Axial Age

| Part of a series on | |||

| Human history Human Era | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| ↑ Prehistory (Pleistocene epoch) | |||

| Holocene | |||

|

|||

| Ancient | |||

|

|||

| Postclassical | |||

|

|||

| Modern | |||

|

|||

| ↓ Future | |||

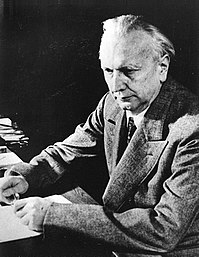

Axial Age (also Axis Age,[1] from German: Achsenzeit) is a term coined by German philosopher Karl Jaspers in the sense of a "pivotal age", characterizing the period of ancient history from about the 8th to the 3rd century BCE.

During this period, according to Jaspers' concept, new ways of thinking appeared in Persia, India, China, Palestine, and the Greco-Roman world in religion and philosophy, in a striking parallel development, without any obvious direct cultural contact between all of the participating Eurasian cultures. Jaspers identified key thinkers from this age who had a profound influence on future philosophies and religions, and identified characteristics common to each area from which those thinkers emerged.

Although the concept of the existence of an 'axial age' has been influential, its historical legitimacy is problematic.[2][3] Some criticisms of Jasper's rather generic formulation include the lack of a demonstrable common denominator between the intellectual developments that are supposed to have developed in unison across ancient Greece, Palestine, India, and China; lack of any radical discontinuity with 'preaxial' and 'postaxial' periods; and exclusion of pivotal figures that do not fit the definition (for example, Jesus, Muhammad, and Akhenaten).[4]

Definition[]

Jaspers introduced the concept of an Axial Age in his book Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte (The Origin and Goal of History),[5] published in 1949. The simultaneous appearance of thinkers and philosophers in different areas of the world had been remarked by numerous authors since the 18th century, notably by the French Indologist Abraham Hyacinthe Anquetil-Duperron.[6] Jaspers explicitly cited some of these authors, including Victor von Strauß (1859) and Peter Ernst von Lasaulx (1870).[6] He was unaware of the first fully nuanced theory from 1873 by John Stuart Stuart-Glennie, forgotten by Jaspers' time, and which Stuart-Glennie termed “the moral revolution”.[7] Stuart-Glennie and Jaspers both claimed that the Axial Age should be viewed as an objective empirical fact of history, independently of religious considerations.[8][9] Jaspers argued that during the Axial Age, "the spiritual foundations of humanity were laid simultaneously and independently in China, India, Persia, Judea, and Greece. And these are the foundations upon which humanity still subsists today".[10]

He identified a number of key thinkers as having had a profound influence on future philosophies and religions, and identified characteristics common to each area from which those thinkers emerged. Jaspers held up this age as unique and one to which the rest of the history of human thought might be compared.

Characteristics[]

Jaspers presented his first outline of the Axial age by a series of examples:

Confucius and Lao-Tse were living in China, all the schools of Chinese philosophy came into being, including those of Mo Ti, Chuang Tse, Lieh Tzu and a host of others; India produced the Upanishads and Buddha and, like China, ran the whole gamut of philosophical possibilities down to materialism, scepticism and nihilism; in Iran, Zarathustra taught a challenging view of the world as a struggle between good and evil; in Palestine the prophets made their appearance from Elijah by way of Isaiah and Jeremiah to Deutero-Isaiah; Greece witnessed the appearance of Homer, of the philosophers—Parmenides, Heraclitus and Plato,—of the tragedians, of Thucydides and Archimedes. Everything implied by these names developed during these few centuries almost simultaneously in China, India and the West.

— Karl Jaspers, Origin and Goal of History, p. 2

Jaspers described the Axial Age as "an interregnum between two ages of great empire, a pause for liberty, a deep breath bringing the most lucid consciousness".[11] It has also been suggested that the Axial Age was a historically liminal period, when old certainties had lost their validity and new ones were still not ready.[12]

Jaspers had a particular interest in the similarities in circumstance and thought of its figures. Similarities included an engagement in the quest for human meaning[13] and the rise of a new elite class of religious leaders and thinkers in China, India and the Mediterranean.[14]

These spiritual foundations were laid by individual thinkers within a framework of a changing social environment. Jaspers argues that the characteristics appeared under similar political circumstances: China, India, the Middle East and the Occident each comprised multiple small states engaged in internal and external struggles. The three regions all gave birth to, and then institutionalized, a tradition of travelling scholars, who roamed from city to city to exchange ideas. After the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period, Taoism and Confucianism emerged in China. In other regions, the scholars were largely from extant religious traditions; in India, from Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism; in Persia, from Zoroastrianism; in The Levant, from Judaism; and in Greece, from Sophism and other classical philosophies.

Many of the cultures of the axial age were considered second-generation societies because they were built on the societies which preceded them.[15]

Thinkers and movements[]

In China, the Hundred Schools of Thought (c. 6th century BCE) were in contention and Confucianism and Taoism arose during this era, and in this area it remains a profound influence on social and religious life.

Zoroastrianism, another of Jaspers' examples, is one of the first monotheistic religions. Mary Boyce believes it greatly influenced modern Abrahamic religions with such conceptions as the devil and Heaven/Hell.[16] William W. Malandra and R. C. Zaehner, suggest that Zoroaster may indeed have been an early contemporary of Cyrus the Great living around 550 BCE.[17] Boyce and other leading scholars who once supported much earlier dates for Zarathustra/Zoroaster have recently changed their position on the time when he likely lived, so that there is an emerging consensus regarding him as a contemporary or near-contemporary of Cyrus the Great.[18]

Jainism propagated the religion of sramanas (previous Tirthankaras) and influenced Indian philosophy by propounding the principles of ahimsa (non-violence), karma, samsara and asceticism.[19] Mahavira (24th Tirthankara in the 5th century BCE),[20][21] known as its fordmaker and a contemporary with the Buddha, lived during this age.[22][23][24]

Buddhism, also of the sramana tradition of India, was another of the world's most influential philosophies, founded by Siddhartha Gautama, or the Buddha, who lived c. 5th century BCE; its spread was aided by Ashoka, who lived late in the period.

Jaspers' axial shifts included the rise of Platonism (c. 4th century BCE), which would later become a major influence on the Western world through both Christianity and secular thought throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance.

Reception[]

In addition to Jaspers, the philosopher Eric Voegelin referred to this age as The Great Leap of Being, constituting a new spiritual awakening and a shift of perception from societal to individual values.[25] Thinkers and teachers like the Buddha, Pythagoras, Heraclitus, Parmenides, and Anaxagoras contributed to such awakenings which Plato would later call anamnesis, or a remembering of things forgotten.

David Christian notes that the first "universal religions" appeared in the age of the first universal empires and of the first all-encompassing trading networks.[26]

Anthropologist David Graeber has pointed out that "the core period of Jasper's Axial age [...] corresponds almost exactly to the period in which coinage was invented. What's more, the three parts of the world where coins were first invented were also the very parts of the world where those sages lived; in fact, they became the epicenters of Axial Age religious and philosophical creativity."[27] Drawing on the work of classicist Richard Seaford and literary theorist Marc Shell on the relation between coinage and early Greek thought, Graeber argues that an understanding of the rise of markets is necessary to grasp the context in which the religious and philosophical insights of the Axial age arose. The ultimate effect of the introduction of coinage was, he argues, an "ideal division of spheres of human activity that endures to this day: on the one hand the market, on the other, religion".[28]

German sociologist Max Weber played an important role in Jaspers' thinking.[29][30][31] Shmuel Eisenstadt argues in the introduction to The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations that Weber's work in his The Religion of China: Confucianism and Taoism, The Religion of India: The Sociology of Hinduism and Buddhism and Ancient Judaism provided a background for the importance of the period, and notes parallels with Eric Voegelin's Order and History.[14] Wider acknowledgement of Jaspers' work came after it was presented at a conference and published in Daedalus in 1975, and Jaspers' suggestion that the period was uniquely transformative generated important discussion among other scholars, such as Johann Arnason.[31] In literature, Gore Vidal in his novel Creation covers much of this Axial Age through the fictional perspective of a Persian adventurer.

Shmuel Eisenstadt analyses economic circumstances relating to the coming of the Axial Age in Greece.[32]

Religious historian Karen Armstrong explored the period in her The Great Transformation,[33] and the theory has been the focus of academic conferences.[34]

Usage of the term has expanded beyond Jaspers' original formulation. Yves Lambert argues that the Enlightenment was a Second Axial Age, including thinkers such as Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein, wherein relationships between religion, secularism, and traditional thought are changing.[35]

The validity of the concept has been called into question.

In 2006 Diarmaid MacCulloch called the Jaspers thesis "a baggy monster, which tries to bundle up all sorts of diversities over four very different civilisations, only two of which had much contact with each other during the six centuries that (after adjustments) he eventually singled out, between 800 and 200 BCE".[36]

In 2013, another comprehensive critique appears in Iain Provan's book Convenient Myths: The Axial Age, Dark Green Religion, and the World That Never Was.[37]

In 2018, contrary to Suzuki and Provan, and similar to Whitaker, Stephen Sanderson published another book dealing somewhat with the axial age and its religious contributions, arguing that religions and religious change in general are essentially biosocial adaptations to changing environments.[38]

References[]

- ^ Meister, Chad (2009). Introducing Philosophy of Religion. Abingdon: Routledge. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-203-88002-9.

- ^ Spinney L (2019). "When did societies become modern? 'Big history' dashes popular idea of Axial Age". Nature. 576 (7786): 189–190. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-03785-w.

- ^ Smith A (2015). "Between facts and myth: Karl Jaspers and the actuality of the axial age". International Journal of Philosophy and Theology. 76 (4): 315–334. doi:10.1080/21692327.2015.1136794.

- ^ Iain Provan, Convenient Myths: The Axial Age, Dark Green Religion, And The World That Never Was, 2013, Baylor, pp. 1-40.

- ^ Karl Jaspers, Origin and Goal of History, Routledge Revivals, 2011, p. 2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Metzler, Dieter (2009). "Achsenzeit als Ereignis und Geschichte" [Axial age as happening and history] (PDF). Internet-Beiträge zur Ägyptologie und Sudanarchäologie (IBAES) (in German). 10: 169. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ^ Eugene Halton; Palgrave Connect (Online service) (2014). From the Axial Age to the Moral Revolution: John Stuart-Glennie, Karl Jaspers, and a New Understanding of the Idea. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-137-47350-9.

- ^ Stuart-Glennie J. S., 1873, In the Morningland: Or, the Law of the Origin and Transformation of Christianity – Vol. 1: The New Philosophy of History. London: Longmans, Green, and Company, pp. vii–viii.

- ^ Jaspers K., The Origin and Goal of History, p. 1.

- ^ Jaspers, Karl (2003). The Way to Wisdom : An Introduction to Philosophy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-300-09735-2..

- ^ Jaspers 1953, p. 51 quoted in Armstrong 2006, p. 367.

- ^ Thomassen, Bjorn (2010), "Anthropology, multiple modernities and the axial age debate", Anthropological Theory, 10 (4): 321–42, doi:10.1177/1463499610386659, S2CID 143930719

- ^ Neville, Robert Cummings (2002). Religion in Late Modernity. SUNY Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-7914-5424-X.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Eisenstadt, SN (1986). "Introduction". The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations. SUNY Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 0-88706-094-3.

- ^ Pollard, Elizabeth; Rosenberg, Clifford; Tignor, Robert (2011). Worlds Together Worlds Apart. New York: Norton. p. 162. ISBN 978-0-393-91847-2.

- ^ Boyce, Mary (1979). Zoroastrians: Their Religious Beliefs and Practices. London: Routledge. p. 77. ISBN 0-415-23903-6.

- ^ (1983). An Introduction to Ancient Iranian Religion. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 0-8166-1114-9.

- ^ (2012). Three Testaments: Torah, Gospel, and Quran. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 23–24. ISBN 978-1-4422-1492-7.

- ^ Zydenbos, Robert J (2006). Jainism Today and Its Future. München: Manya Verlag. pp. 11, 56–57, 59..

- ^ Cort, John E. (2001). Jains in the World: Religious Values and Ideology in India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513234-2.

- ^ Rapson, E. J. (1955). The Cambridge History of India. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Mahavira", Britannica Concise Encyclopedia, Encyclopædia Britannica, 2006.

- ^ Fisher, Mary Pat (1997). Living Religions: An Encyclopedia of the World's Faiths. London: IB Tauris. p. 115. ISBN 1-86064-148-2.

- ^ "Rude Travel: Down The Sages Vir Sanghavi".

- ^ Voegelin, Eric (2000) [1985]. Order and History (Volume V): In Search of Order. Collected Works. 18. Columbia: The University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-1261-0.

- ^ Christian, David (2004). Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History. California World History Library. 2. University of California Press. p. 319. ISBN 978-0-520-23500-7. Retrieved 2013-12-29.

Not until the first millennium BCE do the first universal religions appear. Though associated in practice with particular dynasties or empires, they proclaimed universal truths and worshiped all-powerful gods. It is no accident that universal religions appeared when both empires and exchange networks reached to the edge of the known universe. Nor is it an accident that one of the earliest religions of this type, Zoroastrianism, appeared in the largest empire of the mid-first millennium BCE, that of the Achaemenids, and at the hub of trade routes that were weaving Afro-Eurasia into a single world system. Indeed, most of the universal religions appeared in the hub region between Mesopotamia and northern India. They included Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism in Persia, Buddhism in India, Confucianism in China, and Judaism, Christianity and Islam in the Mediterranean world.

- ^ Graeber 2011, p. 224.

- ^ Graeber 2011, p. 249

- ^ "Karl Jaspers". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2006. Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- ^ Szakolczai, Arpad (2003). The Genesis of Modernity (First hardcover ed.). UK: Routledge. pp. 80–81. ISBN 0-415-25305-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Szakolczai, Arpad (2006). "Historical sociology". Encyclopedia of Social Theory. UK: Routledge. p. 251. ISBN 0-415-29046-5.

- ^ Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. (2012). "Introduction: The Axial Age Breakthrough in Ancient Greece". In Eisenstadt, Shmuel N. (ed.). The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations. SUNY series in Near Eastern Studies. SUNY Press. p. 31. ISBN 978-1438401942. Retrieved 2015-06-28.

The emergence of this specific type of Axial Age breakthrough was connected with the special mode of disintegration of the tribal communities and of construction of new collectivities and institutional complexes. [...] In the economic field, we find a growing occupational differentiation between the economic ties to the land and the urban vocations, be they in trade, craft, industry, or the ritual and educational fields. This phenomenon was also very closely connected with the development of many free economic resources—partially even land and manpower resources—not bound to ascriptive social units, the concomitant development of widespread internal and external, relatively free, market activities, and the accumulation of relatively mobile capital.

- ^ Armstrong 2006.

- ^ Strath, Bo (2005). "Axial Transformations". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved 2006-06-14.

- ^ Lambert, Yves (1999). "Religion in Modernity as a New Axial Age: Secularization or New Religious Forms?". Sociology of Religion. 60 (3): 303–333. doi:10.2307/3711939. JSTOR 3711939.

- ^ MacCulloch, Diarmaid (17 March 2006). "The axis of goodness". The Guardian.

- ^ Provan 2013.

- ^ Stephen K. Sanderson (2018). Religious Evolution and the Axial Age: From Shamans to Priests to Prophets (Scientific Studies of Religion: Inquiry and Explanation), Bloomsbury Academic.

Bibliography[]

- Armstrong, Karen (2006), The Great Transformation: The Beginning of our Religious Traditions (1st ed.), New York: Knopf, ISBN 0-676-97465-1. A semi-historic description of the events and milieu of the Axial Age.

- Graeber, David (2011), Debt: The First 5000 Years, Brooklyn: Melville House Press.

- Jaspers, Karl (1953), The Origin and Goal of History, Bullock, Michael (Tr.) (1st English ed.), London: Routledge & Keegan Paul, LCCN 53001441. Originally published as Jaspers, Karl (1949), Vom Ursprung und Ziel der Geschichte [The origin and goal of History] (in German) (1st ed.), München: Piper, LCCN 49057321.

- Provan, Iain (2013), Convenient Myths: The Axial Age, Dark Green Religion, and the World That Never Was, Waco: Baylor University Press, ISBN 978-1602589964.

- Eisenstadt, S. N. (Ed.). (1986). The Origins and Diversity of Axial Age Civilizations. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0887060960

- Hans Joas and Robert N. Bellah (Eds), (2012), The Axial Age and Its Consequences, Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0674066496

- Halton, Eugene (2014), From the Axial Age to the Moral Revolution: John Stuart-Glennie, Karl Jaspers, and a New Understanding of the Idea, New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-349-49487-3

Further reading[]

- "Wisdom, Revelation and Doubt: Perspectives on the First Millennium BC", Daedalus, Spring 1975.

- Eisenstadt, Shmuel (1982), "The Axial Age: The Emergence of Transcendental Visions and the Rise of Clerics", European Journal of Sociology, 23 (2): 294–314, doi:10.1017/s0003975600003908.

- Yves Lambert (1999). "Religion in Modernity as a New Axial Age: Secularization or New Religious Forms?". Oxford University Press: Sociology of Religion Vol. 60 No. 3. pp. 303–333. A general model of analysis of the relations between religion and modernity, where modernity is conceived as a new axial age.

- Rodney Stark (2007). Discovering God: A New Look at the Origins of the Great Religions. NY: HarperOne.

- Gore Vidal (1981). Creation. NY: Random House. A novel narrated by the fictional grandson of Zoroaster in 445 BCE, describing encounters with the central figures of the Axial Age during his travels.

- (2009). : The Political Origins of Environmental Degradation and the Environmental Origins of Axial Religions; China, Japan, Europe Lambert. Dr. Whitaker's research received a grant award from the U.S. National Science Foundation in Association with the American Sociological Association.

External links[]

- The Axial Age and Its Consequences, a 2008 conference in Erfurt, DE.

- Historical eras

- Ancient philosophy

- Religion in ancient history

- Iron Age