Rational animal

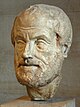

The term rational animal (Latin: animal rationale or animal rationabile) refers to a classical definition of humanity or human nature, associated with Aristotelianism.[1]

History[]

While the Latin term itself originates in scholasticism, it reflects the Aristotelian view of man as a creature distinguished by a rational principle. In the Nicomachean Ethics I.13, Aristotle states that the human being has a rational principle (Greek: λόγον ἔχον), on top of the nutritive life shared with plants, and the instinctual life shared with other animals, i. e., the ability to carry out rationally formulated projects.[2] That capacity for deliberative imagination was equally singled out as man's defining feature in De anima III.11.[3] While seen by Aristotle as a universal human feature, the definition applied to wise and foolish alike, and did not in any way imply necessarily the making of rational choices, as opposed to the ability to make them.[4]

The Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry defined man as a "mortal rational animal", and also considered animals to have a (lesser) rationality of their own.[5]

The definition of man as a rational animal was common in scholastical philosophy.[6] Catholic Encyclopedia states that this definition means that "in the system of classification and definition shown in the Arbor Porphyriana, man is a substance, corporeal, living, sentient, and rational".[6]

In Meditation II of Meditations on First Philosophy, Descartes arrives at his famous cogito ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am") claim. He then goes on to wonder "What am I?" He considers and rejects the scholastic concept of the "rational animal":

Shall I say 'a rational animal'? No; for then I should have to inquire what an animal is, what rationality is, and in this one question would lead me down the slope to other harder ones.[7]

Modern use[]

Freud was as aware as any of the irrational forces at work in humankind, but he nevertheless resisted what he called too much “stress on the weakness of the ego in relation to the id and of our rational elements in the face of the daemonic forces within us”.[8]

Neo-Kantian philosopher Ernst Cassirer, in his work An Essay on Man (1944), altered Aristotle's definition to label man as a symbolic animal. This definition has been influential in the field of philosophical anthropology, where it has been reprised by Gilbert Durand, and has been echoed in the naturalist description of man as the compulsive communicator.[9]

Sociologists in the tradition of Max Weber distinguish rational behavior (means-end oriented) from irrational, emotional or confused behavior, as well as from traditional-oriented behavior, but recognise the wide role of all the latter types in human life.[10]

Ethnomethodology sees rational human behavior as representing perhaps 1/10 of the human condition, dependent on the 9/10ths of background assumptions which provide the frame for means-end decision making.[11]

In his An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish, Bertrand Russell argues against the idea that man is rational, saying "Man is a rational animal — so at least I have been told. Throughout a long life I have looked diligently for evidence in favour of this statement, but so far I have not had the good fortune to come across it."[12]

See also[]

- Communicative rationality

- Donald Davidson

- Economic man

- Erasmus

- Genus-differentia definition

- Neocortex

- Reality principle

- Thomas Paine

- John von Neumann

- Behavioural science

References[]

- ^ "Animal Cognition". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. 2021.

- ^ Aristotle, Ethics (1976) p. 75 and p. 88

- ^ B. P. Stigum, Econometrics and the Philosophy of Economics (2003) p. 194

- ^ Stigum, p. 198

- ^ L. Johnson, Power Knowledge Animals (2012) p. 80

- ^ a b

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Man". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Man". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ The Philosophical Writings of Descartes Volume II. Translated by John Cottingham, Robert Stoothoff, Dugald Murdoch. Cambridge University Press. 1984.

- ^ S. Freud, On Psychopathology (PFL 10) p. 247

- ^ D. Attenborough, Life on Earth (1992) Ch 13

- ^ Alfred Schutz, The Phenomenology of the Social World (1997) p. 240

- ^ A. Giddens, Positivism and Sociology (1974) p. 72

- ^ Russell, Bertrand (1943). An Outline of Intellectual Rubbish. Girard, Kansas: Haldeman-Julius Publications. OCLC 3656132.

External links[]

- Philosophy of Aristotle

- Cognition

- Scholasticism