Rhythm and blues

| Rhythm and blues | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins |

|

| Cultural origins | 1940s–1950s, U.S. |

| Derivative forms |

|

| Subgenres | |

| |

| Local scenes | |

| |

Rhythm and blues, often abbreviated as R&B or R'n'B,[1] is a genre of popular music that originated in African-American communities in the 1940s.[2] The term was originally used by record companies to describe recordings marketed predominantly to urban African Americans, at a time when "urbane, rocking, jazz based music with a heavy, insistent beat" was becoming more popular.[3] In the commercial rhythm and blues music typical of the 1950s through the 1970s, the bands usually consisted of piano, one or two guitars, bass, drums, one or more saxophones, and sometimes background vocalists. R&B lyrical themes often encapsulate the African-American experience of pain and the quest for freedom and joy,[4] as well as triumphs and failures in terms of relationships, economics, and aspirations.

The term "rhythm and blues" has undergone a number of shifts in meaning. In the early 1950s, it was frequently applied to blues records.[5] Starting in the mid-1950s, after this style of music contributed to the development of rock and roll, the term "R&B" became used to refer to music styles that developed from and incorporated electric blues, as well as gospel and soul music. In the 1960s, several British rock bands such as the Rolling Stones, the Who and the Animals were referred to and promoted as being R&B bands; posters for the Who's residency at the Marquee Club in 1964 contained the slogan, "Maximum R&B".[6] Their mix of rock and roll and R&B is now known as "British rhythm and blues". By the end of the 1970s, the term "rhythm and blues" had changed again and was used as a blanket term for soul and funk. In the late 1980s, a newer style of R&B developed, becoming known as "contemporary R&B". It combines rhythm and blues with elements of pop, soul, funk, disco, hip hop, and electronic music.

Etymology, definitions and description[]

Although Jerry Wexler of Billboard magazine is credited with coining the term "rhythm and blues" as a musical term in the United States in 1948,[7] the term was used in Billboard as early as 1943.[8][9] It replaced the term "race music", which originally came from within the black community, but was deemed offensive in the postwar world.[10][11] The term "rhythm and blues" was used by Billboard in its chart listings from June 1949 until August 1969, when its "Hot Rhythm & Blues Singles" chart was renamed as "Best Selling Soul Singles".[12] Before the "Rhythm and Blues" name was instated, various record companies had already begun replacing the term "race music" with "sepia series".[13]

Writer and producer Robert Palmer defined rhythm & blues as "a catchall term referring to any music that was made by and for black Americans".[14] He has used the term "R&B" as a synonym for jump blues.[15] However, AllMusic separates it from jump blues because of R&B's stronger gospel influences.[16] Lawrence Cohn, author of Nothing but the Blues, writes that "rhythm and blues" was an umbrella term invented for industry convenience. According to him, the term embraced all black music except classical music and religious music, unless a gospel song sold enough to break into the charts.[10] Well into the 21st century, the term R&B continues in use (in some contexts) to categorize music made by black musicians, as distinct from styles of music made by other musicians.

In the commercial rhythm and blues music typical of the 1950s through the 1970s, the bands usually consisted of piano, one or two guitars, bass, drums, and saxophone. Arrangements were rehearsed to the point of effortlessness and were sometimes accompanied by background vocalists. Simple repetitive parts mesh, creating momentum and rhythmic interplay producing mellow, lilting, and often hypnotic textures while calling attention to no individual sound. While singers are emotionally engaged with the lyrics, often intensely so, they remain cool, relaxed, and in control. The bands dressed in suits, and even uniforms, a practice associated with the modern popular music that rhythm and blues performers aspired to dominate. Lyrics often seemed fatalistic, and the music typically followed predictable patterns of chords and structure.[17]

One publication of the Smithsonian Institution provided this summary of the origins of the genre in 2016.

"A distinctly African American music drawing from the deep tributaries of African American expressive culture, it is an amalgam of jump blues, big band swing, gospel, boogie, and blues that was initially developed during a thirty-year period that bridges the era of legally sanctioned racial segregation, international conflicts, and the struggle for civil rights".[18]

The term "rock and roll" had a strong sexual connotation in jump blues and R&B, but when DJ Alan Freed referred to rock and roll on mainstream radio in the mid-1950s, "the sexual component had been dialled down enough that it simply became an acceptable term for dancing".[19]

History[]

Precursors[]

The great migration of Black Americans to the urban industrial centers of Chicago, Detroit, New York City, Los Angeles and elsewhere in the 1920s and 1930s created a new market for jazz, blues, and related genres of music. These genres of music were often performed by full-time musicians, either working alone or in small groups. The precursors of rhythm and blues came from jazz and blues, which overlapped in the late-1920s and 1930s through the work of musicians such as the Harlem Hamfats, with their 1936 hit "Oh Red", as well as Lonnie Johnson, Leroy Carr, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, and T-Bone Walker. There was also increasing emphasis on the electric guitar as a lead instrument, as well as the piano and saxophone.[20]

Late 1940s[]

In 1948, RCA Victor was marketing black music under the name "Blues and Rhythm". In that year, Louis Jordan dominated the top five listings of the R&B charts with three songs, and two of the top five songs were based on the boogie-woogie rhythms that had come to prominence during the 1940s.[21] Jordan's band, the Tympany Five (formed in 1938), consisted of him on saxophone and vocals, along with musicians on trumpet, tenor saxophone, piano, bass and drums.[22][23] Lawrence Cohn described the music as "grittier than his boogie-era jazz-tinged blues".[10]:173 Robert Palmer described it as "urbane, rocking, jazz-based music with a heavy, insistent beat".[3] Jordan's music, along with that of Big Joe Turner, Roy Brown, Billy Wright, and Wynonie Harris, is now also referred to as jump blues. Already Paul Gayten, Roy Brown, and others had had hits in the style now referred to as rhythm and blues. In 1948, Wynonie Harris's remake of Brown's 1947 recording "Good Rockin' Tonight" reached number two on the charts, following band leader Sonny Thompson's "Long Gone" at number one.[24][25]

In 1949, the term "Rhythm and Blues" replaced the Billboard category Harlem Hit Parade.[10] Also in that year, "The Huckle-Buck", recorded by band leader and saxophonist Paul Williams, was the number one R&B tune, remaining on top of the charts for nearly the entire year. Written by musician and arranger Andy Gibson, the song was described as a "dirty boogie" because it was risque and raunchy.[26] Paul Williams and His Hucklebuckers' concerts were sweaty riotous affairs that got shut down on more than one occasion. Their lyrics, by Roy Alfred (who later co-wrote the 1955 hit "(The) Rock and Roll Waltz"), were mildly sexually suggestive, and one teenager from Philadelphia said "That Hucklebuck was a very nasty dance".[27][28] Also in 1949, a new version of a 1920s blues song, "Ain't Nobody's Business" was a number four hit for Jimmy Witherspoon, and Louis Jordan and the Tympany Five once again made the top five with "Saturday Night Fish Fry".[29] Many of these hit records were issued on new independent record labels, such as Savoy (founded 1942), King (founded 1943), Imperial (founded 1945), Specialty (founded 1946), Chess (founded 1947), and Atlantic (founded 1948).[20]

Afro-Cuban rhythmic influence[]

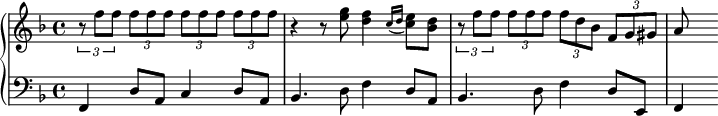

African American music began incorporating Afro-Cuban rhythmic motifs in the 1800s with the popularity of the Cuban contradanza (known outside of Cuba as the habanera).[30] The habanera rhythm can be thought of as a combination of tresillo and the backbeat.

For the more than a quarter-century in which the cakewalk, ragtime and proto-jazz were forming and developing, the Cuban genre habanera exerted a constant presence in African American popular music.[31] Jazz pioneer Jelly Roll Morton considered the tresillo/habanera rhythm (which he called the Spanish tinge) to be an essential ingredient of jazz.[32] There are examples of tresillo-like rhythms in some African American folk music such as the hand-clapping and foot-stomping patterns in ring shout, post-Civil War drum and fife music, and New Orleans second line music.[33] Wynton Marsalis considers tresillo to be the New Orleans "clave" (although technically, the pattern is only half a clave).[34] Tresillo is the most basic duple-pulse rhythmic cell in Sub-Saharan African music traditions, and its use in African American music is one of the clearest examples of African rhythmic retention in the United States.[35] The use of tresillo was continuously reinforced by the consecutive waves of Cuban music, which were adopted into North American popular culture. In 1940 Bob Zurke released "Rhumboogie," a boogie-woogie with a tresillo bass line, and lyrics proudly declaring the adoption of Cuban rhythm:

Harlem's got a new rhythm, man it's burning up the dance floors because it's so hot! They took a little rhumba rhythm and added boogie-woogie and now look what they got! Rhumboogie, it's Harlem's new creation with the Cuban syncopation, it's the killer! Just plant your both feet on each side. Let both your hips and shoulder glide. Then throw your body back and ride. There's nothing like rhumbaoogie, rhumboogie, boogie-woogie. In Harlem or Havana, you can kiss the old Savannah. It's a killer![36]

Although originating in the metropolis at the mouth of the Mississippi River, New Orleans blues, with its Afro-Caribbean rhythmic traits, is distinct from the sound of the Mississippi Delta blues.[37] In the late 1940s, New Orleans musicians were especially receptive to Cuban influences precisely at the time when R&B was first forming.[38] The first use of tresillo in R&B occurred in New Orleans. Robert Palmer recalls:

New Orleans producer-bandleader Dave Bartholomew first employed this figure (as a saxophone-section riff) on his own 1949 disc "Country Boy" and subsequently helped make it the most over-used rhythmic pattern in 1950s rock 'n' roll. On numerous recordings by Fats Domino, Little Richard and others, Bartholomew assigned this repeating three-note pattern not just to the string bass, but also to electric guitars and even baritone sax, making for a very heavy bottom. He recalls first hearing the figure – as a bass pattern on a Cuban disc.[39]

In a 1988 interview with Palmer, Bartholomew (who had the first R&B studio band),[40] revealed how he initially superimposed tresillo over swing rhythm:

I heard the bass playing that part on a 'rumba' record. On 'Country Boy' I had my bass and drums playing a straight swing rhythm and wrote out that 'rumba' bass part for the saxes to play on top of the swing rhythm. Later, especially after rock 'n' roll came along, I made the 'rumba' bass part heavier and heavier. I'd have the string bass, an electric guitar and a baritone all in unison.[41]

Bartholomew referred to the Cuban son by the misnomer rumba, a common practice of that time. Fats Domino's "Blue Monday," produced by Bartholomew, is another example of this now classic use of tresillo in R&B. Bartholomew's 1949 tresillo-based "Oh Cubanas" is an attempt to blend African American and Afro-Cuban music. The word mambo, larger than any of the other text, is placed prominently on the record label. In his composition "Misery," New Orleans pianist Professor Longhair plays a habanera-like figure in his left hand.[citation needed] The deft use of triplets is a characteristic of Longhair's style.

Gerhard Kubik notes that with the exception of New Orleans, early blues lacked complex polyrhythms, and there was a "very specific absence of asymmetric time-line patterns (key patterns) in virtually all early-twentieth-century African American music ... only in some New Orleans genres does a hint of simple time line patterns occasionally appear in the form of transient so-called 'stomp' patterns or stop-time chorus. These do not function in the same way as African timelines."[42] In the late 1940s, this changed somewhat when the two-celled time line structure was brought into the blues. New Orleans musicians such as Bartholomew and Longhair incorporated Cuban instruments, as well as the clave pattern and related two-celled figures in songs such as "Carnival Day," (Bartholomew 1949) and "Mardi Gras In New Orleans" (Longhair 1949). While some of these early experiments were awkward fusions, the Afro-Cuban elements were eventually integrated fully into the New Orleans sound.

Robert Palmer reports that, in the 1940s, Professor Longhair listened to and played with musicians from the islands and "fell under the spell of Perez Prado's mambo records."[43] He was especially enamored with Afro-Cuban music. Michael Campbell states: "Professor Longhair's influence was ... far-reaching. In several of his early recordings, Professor Longhair blended Afro-Cuban rhythms with rhythm and blues. The most explicit is 'Longhair's Blues Rhumba,' where he overlays a straightforward blues with a clave rhythm."[44] Longhair's particular style was known locally as rumba-boogie.[45] In his "Mardi Gras in New Orleans," the pianist employs the 2–3 clave onbeat/offbeat motif in a rumba boogie "guajeo".[46]

The syncopated, but straight subdivision feel of Cuban music (as opposed to swung subdivisions) took root in New Orleans R&B during this time. Alexander Stewart states that the popular feel was passed along from "New Orleans—through James Brown's music, to the popular music of the 1970s," adding: "The singular style of rhythm & blues that emerged from New Orleans in the years after World War II played an important role in the development of funk. In a related development, the underlying rhythms of American popular music underwent a basic, yet the generally unacknowledged transition from triplet or shuffle feel to even or straight eighth notes.[47] Concerning the various funk motifs, Stewart states that this model "... is different from a time line (such as clave and tresillo) in that it is not an exact pattern, but more of a loose organizing principle."[48]

Johnny Otis released the R&B mambo "Mambo Boogie" in January 1951, featuring congas, maracas, claves, and mambo saxophone guajeos in a blues progression.[49] Ike Turner recorded "Cubano Jump" (1954) an electric guitar instrumental, which is built around several 2–3 clave figures, adopted from the mambo. The Hawketts, in "Mardi Gras Mambo" (1955) (featuring the vocals of a young Art Neville), make a clear reference to Perez Prado in their use of his trademark "Unhh!" in the break after the introduction.[50]

Ned Sublette states: "The electric blues cats were very well aware of Latin music, and there was definitely such a thing as rhumba blues; you can hear Muddy Waters and Howlin' Wolf playing it."[51] He also cites Otis Rush, Ike Turner and Ray Charles, as R&B artists who employed this feel.[51]

The use of clave in R&B coincided with the growing dominance of the backbeat, and the rising popularity of Cuban music in the U.S. In a sense, clave can be distilled down to tresillo (three-side) answered by the backbeat (two-side).[52]

The "Bo Diddley beat" (1955) is perhaps the first true fusion of 3–2 clave and R&B/rock 'n' roll. Bo Diddley has given different accounts of the riff's origins. Sublette asserts: "In the context of the time, and especially those maracas [heard on the record], 'Bo Diddley' has to be understood as a Latin-tinged record. A rejected cut recorded at the same session was titled only 'Rhumba' on the track sheets."[51] Johnny Otis's "Willie and the Hand Jive" (1958) is another example of this successful blend of 3–2 claves and R&B. Otis used the Cuban instruments claves and maracas on the song.

Afro-Cuban music was the conduit by which African American music was "re-Africanized," through the adoption of two-celled figures like clave and Afro-Cuban instruments like the conga drum, bongos, maracas and claves. According to John Storm Roberts, R&B became the vehicle for the return of Cuban elements into mass popular music.[53] Ahmet Ertegun, producer for Atlantic Records, is reported to have said that "Afro-Cuban rhythms added color and excitement to the basic drive of R&B."[54] As Ned Sublette points out though: "By the 1960s, with Cuba the object of a United States embargo that still remains in effect today, the island nation had been forgotten as a source of music. By the time people began to talk about rock and roll as having a history, Cuban music had vanished from North American consciousness."[55]

Early to mid-1950s[]

At first, only African Americans were buying R&B discs. According to Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records, sales were localized in African-American markets; there was no white sales nor white radio play. During the early 1950s, more white teenagers started to become aware of R&B and to purchase the music. For example, 40% of 1952 sales at Dolphin's of Hollywood record shop, located in an African-American area of Los Angeles, were to whites. Eventually, white teens across the country turned their music taste towards rhythm and blues.[56]

Johnny Otis, who had signed with the Newark, New Jersey-based Savoy Records, produced many R&B hits in 1951, including: "Double Crossing Blues", "Mistrustin' Blues" and "Cupid's Boogie", all of which hit number one that year. Otis scored ten top ten hits that year. Other hits include: "Gee Baby", "Mambo Boogie" and "All Nite Long".[57] The Clovers, a quintet consisting of a vocal quartet with accompanying guitarist, sang a distinctive-sounding combination of blues and gospel,[58] had the number five hit of the year with "Don't You Know I Love You" on Atlantic.[57][59][60] Also in July 1951, Cleveland, Ohio DJ Alan Freed started a late-night radio show called "The Moondog Rock Roll House Party" on WJW (850 AM).[61][62] Freed's show was sponsored by Fred Mintz, whose R&B record store had a primarily African American clientele. Freed began referring to the rhythm and blues music he played as "rock and roll".

In 1951, Little Richard Penniman began recording for RCA Records in the jump blues style of late 1940s stars Roy Brown and Billy Wright. However, it was not until he prepared a demo in 1954, that caught the attention of Specialty Records, that the world would start to hear his new, uptempo, funky rhythm and blues that would catapult him to fame in 1955 and help define the sound of rock 'n' roll. A rapid succession of rhythm and blues hits followed, beginning with "Tutti Frutti"[63] and "Long Tall Sally", which would influence performers such as James Brown,[64] Elvis Presley,[65] and Otis Redding.[66]

Ruth Brown on the Atlantic label, placed hits in the top five every year from 1951 through 1954: "Teardrops from My Eyes", "Five, Ten, Fifteen Hours", "(Mama) He Treats Your Daughter Mean" and "What a Dream".[58] Faye Adams's "Shake a Hand" made it to number two in 1952. In 1953, the R&B record-buying public made Willie Mae Thornton's original recording of Leiber and Stoller's "Hound Dog"[68] the number three hit that year. Ruth Brown was very prominent among female R&B stars; her popularity was most likely derived because of "her deeply rooted vocal delivery in African American tradition"[69] [70] That same year The Orioles, a doo-wop group, had the #4 hit of the year with "Crying in the Chapel".[71]

Fats Domino made the top 30 of the pop charts in 1952 and 1953, then the top 10 with "Ain't That a Shame".[72][73] Ray Charles came to national prominence in 1955 with "I Got a Woman".[74] Big Bill Broonzy said of Charles's music: "He's mixing the blues with the spirituals ... I know that's wrong."[10]:173

In 1954 the Chords' "Sh-Boom"[75] became the first hit to cross over from the R&B chart to hit the top 10 early in the year. Late in the year, and into 1955, "Hearts of Stone" by the Charms made the top 20.[76]

At Chess Records in the spring of 1955, Bo Diddley's debut record "Bo Diddley"/"I'm a Man" climbed to number two on the R&B charts and popularized Bo Diddley's own original rhythm and blues clave-based vamp that would become a mainstay in rock and roll.[77]

At the urging of Leonard Chess at Chess Records, Chuck Berry had reworked a country fiddle tune with a long history, entitled "Ida Red".[78] The resulting "Maybellene" was not only a number three hit on the R&B charts in 1955, but also reached into the top 30 on the pop charts. Alan Freed, who had moved to the much larger market of New York City in 1954, helped the record become popular with white teenagers. Freed had been given part of the writing credit by Chess in return for his promotional activities; a common practice at the time.[79]

R&B was also a strong influence on Rock and roll according to many sources, including an article in the Wall Street Journal in 1985 titled, "Rock! It's Still Rhythm and Blues". In fact, the author stated that the "two terms were used interchangeably", until about 1957. The other sources quoted in the article said that rock and roll combined R&B with pop and country music.[80]

Fats Domino was not convinced that there was any new genre. In 1957, he said: "What they call rock 'n' roll now is rhythm and blues. I’ve been playing it for 15 years in New Orleans".[81] According to Rolling Stone, "this is a valid statement ... all Fifties rockers, black and white, country born and city bred, were fundamentally influenced by R&B, the black popular music of the late Forties and early Fifties".[82]

Late 1950s[]

In 1956, an R&B "Top Stars of '56" tour took place, with headliners Al Hibbler, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, and Carl Perkins, whose "Blue Suede Shoes" was very popular with R&B music buyers.[83] Some of the performers completing the bill were Chuck Berry, Cathy Carr, Shirley & Lee, Della Reese, Sam "T-Bird" Jensen, the Cleftones, and the Spaniels with Illinois Jacquet's Big Rockin' Rhythm Band.[84] Cities visited by the tour included Columbia, South Carolina, Annapolis, Maryland, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Syracuse, Rochester and Buffalo, New York and other cities.[citation needed] In Columbia the concert ended with a near riot as Perkins began his first song as the closing act. Perkins is quoted as saying, "It was dangerous. Lot of kids got hurt.". In Annapolis 70,000 to 50,000 people tried to attend a sold-out performance with 8,000 seats. Roads were clogged for seven hours.[85] Filmmakers took advantage of the popularity of "rhythm and blues" musicians as "rock n roll" musicians beginning in 1956. Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Fats Domino, Big Joe Turner, the Treniers, the Platters, the Flamingos, all made it onto the big screen.[86]

Two Elvis Presley records made the R&B top five in 1957: "Jailhouse Rock"/"Treat Me Nice" at number one, and "All Shook Up" at number five, an unprecedented acceptance of a non-African American artist into a music category known for being created by blacks.[87] Nat King Cole, also a jazz pianist who had two hits on the pop charts in the early 1950s ("Mona Lisa" at number two in 1950 and "Too Young" at number one in 1951), had a record in the top five in the R&B charts in 1958, "Looking Back"/"Do I Like It".[88]

In 1959, two black-owned record labels, one of which would become hugely successful, made their debut: Sam Cooke's Sar, and Berry Gordy's Motown Records.[89] Brook Benton was at the top of the R&B charts in 1959 and 1960 with one number-one and two number-two hits.[90] Benton had a certain warmth in his voice that attracted a wide variety of listeners, and his ballads led to comparisons with performers such as Nat King Cole, Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett.[91] Lloyd Price, who in 1952 had a number one hit with "Lawdy Miss Clawdy" regained predominance with a version of "Stagger Lee" at number one and "Personality" at number five for in 1959.[92][93]

The white bandleader of the Bill Black Combo, Bill Black, who had helped start Elvis Presley's career and was Elvis's bassist in the 1950s, was popular with black listeners.[citation needed] Ninety percent of his record sales were from black people, and his "Smokie, Part 2" (1959) rose to the number one position on black music charts.[citation needed] He was once told that "a lot of those stations still think you're a black group because the sound feels funky and black."[citation needed] Hi Records did not feature pictures of the Combo on early records.[94]

1960s–1970s[]

Sam Cooke's number five hit "Chain Gang" is indicative of R&B in 1960, as is pop rocker Chubby Checker's number five hit "The Twist".[95][96] By the early 1960s, the music industry category previously known as rhythm and blues was being called soul music, and similar music by white artists was labeled blue eyed soul.[97][98] Motown Records had its first million-selling single in 1960 with the Miracles' "Shop Around",[99] and in 1961, Stax Records had its first hit with Carla Thomas's "Gee Whiz (Look at His Eyes)".[100][101] Stax's next major hit, The Mar-Keys' instrumental "Last Night" (also released in 1961) introduced the rawer Memphis soul sound for which Stax became known.[102] In Jamaica, R&B influenced the development of ska.[103][104] In 1969 black culture and rhythm and blues reached another great achievement when the Grammys first added the Rhythm and Blues category, giving academic recognition to the category.[citation needed]

By the 1970s, the term "rhythm and blues" was being used as a blanket term for soul, funk, and disco.[105]

1980s to present[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, hip-hop started to capture the imagination of America's youth. R&B started to become homogenized, with a group of high-profile producers responsible for most R&B hits. It was hard for R&B artists of the era to sell their music or even have their music heard because of the rise of hip-hop, but some adopted a "hip-hop" image, were marketed as such, and often featured rappers on their songs. Newer artists such as Usher, R. Kelly, Janet Jackson, TLC, Aaliyah, Destiny's Child, Tevin Campbell and Mary J. Blige, enjoyed success. L.A. Reid, the CEO of LaFace Records, was responsible for some of R&B's greatest successes in the 1990s in the form of Usher, TLC and Toni Braxton. Later, Reid successfully marketed Boyz II Men.[106] In 2004, 80% of the songs that topped the R&B charts, were also on top of the Hot 100. That period was the all-time peak for R&B and hip hop on the Billboard Hot 100, and on Top 40 Radio.[107] From about 2005 to 2013, R&B sales declined.[108] However; since 2010 Hip-Hop has started to take from the R&B sound choosing to adopt a softer smoother sound incorporating that of traditional R&B with rappers such as Drake who has opened an entire new door for the genre. This sound has gained in popularity and created great controversy for both hip-hop and R&B in how to identify it.[109]

Jews in the business end of rhythm and blues[]

According to the Jewish writer, music publishing executive, and songwriter Arnold Shaw, during the 1940s in the US there was generally little opportunity for Jews in the WASP-controlled realm of mass communications, but the music business was "wide open for Jews as it was for blacks."[110] Jews played a key role in developing and popularizing African American music, including rhythm and blues, and the independent record business was dominated by young Jewish men who promoted the sounds of black music.[111]

British rhythm and blues[]

British rhythm and blues and blues rock developed in the early 1960s, largely as a response to the recordings of American artists, often brought over by African American servicemen stationed in Britain, or seamen visiting ports such as London, Liverpool, Newcastle and Belfast.[112][113] Many bands, particularly in the developing London club scene, tried to emulate black rhythm and blues performers, resulting in a "rawer" or "grittier" sound than the more popular "beat groups".[114] Initially developing out of the jazz, skiffle and blues club scenes, early artists tended to focus on major blues performers and standard forms, particularly blues rock musician Alexis Korner,[115] who acted with members of the Rolling Stones, Colosseum, the Yardbirds, Manfred Mann, and the Graham Bond Organisation.[114] Although this interest in the blues would influence major British rock musicians, including Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor, Peter Green, John Mayall, Free, and Cream adopted an interest in a wider range of rhythm and blues styles.[114]

The Rolling Stones became the second most popular UK band (after The Beatles)[116] and led the "British Invasion" of the US pop charts.[114] The Rolling Stones covered Bobby Womack & the Valentinos'[117] song It's All Over Now", giving them their first UK number one in 1964.[118] Under the influence of blues and R&B, bands such as the Rolling Stones, the Yardbirds, and the Animals, and more jazz-influenced bands like the Graham Bond Organisation and Zoot Money had blue-eyed soul albums.[114] White R&B musicians popular in the UK included Steve Winwood, Frankie Miller, Scott Walker & the Walker Brothers, the Animals from Newcastle, [119] the Spencer Davis Group, and Van Morrison & Them from Belfast.[114] None of these bands exclusively played rhythm and blues, but it remained at the core of their early albums.[114]

Many British black musicians created the British R&B scene. These included Geno Washington, an American singer stationed in England with the Air Force. He was invited to join what became Geno Washington & the Ram Jam Band by guitarist Pete Gage in 1965 and enjoyed top 40 hit singles and two top 10 albums before the band split up in 1969.[120] Another American GI, Jimmy James, born in Jamaica, moved to London after two local number one hits with The Vagabonds in 1960 and built a strong reputation as a live act, releasing a live album and their debut, The New Religion, in 1966 and achieving moderate success with singles before the original Vagabonds broke up in 1970.[121] Champion Jack Dupree was a New Orleans blues and boogie woogie pianist who toured Europe and settled there from 1960, living in Switzerland and Denmark, then in Halifax, England in the 1970s and 1980s, before finally settling in Germany.[122] From the '70s to '80s, Carl Douglas, Hot Chocolate, Delegation, Junior, Central Line, Princess, and Jacki Graham gained hits on pop or R&B chart. The music of the British mod subculture grew out of rhythm and blues and later soul performed by artists who were not available to the small London clubs where the scene originated.[123] In the late '60s, The Who performed American R&B songs such as the Motown hit "Heat Wave", a song which reflected the young mod lifestyle.[123] Many of these bands enjoyed national success in the UK, but found it difficult to break into the American music market.[123] The British R&B bands produced music which was very different in tone from that of African-American artists, often with more emphasis on guitars and sometimes also with greater energy.[114]

See also[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Rhythm and blues |

- List of artists who reached number one on the Billboard R&B chart

- List of number-one rhythm and blues hits (United States)

- Music of the United States

References[]

- ^ Don Michael Randel (1999). The Harvard Concise Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Harvard University Press. p. 560. ISBN 978-0-674-00084-1.

- ^ The new blue music: changes in rhythm & blues, 1950–1999, p. 172.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Palmer, Robert (July 29, 1982). Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta (paperback ed.). Penguin. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-14-006223-6.

- ^ Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1993.[page needed]

- ^ The new blue music: changes in rhythm & blues, 1950–1999, p. 8

- ^ "The Who Maximum R&B Live at Leeds New Musical Express Cover" Archived September 9, 2019, at the Wayback Machine, Myvintagegeneration.com

- ^ Sacks, Leo (August 29, 1993). "The Soul of Jerry Wexler". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 12, 2007. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- ^ Night Club Reviews Billboard February 27, 1943 page 12

- ^ Vaudeville reviews Billboard March 4, 1944 page 28

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Cohn, Lawrence; Aldin, Mary Katherine; Bastin, Bruce (September 1993). Nothing but the Blues: The Music and the Musicians. Abbeville Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-1-55859-271-1.

- ^ Jerry Wexler, famed record producer, dies at 91, Nekesa Mumbi Moody, AP Music Writer, Dallas Morning News, August 15, 2008

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (1996). Top R&B/Hip-Hop Singles: 1942–1995. Record Research. p. xii. ISBN 0-89820-115-2.

- ^ Rye, Howard. "Rhythm and Blues". Oxford Music Online. Archived from the original on May 11, 2020. Retrieved July 20, 2014.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (September 19, 1995). Rock & Roll: An Unruly History. Harmony. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-517-70050-1.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (May 21, 1981). Deep Blues: A Musical and Cultural History of the Mississippi Delta. Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0-670-49511-5.

- ^ Rhythm and blues at AllMusic

- ^ Morrison, Craig (1952). "Go Cat Go!" University of Illinois Press. page 30. ISBN 0-252-06538-7

- ^ "Tell It Like It Is: A History of Rhythm and Blues". Archived from the original on March 9, 2021. Retrieved February 21, 2021.

- ^ "The unexpected origins of music's most well-used terms". BBC. October 12, 2018. Archived from the original on January 26, 2019. Retrieved February 22, 2021.

its meaning covering both sex and dancing

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Tad Richards, "Rhythm and Blues", St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture". Findarticles.com. January 29, 2002. Archived from the original on December 7, 2009. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs 1947". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on May 28, 2009. Retrieved January 5, 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Louis Jordan at All About Jazz". Allaboutjazz.com. Archived from the original on May 13, 2009. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ "The Vocal Group Harmony Web Site". Vocalgroupharmony.com. Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs 1948". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ Biography for Andy Gibson at IMDb

- ^ "Hucklebuck!". Wfmu.org. Archived from the original on May 7, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Hucklebuck!". Wfmu.org. December 15, 1948. Archived from the original on April 4, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "– Year End Charts – Year-end Singles – Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs". Billboard.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "[Afro]-Latin rhythms have been absorbed into black American styles far more consistently than into white popular music, despite Latin music's popularity among whites" (Roberts The Latin Tinge 1979: 41).

- ^ Roberts, John Storm (1999: 16) Latin Jazz. New York: Schirmer Books.

- ^ Morton, "Jelly Roll" (1938: Library of Congress Recording): "Now in one of my earliest tunes, 'New Orleans Blues,' you can notice the Spanish tinge. In fact, if you can't manage to put tinges of Spanish in your tunes, you will never be able to get the right seasoning, I call it, for jazz." The Complete Recordings By Alan Lomax.

- ^ Kubik, Gerhard (1999: 52). Africa and the Blues. Jackson, MI: University Press of Mississippi.

- ^ "Wynton Marsalis part 2." 60 Minutes. CBS News (June 26, 2011).

- ^ Schuller, Gunther (1968: 19) "It is probably safe to say that by and large the simpler African rhythmic patterns survived in jazz ... because they could be adapted more readily to European rhythmic conceptions. Some survived, others were discarded as the Europeanization progressed. It may also account for the fact that patterns such as [tresillo have] ... remained one of the most useful and common syncopated patterns in jazz." Early Jazz; Its Roots and Musical Development. New York: Oxford Press.

- ^ "RHUMBOOGIE – Lyrics – International Lyrics Playground". Lyricsplayground.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1981: 247). Deep Blues. New York: Penguin Books.

- ^ "Rhythm and blues-influenced by Afro-Cuban music first surfaced in New Orleans." Campbell, Michael, and James Brody (2007: 83). Rock and Roll: An Introduction. Schirmer. ISBN 0534642950

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1995: 60). An Unruly History of Rock & Roll. New York: Oxford University Press.

- ^ Sublette, Ned (2007). "The Kingsmen and the Cha-cha-chá". In Eric Weisbard (ed.). Listen Again: A Momentary History of Pop Music. Duke University Press. p. 82. ISBN 0822340410.

- ^ Dave Bartholomew quoted by Palmer, Robert (1988: 27) "The Cuban Connection" Spin Magazine Nov.

- ^ Kubik (1999 p. 51).

- ^ Palmer, Robert (1979: 14). A Tale of Two Cities: Memphis Rock and New Orleans Roll. Brooklyn.

- ^ Campbell, Michael, and James Brody (2007: 83). Rock and Roll: An Introduction. Schirmer. ISBN 0534642950

- ^ Stewart, Alexander (2000: 298). "Funky Drummer: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music." Popular Music, v. 19, n. 3. October 2000, p. 293-318.

- ^ Kevin Moore: "There are two common ways that the three-side [of clave] is expressed in Cuban popular music. The first to come into regular use, which David Peñalosa calls 'clave motif,' is based on the decorated version of the three-side of the clave rhythm. By the 1940s [there was] a trend toward the use of what Peñalosa calls the 'offbeat/onbeat motif.' Today, the offbeat/onbeat motif method is much more common." Moore (2011). Understanding Clave and Clave Changes p. 32. Santa Cruz, CA: Moore Music/Timba.com. ISBN 1466462302

- ^ Stewart (2000 p. 293).

- ^ Stewart (2000 p. 306).

- ^ Boggs, Vernon (1993 pp. 30–31). "Johnny Otis R&B/Mambo Pioneer" Latin Beat Magazine. v. 3 n. 9. Nov.

- ^ Stewart, Alexander (2000 p. 307). "Funky Drummer: New Orleans, James Brown and the Rhythmic Transformation of American Popular Music." Popular Music, v. 19, n. 3. October 2000, pp. 293–318.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Sublette 2007, p. 83

- ^ Peñalosa, David (2010 p. 174). The Clave Matrix; Afro-Cuban Rhythm: Its Principles and African Origins. Redway, California: Bembe Inc. ISBN 1-886502-80-3.

- ^ Roberts, John Storm (1999 p. 136).The Latin Tinge. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Roberts (1999: 137).

- ^ Sublette 2007, p. 69).

- ^ Szatmary, David P. (2014). Rockin' in Time. New Jersey: Pearson. p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "– Biography: Johnny Otis". Billboard.com. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gilliland 1969, show 3, track 2.

- ^ "The Vocal Groups". History-of-rock.com. Archived from the original on June 12, 2012. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Clovers Don't You Know I Love You & Other Favorites CD". Cduniverse.com. May 11, 2004. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ "Kevin Smith Library : Case Western Reserve University : Search Results : Mintz". Library.case.ueu. Archived from the original on February 3, 2014. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Buzzard Audio – The Buzzard: Inside the Glory Days of WMMS and Cleveland Rock Radio — A Memoir – Page 4". buzzardbook.wordpress.com. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved February 12, 2018.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 6, track 2.

- ^ White, Charles. (2003), p. 231. The Life and Times of Little Richard: The Authorised Biography. Omnibus Press.

- ^ White (2003), p. 227

- ^ White (2003), p. 231

- ^ "Ruth Brown, the Queen of R&B, was born 93 years ago today". Frank Beacham's Journal. Archived from the original on January 24, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 7, track 4.

- ^ Floyd, Samuel Jr. (1995). The Power of Black Music. Oxford University Press. p. 177.

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs 1953". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "The Orioles Record Label Shots". Archived from the original on July 8, 2008. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 6, track 3.

- ^ Go, Cat, Go! by Carl Perkins and David McGee 1996 pages 111 Hyperion Press ISBN 0-7868-6073-1

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 15.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 4, track 5.

- ^ Go, Cat, Go! by Carl Perkins and David McGee 1996 page 111 Hyperion Press ISBN 0-7868-6073-1

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 3, track 5.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 5, track 5.

- ^ "– Biography – Chuck Berry". Billboard.com. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Redd, Lawrence N. (March 1, 1985). "The Black Perspective in Music". Wall Street Journal. 13 (1): 31–47. JSTOR 1214792. Archived from the original on May 25, 2019. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

by Lawrence N. Redd

- ^ Leight, Elias (October 26, 2017). "Paul McCartney Remembers 'Truly Magnificent' Fats Domino". Rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on November 25, 2020. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (April 19, 1990). "The 50s: A Decade of Music That Changed the World". Rollingstone.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2021. Retrieved March 15, 2021.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel, The Billboard Book of TOP 40 R&B and Hip Hop Hits, Billboard Books, New York 2006 p. 451

- ^ "BLUES". Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved January 18, 2021.

- ^ Go, Cat, Go! by Carl Perkins and David McGee 1996 pp. 188, 210, 212–214 Hyperion Press ISBN 0-7868-6073-1

- ^ Don't Knock the Rock (1956), Rock Around the Clock (1956), Rock, Rock, Rock (1956), Rumble on the Docks (1956), Shake, Rattle & Rock (1956), The Girl Can't Help It (1956), Rock Baby, Rock It (1957), Untamed Youth (1957), Go, Johnny, Go! (1959)

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs 1957". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 22, tracks 3–4.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (September 19, 1995). Rock & Roll: An Unruly History. Harmony. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-517-70050-1.

- ^ "Brook Benton". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 25, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- ^ Simon, Tom. "Brook Benton Biography". Archived from the original on February 5, 2012. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Billboard.com – Year End Charts – Year-end Singles – Hot R&B;/Hip-Hop Songs". June 18, 2009. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ "Billboard.com – Year End Charts – Year-end Singles – Hot R&B;/Hip-Hop Songs". June 18, 2009. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ The Blue Moon Boys—The Story of Elvis Presley's Band. Ken Burke and Dan Griffin. 2006. Chicago Review Press. pp. 138, 139. ISBN 1-55652-614-8

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs 1959". Billboard. Archived from the original on June 18, 2009. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ "Hot R&B/Hip-Hop Songs 1960". Billboard. Archived from the original on December 11, 2007. Retrieved December 23, 2007.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 52.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (September 19, 1995). Rock & Roll: An Unruly History. Harmony. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-517-70050-1.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 25.

- ^ Palmer, Robert (September 19, 1995). Rock & Roll: An Unruly History. Harmony. p. 83,84. ISBN 978-0-517-70050-1.

- ^ "Sample of "Gee Whiz"". Music.barnesandnoble.com. Archived from the original on December 30, 2011. Retrieved May 21, 2014.

- ^ "Mar-Keys – Last Night – Billboard Top 100 – 1961 – Top Billboard – mp3 song hits download full albums in mp3". Mp3fiesta.com. Archived from the original on July 8, 2017. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Origins of Ska, Reggae and Dub Music". Potentbrew.com. August 3, 1999. Archived from the original on January 16, 2010. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ "The Beginning". Web.fccj.edu. Archived from the original on May 12, 2008. Retrieved January 7, 2010.

- ^ Cahoon, Brad (December 11, 2014). "Rhythm and Blues Music: Overview". New Georgia Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on February 1, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- ^ "THE CHANGING FACE OF R&B". www.bluesandsoul.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ "100 & Single: The R&B/Hip-Hop Factor In The Music Business's Endless Slump". Village Voice. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ says, ChgoSista. "The Sacrifice of R&B". Soul Train. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2015.

- ^ Vickie Cox Edmondson (July 18, 2008). "A preliminary review of competitive reactions in the hip‐hop music industry: Black American entrepreneurs in a new industry". Management Research News. 31 (9): 637–649. doi:10.1108/01409170810898536. ISSN 0140-9174.

- ^ Arnold Shaw (1978). Honkers and Shouters: The Golden Years of Rhythm and Blues. Collier Books. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-02-061760-0. Archived from the original on March 29, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Muchin, Andrew (August 1994). "How a Bunch of Upstart Jewish Independent Record Producers Helped Turn African American Music into a National Treasure". Moment Magazine. pp. 53–54. Archived from the original on March 29, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ R. F. Schwartz, How Britain Got the Blues: the Transmission and Reception of American Blues Style in the United Kingdom (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007), ISBN 0-7546-5580-6, p. 28.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1315–1316.

- ^ "Alexis Korner – Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 7, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 30.

- ^ "The Valentinos – Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Archived from the original on February 26, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2019.

- ^ Bill Wyman, Rolling With the Stones (DK Publishing, 2002), ISBN 0-7894-9998-3, p. 137.

- ^ Gilliland 1969, show 29, track 3.

- ^ J. Bush, "Geno Washington", Allmusic. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ A. Hamilton, "Jimmy James", Allmusic. Retrieved 29 July 2020.

- ^ T. Russell, The Blues: From Robert Johnson to Robert Cray (London: Carlton, 1997), ISBN 1-85868-255-X

- ^ Jump up to: a b c V. Bogdanov, C. Woodstra and S. T. Erlewine, All Music Guide to Rock: the Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul (Milwaukee, WI: Backbeat Books, 3rd edn., 2002), ISBN 0-87930-653-X, pp. 1321–1322.

Further reading and listening[]

- Gilliland, John (1969). "The Tribal Drum: The rise of rhythm and blues" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries.

- Guralnick, Peter. Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom. First ed. New York: Harper & Row, 1986. x, 438 p., ill., chiefly with b&w photos. ISBN 0-06-096049-3

- Rhythm and blues

- African-American culture

- African-American history

- African-American music

- African-American society