Telos

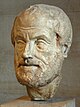

Telos (/ˈtɛ.lɒs/; Greek: τέλος, translit. télos, lit. "end, 'purpose', or 'goal'")[1] is a term used by philosopher Aristotle to refer to the full potential or inherent purpose or objective of a person or thing,[2] similar to the notion of an 'end goal' or 'raison d'être'. Moreover, it can be understood as the "supreme end of man's endeavour".[3]

"Pleasure and pain moreover supply the motives of desire and of avoidance, and the springs of conduct generally. This being so, it clearly follows that actions are right and praiseworthy only as being a means to the attainment of a life of pleasure. But that which is not itself a means to anything else, but to which all else is a means, is what the Greeks term the Telos, the highest, ultimate or final Good. It must therefore be admitted that the Chief Good is to live agreeably."

— Cicero, De Finibus Bonorum et Malorum, Book I[4]

Telos is the root of the modern term teleology, the study of purposiveness or of objects with a view to their aims, purposes, or intentions. Teleology is central in Aristotle's work on plant and animal biology, and human ethics, through his theory of the four causes. Aristotle's notion that everything has a telos also gave rise to epistemology.[5] It is also central to some philosophical theories of history, such as those involving messianic redemption, such as Christian salvation history those of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx.[2]

In general philosophy[]

Telos has been consistently used in the writings of Aristotle, in which the term, on several occasions, denotes 'goal'.[6] It is considered synonymous to teleute ('end'), particularly in Aristotle's discourse about the plot-structure in Poetics.[6] The philosopher went as far as to say that telos can encompass all forms of human activity.[7] One can say, for instance, that the telos of warfare is victory, or the telos of business is the creation of wealth. Within this conceptualization, there are telos that are subordinate to other telos, as all activities have their own, respective goals.

For Aristotle, these subordinate telos can become the means to achieve more fundamental telos.[7] Through this concept, for instance, the philosopher underscored the importance of politics and that all other fields are subservient to it. He explained that the telos of the blacksmith is the production of a sword, while that of the swordsman's, which uses the weapon as a tool, is to kill or incapacitate an enemy.[8] On the other hand, the telos of these occupations are merely part of the purpose of a ruler, who must oversee the direction and well-being of a state.[8]

Telos vs techne[]

Telos is associated with the concept called techne, which is the rational method involved in producing an object or accomplishing a goal or objective. In the Theuth/Thamus myth, for instance, the section covering techne referred to telos and techne together.[9] The two methods are, however, not mutually exclusive in principle. These are demonstrated in the cases of writing and seeing, as explained by Martin Heidegger: the former is considered a form of techne, as the end product lies beyond (para) the activity of producing; whereas, in seeing, there is no remainder outside of or beyond the activity itself at the moment it is accomplished.[10] Aristotle, for his part, simply designated sophia (also referred to as the arete or excellence of philosophical reflection) as the consummation or the final cause (telos) of techne.[11] Heidegger attempted to explain the Aristotelian conceptualization outlined in the Nicomachean Ethics, where the eidos - the soul of the maker - was treated as the arche of the thing made (ergon).[12] In this analogy, the telos constitutes the arche but in a certain degree not at the disposition of techne.[12]

In philosophy of science[]

One running debate in modern philosophy of biology is to what extent does teleological language (i.e., the 'purposes' of various organs or life-processes) remain unavoidable, and when does it simply become a shorthand for ideas that can ultimately be spelled out non-teleologically.

According to Aristotle, the telos of a plant or animal is also "what it was made for"—which can be observed.[2] Trees, for example, seem to be made to grow, produce fruit/nuts/flowers, provide shade, and reproduce. Thus, these are all elements of trees' telos. Moreover, trees only possess such elements if it is healthy and thriving—"only if it lives long enough and under the right conditions to fulfill its potential."[2]

In social philosophy[]

Action theory also makes essential use of teleological vocabulary. From Donald Davidson's perspective, an action is just something an agent does with an intention—i.e., looking forward to some end to be achieved by the action.[13] Action is considered just a step that is necessary to fulfill human telos, as it leads to habits.[13]

According to the Marxist perspective, historical change is dictated by socio-economic structures, which means that laws largely determine the realization of the telos of the class struggle.[14] Thus, as per the work of Hegel and Marx, historical trends, too, have telos.[2]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Teleological ethics." Encyclopædia Britannica 2008 [1998].

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Telos." Philosophy Terms. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Introduction to 'de Finabus'." Cicero: de Finibus XVII (2nd ed.). Loeb Classical Library. Harvard University Press (1931), transcribed by B. Thayer.

- ^ Rackham, H. Harris, trans. 1931. "Book I." In Cicero: de Finibus XVII (2nd ed.). Loeb Classical Library, Harvard University Press, transcribed by B. Thayer. p. 42.

- ^ Eagles, Munroe (2008). Politics: An Introduction to Modern Democratic Government. Ontario: Broadview Press. p. 87. ISBN 9781551118581.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Nyusztay, Ivan (2002). Myth, Telos, Identity: The Tragic Schema in Greek and Shakespearean Drama. New York: Rodopi. p. 84. ISBN 9042015403.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Baggini, Julian (2016). Philosophy: Key Texts. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 14. ISBN 9780333964859.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Grayling, A. C. (2019-06-20). The History of Philosophy. Penguin UK. ISBN 9780241980866.

- ^ Griswold, Charles (2010). Self-Knowledge in Plato's Phaedrus. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press. p. 160. ISBN 0-271-01618-3.

- ^ McNeill, William (2012). Time of Life, The: Heidegger and Ethos. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0791467831.

- ^ Rojcewicz, Richard (2006). The Gods and Technology: A Reading of Heidegger. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 64. ISBN 9780791466414.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Radloff, Bernhard (2007). Heidegger and the Question of National Socialism: Disclosure and Gestalt. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-8020-9315-8.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Altshuler, Roman; Sigrist, Michael J. (2016-06-10). Time and the Philosophy of Action. Routledge. ISBN 9781317819479.

- ^ Fløistad, Guttorm (2012). Volume 3: Philosophy of Action. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 10. ISBN 9789024732999.

External links[]

- Teleological Notions in Biology, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Alexander, Victoria N. Narrative Telos: The Ordering Tendencies of Chance. Dactyl Foundation.

- Philosophy of Aristotle

- Concepts in ancient Greek metaphysics