Wealth

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2011) |

Wealth is the abundance of valuable financial assets or physical possessions which can be converted into a form that can be used for transactions. This includes the core meaning as held in the originating old English word weal, which is from an Indo-European word stem.[2] The modern concept of wealth is of significance in all areas of economics, and clearly so for growth economics and development economics, yet the meaning of wealth is context-dependent. An individual possessing a substantial net worth is known as wealthy. Net worth is defined as the current value of one's assets less liabilities (excluding the principal in trust accounts).[3]

At the most general level, economists may define wealth as "anything of value" that captures both the subjective nature of the idea and the idea that it is not a fixed or static concept. Various definitions and concepts of wealth have been asserted by various individuals and in different contexts.[4] Defining wealth can be a normative process with various ethical implications, since often wealth maximization is seen as a goal or is thought to be a normative principle of its own.[5][6] A community, region or country that possesses an abundance of such possessions or resources to the benefit of the common good is known as wealthy.

The United Nations definition of inclusive wealth is a monetary measure which includes the sum of natural, human, and physical assets.[7][8] Natural capital includes land, forests, energy resources, and minerals. Human capital is the population's education and skills. Physical (or "manufactured") capital includes such things as machinery, buildings, and infrastructure.

History[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (January 2019) |

Adam Smith, in his seminal work The Wealth of Nations, described wealth as "the annual produce of the land and labour of the society". This "produce" is, at its simplest, that which satisfies human needs and wants of utility.

In popular usage, wealth can be described as an abundance of items of economic value, or the state of controlling or possessing such items, usually in the form of money, real estate and personal property. An individual who is considered wealthy, affluent, or rich is someone who has accumulated substantial wealth relative to others in their society or reference group.

In economics, net worth refers to the value of assets owned minus the value of liabilities owed at a point in time.[9] Wealth can be categorized into three principal categories: personal property, including homes or automobiles; monetary savings, such as the accumulation of past income; and the capital wealth of income producing assets, including real estate, stocks, bonds, and businesses.[citation needed] All these delineations make wealth an especially important part of social stratification. Wealth provides a type of individual safety net of protection against an unforeseen decline in one's living standard in the event of job loss or other emergency and can be transformed into home ownership, business ownership, or even a college education.[citation needed]

Wealth has been defined as a collection of things limited in supply, transferable, and useful in satisfying human desires.[10] Scarcity is a fundamental factor for wealth. When a desirable or valuable commodity (transferable good or skill) is abundantly available to everyone, the owner of the commodity will possess no potential for wealth. When a valuable or desirable commodity is in scarce supply, the owner of the commodity will possess great potential for wealth.

'Wealth' refers to some accumulation of resources (net asset value), whether abundant or not. 'Richness' refers to an abundance of such resources (income or flow). A wealthy individual, community, or nation thus has more accumulated resources (capital) than a poor one. The opposite of wealth is destitution. The opposite of richness is poverty.

The term implies a social contract on establishing and maintaining ownership in relation to such items which can be invoked with little or no effort and expense on the part of the owner. The concept of wealth is relative and not only varies between societies, but varies between different sections or regions in the same society. A personal net worth of US$10,000 in most parts of the United States would certainly not place a person among the wealthiest citizens of that locale. However, such an amount would constitute an extraordinary amount of wealth in impoverished developing countries.

Concepts of wealth also vary across time. Modern labor-saving inventions and the development of the sciences have vastly improved the standard of living in modern societies for even the poorest of people. This comparative wealth across time is also applicable to the future; given this trend of human advancement, it is possible that the standard of living that the wealthiest enjoy today will be considered impoverished by future generations.

Industrialization emphasized the role of technology. Many jobs were automated. Machines replaced some workers while other workers became more specialized. Labour specialization became critical to economic success. However, physical capital, as it came to be known, consisting of both the natural capital and the infrastructural capital, became the focus of the analysis of wealth.[citation needed]

Adam Smith saw wealth creation as the combination of materials, labour, land, and technology in such a way as to capture a profit (excess above the cost of production).[11] The theories of David Ricardo, John Locke, John Stuart Mill, in the 18th century and 19th century built on these views of wealth that we now call classical economics.

Marxian economics (see labor theory of value) distinguishes in the Grundrisse between material wealth and human wealth, defining human wealth as "wealth in human relations"; land and labour were the source of all material wealth. The German cultural historian Silvio Vietta links wealth/poverty to rationality. Having a leading position in the development of rational sciences, in new technologies and in economic production leads to wealth, while the opposite can be correlated with poverty.[12][13]

Wealth creation[]

Billionaires[14] such as Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos, Warren Buffett, Elon Musk, Charlie Munger and others advise the following principles of wealth creation:

- Science and scientific method[15][16]

- Economics and continuous lifelong learning[17]

- Reading and education[18][19]

- Learning from rich people – billionaires and millionaires.[20][21]

Amount of wealth in the world[]

The wealth of households amounts to US$280 trillion (2017). According to the eighth edition of the Global Wealth Report, in the year to mid-2017, total global wealth rose at a rate of 6.4%, the fastest pace since 2012 and reached US$280 trillion, a gain of US$16.7 trillion. This reflected widespread gains in equity markets matched by similar rises in non-financial assets, which moved above the pre-crisis year 2007's level for the first time this year. Wealth growth also outpaced population growth, so that global mean wealth per adult grew by 4.9% and reached a new record high of US$56,540 per adult. Tim Harford has asserted that a small child has greater wealth than the 2 billion poorest people in the world combined, since a small child has no debt.[22]

Wealthiest cities[]

World's 15 richest cities in 2017.[23]

| City | Wealth |

|---|---|

| New York City | $3 Trillion |

| London | $2.7 Trillion |

| Tokyo | $2.5 Trillion |

| San Francisco Bay Area | $2.3 Trillion |

| Beijing | $2.2 Trillion |

| Shanghai | $2 Trillion |

| Los Angeles | $1.4 Trillion |

| Hong Kong | $1.3 Trillion |

| Sydney | $1 Trillion |

| Singapore | $1 Trillion |

| Chicago | $0.98 Trillion |

| Mumbai | $0.94 Trillion |

| Toronto | $0.94 Trillion |

| Frankfurt | $0.91 Trillion |

| Paris | $0.8 Trillion |

Philosophical analysis[]

In Western civilization, wealth is connected with a quantitative type of thought, invented in the ancient Greek "revolution of rationality", involving for instance the quantitative analysis of nature, the rationalization of warfare, and measurement in economics.[12][13] The invention of coined money and banking was particularly important. Aristotle describes the basic function of money as a universal instrument of quantitative measurement – "for it measures all things […]" – making things alike and comparable due to a social "agreement" of acceptance.[24] In that way, money also enables a new type of economic society and the definition of wealth in measurable quantities, such as gold and money. Modern philosophers like Nietzsche criticized the fixation on measurable wealth: "Unsere ‘Reichen' – das sind die Ärmsten! Der eigentliche Zweck alles Reichtums ist vergessen!" ("Our 'rich people' – those are the poorest! The real purpose of all wealth has been forgotten!")[25]

Economic analysis[]

In economics, wealth (in a commonly applied accounting sense, sometimes savings) is the net worth of a person, household, or nation – that is, the value of all assets owned net of all liabilities owed at a point in time. For national wealth as measured in the national accounts, the net liabilities are those owed to the rest of the world.[26] The term may also be used more broadly as referring to the productive capacity of a society or as a contrast to poverty.[27] Analytical emphasis may be on its determinants or distribution.[28]

Economic terminology distinguishes between wealth and income. Wealth or savings is a stock variable – that is, it is measurable at a date in time, for example the value of an orchard on December 31 minus debt owed on the orchard. For a given amount of wealth, say at the beginning of the year, income from that wealth, as measurable over say a year is a flow variable. What marks the income as a flow is its measurement per unit of time, such as the value of apples yielded from the orchard per year.

In macroeconomic theory the 'wealth effect' may refer to the increase in aggregate consumption from an increase in national wealth. One feature of its effect on economic behavior is the wealth elasticity of demand, which is the percentage change in the amount of consumption goods demanded for each one-percent change in wealth.

Wealth may be measured in nominal or real values – that is, in money value as of a given date or adjusted to net out price changes. The assets include those that are tangible (land and capital) and financial (money, bonds, etc.). Measurable wealth typically excludes intangible or nonmarketable assets such as human capital and social capital. In economics, 'wealth' corresponds to the accounting term 'net worth', but is measured differently. Accounting measures net worth in terms of the historical cost of assets while economics measures wealth in terms of current values. But analysis may adapt typical accounting conventions for economic purposes in social accounting (such as in national accounts). An example of the latter is generational accounting of social security systems to include the present value projected future outlays considered to be liabilities.[29] Macroeconomic questions include whether the issuance of government bonds affects investment and consumption through the wealth effect.[30]

Environmental assets are not usually counted in measuring wealth, in part due to the difficulty of valuation for a non-market good. Environmental or green accounting is a method of social accounting for formulating and deriving such measures on the argument that an educated valuation is superior to a value of zero (as the implied valuation of environmental assets).[31]

Sociological treatments[]

Wealth and social class[]

Social class is not identical to wealth, but the two concepts are related (particularly in Marxist theory),[32] leading to the concept of socioeconomic status. Wealth at the individual or household level refers to value of everything a person or family owns, including personal property and financial assets.[33]

In both Marxist and Weberian theory, class is divided into upper, middle, and lower, with each further subdivided (e.g., upper middle class).[32]

The upper class are schooled to maintain their wealth and pass it to future generations.[34]

The middle class views wealth as something for emergencies and it is seen as more of a cushion. This class comprises people that were raised with families that typically owned their own home, planned ahead and stressed the importance of education and achievement. They earn a significant amount of income and also have significant amounts of consumption. However, there is limited savings (deferred consumption) or investments, besides retirement pensions and home ownership.[34]

Below the middle class, the working class and poor have the least amount of wealth, with circumstances discouraging accumulation of assets.[34]

Distribution[]

Although precise data are not available, the total household wealth in the world, excluding human capital, has been estimated at $125 trillion (US$125×1012) in year 2000.[36] Including human capital, the United Nations estimated it in 2008 to be $118 trillion in the United States alone.[7][8] According to the Kuznet's Hypothesis, inequality of wealth and income increases during the early phases of economic development, stabilizes and then becomes more equitable.

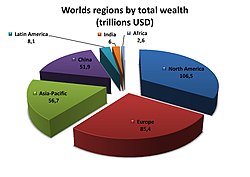

As of 2008, about 90% of global wealth is distributed in North America, Europe, and "rich Asia-Pacific" countries,[37] and in 2008, 1% of adults were estimated to hold 40% of world wealth, a number which falls to 32% when adjusted for purchasing power parity.[38] According to Richard H Ropers, the concentration of wealth in the United States is inequitably distributed.[39]

In 2013, 1% of adults were estimated to hold 46% of world wealth[40] and around $18.5 trillion was estimated to be stored in tax havens worldwide.[41]

See also[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Wealth |

- Gross National Happiness

- Happiness economics

- Productivity improving technologies (historical)

- Quality of life

- Working time

- List of wealthiest historical figures

References[]

- ^ "Total wealth per capita". Our World in Data. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- ^ "weal". The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Houghton Mifflin Company. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ^ "The Millionaire Next Door". movies2.nytimes.com. Retrieved September 27, 2018.

- ^ Denis "Authentic Development: Is it Sustainable?", pp. 189–205 in Building Sustainable Societies, Dennis Pirages, ed., M.E. Sharpe, ISBN 1-56324-738-0, 978-1-56324-738-5. (1996)

- ^ Kronman, Anthony T. (March 1980). "Wealth Maximization as a Normative Principle". The Journal of Legal Studies. 9 (2): 227–42. doi:10.1086/467637. S2CID 153759163.

- ^ Robert L. Heilbroner, 1987 2008. The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 880–83. Brief preview link.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Free exchange: The real wealth of nations". The Economist. June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Inclusive Wealth Report". Ihdp.unu.edu. IHDP. July 9, 2012. Archived from the original on June 30, 2012. Retrieved July 14, 2012.

- ^ "Net worth of wwe superstars". Retrieved August 27, 2017.

- ^ "How Wealth is Created". World Book Encyclopedia. 15. The Grolier Society. 1949. p. 5357.

- ^ Smith, Adam. An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vietta, Silvio (2013). A Theory of Global Civilization: Rationality and the Irrational as the Driving Forces of History. Kindle Ebooks.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vietta, Silvio (2012). Rationalität. Eine Weltgeschichte. Europäische Kulturgeschichte und Globalisierung. Fink.

- ^ "The World's Billionaires". Forbes. Retrieved April 8, 2017.

- ^

- caltech (October 25, 2016), Bill Gates Conversation with Caltech Students

- Gates, Bill. "Science is the Great Giver". gatesnotes.com.

- TCCTrueCompass (April 1, 2013), Ted Talks – Elon Musk on Innovation

- ^

- Y Combinator (August 16, 2016), Mark Zuckerberg : How to Build the Future

- Investors Archive (February 7, 2017), Billionaire Charles Koch: Building and Running an Empire

- ^

- Fortune Magazine (October 31, 2013), Best Advice: Warren Buffett and Charlie Munger | Fortune, retrieved April 8, 2017

- Evan Carmichael (August 14, 2015), Charlie Munger's Top 10 Rules For Success

- Buffett, Warren E.; Munger, Charles T. (2005). Kaufman, Peter D. (ed.). Poor Charlie's Almanack: The Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger (Expanded Third ed.). Virginia Beach, Va.: Walsworth Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1578645015.

- Bloomberg TV Markets and Finance (August 23, 2017), The David Rubenstein Show: Ginni Rometty

- "Zhou Qunfei: from lowly factory worker to China's richest woman". South China Morning Post.

- ^

- Shiao-Yen Wu (February 4, 2014), The Extraordinaire: Queen of Seattle Real Estate, Creative iTV

- CNBC International (June 24, 2017), Zhang Xin, CEO of SOHO China | The Brave Ones

- "Find Out What Bill Gates Says is His No. 1 Piece of Personal Finance Advice". GOBankingRates. February 11, 2014.

- UWTV (July 8, 2014), The Opportunity Ahead: A Conversation with Bill Gates

- "Lessons in Philanthropy 2017". www.facebook.com.

- Investors Archive (June 3, 2017), Billionaire Kenneth Griffin: Investment Strategy, Hedge Funds and Government (2017)

- ^

- Evan Carmichael (May 23, 2015), Warren Buffett's Top 10 Rules For Success (@WarrenBuffett)

- thegatesnotes (December 5, 2016), Holiday Books 2016

- "Learn more about Books | Bill Gates".

- Evan Carmichael (June 25, 2016), Elon Musk's Top Book Recommendations – #FavoriteBooks

- "18 Book Recommendations From Billionaire Warren Buffett". Inc.com. November 3, 2016.

- Uni Common Knowledge 3 (November 26, 2016), Jeff Bezos – Start Small, and You MIGHT Succeed Big

- Baer, Drake (September 3, 2014). "9 Books Billionaire Warren Buffett Thinks Everyone Should Read". Business Insider Australia.

- ^ The New York Times (November 30, 2017), Jay-Z and Dean Baquet, in Conversation

- ^ "The World's Billionaires". Forbes.

- ^ "Global Wealth Report." (October 18, 2018). Credit Suisse Research Institute. Credit-Suisse.com. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ Dr. Amarendra Bhushan Dhiraj (February 12, 2018). "World's 15 Richest Cities In 2017: New York, London, And Tokyo, Tops List". CEO World Magazine.

- ^ Aristotle. Nicomachean Ethics. p. 1133a.

- ^ Nietzsche. Werke in drei Bänden. III. p. 419.

- ^ • Paul A. Samuelson and William D. Nordhaus, 2004, 18th ed. Economics, "Glossary of Terms."

• Nancy D. Ruggles, 1987. "social accounting," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 377–82, esp. p. 380. - ^ • Adam Smith, 1776. The Wealth of Nations.

• David S. Landes, 1998. The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. Review.

• Partha Dasgupta, 1993. An Inquiry into Well-Being and Destitution. Description and review. - ^ • John Bates Clark, 1902. The Distribution of Wealth Analytical Table of Contents.

• E.N. Wolff, 2002. "Wealth Distribution," International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences, pp. 16394-16401. Abstract.

• Robert L. Heilbroner, 1987. [2008]). The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 4, pp. 880–83. Brief preview link. - ^ • Jagadeesh Gokhale, 2008. "Generational accounting." The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract and uncorrected proof.

• Laurence J. Kotlikoff, 1992, Generational Accounting. Free Press. - ^ Robert J. Barro, 1974. "Are Government Bonds Net Wealth?", Journal of Political Economy, 8(6), pp. 1095–111.

- ^ • Sjak Smulders, 2008. "green national accounting," The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, 2nd Edition. Abstract.

• United States National Research Council, 1994. Assigning Economic Value to Natural Resources, National Academy Press. Chapter-preview links. - ^ Jump up to: a b Grant, J. Andrew (2001). "class, definition of". In Jones, R.J. Barry (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of International Political Economy: Entries A–F. Taylor & Francis. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-415-24350-6.

- ^ Team, The Investopedia. "Wealth Definition". Investopedia. Retrieved June 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sherraden, Michael. Assets and the Poor: A New American Welfare Policy. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe, Inc., 1991.

- ^ "Trends in Family Wealth, 1989 to 2013". Congressional Budget Office. August 18, 2016.

- ^ "The World Distribution of Household Wealth". Wider.unu.edu.

- ^ James B. Davies, Susanna Sandström, Anthony Shorrocks, and Edward N. Wolff. (2008). The World Distribution of Household Wealth, p8. UNU-WIDER.

- ^ James B. Davies, Susanna Sandström, Anthony Shorrocks, and Edward N. Wolff. (2008). The World Distribution of Household Wealth. UNU-WIDER.

- ^ Ropers, Richard H, Ph.D. Persistent Poverty: The American Dream Turned Nightmare. New York: Insight Books, 1991.

- ^ "Global Wealth Report 2013". Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- ^ "Tax on the 'private' billions now stashed away in havens enough to end extreme world poverty twice over". Oxfam International. May 22, 2013. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2014.

- Wealth