History of Buddhism

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

|

|

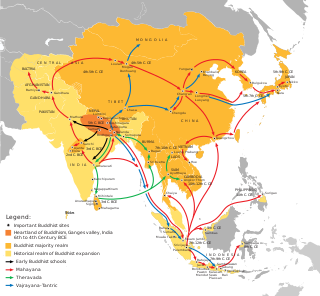

The history of Buddhism spans from the 6th century BCE to the present. Buddhism arose in the eastern part of Ancient India, in and around the ancient Kingdom of Magadha (now in Bihar, India), and is based on the teachings of Siddhārtha Gautama. The religion evolved as it spread from the northeastern region of the Indian subcontinent through Central, East, and Southeast Asia. At one time or another, it influenced most of the Asian continent. The history of Buddhism is also characterized by the development of numerous movements, schisms, and schools, among them the Theravāda, Mahāyāna and Vajrayāna traditions, with contrasting periods of expansion and retreat.

Life of the Buddha[]

Siddhārtha Gautama was the historical founder of Buddhism. The early sources state he was born in the small Shakya (Pali: Sakka) Republic, which was part of the Kosala realm of ancient India, now in modern-day Nepal.[2] He is thus also known as the Shakyamuni (literally: "The sage of the Shakya clan"). The republic was ruled by a council of household heads, and Gautama was born to one of these elites so that he described himself as a Kshatriya when talking to Brahmins.[2] The Early Buddhist Texts contain no continuous life of the Buddha, only later after 200 BCE were various "biographies" with much mythological embellishment written.[3] All texts agree however that Gautama renounced the householder life and lived as a sramana ascetic for some time studying under various teachers, before attaining nirvana (extinguishment) and bodhi (awakening) through meditation.

For the remaining 45 years of his life, he traveled the Gangetic Plain of north-central India (the region of the Ganges/Ganga river and its tributaries), teaching his doctrine to a diverse range of people from different castes and initiating monks into his order. The Buddha sent his disciples to spread the teaching across India. He also initiated an order of nuns.[4] He urged his disciples to teach in the local language or dialects.[5] He spent a lot of his time near the cities of Sāvatthī, Rājagaha and Vesālī (Skt. Śrāvastī, Rājagrha, Vāiśalī).[4] By the time of his death at 80, he had thousands of followers.

The years following the death of the Buddha saw the emergence of many movements during the next 400 years: first the schools of Nikaya Buddhism, of which only Theravada remains today, and then the formation of Mahayana and Vajrayana, pan-Buddhist sects based on the acceptance of new scriptures and the revision of older techniques.

Followers of Buddhism, called Buddhists in English, referred to themselves as Sakyan-s or Sakyabhiksu in ancient India.[6][7] Buddhist scholar Donald S. Lopez asserts they also used the term Bauddha,[8] although scholar Richard Cohen asserts that that term was used only by outsiders to describe Buddhists.[9]

Buddhism Early Ages[]

After the death of the Buddha, the Buddhist sangha (monastic community) remained centered on the Ganges valley, spreading gradually from its ancient heartland. The canonical sources record various councils, where the monastic Sangha recited and organized the orally transmitted collections of the Buddha's teachings and settled certain disciplinary problems within the community. Modern scholarship has questioned the accuracy and historicity of these traditional accounts.[10]

The first Buddhist council is traditionally said to have been held just after Buddha's Parinirvana, and presided over by Mahākāśyapa, one of His most senior disciples, at Rājagṛha (today's Rajgir) with the support of king Ajāthaśatru. According to Charles Prebish, almost all scholars have questioned the historicity of this first council.[11]

After an initial period of unity, divisions in the sangha or monastic community led to the first schism of the sangha into two groups: the Sthavira (Elders) and Mahasamghika (Great Sangha). Most scholars agree that the schism was caused by disagreements over points of vinaya (monastic discipline).[12] Over time, these two monastic fraternities would further divide into various Early Buddhist Schools.

The Sthaviras gave birth to a large number of influential schools including the Sarvāstivāda, the Pudgalavāda (also known as Vatsīputrīya), the Dharmaguptakas and the Vibhajyavāda (the Theravādins being descended from these).

The Mahasamghikas meanwhile also developed their own schools and doctrines early on, which can be seen in texts like the Mahavastu, associated with the Lokottaravāda, or ‘Transcendentalist’ school, who might be the same as the Ekavyāvahārikas or "One-utterancers".[13] This school has been seen as foreshadowing certain Mahayana ideas, especially due to their view that all of Gautama Buddha's acts were "transcendental" or "supramundane", even those performed before his Buddhahood.[13]

In the third century BCE, some Buddhists began introducing new systematized teachings called Abhidharma, based on previous lists or tables (Matrka) of main doctrinal topics.[14] Unlike the Nikayas, which were prose sutras or discourses, the Abhidharma literature consisted of systematic doctrinal exposition and often differed across the Buddhist schools who disagreed on points of doctrine.[14] Abhidharma sought to analyze all experience into its ultimate constituents, phenomenal events or processes called dharmas.

The Mallas were an ancient Indian republic (Gaṇa sangha) that constituted one of the solasa (sixteen) Mahajanapadas (great realms) of ancient India as mentioned in the Anguttara Nikaya.[15]

Mauryan empire (322–180 BCE)[]

The Maurya Empire under Emperor Aśoka was the world's first major Buddhist state. It established free hospitals and free education and promoted human rights.

The words "Bu-dhe" (