Religion in China

Religion in China (CFPS 2014)[1][2][note 1]

| Religion by country |

|---|

|

|

China officially espouses state atheism,[3] but in reality many Chinese citizens, including Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members, practice some kind of Chinese folk religion. Chinese civilization has historically long been a cradle and host to a variety of the most enduring religio-philosophical traditions of the world. Confucianism and Taoism (Daoism), later joined by Buddhism, constitute the "three teachings" that have shaped Chinese culture. There are no clear boundaries between these intertwined religious systems, which do not claim to be exclusive, and elements of each enrich popular or folk religion. The emperors of China claimed the Mandate of Heaven and participated in Chinese religious practices. In the early 20th century, reform-minded officials and intellectuals attacked all religions as "superstitious", and since 1949, China has been governed by the CCP, an atheist institution that prohibits party members from practicing religion while in office. In the culmination of a series of atheistic and anti-religious campaigns already underway since the late 19th century, the Cultural Revolution against old habits, ideas, customs and culture, lasting from 1966 to 1976, destroyed or forced them underground.[4][5]: 138 Under subsequent leaders, religious organisations were given more autonomy. The government formally recognizes five religions: Buddhism, Taoism, Catholicism, Protestantism, and Islam. In the early twenty-first century there has been increasing official recognition of Confucianism and Chinese folk religion as part of China's cultural inheritance.

Folk or popular religion, the most widespread system of beliefs and practices, has evolved and adapted since at least the Shang and Zhou dynasties in the second millennium BCE. Fundamental elements of a theology and spiritual explanation for the nature of the universe harken back to this period and were further elaborated in the Axial Age. Basically, Chinese religion involves allegiance to the shen, often translated as "spirits", defining a variety of gods and immortals. These may be deities of the natural environment or ancestral principles of human groups, concepts of civility, culture heroes, many of whom feature in Chinese mythology and history.[6] Confucian philosophy and religious practice began their long evolution during the later Zhou; Taoist institutionalized religions developed by the Han dynasty; Chinese Buddhism became widely popular by the Tang dynasty, and in response Confucian thinkers developed Neo-Confucian philosophies; and popular movements of salvation and local cults thrived.

Christianity and Islam arrived in China in the 7th century. Christianity did not take root until it was reintroduced in the 16th century by Jesuit missionaries.[7] In the early 20th century Christian communities grew, but after 1949, foreign missionaries were expelled, and churches brought under government-controlled institutions. After the late 1970s, religious freedoms for Christians improved and new Chinese groups emerged.[8]: 508, 532 Islam has been practiced in Chinese society for 1,400 years.[9] Currently, Muslims are a minority group in China, representing between 0.45% to 1.8% of the total population according to the latest estimates.[1][10] Though Hui Muslims are the most numerous group,[11] the greatest concentration of Muslims is in Xinjiang, with a significant Uyghur population. China is also often considered a home to humanism and secularism, this-worldly ideologies beginning in the time of Confucius.

Because many Han Chinese do not consider their spiritual beliefs and practices to be a "religion" and do not feel that they must practice any one of them exclusively, it is difficult to gather clear and reliable statistics. According to scholarly opinion, "the great majority of China's population of 1.4 billion" takes part in Chinese cosmological religion, its rituals and festivals of the lunar calendar, without belonging to any institutional teaching.[12] National surveys conducted in the early 21st century estimated that some 80% of the population of China, which is more than a billion people, practice some kind of Chinese folk religion; 13–16% are Buddhists; 10% are Taoist; 2.53% are Christians; and 0.83% are Muslims. Folk religious movements of salvation constitute 2–3% to 13% of the population, while many in the intellectual class adhere to Confucianism as a religious identity. In addition, ethnic minority groups practice distinctive religions, including Tibetan Buddhism, and Islam among the Hui and Uyghur peoples.

History[]

Proto-Chinese and Xia-Shang-Zhou culture[]

Prior to the formation of Chinese civilisation and the spread of world religions in the region known today as East Asia (which includes the territorial boundaries of modern-day China), local tribes shared animistic, shamanic and totemic worldviews. Mediatory individuals such as shamans communicated prayers, sacrifices or offerings directly to the spiritual world, a heritage that survives in some modern forms of Chinese religion.[16]

Ancient shamanism is especially connected to ancient Neolithic cultures such as the Hongshan culture.[17] The Flemish philosopher Ulrich Libbrecht traces the origins of some features of Taoism to what Jan Jakob Maria de Groot called "Wuism",[18] that is Chinese shamanism.[19]

Libbrecht distinguishes two layers in the development of the Chinese theology and religion that continues to this day, traditions derived respectively from the Shang (1600–1046 BCE) and subsequent Zhou dynasties (1046–256 BCE). The religion of the Shang was based on the worship of ancestors and god-kings, who survived as unseen divine forces after death. They were not transcendent entities, since the universe was "by itself so", not created by a force outside of it but generated by internal rhythms and cosmic powers. The royal ancestors were called di (帝), "deities", and the utmost progenitor was Shangdi (上帝 "Highest Deity"). Shangdi is identified with the dragon, symbol of the unlimited power (qi),[19] of the "protean" primordial power which embodies yin and yang in unity, associated to the constellation Draco which winds around the north ecliptic pole,[13] and slithers between the Little and Big Dipper (or Great Chariot). Already in Shang theology, the multiplicity of gods of nature and ancestors were viewed as parts of Di, and the four 方 fāng ("directions" or "sides") and their 風 fēng ("winds") as his cosmic will.[20]

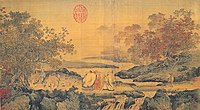

The Zhou dynasty, which overthrew the Shang, was more rooted in an agricultural worldview, and they emphasised a more universal idea of Tian (天 "Heaven").[19] The Shang dynasty's identification of Shangdi as their ancestor-god had asserted their claim to power by divine right; the Zhou transformed this claim into a legitimacy based on moral power, the Mandate of Heaven. In Zhou theology, Tian had no singular earthly progeny, but bestowed divine favour on virtuous rulers. Zhou kings declared that their victory over the Shang was because they were virtuous and loved their people, while the Shang were tyrants and thus were deprived of power by Tian.[21]

John C. Didier and David Pankenier relate the shapes of both the ancient Chinese characters for Di and Tian to the patterns of stars in the northern skies, either drawn, in Didier's theory by connecting the constellations bracketing the north celestial pole as a square,[22] or in Pankenier's theory by connecting some of the stars which form the constellations of the Big Dipper and broader Ursa Major, and Ursa Minor (Little Dipper).[23] Cultures in other parts of the world have also conceived these stars or constellations as symbols of the origin of things, the supreme godhead, divinity and royal power.[24]