Raphèl mai amècche zabì almi

"Raphèl mai amècche zabì almi" is a verse from Dante's Inferno, XXXI.67. The verse is shouted out by Nimrod, one of the giants who guard the Ninth Circle of Hell. The line, whose literal meaning is uncertain (it is usually left untranslated as well), is usually interpreted as a sign of the confusion of the languages caused by the fall of the Tower of Babel.

Context and content[]

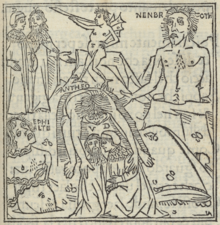

The biblical character Nimrod is portrayed as a giant in the Inferno, congruent with medieval traditions of giants.[1] That he is the biblical character also is indicated by the hunter's horn which hangs across his chest: Nimrod is "a mighty hunter before God" (Genesis 10:9). With other mythological giants, Nimrod forms a ring surrounding the central pit of Hell, a ring that Dante from a distance mistakes as a series of towers which he compares to those of Monteriggioni (40–45). When Nimrod speaks this, his only line in the poem, Virgil explains that "every language is to him the same / as his to others—no one knows his tongue" (80–81).

Interpretation[]

Early commentators of Dante generally agreed already that there was no possible translation.[2] Critics have noted, though, that there are possible comparisons with magic formulae, "with their mixtures of Hebrew-, Greek-, and Latin-looking words, and suggestions of angelic and demoniac names." Such formulae were often interspersed with psalms—Nimrod's line ends with almi, and its rhyme word in line 69 is salmi, "psalms".[3]

Later critics typically read the "senseless"[4] verse as a sign of incomprehensibility, of the tendency of poetic language to "displace language from the register of its ordinary operation".[5] The line is compared to Papé Satàn, papé Satàn aleppe, another untranslatable verse from the Inferno (VII.1) spoken by an angry demon[3] (Plutus), both of which are, according to one critic, "intended primarily to represent the mental confusion brought about by the sin of pride."[6]

Denis Donoghue warns, however, that Virgil may be too quick with his criticism: "Virgil is not a patient critic, though his morality is impressive; he should have attended to the fury in Nimrod's words, if it is fury, and not to the words." Rather than "gibberish", Donoghue suggests it is "probably another version of King Lear's 'matter and impertinency mixed, reason in madness.'"[7][8] Eric Rabkin reads the line as an example of metalinguistic discourse (which treats "language as subject, material, [and] context"):

In saying "'He hath himself accused,'" Virgil is making Nimrod's language the subject of his own language; in creating this nonsense utterance, the poet Dante is using language as material to be shaped into his poem; and in having the incomprehensible statement made meaningful to Dante by his mentor-poet Virgil, the text elliptically comments on its own context, on its existence as poetry that has the effect of creating order and palpable reality even where such reality may to ordinary or unblessed mortals be unapparent.[9]

Literary historian László Szörényi considers Nimrod speaks Old Hungarian, which, after philological examinations, can be interpreted to the line Rabhel maj, amék szabi állni (modern: Rabhely majd, amelyek szabja állni), roughly in English "It's a jail that forces you to stay here!". It is not clear whether Nimrod speaks this sentence to threaten Virgil and Dante or to express his own miserable fate. Szörényi points out that Nimrod appears as the forefather of the Hungarians in Simon of Kéza's Gesta Hunnorum et Hungarorum. Dante was a friend of Charles Martel of Anjou, pretender to the Hungarian throne, who was surrounded by Hungarian courtiers and clergymen. There Dante perhaps became familiar with the Hungarian chronicle tradition.[10]

References[]

- ^ Alighieri, Dante; Björkesson, Ingvar (2006). Den gudomliga komedin (Divine Comedy), comments by Ingvar Björkesson. www.nok.se. Levande Litteratur (in Swedish). Natur & Kultur. p. 425. ISBN 978-91-27-11468-5.

- ^ Mandelbaum, Allen (2004). The Divine Comedy of Dante Alighieri: Inferno. Bantam. pp. 387–88. ISBN 978-0-553-21339-3.

- ^ a b Austin, H.D. (1940). "Notes to the Divine Comedy (A Supplement to Existing Commentaries)". PMLA. 55 (33): 660–713. doi:10.2307/458732. JSTOR 458732.

- ^ Kleiner, John (1998). "Mismapping the Underworld". Dante Studies. 107: 1–31. JSTOR 40166378.

- ^ Heller-Roazen, Daniel (1998). "The Matter of Language: Guilhem de Peitieus and the Platonic Tradition". Modern Language Notes. 113 (4): 851–80. doi:10.1353/mln.1998.0056. JSTOR 3251406.

- ^ Kleinhenz, Christopher (1974). "Dante's Towering Giants: Inferno xxxi". . 27: 269–85.

- ^ Kleinhenz, Christopher (1980). "Plutus, Fortune, and Michael: The Eternal Triangle". Dante Studies. 98: 35–52. JSTOR 40166286.

- ^ Donoghue, Denis (1977). "On the Limits of a Language". The Sewanee Review. 85 (3): 371–91. JSTOR 27543259.

- ^ Rabkin, Eric S. (1979). "Metalinguistics and Science Fiction". Critical Inquiry. 6 (1). JSTOR 1343087.

- ^ Szörényi, László (2009). "Nimród zsoltára - Ősmagyar Dante Poklában?". Irodalmi Jelen. 9 (3).

- Divine Comedy

- Nimrod

- Gibberish language