecklenburg County Government, a board guides and directs MEDIC that consists of members affiliated with Atrium Health, Novant Health and a swing vote provided by the Mecklenburg County Board of Commissioners. Atrium and Novant are the two major medical institutions in Charlotte, North Carolina.

Economy[]

The major industries of Mecklenburg County are banking, manufacturing, and professional services, especially those supporting banking and medicine. Mecklenburg County is home to ten Fortune 500 companies.[12]

| Name | Industry | 2019 Revenue | Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Bank of America | Banking | $110.6 billion | 25[13] |

| 2. | Nucor | Metals | $25.1 billion | 120[13] |

| 3. | Duke Energy | Utilities | $24.1 billion | 126[13] |

| 4. | Sonic Automotive | Automotive retailing | $10.0 billion | 316[13] |

| 5. | Brighthouse Financial | Insurance | $9.0 billion | 342[13] |

| 6. | Sealed Air | Conglomerate | $4.7 billion | 555[13] |

| 7. | Coca-Cola Consolidated | Food Processing | $4.7 billion | 563[13] |

| 8. | JELD-WEN Holding | Building Products | $4.3 billion | 590[13] |

| 9. | Albemarle | Chemicals | $3.4 billion | 702[13] |

| 10. | SPX | Electronics | $2.1 billion | 962[13] |

Wachovia, a former Fortune 500 company, had its headquarters in Charlotte until it was acquired by Wells Fargo for $15.1 billion. Wells Fargo maintains the majority of the former company's operations in Charlotte.[14]

Goodrich Corporation, a former Fortune 500 company, had its headquarters in Charlotte until it was acquired by United Technologies Corporation for $18.4 billion. Charlotte is now the headquarters for UTC Aerospace Systems.[15]

| Name | Industry | Number of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Atrium Health | Health Care and Social Assistance | 35,700 |

| 2. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools | Educational Services | 18,495 |

| 3. Bank of America | Finance and Insurance | 15,000 |

| 4. American Airlines | Transportation and Warehousing | 11,000 |

| 5. Harris Teeter | Retail Trade | 8,239 |

| 6. Duke Energy | Utilities | 7,900 |

| 7. City of Charlotte | Public Administration | 6,800 |

| 8. Mecklenburg County Government | Public Administration | 5,512 |

| 9. YMCA of Greater Charlotte | Arts, Entertainment and Recreation | 4,436 |

| 10. Carowinds | Arts, Entertainment and Recreation | 4,100 |

| 11. University of North Carolina at Charlotte | Educational Services | 4,000 |

| 11. United States Postal Service | Transportation and Warehousing | 4,000 |

| 11. TIAA | Finance and Insurance | 4,000 |

| 14. LPL Financial | Finance and Insurance | 2,850 |

| 15. Central Piedmont Community College | Educational Services | 2,700 |

| 16. Belk | Retail Trade | 2,300 |

| 17. DMSI | Transportation and Warehousing | 2,175 |

| 18. IBM | Professional Services | 2,100 |

| 19. Robert Half International | Administrative and Support Services | 2,000 |

| 19. Allstate Insurance | Finance and Insurance | 2,000 |

Education[]

School system[]

The Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools (CMS) serves the entire county; however, the State of North Carolina also has approved a number of charter schools in Mecklenburg County (independently operated schools financed with tax dollars).

Colleges and universities[]

Current[]

- University of North Carolina at Charlotte

- Davidson College

- Queens University of Charlotte

- Central Piedmont Community College

- Johnson & Wales University

- Johnson C. Smith University

Former[]

Libraries[]

The Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County serves residents of Mecklenburg County. Library cards from any branch can be used at all 20 locations. The library has an extensive collection (over 1.5 million items) of reference and popular materials including DVDs, books on CD, best sellers, downloadable media, and books.

The Billy Graham Library contains the papers and memorabilia related to the career of the well-known 20th century evangelist, Billy Graham.

Transportation[]

Air[]

The county's primary commercial aviation airport is Charlotte Douglas International Airport in Charlotte, the 12th largest airport in the USA.[17][circular reference]

Intercity rail[]

With twenty-five freight trains a day, Mecklenburg is a freight railroad transportation center, largely due to its place on the NS main line between Washington and Atlanta and the large volumes of freight moving in and out of the county via truck.

Mecklenburg County is served daily by three Amtrak routes.

The Crescent train connects Charlotte with New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Charlottesville, and Greensboro to the north, and Atlanta, Birmingham and New Orleans to the south.

The Carolinian train connects Charlotte with New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, Raleigh, Durham and Greensboro.

The Piedmont train connects Charlotte with Raleigh, Durham and Greensboro.

The Amtrak station is located at 1914 North Tryon Street. A new centralized multimodal train station, Gateway Station, has been planned for the city. It is expected to house the future LYNX Purple Line, the new Greyhound bus station, and the Crescent line that passes through Uptown Charlotte.

Mecklenburg County is the proposed southern terminus for the initial segment of the Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor operating between Charlotte and Washington, D.C. Currently in conceptual design, the SEHSR would eventually run from Washington, D.C. to Macon, Georgia.

Light rail and mass transit[]

Light rail service in Mecklenburg County is provided by LYNX Rapid Transit Services. Currently, the 19-mile (31 km) Lynx Blue Line runs from University of North Carolina at Charlotte, through Uptown Charlotte, to Pineville; build-out is expected to be complete by 2034. The CityLynx Gold Line, a 1.5-mile (2.4 km) streetcar line runs from the Charlotte Transportation Center to Hawthorne Lane & 5th Street, with additional stops to French Street in Biddleville and Sunnyside Avenue currently under construction.

Charlotte Area Transit System (CATS) bus service serves all of Mecklenburg County, including Charlotte, and the municipalities of Davidson, Huntersville, Cornelius, Matthews, Pineville, and Mint Hill.

The vintage Charlotte Trolley also operates in partnership with CATS. On July 14, 2015, the was revived to operate in Uptown after several decades of absence. The line runs from Trade Street, near and Convention Center, to . In addition to several restaurants, this line also serves Central Piedmont Community College and Novant Health Presbyterian Hospital. The city is applying for a $50 million to gain funding to construct expansion of a line to serve Johnson C. Smith University to the West and East along Central Avenue.

Freight[]

Mecklenburg's manufacturing base, its central location on the Eastern Seaboard, and the intersection of two major interstates in the county have made it a hub for the trucking industry.

Major roadways[]

Arts and culture[]

Museums and libraries[]

- Bechtler Museum of Modern Art

- Billy Graham Library

- Carolinas Aviation Museum

- Charlotte Museum of History

- Charlotte Nature Museum

- Discovery Place

- Discovery Place KIDS-Huntersville

- Harvey B. Gantt Center for African-American Arts + Culture

- ImaginOn

- Levine Museum of the New South

- McColl Center for Visual Art

- Mint Museum Randolph

- Mint Museum UPTOWN

- NASCAR Hall of Fame

- Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County

Sports and entertainment[]

- Carolina Panthers

- Charlotte Hornets

- Charlotte Independence

- Charlotte Hounds

- Charlotte Checkers

- Charlotte Knights

- Charlotte Motor Speedway

- Bank of America Stadium

- Truist Field

- Knights Stadium

- American Legion Memorial Stadium

Music and performing arts venues[]

- Actor's Theatre of Charlotte

- Bojangles' Coliseum

- Carolina Actors Studio Theatre

- ImaginOn

- Knight Theater

- The Neighborhood Theatre in NoDa

- North Carolina Blumenthal Performing Arts Center

- Ovens Auditorium

- Spectrum Center (arena)

- Spirit Square

- Theatre Charlotte

- Uptown Amphitheatre At the NC Music Factory

- PNC Music Pavilion

- Morrison YMCA Amphitheatre

Amusement parks[]

- Carowinds

- Great Wolf Lodge

- Ray's Splash Planet

Other attractions[]

- Carolina Place Mall

- Carolina Raptor Center

- Concord Mills Mall in Cabarrus County

- Lake Norman

- Lake Wylie

- Latta Plantation Nature Preserve

- Little Sugar Creek Greenway

- Mecklenburg County Aquatic Center

- Northlake Mall

- President James K. Polk Historic Site

- Ray's Splash Planet

- SouthPark Mall

- U.S. National Whitewater Center

- Charlotte Premium Outlets

Communities[]

Mecklenburg County contains seven municipalities including the City of Charlotte and the towns of Cornelius, Davidson, and Huntersville (north of Charlotte); and the towns of Matthews, Mint Hill, and Pineville (south and southeast of Charlotte). Small portions of Stallings and Weddington are also in Mecklenburg County, though most of those towns are in Union County. Extraterritorial jurisdictions within the county are annexed by municipalities as soon as they reach sufficient concentrations.

City[]

- Charlotte (county seat)

Towns[]

- Cornelius

- Davidson

- Huntersville

- Matthews

- Mint Hill

- Pineville

- Stallings

- Weddington

Unincorporated communities[]

- Caldwell

- Hopewell

- Mountain Island

- Newell

- Prosperity Village Area

- Sterling[18]

Townships[]

- Berryhill

- Charlotte

- Clear Creek

- Crab Orchard

- Deweese

- Huntersville

- Lemley

- Long Creek

- Mallard Creek

- Morning Star

- Paw Creek

- Pineville

- Providence

- Sharon (extinct)

- Steele Creek

Notable people[]

- Abraham Alexander (1717–1786), on the commission to establish town of Charlotte, North Carolina, North Carolina state legislator[19]

- Evan Shelby Alexander (1767–1809), born in Mecklenburg County, later United States Congressman from North Carolina[19]

- Nathaniel Alexander (1756–1808), born in Mecklenburg County, United States Congressman and governor of North Carolina[19]

- Nellie Ashford (born c. 1943), folk artist born in Mecklenburg County[20]

- Romare Bearden (1911-1988), 20th century African-American artist[21]

- Brigadier General William Lee Davidson (1746-1781), was a North Carolina militia general during the American Revolutionary War.

- Ric Flair (born 1949), retired professional wrestler

- Anthony Foxx (born 1971), former United States Secretary of Transportation, former mayor of Charlotte.

- Billy Graham (1918-2018), world-famous evangelist

- Eliza Ann Grier (1864–1902), born in Mecklenburg County, first African-American female physician in Georgia

- Anthony Hamilton (born 1971), American R&B/soul singer

- Daniel Harvey Hill (1821-1889), Confederate General during the American Civil War and a Southern scholar.

- Gen. Robert Irwin (North Carolina State Senator) (1738-1800), a distinguished commander of Patriot (American Revolution) militia forces, who is said to have been a signer of the Mecklenburg Declaration of Independence

- Pat McCrory (born 1956), former Governor of North Carolina, former seven-term Mayor of Charlotte.

- James K. Polk (1795–1849), 11th President of the United States. Polk was born in Mecklenburg County in 1795; his family moved to Tennessee when he was an adolescent.

- Colonel William Polk (1758–1834) banker, educational administrator, political leader, renowned Continental officer in the War for American Independence, and survivor of the 1777/1778 encampment at Valley Forge.

- Shannon Spake (born 1976), ESPN NASCAR correspondent

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2015.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-05-24. Retrieved 2014-05-23.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 204.

- ^ "Did North Carolina Issue the First Declaration of Independence?". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ^ Williams, James H. (June 10, 2008). "The Mecklenburg Declaration – History". www.meckdec.org. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ^ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Archived from the original on January 12, 2015. Retrieved January 18, 2015.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ^ "Centralina Council of Governments". Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- ^ "Board of County Commissioners". Retrieved January 20, 2019.

- ^ Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- ^ "Fortune 500 Companies". Charlotte Chamber Web Site. Retrieved 2013-07-15.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j "Fortune 500". Fortune. Retrieved 2020-04-17.

- ^ "FRB: Press Release--Approval of proposal by Wells Fargo & Company to acquire Wachovia Corporation". Federal Reserve Board. 2008-10-12. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ^ United Technologies completes Goodrich acquisition

- ^ "Major Employers in Charlotte Region - Charlotte Area Major Employers (Q2 2018)" (PDF). Charlotte Regional Business Alliance. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- ^ "List of the busiest airports in the United States". Wikipedia. 3 August 2020.

- ^ Sterling, Charlotte, NC (Google Maps, accessed 5 August 2020)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Who Was Who in America, Historical Volume, 1607-1896. Chicago: Marquis Who's Who. 1963.

- ^ "Nellie Ashford: Life, Liberty, and the Lack Thereof". NCCU | myEOL. Retrieved 2019-12-24.

- ^ "Home - Bearden Foundation". www.beardenfoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2013-05-23. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

External links[]

Geographic data related to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to Mecklenburg County, North Carolina at OpenStreetMap- Quickfacts.census.gov

- Charlotte-Mecklenburg County Government Official Website

- Mecklenburg County homepage

- NCGenWeb Mecklenburg County - free genealogy resources for the county

- Public Library of Charlotte and Mecklenburg County

- Charlotte Mecklenburg Schools

- Mecklenburg County Parks and Recreation

- North Carolina counties

- Mecklenburg County, North Carolina

- 1762 establishments in North Carolina

- Populated places established in 1762

- Charlotte metropolitan area