Pyramid of Nyuserre

| Pyramid of Nyuserre | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||

| Nyuserre Ini | |||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 29°53′44″N 31°12′13″E / 29.89556°N 31.20361°ECoordinates: 29°53′44″N 31°12′13″E / 29.89556°N 31.20361°E | ||||||||||||||||

| Ancient name |

Mn-swt Nỉ-wsr-Rꜥ Men-sut Ni-user-Re[1] "Enduring are the places of Nyuserre"[2] Alternatively translated as "The places of Nyuserre Endure"[3] or "Established are the places of Nyuserre"[4] | ||||||||||||||||

| Constructed | Fifth Dynasty (c. 25th century BC) | ||||||||||||||||

| Type | Smooth-sided (now ruined) | ||||||||||||||||

| Material | Limestone | ||||||||||||||||

| Height | 51.68 m (169.6 ft; 98.63 cu)[5] | ||||||||||||||||

| Base | 78.9 m (259 ft; 150.6 cu)[5] | ||||||||||||||||

| Volume | 112,632 m3 (147,317 cu yd)[6] | ||||||||||||||||

| Slope | 51° 50' 35[5] | ||||||||||||||||

Location within Lower Egypt | |||||||||||||||||

The Pyramid of Nyuserre (Egyptian: Mn-swt Nỉ-wsr-rꜥ, meaning "Enduring are the places of Nyuserre") is a mid-25th-century BC pyramid complex built for the Egyptian pharaoh Nyuserre Ini of the Fifth Dynasty.[7][a] During his reign, Nyuserre had the unfinished monuments of his father, Neferirkare Kakai, mother, Khentkaus II, and brother, Neferefre, completed, before commencing work on his personal pyramid complex. He chose a site in the Abusir necropolis between the complexes of Neferirkare and Sahure, which, restrictive in area and terrain, economized the costs of labour and material. Nyuserre was the last king to be entombed in the necropolis; his successors chose to be buried elsewhere. His monument encompasses a main pyramid, a mortuary temple, a valley temple on Abusir Lake, a causeway originally intended for Neferirkare's monument, and a cult pyramid.

The main pyramid had a stepped core built from rough-cut limestone and encased in fine Tura limestone. The casing was stripped down by stone thieves, leaving the core exposed to the elements and further human activity, which have reduced the once nearly 52 m (171 ft; 99 cu) tall pyramid to a mound of ruins, with a substructure that is dangerous to enter due to the risk of cave-ins. Adjoining the pyramid's east face is the mortuary temple with its unusual configuration and features. Replacing the usual T-shape plan, the mortuary temple has an L-shape; an alteration required due to the presence of mastabas to the east. It debuted the antichambre carrée, a square room with a single column, which became a standard feature of later monuments. It also contains an unexplained square platform which has led archaeologists to suggest that there may be a nearby obelisk pyramidion. This is unusual as obelisks were central features of Egyptian sun temples, but not of pyramid complexes. Finally, the north-east and south-east corners of the site have two structures which appear to have been pylon prototypes. These became staple features of temples and palaces. In the south-east corner of the complex, a separate enclosure hosts the cult pyramid – a small pyramid whose purpose remains unclear. A long causeway binds the mortuary and valley temples. These two were under construction for Neferirkare's monument, but were repurposed for that of Nyuserre. The causeway, which had been more than half completed when Neferirkare died, thus has a bend where it changes direction from Neferirkare's mortuary temple towards Nyuserre's.

Two other pyramid complexes have been found in the area. Known as Lepsius XXIV and Lepsius XXV, they may have belonged to the consorts of Nyuserre, particularly Queen Reputnub, or of Neferefre. Further north-west of the complex are mastabas built for the pharaoh's children. The tombs of the priests and officials associated with the king's funerary cult are located in the vicinity as well. Whereas the funerary cults of other kings died out in the First Intermediate Period, Nyuserre's may have survived this transitional period and into the Middle Kingdom, although this remains a contentious issue among Egyptologists.

Location and excavation[]

Nyuserre's pyramid is situated in the Abusir necropolis, between Saqqara and the Giza Plateau, in Lower Egypt (the northernmost region of Egypt).[14] Abusir was given great import in the Fifth Dynasty after Userkaf, the first ruler, built his sun temple there and his successor, Sahure, inaugurated a royal necropolis with his funerary monument.[15][16] Sahure's immediate successor and son,[16] Neferirkare Kakai, became the second king to be entombed in the necropolis.[17][18][19][20] Nyuserre's monument completed the tight architectural family unit that had grown and centered on the pyramid complex of his father, Neferirkare, alongside his mother's pyramid and brother's mastaba.[21][22][23] He was the last king to be entombed in the Abusir necropolis.[24]

Unusually, Nyuserre's mortuary complex is not seated on the Abusir-Heliopolis axis.[25][b] On taking the throne, he undertook to complete the three unfinished monuments of his father, Neferirkare; his mother, Khentkaus II; and his brother, Neferefre,[2] so their cost fell onto him.[28] To maintain the axis, Nyuserre's monument would have needed placement south-west of Neferefre's complex, deep into the desert and at least 1 km (0.62 mi) from the Nile valley.[2][28] This would have been too expensive.[28] Nyuserre may still have wanted to remain with his family[29] and so chose to insert his complex in the space north-east of Neferirkare's complex,[2] between its and Sahure's pyramids, with steep terrain to the north.[28][29] This site constrained the construction area to a region around 300 m (984 ft 3 in) square, but allowed for maximum economy of the labour force and material resources.[30] The Egyptologist Miroslav Verner succinctly describes Nyuserre's siting as "the best compromise that the circumstances would permit".[7]

In 1838, John Shae Perring, an engineer working under Colonel Howard Vyse,[31] cleared the entrances to the Sahure, Neferirkare and Nyuserre pyramids.[32] Five years later, Karl Richard Lepsius, sponsored by King Frederick William IV of Prussia,[33][34] explored the Abusir necropolis and catalogued Nyuserre's pyramid as XX.[32] From 1902 to 1908, Ludwig Borchardt, working for the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft or German Oriental Society, resurveyed the Abusir pyramids and had their adjoining temples and causeways excavated.[32][35] Borchardt's was the first, and only other, major expedition carried out at the Abusir necropolis,[35] and contributed significantly to archaeological investigation at the site.[36] His results at Nyuserre's pyramid, which he had excavated between January 1902 and April 1904,[37] are published in Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Ne-User-Re (1907).[38] The Czech Institute of Egyptology has had a long-term excavation project at Abusir since the 1960s.[35][39]

Mortuary complex[]

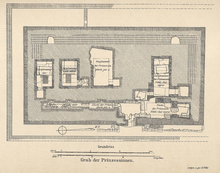

Layout[]

Old Kingdom mortuary complexes typically consist of five main components: (1) a valley temple; (2) a causeway; (3) a mortuary temple; (4) a cult pyramid; and (5) the main pyramid.[40] Nyuserre's monument has all of these elements. Its main pyramid is constructed from seven steps of limestone,[41] with a cult pyramid located near its south-east corner[42] and an unusual L-shaped mortuary temple adjacent to its eastern face.[5][42] The valley temple and causeway were originally intended for Neferirkare's monument, but were co-opted by Nyuserre.[29][43]

Main pyramid[]

Though Nyuserre reigned for around thirty years,[29] his pyramid is smaller than Neferirkare's and more comparable in size to Sahure's.[2][29] Mindful of the cost to his family, he commissioned his pyramid to lie in the only available free space not in the desert.[2] It is, therefore, positioned against the north wall of Neferirkare's mortuary temple and with the ground to the north falling steeply towards Sahure's monument.[28] It was further hemmed in by a group of mastabas to the east that had been built during Sahure's reign.[2][28][c] This combination of factors may have constricted the size of Nyuserre's pyramid.[29]

The pyramid comprises seven ascending steps, anchored on cornerstones. This was encased with fine white Tura limestone which most likely came from limestone quarries west of the village of Abusir,[41] giving it a smooth-sided finish.[46][47][48] On completion, it had a base length of 78.9 m (259 ft; 150.6 cu) sloping inwards at approximately 52° resulting in a summit height of around 52 m (171 ft; 99 cu)[5] and a total volume of approximately 113,000 m3 (148,000 cu yd).[6]

Nyuserre's pyramid, as with each of Abusir pyramids, was constructed in a drastically different manner to those of preceding dynasties. Its outer faces were framed using large – at Neferefre's unfinished pyramid the single step contained blocks up to 5 m (16 ft) by 5.5 m (18 ft) by 1 m (3.3 ft) large[49] – roughly dressed grey limestone blocks well-joined with mortar. The inner chambers were similarly framed, but using significantly smaller blocks.[50] The core of the pyramid, between the two frames, was then packed with a rubble fill of limestone chips, pottery shards, and sand, with clay mortaring.[50][49][51] This method, while less time and resource consuming, was careless and unstable, and meant that only the outer casing was constructed using high quality limestone.[52]

The chambers and mortuary temples of the Abusir pyramids were ransacked during the unrest of the First Intermediate Period, while the dismantling of the pyramids themselves took place during the New Kingdom.[53] Once the limestone casing of the pyramid was removed – for reuse in lime production[54] – the core was exposed to further human destruction and natural erosion which has left it as a ruinous, formless mound.[55] Nyuserre's monument underwent significant stone looting during the New Kingdom, during the Late Period between the Twenty-Sixth and Twenty-Seventh Dynasties, and again during the Roman era.[56]

The pyramid is surrounded by open courtyards paved with limestone blocks 0.4 m (1.3 ft) thick,[57][58] while the bricks layers can be up to 0.6 m (2.0 ft) thick.[58] Unusually, the south wing of the courtyard is significantly narrower than the north wing.[57] The enclosure wall of the pyramid courtyard was about 7.35 m (24 ft; 14 cu) high.[58]

Substructure[]

The substructure of the pyramid mimic the basic design adopted by earlier Fifth Dynasty kings.[2] It is accessed by a north–south downwards-sloping corridor whose entrance is located on the north face of the pyramid.[2][5] The corridor was lined with fine white limestone, reinforced with pink granite at both ends and follows an irregular path.[59] It is inclined up to the vestibule, where two or three large granite blocks acted as a portcullis blocking the passage when lowered.[5][59] Immediately behind, the corridor deflects to the east and is declined by about 5°.[59] It then terminates at the antechamber – connected to the burial chamber – almost directly underneath the pyramid's summit.[2][5] Damage to the interior structure caused by stone thieves makes accurate reconstruction of its architecture nigh on impossible.[59][d]

The burial- and ante- chambers and access corridor were dug out of the ground and then covered, rather than being constructed through a tunnel. The ceiling of the chambers were formed by three gabled layers of limestone beams,[41] which disperse the weight from the superstructure onto either side of the passageway preventing collapse.[61] Each stone in this structure was about 40 m3 (1,400 cu ft) in size – averaging at 9 m (30 ft) long, 2.5 m (8.2 ft) thick, and 1.75 m (5.7 ft) wide – and weighed 90 t (99 short tons).[62][29] Between each layer of blocks, limestone fragments had been used to create a filling which helped shift the weight of the structure on top of it, particularly in the event of earthquakes. This was considered to be the optimal method of roof construction at the time.[41] Stone thieves have plundered the underground chambers of much of its high-quality limestone considerably weakening the structure and making it dangerous to enter.[63] Borchardt was unable to find any fragments of interior decoration, the sarcophagus or other burial equipment in the debris-filled chambers of the substructure, much of which was rendered inaccessible by the rubble.[64] The Abusir pyramids were entered for the last time at the end of the 1960s by and , who refrained from speaking while working for fear that even the slightest vibration could cause a cave-in.[65]

Massive limestone blocks of the ceiling, compared to a worker

Rubble filled interior of the pyramid substructure

Valley temple[]

Nyuserre co-opted the valley temple and causeway that had been under construction for Neferirkare's monument.[29] As at Sahure's valley temple, there were two column adorned entrances,[66][67] though Nyuserre's columns contrast with Sahure's in that they represent papyrus stalks instead of palm trees.[68] The main entrance was on a portico which had two colonnades of four pink granite columns.[29][66][67] The second entrance, found in the west,[67] could be accessed via a staircase landing on a limestone paved portico adorned with four granite columns.[66][69] Each was shaped to resemble a six-stemmed papyrus and bore the names and titles of the king as well as images of Wadjet and Nekhbet.[66]

The temple was paved with black basalt, and had walls made from Tura limestone with relief decorated red granite dado.[68][70] Its central chamber – containing three red granite encased niches, one large and two small, in its west wall, that may have held statues of the king – held significant religious importance.[66][69] Two side rooms had black basalt dado, and the southernmost room contained a staircase leading to a roof terrace. Few remnants of the wall reliefs, such as one depicting massacres of Egypt's enemies, have been preserved. A number of statues were placed in the temple, such as one of Queen Reputnub and one of a pink granite lion.[66] The chambers preceding the causeway were angled to meet it,[71] and limestone figures of enemy captives appear to have stood at the exit of the temple at the base of the causeway.[5]

In 2009, the Czech Archaeological Mission revisited Nyuserre's valley temple and causeway to conduct trial digs at the two sites.[72] 32 m (105 ft) south of the valley temple, a north–south-oriented wall was excavated. The wall had been made from white limestone and mortared together with pink mortar.[73] The east face of the wall was found to be inclined at about 81°.[74] Indications of stone robber activity were found at the south section of the unearthed wall.[75] A combination of factors, including shape, workmanship and elevation, suggest that the excavated wall is a part of the valley temple harbour's embankment. Based on Borchardt's expeditions in combination with their 2009 findings, the Egyptologist Jaromír Krejčí estimates that the harbour was at a minimum 79 m (259 ft) long, with a potential length of around 121 m (397 ft), and a width of at least 32 m (105 ft).[69]

Causeway[]

The causeway's foundation had been laid about two-thirds of the way from the valley temple to the mortuary temple when Neferirkare died.[43] When Nyuserre took over the site, he had it diverted from its original destination to its new one.[76] As a result, the 368 m (1,207 ft) long causeway travels in one direction for more than half its length then bends away to its destination for the remainder.[5][76][77] Construction of the building was complicated because over its length it had to surmount a difference in elevation of 28 m (92 ft) and negotiate uneven terrain.[43] This elevation difference gave the structure a slope of 4°30′,[78] and required that its latter part be built with a high base.[43] Sections of this base were reused in the Twelfth Dynasty to build tombs for priests who had served Nyuserre's funerary cult.[79]

Borchardt was able to examine the causeway at its termini and at a point just east of its bend, but due to the expected costs,[80] he elected not to have it completely excavated.[81] The 2009 Czech Archaeological Mission's trial dig was conducted at a point 150 m (490 ft) west of the valley temple, and 30 m (98 ft) from where Borchardt had conducted his excavations.[81] The causeway was determined to be 7.77 m (25.5 ft) wide, with walls 2.2 m (7.2 ft) thick made of yellow core masonry encased by white limestone with mud mortaring.[82][83] Borchardt had found that its inner walls were vertically parallel, while the outer walls were declined at an angle of 75.5°.[84] The causeway had an embankment with a core made from horizontally layered yellow and grey limestone blocks that were joined primarily with grey mortar but also in parts pink mortar. The embankment core was encased with fine white limestone blocks inclined at 55° and joined together using lime mortar. Although the embankment was excavated to a depth of 10 m (33 ft) below the crown of the causeway, uncovering 12 layers of casing in total, Krejčí believes that the building's base is ~3 m (9.8 ft) deeper still. Based on the results of the excavation, Krejčí concludes that the building must have had a base at least 21 m (69 ft) wide.[85] The key finding of the dig was that causeways "represented huge, voluminous constructions".[86] Despite the efforts, the team failed to uncover any relief fragments.[85]

The causeway's interior walls were lined at the base with black basalt, above which they were lined with Tura limestone and decorated with reliefs.[5][68][83] It had a ceiling that was painted blue with a myriad of golden stars evoking the night sky.[5][83] One notable large figure relief from the causeway has been preserved. It depicts seven royal sphinxes pinning the king's enemies under their paws.[87][88]

Embankment of the causeway, after Ludwig Borchardt's excavations

Water drainage basin found at the upper end of the causeway

Relief fragment, from the causeway, depicting an enemy's head pinned under a lion's paw

Mortuary temple[]

The basic design of Nyuserre's mortuary temple differs from others built in the Fifth and Sixth Dynasty. Verner describes the layout of a typical mortuary temple for the period as resembling the letter "T" and contrasts this with the "L" shaped layout of Nyuserre's.[89] This alteration was a result of the presence of mastabas built during Sahure's reign to the east.[5][90] Despite this aesthetic difference, the temple retained all of the fundamental elements established by Sahure's mortuary temple and incorporated new features concurrently.[89]

The initial entry point to the temple is angled towards the south-east.[42] This is followed by a long entrance hall which is flanked on both the north and the south by groups of five storage rooms[91] that made up the bulk of the storage space in the temple.[68] The entrance hall was originally vaulted, had black basalt paving, and limestone walls covered in reliefs with red granite dado on the side walls.[91] Fragments of the wall reliefs from the temple are often exhibited in German museums.[89] For example, an intricate wall relief from the temple relating a scene from the throne room has been displayed at the Egyptian Museum of Berlin.[92][e] In the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty, the ruler Taharqa had reliefs from various Old Kingdom mortuary temples, particularly those of Nyuserre, Sahure and Pepi II, reproduced for use in the restoration of the temple of Kawa in Nubia.[93]

The hall terminates in a courtyard paved with black basalt and with a roofed ambulatory that was supported by sixteen six-stemmed papyrus pink granite columns.[67][91] The courtyard was designed to communicate the image of a marshy papyrus grove; a place which, for ancient Egyptians, signified renewal. To evoke this image the bases of the columns, for example, were decorated with wavy bas-reliefs which produced the illusion of papyrus growing in water. The middle portions of the columns were decorated with various inscriptions detailing material such as the king's name and titles and of the courtyard's protection by the gods Wadjet and Nekhbet.[91] These columns supported the ambulatory of the courtyard.[68] The ambulatory ceiling was decorated with stars representing the night sky of the underworld. In the centre of the courtyard was a small sandstone basin for collecting rainwater, and a highly decorated alabaster altar was once located in the north-west corner of the courtyard. The west exit of the courtyard leads into the transverse (north-south) corridor.[91]

Head of the pink granite lion, guardian of the inner temple

Painting of the mortuary temple and pyramid, by W. Büring and Th. Schinkel, as it appeared in the 3rd millennium BC

The open colonnaded courtyard of Nyuserre's mortuary temple

From the transverse corridor the temple takes a northerly direction: a result of the L-shape. In the north-west corner of the transverse corridor separating the public, outer, and intimate, inner, parts of the temple is a deep niche occupied by a large pink granite statue of a lion which served to symbolically guard the pharaoh's privacy.[94] Beyond the transverse corridor lies the chapel, which had been displaced southwards, another result of the temple shape.[67] It is damaged to the point that an accurate reconstruction cannot be made, but it is known that the chapel contained five statue niches.[91] Connected to the chapel was another group of storage rooms.[94] North of the chapel is the antichambre carrée – so named by the architect Jean-Philippe Lauer in reference to its square shape – decorated with various reliefs, an elevated floor, and a central column.[89][95] This chamber is one of two new features introduced into temple design, with this particular feature becoming a permanent element of the layout of future mortuary temples[89] until the reign of Senusret I.[94] Antecedents to the antichambre carrée have been traced to the mortuary temples of Sahure, Neferirkare, and Neferefre.[96][f] It is entered through the north wall of the five niche chapel which, with the exception of the pyramid belonging to Setibhor,[98] is the only such chamber designed to be entered from this side.[96] The floor and column base were made from limestone, and the floor was elevated by 1 cu (0.52 m; 1.7 ft), but the central column has not been preserved. The room measured 10 cu (5.2 m; 17 ft) square, with this size becoming the standard for most antichambre carrées of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties. In the north-west corner of the room, Borchardt found a fragment of a limestone statue that had been fixed to the floor using mortar.[99] Borchardt also found several fragments of relief decorations nearby which may have originated in the room. These fragments depicted anthropomorphised deities with animal heads including Sobek, Horus, and three deities (one with a human head) which possessed was-sceptres and ankh symbols.[100]

(1) Beloved of Nekhbet, given life, health

(2) Give enduring life to Nyuserre, king of Upper and Lower Egypt

(3) Life, stability, and prosperity for the favourite of the Two Lands of Egypt[g]

(4) The favourite of the Two Ladies, Nekhbet and Wadjet,[h] the Divine Golden Falcon,[i] may he live forever

The antichambre carrée leads into the sacrificial, or offering, hall via a vestibule[89][95] which was left out in later renditions.[99] The offering hall was set along the east–west axis for religious reasons,[j] and located in its traditional place in the centre of the east face of, and adjoining, the main pyramid. The offering hall an altar for performing ritual sacrifices and had a false granite door.[5][94] As with the entrance hall, the walls of the offering hall were decorated with reliefs; these depicted scenes related to the ritual sacrifices performed there.[95] Similarly to the ambulatory of the courtyard, the vaulted ceiling of the hall was decorated with bas-relief stars evoking the night sky of the underworld. Under the east wall was a canal connected to a drainage system east of the temple. North of the offering hall were a final group of storage rooms.[94] Lastly, there is an alternate entrance point that sits near the intersection between the outer and inner sanctuaries that can be accessed from the outside.[89]

The mortuary temple displays two other significant innovations.[94] One architectural modification can be found incorporated into the design of the temple and has had a marked influence on ancient Egyptian architecture. Tall tower-shaped buildings with slight slopes were erected on the north- and south-east corners of the temple. The tops of these towers formed a flat terrace, topped with a concave cornice, which could be accessed via staircase.[94][113] Verner refers to these towers as the "prototype of pylons" which became staple features of later ancient Egyptian temples and palaces.[114] The second addition is more complex and, as yet, unexplained. In the north-east corner of the temple, adjoining the wall, Borchardt discovered a square platform with sides approximately 10 m (33 ft) in length.[43] Excavations by a Czech team at the mastaba of Ptahshepses', the vizier to the pharaoh and head of all royal works,[35][115] discovered a large pink granite pyramidion, taken from an obelisk, resting next to a similar square platform in the south-western corner.[43] Verner proposes several hypotheses for the purpose of the square platform in Nyuserre's mortuary temple: (1) The square platform may once have been occupied by a similar pyramidion; evidence supporting this conjecture are a large granite obelisk found in the pyramid complex – obelisks were the architectonic midpoints of sun temples, but not found in mortuary temples, making this discovery unique – and stone blocks containing the inscription "Sahure's sacrifice field".[116][k] (2) The blocks could either be remnants of the building material used for Sahure's sun temple, or, be taken from the sun temple itself. This led to conjecture (3) that the sun temple may be located near Nyuserre's complex and/or (4) that Nyuserre may have either dismantled or usurped the sun temple for himself.[43]

Cult pyramid[]

Borchardt erroneously ascribed the structure found in the south-east corner of the complex to Nyuserre's consort; it was, in fact, the cult pyramid.[59] The pyramid has its own enclosure and bears the standard T-shaped substructure of passage and chambers.[5] It had a base length of approximately 15.5 m (51 ft; 29.6 cu) and a peak approximately 10.5 m (34 ft; 20.0 cu) high.[117]

The pyramid's single chamber was built by digging a pit into the ground. The walls of the chamber were made from yellow limestone and joined with mortar. The entrance leading to the chamber was cut at an oblique angle, partly recessed into the masonry and partly sunk into the ground. Very little of the interior structure has been preserved, and near none of the chamber's white limestone casing retained, save for a single block found in the south-west corner of the chamber.[118]

The purpose of the cult pyramid remains unclear. It had a burial chamber but was not used for burials, and instead appears to have been a purely symbolic structure.[119] It may have hosted the pharaoh's ka (spirit),[102] or a miniature statue of the king.[120] It may have been used for ritual performances centering around the burial and resurrection of the ka spirit during the Sed festival.[120]

Other significant structures[]

Conjectural: wives' tombs[]

Nyuserre's wife, Reputnub, was not buried within the pyramid complex of Nyuserre.[17] Two small pyramids found on the southern margin of the pyramid cluster, designated Lepsius XXIV and Lepsius XXV, are conjectured to belong to his consorts. These structures are very badly damaged, and Verner expects that no exceptional finds will be made during excavations.[114]

The first of these pyramids, Lepsius XXIV, consisted of the pyramid, mortuary temple and small cult pyramid.[115] Extensive damage to the tomb's structure,[121] due to stone thieves in the New Kingdom, has left the structure in ruins, though some details can be discerned.[122] The mortuary temple was built on the east face of the pyramid, confirming that the tomb belonged to a queen. Its destruction has laid the interior bare for archaeologists to study. The pyramid was constructed during Nyuserre's reign, as evidenced by Ptahshepses' name[l] appearing on blocks amidst many other masons' marks and inscriptions.[124] Inside the wreckage of the burial chamber lie the remnants of a pink granite sarcophagus, shards of pottery, and the mummified remains of a young woman, between twenty-one and twenty-five years of age.[115][125]

The mummy is fragmented, likely due to the activities of tomb robbers and stone thieves.[125] Her name was not found inscribed anywhere in the complex, leaving the mummy remains unidentified. Dating suggests that the mummy was either the consort to Nyuserre, or possibly, to his short lived pharaoh brother, Neferefre.[115] Queen Reputnub is a potential candidate for the identity of the mummy, though the possibility of other wives remains feasible.[126] Unusually, this mummy has undergone excerebration,[m] a procedure which Verner states was not known to have been conducted prior to the Middle Kingdom.[122] Professors Eugen Strouhal, Viktor Černý, and Luboš Vyhnánek challenge this, stating that some mummies from the Eighth Dynasty and one from the Sixth Dynasty are confirmed to have undergone the procedure.[127]

The sister tomb, Lepsius XXV, is in close proximity to Lepsius XXIV. A superficial study of the tomb revealed that it was built during Nyuserre's reign.[115] Excavations were conducted by Verner's archaeological team between 2001 and 2004.[128] Verner had originally believed that the mortuary temple for this tomb was built on the western face of the pyramid, instead of the usual eastern one.[115] His later excavations revealed that the pyramid lacked a mortuary temple altogether. It was revealed that the monument consisted of two pyramid tombs placed adjacent to each other. Both tombs are oblong shaped, though the eastern tomb is larger than the western one. The tombs are oriented along a north–south axis. The owners and relations of these tombs remain unknown.[128]

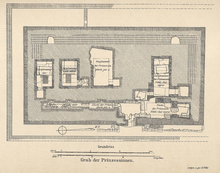

Mastaba of the Princesses[]

To the north-west of Nyuserre's pyramid is a tomb constructed for three of the ruler's children,[3] which was identified by Borchardt as the "Mastaba of the Princesses".[114] The superstructure of this tomb was constructed by packing rubble to create a thick wall, and enclosing it with yellow limestone blocks, with its facade further encased with fine white limestone. This valuable outer layer has been stripped, with only a fragment of it left on the doorway. Despite this, the layout of the tomb – with its four burial chambers and cult rooms[129] – has been well preserved.[130]

The false doors of the burial chambers are the only decorative remnants found, though Borchardt speculates that these might have been the only ornamentation to begin with. Within the cult rooms, traces of red paint had survived, indicating that the walls were decorated to imitate granite. The northernmost false door bears the titles of Khamerernebty, a daughter of king Nyuserre, and a priestess of Hathor.[131] The second false door bears the name of Meritjots. It too contains inscriptions and a carving of the subject, but is of inferior craftsmanship. Fragments of paint retained indicate that the block was painted red to imitate granite, whilst the carved writings were painted green. The third false door was left entirely blank, whilst the last false door, which is similar to the second, is inscribed only on the lintel, and bears the name of Kahotep.[132]

False door of Khamerernebty,

False door of Khamerernebty,

bearing her titles and image

Drawing, by O. Völz, of the layout of the "Mastaba of the Princesses"

Round lintel from the false door of Kahotep,

Round lintel from the false door of Kahotep,

bearing his name

Later history[]

Nyuserre was the last king to build his funerary monument at Abusir. His successors Menkauhor, Djedkare Isesi and Unas chose to be buried elsewhere,[35][133][134] and Abusir ceased to be the royal necropolis.[135]

Funerary cult[]

The Abusir Papyri record evidence indicating that the funerary cults at Abusir remained active at least until the reign of Pepi II in the late Sixth Dynasty.[133] The continuation of these cults in the period following the Old Kingdom; however, is a matter of significant debate among Egyptologists.[136] Verner believes that these cults ceased activities by the First Intermediate Period.[35] He argues that the reunification of Egypt and subsequent stabilization at the end of the Eleventh Dynasty allowed the mortuary cults of Abusir to reform temporarily before soon dying out permanently.[137] Jaromír Málek draws a distinction between surviving estates, which form the economic foundation of the funerary cult, and survival of the cult itself, and notes that reliable evidence for the continuation of these cults is absent, except for the cults of Teti and, possibly, Nyuserre.[138] Ladislav Bareš suggests that only Nyuserre's cult persisted through the period, albeit in a very reduced form.[139] Antonio Morales considers two forms of cultic activities, the official royal cult and popular veneration of the king, and believes that in the case of Nyuserre both forms of cultic worship survived the transition from the Old Kingdom, throughout First Intermediate Period, and into the early Middle Kingdom.[140] He argues that archaeological trace evidence found near Nyuserre's monument – such as tombs found east of the mortuary temple dated to the First Intermediate Period and Middle Kingdom which may be associated with the royal cult through onomastica, titles, and other textual writings;[141] the writings on the false door of Ipi, dated to the First Intermediate Period, bearing Nyuserre's birth name; and an inscribed block belonging to an overseer in the nearby pyramid town of Neferirkare, found by the alternate entrance to the mortuary temple[142] – support the survival of cultic activity honouring Nyuserre from the Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom.[143] Restoration work to the pavement of Nyuserre's mortuary temple, and an inscription from an anonymous ruler dating to the end of the Old Kingdom are further indicators of activity at the funerary monument.[144]

The tombs of two estate chiefs and overseers of the mortuary temple, Heryshefhetep I and II,[n] may serve as evidence for the continuity for Nyuserre's cult. The tombs of these two officials are given plausible dates between the Ninth and Tenth Dynasties – the Herakleopolitan period[146] – or the Eleventh Dynasty.[147][148] If the two priests lived during the Herakleopolitan period, then that would indicate that Nyuserre's funerary cult and the estates of his pyramid were functioning and intact during the First Intermediate Period.[149] Moreover, if this is the case, then Nyuserre's cult survived through to at least the Twelfth Dynasty, under the priest Inhetep.[147][o] The false door from the tomb of a female[151] priest or official, Satimpi,[p] found near the causeway, may also be dated to the First Intermediate Period. The burial of priests in this period may be another indicator for the maintenance of his cult.[152]

Burials[]

From the end of Nyuserre's reign through to the Middle Kingdom, the areas around his monument's causeway and mortuary temple[154] became home to other tombs.[133] Djedkare Isesi buried various members of his family and officials on the slope south-east of the mortuary temple.[135] The members of the royal family buried there are Khekeretnebty with her daughter Tisethor, Hedjetnebu, and Neserkauhor, along with the officials Mernefu, Idut and Khenit. There is also a tomb whose owner remains unidentified.[155] This cemetery gradually expanded east toward the edge of the Nile valley, reaching its peak in the Sixth Dynasty, but Abusir was being used only as a local cemetery by this time.[156] Many of the tombs discovered here belong to employees of the mortuary cult, such as those of Fetekta and Hetepi who administered the stores.[157]

South-east of the mortuary temple lies the tomb of Inemakhet and Inhetep (I).[q] Inside, an inscription reading "honored before Osiris, lord of life, and Iny, lord of reverence" was discovered on some funerary equipment. Two other tombs bearing similar names, those of Inhetep (II) and Inhetepi,[r] are also in the area.[158] The venerated status of Nyuserre is evidenced in the onomastica of these buried individuals who took their names from Nyuserre's birth name, Ini.[159][160]

To the north of Nyuserre's monument is a cemetery split into two regions. The northwestern sector contains tombs built at the end of Nyuserre's reign. The northeastern sector, located just north of the mortuary temple, established between the First Intermediate Period and early Middle Kingdom,[141][161] contains tombs of individuals associated with the funerary cult of the king.[141] Other tombs of the priests of Nyuserre's cult are concentrated around the eastern facade of the mortuary temple and at the upper end of the causeway.[139]

The monument site was used for occasional burials in the Late Period.[133] East of the mortuary temple, German Egyptologists unearthed thirty-one Greek burials dated between c. 375–350 BC, from 1901 to 1904.[162] This dating is in dispute, and an alternate view argues that the tombs were built after Alexander the Great's conquest of Egypt. According to Verner, the construction of these tombs mark the end of the history of the Abusir cemetery.[163]

See also[]

- List of Egyptian pyramids

- List of megalithic sites

Notes[]

- ^ Proposed dates for Nyuserre's reign: c. 2474–2444 BC,[7] c. 2470–2440 BC,[3] c. 2453–2422 BC,[8] c. 2445–2421 BC,[9][10] c. 2420–2389 BC,[11] c. 2416–2388 BC,[12] c. 2359–2348 BC.[13]

- ^ The Abusir-Heliopolis axis is a figurative line connecting the north-west corners of the pyramids of Neferirkare, Sahure, Neferefre and Heliopolis.[26][27]

- ^ The dating of the mastaba belonging to Userkafankh to Sahure's reign is not unanimous. The historian Nigel Strudwick notes that if Userkafankh (transl. ˀnh-wsr-k3f) was born during the reign of Userkaf, as his namesake suggests, he would not have held office until at least Neferirkare's reign.[44] The Egyptologist Jaromír Krejčí references reliefs in Nyuserre's mortuary temple bearing the name Userkafankh and the design and architecture of his tomb as strong indicators that the tomb was built at a later date.[45]

- ^ The destruction of the substructure is so substantial that Borchardt assumed for "Schönheitsrücksichten" (aesthetic considerations) the existence of the "Vorkammer" (antechamber) to explain the change in direction of the corridor, noting that "Wie die Aufnahme zeigt, konnten wir von dieser Kammer nichts sehen" (as shown in the image, we could see nothing of this chamber).[60]

- ^ Äegyptiches Museum und Papyrussammlung[92]

- ^ Sahure and Neferirkare's pyramids had a rectangular room preceding the offering hall, while in Neferefre's a small square chamber was discovered during excavations.[97]

- ^ Setib-tawy is Nyuserre's Horus name meaning "The favourite of the Two Lands".[101]

- ^ Setib-Nebty is Nyuserre's Nebty name translating to "The favourite of the Two Ladies".[101]

- ^ Bik-Nebu-Netjeri is Nyuserre's Golden Horus name meaning "The Divine Golden Falcon".[101]

- ^ The mortuary temple functioned as a symbolic resting place for the pharaoh. Here, priests tending to cult performed daily rituals and processions for the god king.[102] It was believed that when an individual died, their ka, ba and body became separated. The ka, which can be approximated to mean life force, was sustained with food, hence the food offerings in the offering hall. This was the most significant room in the temple.[103][104] The ba, which can be approximated to a soul, is the individual which travels into the afterlife in search of the ka. The body itself becomes inanimate, but must not decay or else the ba will be unable to function.[105] In the afterlife, when the parts reunited, the individual became an akh, the approximate equivalent to a ghost, representing the resurrected form of the king.[106] The pyramid was an instrument which enabled this union to happen.[107] As an akh, the king was free to roam the earth and the sky, and became second only to the gods. The purpose of the burial rites and offerings was to allow the akh to form.[106] The king would pass through the false door, have his meal, and then return to his tomb.[108] The food was not physically eaten, rather, it was a token of a meal shared between the living in this world, and the deceased in the next.[109] The corridor leading to the chambers in the pyramid served twin functions: first, to allow passage into the pyramid for the burial, and second, to allow the resurrected king to leave. From the king's perspective, the corridor ascended into the region of the sky in the north referred to as "the Imperishable Ones" where the king united with the goddess of the sky Nut. Nut ate the sun at sunset and gave birth to it at sunrise. In effect, she would do the same for the king, transforming him into a sun god.[110][111] For this reason, the complex took on an east-west orientation, mirroring the sun's path through the sky.[112]

- ^ "Sahure's sacrifice field" is the name of Sahure's sun temple.[116]

- ^ Ptahshepses' had been the overseer of all the works in the royal necropolis of Abusir. He had his own tomb constructed at a point near equidistant from Sahure's and Nyuserre's pyramids, a deliberate selection.[123]

- ^ A procedure to remove the brain through the nasal septum.[115]

- ^ transl. Ḥry–š.f–ḥtp[145]

- ^ transl. 'In–ḥtp[150]

- ^ transl. Sʒ.t–jmpj[152] or Sʒt-impy[153]

- ^ transl. Jn–m–ʒḫ.t and Jn-ḥtp[158]

- ^ transl. Jn–ḥtp and Jn–ḥtpj[158]

References[]

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Verner 1994, p. 80.

- ^ a b c Altenmüller 2001, p. 599.

- ^ Grimal 1992, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Lehner 2008, p. 149.

- ^ a b Bárta 2005, p. 180.

- ^ a b c Verner 2001c, p. 589.

- ^ Clayton 1994, p. 30.

- ^ Shaw 2003, p. 482.

- ^ Málek 2003, p. 100.

- ^ Allen et al. 1999, p. xx.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 288.

- ^ Arnold 2003, p. 3.

- ^ Verner 2001b, p. 5.

- ^ a b Bárta 2017, p. 6.

- ^ a b Verner 2001b, p. 6.

- ^ Verner 2001d, p. 302.

- ^ Dodson 2016, p. 27.

- ^ Bárta 2015, Abusir in the Third Millennium BC.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 77, 79–80.

- ^ Verner 2002, p. 54.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 145.

- ^ Bárta 2017, p. 8.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 79–80.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 135.

- ^ Isler 2001, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d e f Verner 2001d, p. 311.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lehner 2008, p. 148.

- ^ Verner 2001a, p. 396.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 50.

- ^ a b c Edwards 1999, p. 97.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 54.

- ^ Peck 2001, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f Verner 2001b, p. 7.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 105, 215–217.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 215.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, Titelblatt & Inhaltsverzeichnis.

- ^ Krejčí 2015, Térenní projekty: Abúsír.

- ^ Bárta 2005, p. 178.

- ^ a b c d Verner 2001d, p. 312.

- ^ a b c Verner 2001d, p. 314.

- ^ a b c d e f g Verner 2001d, p. 318.

- ^ Strudwick 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Krejčí 2000, p. 475.

- ^ Gros de Beler 2000, p. 119.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 149 image.

- ^ Bard 2015, General statement about pyramids on p. 145.

- ^ a b Verner 2001d, p. 97.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, p. 139.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 15.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 140.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 89.

- ^ Edwards 1975, p. 178.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 73, 139–140.

- ^ Bareš 2000, pp. 10, 13–14.

- ^ a b Verner 2001d, pp. 312–313.

- ^ a b c Borchardt 1907, p. 96.

- ^ a b c d e Verner 2001d, p. 313.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, pp. 101–102.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 144.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. 103.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 81.

- ^ a b c d e f Verner 2001d, p. 319.

- ^ a b c d e Arnold 2003, p. 163.

- ^ a b c d e Edwards 1975, p. 187.

- ^ a b c Krejčí 2011, p. 517.

- ^ Lehner 2008, pp. 149–150.

- ^ Wilkinson 2000, p. 123.

- ^ Krejčí 2011, p. 513.

- ^ Krejčí 2011, p. 514.

- ^ Krejčí 2011, pp. 514–515.

- ^ Krejčí 2011, p. 515.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Verner 2001d, pp. 318, 464.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. 44.

- ^ Verner 2001d, pp. 318–319.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, pp. 42–43.

- ^ a b Krejčí 2011, p. 520.

- ^ Krejčí 2011, p. 521.

- ^ a b c Borchardt 1907, p. 45.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. 43.

- ^ a b Krejčí 2011, p. 522.

- ^ Krejčí 2011, p. 524.

- ^ Allen et al. 1999, p. 92.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, pp. 46–49, Fig. 29, p. 46, Fig. 31, p. 48, Blatt 8–12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Verner 1994, p. 82.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 80, 82.

- ^ a b c d e f Verner 2001d, p. 315.

- ^ a b Allen et al. 1999, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Grimal 1992, pp. 347–348, 394.

- ^ a b c d e f g Verner 2001d, p. 316.

- ^ a b c Verner 2001d, pp. 315–316.

- ^ a b Megahed 2016, p. 240.

- ^ Megahed 2016, pp. 240–241.

- ^ CEGU 2019, Discovery of a unique tomb and the name of an ancient Egyptian queen in south Saqqara.

- ^ a b Megahed 2016, p. 241.

- ^ Megahed 2016, pp. 241–242.

- ^ a b c Leprohon 2013, p. 40.

- ^ a b Lehner 2008, p. 18.

- ^ Lehner 2008, pp. 23, 28.

- ^ Verner 2001d, p. 52.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 23.

- ^ a b Lehner 2008, p. 24.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 20.

- ^ Verner 2001d, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Lehner 2008, p. 28.

- ^ Lehner 2008, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Verner 2001d, p. 36.

- ^ Verner 2001d, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 82–83.

- ^ a b c Verner 1994, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f g Verner 2001d, p. 321.

- ^ a b Verner 2001d, pp. 316, 318.

- ^ Verner 2001d, p. 464.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Verner 2001d, p. 53.

- ^ a b Arnold 2005, p. 70.

- ^ Strouhal, Černý & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 543.

- ^ a b Verner 2001d, pp. 320–321.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 178.

- ^ Verner 2001d, p. 320.

- ^ a b Strouhal, Černý & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 544.

- ^ Strouhal, Černý & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 550.

- ^ Strouhal, Černý & Vyhnánek 2000, p. 549.

- ^ a b Verner 2007, p. 8.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. Blatt 25.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. 126.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. 127.

- ^ Borchardt 1907, p. 128.

- ^ a b c d Goelet 1999, p. 87.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 19, 80, 86.

- ^ a b Verner 1994, p. 86.

- ^ Morales 2006, p. 311.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Málek 2000, pp. 244–245.

- ^ a b Bareš 2000, p. 5.

- ^ Morales 2006, pp. 312–314.

- ^ a b c Morales 2006, pp. 325–326.

- ^ Morales 2006, pp. 317–318.

- ^ Morales 2006, pp. 314–316.

- ^ Bareš 2000, pp. 2–3.

- ^ Málek 2000, p. 245.

- ^ Bard 2015, p. 38.

- ^ a b Málek 2000, pp. 245–246, 248.

- ^ Morales 2006, pp. 327, 336.

- ^ Morales 2006, p. 336.

- ^ Málek 2000, p. 248.

- ^ Daoud 2000, p. 203.

- ^ a b Morales 2006, p. 329.

- ^ Daoud 2000, p. 202.

- ^ Morales 2006, p. 324.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 82, 86.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 87.

- ^ Verner 1994, pp. 87–89.

- ^ a b c Morales 2006, p. 326.

- ^ Daoud 2000, p. 199.

- ^ Morales 2006, p. 337.

- ^ Daoud 2000, pp. 194–195.

- ^ Smoláriková 2000, p. 68.

- ^ Verner 1994, p. 96.

Sources[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramid of Nyuserre Ini. |

- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; et al. (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6543-0. OCLC 41431623.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Arnold, Dieter (2003). The Encyclopaedia of Ancient Egyptian Architecture. London: I.B Tauris & Co Ltd. ISBN 1-86064-465-1.

- Arnold, Dieter (2005). "Royal cult complexes of the Old and Middle Kingdoms". In Schafer, Byron E. (ed.). Temples of Ancient Egypt. London, New York: I.B. Taurus. pp. 31–86. ISBN 978-1-85043-945-5.

- Bard, Kathryn (2015). An Introduction to the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-89611-2.

- Bareš, Ladislav (2000). "The destruction of the monuments at the necropolis of Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 1–16. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2005). "Location of the Old Kingdom Pyramids in Egypt" (PDF). Cambridge Archaeological Journal. Cambridge. 15 (2): 177–191. doi:10.1017/s0959774305000090. S2CID 161629772. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-02-28.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2015). "Abusir in the Third Millennium BC". CEGU FF. Český egyptologický ústav. Retrieved 1 February 2018.

- Bárta, Miroslav (2017). "Radjedef to the Eighth Dynasty". UCLA Encyclopedia of Egyptology.

- Borchardt, Ludwig (1907). Das Grabdenkmal des Königs Ne-User-Re. Ausgrabungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft in Abusir; 1 : Wissenschaftliche Veröffentlichungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft; 7 (in German). Leipzig: Hinrichs. doi:10.11588/diglit.36919. OCLC 557849948.

- Clayton, Peter A. (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Daoud, Khaled A. (2000). "Abusir during the Herakleopolitan Period". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 193–206. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- "Discovery of a unique tomb and the name of an ancient Egyptian queen in south Saqqara". Czech Institute of Egyptology. 2019-04-02. Retrieved 23 April 2019.

- Dodson, Aidan (2016). The Royal Tombs of Ancient Egypt. Barnsley, South Yorkshire: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-4738-2159-0.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05128-3.

- Edwards, Iorwerth (1975). The pyramids of Egypt. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-020168-0.

- Edwards, Iorwerth (1999). "Abusir". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. pp. 97–99. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Goelet, Ogden (1999). "Abu Ghurab/Abusir after the 5th Dynasty". In Bard, Kathryn (ed.). Encyclopedia of the archaeology of ancient Egypt. London; New York: Routledge. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-203-98283-9.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Gros de Beler, Aude (2000). The Nile. Paris: Molière Editions. ISBN 978-2907670333.

- Isler, Martin (2001). Sticks, Stones, and Shadows: Building the Egyptian Pyramids. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3342-3.

- Krejčí, Jaromír (2000). "The origins and development of the royal necropolis at Abusir in the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 467–484. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Krejčí, Jaromír (2011). "Nyuserra revisited". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010. Vol. 1. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University. pp. 513–524. ISBN 978-80-73083-84-7.

- Krejčí, Jaromír (2015). "Abúsír". CEGU FF (in Czech). Český egyptologický ústav. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28547-3.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The Great Name: Ancient Egyptian Royal Titulary. Vol. Volume 33 of Writings from the ancient world. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

{{cite book}}:|volume=has extra text (help) - Málek, Jaromír (2000). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 241–258. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Málek, Jaromír (2003). "The Old Kingdom (c. 2686–2160 BC)". In Shaw, Ian (ed.). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 83–107. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Megahed, Mohamed (2016). "The antichambre carée in the Old Kingdom. Decoration and function". In Landgráfová, Renata; Mynářová, Jana (eds.). Rich and great: studies in honour of Anthony J. Spalinger on the occasion of his 70th Feast of Thoth. Prague: Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts. pp. 239–259. ISBN 978-8073086688.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27 – July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.

- Peck, William H. (2001). "Lepsius, Karl Richard". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 289–290. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Shaw, Ian, ed. (2003). The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Smoláriková, Květa (2000). "The Greek cemetery in Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 67–72. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Strouhal, Eugen; Černý, Viktor; Vyhnánek, Luboš (2000). "An X-ray examination of the mummy found in pyramid Lepsius No. XXIV at Abusir". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír (eds.). Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 543–550. ISBN 80-85425-39-4.

- Strudwick, Nigel (2005). Leprohon, Ronald (ed.). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-13048-7.

- Verner, Miroslav (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. Prague. 69 (3): 363–418. ISSN 0044-8699.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Abusir". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001c). "Old Kingdom". In Redford, Donald B. (ed.). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001d). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 978-0-8021-1703-8.

- Verner, Miroslav (2002). Abusir: Realm of Osiris. Cairo; New York: American Univ in Cairo Press. ISBN 977424723X.

- Verner, Miroslav (2007). "New Archeological Discoveries in the Abusir Pyramid Field". Archaeogate. Archived from the original on 2009-01-30. Retrieved 5 February 2018.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. (2000). The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05100-9.

- 3rd-millennium BC establishments in Egypt

- Abusir

- Buildings and structures completed in the 25th century BC

- Pyramids of the Fifth Dynasty of Egypt