Pump Up the Volume (film)

| Pump Up the Volume | |

|---|---|

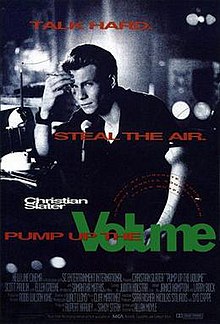

Theatrical poster | |

| Directed by | Allan Moyle |

| Written by | Allan Moyle |

| Produced by | Syd Cappe Sara Risher Sandy Stern Nicolas Stiliadis |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Walt Lloyd |

| Edited by | Larry Rock |

| Music by | Cliff Martinez |

| Distributed by | New Line Cinema |

Release date | August 22, 1990 |

Running time | 105 minutes |

| Countries | United States, Canada |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $11.5 million (United States)[1] |

Pump Up the Volume is a 1990 American coming-of-age drama film written and directed by Allan Moyle and starring Christian Slater and Samantha Mathis.

Plot[]

High school student Mark Hunter, who lives in a sleepy suburb of Phoenix, Arizona, starts an FM pirate radio station that broadcasts from his parents' basement and functions as his sole outlet for his teenage angst and aggression. His pirate station's theme song is "Everybody Knows" by Leonard Cohen and there are glimpses of cassettes by such alternative musicians as The Jesus and Mary Chain, Camper Van Beethoven, Primal Scream, Soundgarden, Ice-T, Bad Brains, Concrete Blonde, Henry Rollins, and Pixies. By day, Mark is seen as a loner who has to force himself to be sociable around others; by night, he expresses his outsider views about the problems with American society. When he speaks his mind about what is going on at his school and in the community, his fellow students increasingly tune in to hear his show.

Nobody knows the true identity of "Hard Harry" or "Happy Harry Hard-on," as Mark refers to himself until fellow student Nora Diniro locates and confronts him the day after a student named Malcolm commits suicide after Harry attempts to reason with him. The radio show becomes increasingly popular and influential after Harry confronts the suicide head-on, exhorting his listeners to confront their problems instead of surrendering to them through suicide—at the crescendo of his yelled speech, an overachieving student named Paige Woodward (who has been a constant listener) jams her various medals and accolades into a microwave and turns it on. She then sits, watching the awards cook until the microwave explodes, injuring her. While this is happening, other students act out in cathartic release.

Eventually, the radio show causes so much trouble in the community that the FCC is called in to investigate. During the fracas, it is revealed that the school's principal, Loretta Cresswood, has been expelling "problem students," namely, students with below-average standardized test scores, to boost the district's test scores while still keeping their names on the rolls (a criminal offense) to retain government funding.

Realizing he has started something huge, Mark decides to end it. He dismantles his radio station and attaches it to his mother's old Jeep, creating a mobile transmitter so authorities can't triangulate his position. Pursued by the police and the FCC, Nora drives the Jeep around while Mark broadcasts. The harmonizer he uses to disguise his voice breaks, and Mark, unable to fix it, decides to broadcast his final message as himself. They finally drive up to the crowd of protesting students, and Mark tells them that the world belongs to them and that they should make their own future. The police step in and arrest Mark and Nora. As the pair are taken away, Mark reminds the students to "talk hard." As the film ends, the voices of other students (and even one of the teachers) speak as intros for their own independent stations, which can be heard broadcasting across the country.

Cast[]

- Christian Slater as Mark Hunter

- Samantha Mathis as Nora Diniro

- Mimi Kennedy as Marla Hunter

- Scott Paulin as Brian Hunter

- Cheryl Pollak as Paige Woodward

- Annie Ross as Principal Loretta Creswood

- Ahmet Zappa as Jaime

- Billy Morrissette as Mazz Mazzilli

- Seth Green as Joey

- Robert Schenkkan as David Deaver, guidance counselor

- Ellen Greene as Jan Emerson

- Andy Romano as Mr. Murdock

- Anthony Lucero as Malcolm Kaiser

- Lala Sloatman as Janie

- James Hampton as Arthur Watts of the FCC

Production[]

After his film Times Square, a new wave comedy, was taken away from him and re-edited, Allan Moyle retired from directing and began working on screenplays. One of them, about a teenager who runs his own pirate radio station for other teenagers, came to the attention of SC Entertainment, a Toronto-based company, and put into development.[2] He was persuaded to direct his own screenplay. Moyle wrote it without a specific actor in mind but his development deal specified that the project would be canceled if a suitable actor could not be found. The director needed an actor who had to have "glee, to be ineffably sweet and at the same time demonic."[2] He initially wanted to cast John Cusack, but Cusack turned down the role, as he didn't want to play another high school student following his role in Say Anything...[3] Christian Slater met with Moyle and producer Sandy Stern and displayed all these qualities. Moyle has described the film's protagonist as an amalgam of Holden Caulfield and Lenny Bruce[2] and the "Hard Harry" persona as a guy who "has to get credibility as an outsider. As the last angry man on the planet, he has to use the foulest language he can think of. He even pretends to masturbate on the air. He's obsessed with sex and death."[4] The school in the film, Hubert Humphrey High, was based on a Montreal high school where director Moyle's sister used to teach that, according to Moyle, had a principal "who had a pact with the staff to enhance the credibility of the school scholastically at the expense of the students who were immigrants or culturally disabled in some way or another."[4]

Slater disagreed with Moyle who wanted to bring in a tap dance instructor to help orchestrate a scene that begins with "Hard Harry" faking masturbation on the air and ends with him breaking into a manic dance by himself. Slater wanted to do something more spontaneous based on his instincts.[5]

Reception[]

Pump Up the Volume failed to catch on at the box office. When it was released on August 24, 1990, in 799 theaters, it grossed USD $1.6 million in its opening weekend. It went on to make $11.5 million in North America.[6]

The film received generally positive reviews from critics and is currently rated 81% at Rotten Tomatoes based on 36 reviews. In his review for the New York Times, Stephen Holden wrote, "Much like Heathers, Pump Up the Volume doesn't know how to draw out its premise, once that premise has been thoroughly explored. As the film accelerates toward its conclusion, the strands of its clever plot are too hastily and perfunctorily resolved . . . Working within the confines of the teen-age genre film, however, Pump Up the Volume still succeeds in sounding a surprising number of honest, heartfelt notes".[7] USA Today gave the film three-and-a-half stars out of four, praising the film's conclusion: "the ending, though in part contrived, doesn't cop out".[8]

Awards[]

The movie won the Golden Space Needle Award at the Seattle International Film Festival, beating out the festival favorite, Denys Arcand's Jesus of Montreal. Reportedly, some audience members booed when the film was named the winner.[4] Moyle's film also won the Audience Award at the Deauville Film Festival.[9]

Musical adaptation[]

In 2019, Point Park University's Conservatory of Performing Arts announced that it would be producing the world premiere production of the musical adaptation in conjunction with RWS Entertainment as a part of their 2019-2020 season. Jeff Thompson, composer, and Jeremy Desmon, book and lyrics, first started the project in 2006. They brought the preliminary script and music to workshop sessions at Godspeed Musicals, The Human Race Theatre, and finally Seattle's 5th Avenue Theatre in 2016 to "test its legs".[10]

The world premiere production was set to open April 3, 2020 at Pittsburgh Playhouse's Highmark Theater, but was put on hiatus due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[11][third-party source needed]

Soundtrack[]

References[]

- ^ "Pump Up the Volume (1990)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ a b c Scott, Jay (September 12, 1990). "Festival of Festivals In Person". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ Ducker, Eric (21 August 2020). "Talk Hard: The Making of the Teen-Angst Classic 'Pump Up the Volume'". The Ringer. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

- ^ a b c Portman, Jamie (August 22, 1990). "Movie Views Cruel World of Today's Teenage Angst". Toronto Star.

- ^ Yakir, Dan (October 2, 1990). "Christian Slater Incites the Passions of an Entire High School in Pump Up the Volume". The Globe and Mail.

- ^ "Pump Up the Volume". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (August 22, 1990). "A Rebellious Teen-Ager Takes to the Airwaves". New York Times. Retrieved 2008-03-03.

- ^ Clark, Mike (August 22, 1990). "Slater turbocharges an energetic Volume". USA Today.

- ^ Zekas, Rita (September 11, 1990). "The making of a festival hero". Toronto Star.

- ^ Hetrick, Adam (July 29, 2016). "Pump Up the Volume Musical Will Test Legs in Seattle". Playbill. Retrieved 2020-01-15.

- ^ "Shows". www.pittsburghplayhouse.com. Retrieved 2020-01-15.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pump Up the Volume |

- English-language films

- 1990 films

- 1990s coming-of-age drama films

- American coming-of-age drama films

- American films

- 1990s teen drama films

- American teen drama films

- 1990s English-language films

- Films about pirate radio

- Films about freedom of expression

- Films shot in California

- Films set in Maricopa County, Arizona

- Films about radio people

- Films directed by Allan Moyle

- Films scored by Cliff Martinez