Questing Beast

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2009) |

The Questing Beast, or the Beast Glatisant (Old French: beste glatisant, Modern French: bête glatissante), is a cross-animal monster appearing in many medieval texts of Arthurian legend and modern works inspired by them. In the French prose cycles, and consequently in the quasi-canon of Le Morte d'Arthur, the hunt for the Beast is the subject of quests futilely undertaken by King Pellinore and his family and finally achieved by Sir Palamedes and his companions.

Description and name[]

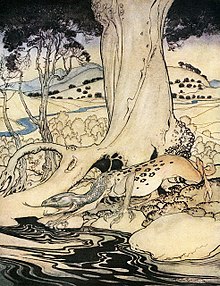

The strange creature has the head and neck of a snake, the body of a leopard, the haunches of a lion, and the feet of a hart.[1] Its name comes from the great noise that it emits from its belly, a barking like "thirty couple hounds questing". Glatisant is related to the French word glapissant, 'yelping' or 'barking', especially of small dogs or foxes. The questing beast is a variant of the medieval mythological view on giraffes, whose generic name of Camelopardalis originated from their description of being half-camel and half-leopard.[2]

In medieval literature[]

The account from Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin, which was taken up by Thomas Malory for his seminal Le Morte d'Arthur, has the Beast appear to the young King Arthur after he has had an affair with his half-sister Morgause and begotten Mordred (they did not know that they were related when the incestuous act occurred). Arthur sees the beast drinking from a pool just after he wakes from a disturbing dream that foretells Mordred's destruction of the realm. He is then approached by King Pellinore, who confides that it is his family quest to hunt the beast. Merlin reveals that the Beast had been born of a human woman, a princess who lusted after her own brother. She slept with a devil who had promised to make the boy love her, but the devil manipulated her into accusing her brother of rape. Their father had the brother torn apart by dogs as punishment. Before he died, however, he prophesied that his sister would give birth to an abomination that would make the same sounds as the pack of dogs that were about to kill him. Later on in the Post-Vulgate, the Prose Tristan, and the sections of Malory based on those works, Saracen knight Palamedes hunts the Beast. It is at first a futile venture, much like his love for Tristan's paramour Iseult, offering him nothing but hardship. But his conversion to Christianity allows Palamedes relief from his endless worldly pursuits, and he finally slays the creature during the Grail Quest after he, Percival, and Galahad have chased it into a lake. The Beast's story can be interpreted as a symbol of the incest, violence and chaos that eventually destroys Arthur's kingdom.

The earlier Perlesvaus, however, offers an entirely different depiction of the Beast than the best known one, given above. There, it is described as pure white, smaller than a fox, and beautiful to look at. The noise from its belly is the sound of its offspring who tear the creature apart from the inside; the author takes the beast as a symbol of Christ, destroyed by the followers of the Old Law, the Twelve Tribes of Israel. Gerbert de Montreuil provides a similar vision of the Beast in his Continuation of Perceval, the Story of the Grail, though he says that it is "wondrously large" and interprets the noise and subsequent gruesome death by its own offspring as a symbol of impious churchgoers who disturb the sanctity of Mass by talking. The Beast appears in some other works as well, including stories written in French, Galician, Spanish, and Italian.

Modern versions[]

- T. H. White re-envisions the Questing Beast's role in his novel The Once and Future King. As King Pellinore describes it, the hunt of the Beast has always been the burden of the Pellinores, and all Pellinores are in fact trained for the hunt from birth—a training which does not seem to extend much beyond finding the Beast's fewmets. (Pellinore is more of a comic character as described by White than a great hunter or knight.) Having searched fruitlessly all his life for the Beast, Pellinore is convinced by his friend Sir Grummore Grummursum to drop his quest. However, it turns out later that the beast is pining away for lack of attention, so King Pellinore nurses it back to health and resumes his Sisyphean hunt. This account also appears in slightly different form in the original version of The Sword in the Stone. There, King Pellinore is imprisoned by Galapas the giant, but he is saved by the Beast who turns up to rescue him—as well as Merlin and Arthur, who happen to be there at the time. Galapas ends up barricaded in his topmost tower, shrieking "let go of me you awful animal", and shouting to be rescued by the Fire Brigade. Later, the Beast falls in love with Sir Palomides, who briefly disguised himself and Sir Grummore as the beast herself in order to raise Pellinore's spirits when he is pining for his lover. White explains that this is why it is Palomides who is seen pursuing the beast later in Malory's work.

- A 1967 television episode of Lost in Space features the Questing Beast pursued by Sir Sagramonte.

- The Questing Beast appears in "Le Morte d'Arthur", the first season finale of the BBC's series Merlin.[3]

- The Questing Beast also appears in the Thursday Next novel series by Jasper Fforde, although it is not described. Here it is also hunted by King Pellinore as part of his family's tradition and burden.

- A Questing Beast appears in the novel and subsequent TV series The Magicians, but this beast is instead a reference to the White Stag from The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe.

- The Arthurian-inspired Magic: The Gathering set Throne of Eldraine features a card named Questing Beast, based on the legend of the same name.

- The InCryptid series by Seanan McGuire features a North American version with the head and tail of a rattlesnake, and the body of a mountain lion.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Arthurian Legend - Monsters". Uiweb.uidaho.edu. Archived from the original on 2013-11-09. Retrieved 2014-06-14.

- ^ "Caesar's giraffe". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2021-06-02.

- ^ "Le Morte d'Arthur, Series 1, Merlin - BBC One". BBC. Retrieved 4 March 2018.

External links[]

- Arthurian legend

- Mythological hybrids

- European legendary creatures