Richard Pynson

Richard Pynson (c.1449 – c.1529) was one of the first printers of English books. Born in Normandy he moved to London, where he became one of the leading printers of the generation following William Caxton. His books were printed to a high standard of craftsmanship, and his Morton Missal (1500) is regarded as among the finest books printed in England in the period.

Pynson was appointed King's Printer to Henry VII and Henry VIII, and printed and published much official legal material. In addition he produced a wide range of books, including the first printed cookery book in English, an illustrated edition of The Canterbury Tales, and the first English book to use roman type.

Life and career[]

Early years[]

Pynson was Norman by birth.[1][n 1] According to the antiquarian Joseph Ames, the official document (now lost) recording Pynson's subsequent English naturalisation, in about 1493, describes him as Richardus Pynson in partibus Normand oriund ("… originating in Norman parts").[3] The earliest presumed reference to him is in 1464, in a list of students enrolled at the University of Paris.[1] It is not known when he moved to London, but the historian H. R. Plomer established that a Richard Pynson was a glover near the City of London in 1482 in the same parish in which a man of that name is recorded as a printer and bookbinder in the 1490s, although there is no firm evidence that they are the same person.[4]

Where and with whom Pynson learned the craft of printing is unknown. Possibilities suggested by scholars over the years include apprenticeship to Guillaume Le Talleur in Rouen, or Jean du Pré in Paris, or John Lettou and William de Machlinia in London, or William Caxton in Westminster.[1] The bibliographer and historian of printing E. G. Duff, writing in 1896, commented that although Pynson wrote of Caxton as "my worshipful master",[n 2] it seemed unlikely that he was ever in the latter's employment.[2]

Pynson had begun his printing career by 1492, the year in which he printed Alexander Grammaticus's Doctrinale, his first dated book.[1][n 3] According to several sources, it is likely that he took over de Machlinia's business in 1490 after the latter's death, including "his tools, stock, possibly his press, and to a large extent his clientele".[6][7] During the first years, he worked in the parish of St Clement Danes just outside the city boundary at Temple Bar, but he moved east into the city in 1501, possibly because of xenophobic disturbances,[8] or perhaps simply "to be closer to the book trade, most of the leading men having their shops in the neighbourhood of St Paul's Cathedral".[9] He established himself at the sign of the George in Fleet Street, continuing at that address until his death.[2] Julian Notary is believed to have taken over Pynson's vacated premises at St Clement's.[10]

Later years[]

Pynson became King's Printer to Henry VII (and subsequently to Henry VIII) in 1506,[11] an office that carried not only great prestige but also an annuity of two pounds, later raised to four pounds.[12]

Pynson ran his printing business conservatively, not taking great risks or paying great attention to literary patronage, despite its importance in the early printing period.[13] He does not seem to have imported books, since his name does not appear on the Customs rolls.[14]

Of Pynson's employees, two are named in his will (dated 18 November 1529): John Snowe and Richard Withers.[15] Judging by this document he was well-off but not as wealthy as, for example, Wynkyn de Worde.[16] As a businessman he has been described as "a systematic, careful man of business";[17] as a printer he is credited with "a sense of style that raised him above other English printers of the fifteenth century".[18]

Pynson died in late 1529 or early 1530 at the age of 80 or 81.[1] He had been married twice and outlived both his wives. He was survived by a daughter, Margaret, whose husband saw the last book off Pynson's press to completion on 18 July 1530. Robert Redman, Pynson's chief (and according to Duff "rather unscrupulous")[2] rival in the publication of legal texts, and his successor as King's Printer, eventually took over his printing house and materials.[1]

Works[]

Pynson published some 400 titles during his career.[19] This was fewer than his rival, Wynkyn de Worde, but, according to Duff his books are "of a higher standard and better execution".[2] Between them, Pynson and de Worde published about two-thirds of all the books produced for the English market between 1500 and 1530.[19]

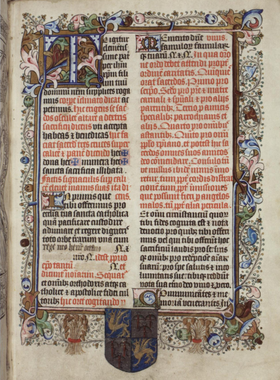

In 1496 Pynson issued an edition of the works of the Roman poet Terence, the first classic printed in London,[2] and in 1500 The Boke of Cokery, the first printed cookery book in English.[20] In the same year he produced the Morton Missal, printed in black and red and lavishly illuminated by hand, later called "the finest book printed in the fifteenth century in England".[21]

A considerable number of Pynson's books were law texts (such as statutes of the king and legal handbooks) and religious books, including Books of Hours, two further Missals), and Assertio septem sacramentorum adversus Martinum Lutherum (1521), Henry VIII's attack on the Protestant reformer, which gained the king the title of "Defender of the Faith" from the pope.[2]

In addition to his more serious publications, Pynson printed popular romances such as Sir Tryamour, the travel memoir Ways to Jerusalem by Sir John Mandeville, and, in 1509, a translation of the satirical The Ship of Fools by Sebastian Brant. In the last of these, Pynson introduced roman type to England, although it did not become the standard for vernacular printing during his lifetime.[22][n 4]

Notes, references and sources[]

Notes[]

- ^ "Pynson" was Norman French for "finch".[2]

- ^ In Pynson's introduction to his 1492 edition of The Canterbury Tales; in an article about this edition, Julie Gardham of the Glasgow University library suggests that this is an acknowledgment by Pynson of his indebtedness to Caxton's second edition of the poem, upon which Pynson's version was based.[5]

- ^ According to Pamela Neville-Sington in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, typographical evidence suggests that there were earlier publications, and, as printers were also publishers, Pynson commissioned the printing of two books from Le Tailleur in the early 1490s, both law books: Sir Thomas Liuleton's New Tenures and Nicholas Statham's Abridgement of Statutes.[1][6]

- ^ Roman type quickly became usual for Latin texts, but blackletter continued to be widely preferred for English;[22] England was the last western European nation to adopt roman type as the norm, and it was not until the early 17th century that it completely supplanted the old blackletter type.[23]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Neville-Sington, Pamela. Pynson, Richard (c. 1449–1529/30), printer", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Oxford University Press, 2008. Retrieved 24 October 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Duff, E. G. "Pynson, Richard", Dictionary of National Biography, 1896. Retrieved 25 October 2020 (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ Ames, p. 111

- ^ Plomer (1922), pp. 49–50

- ^ Gardham, Julie. "Geoffrey Chaucer" Archived 28 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Glasgow University Library, 2004. Retrieved 25 October 2020

- ^ Jump up to: a b Neville, p. 11

- ^ Duff, 1906, p. 56; and Plomer, 1925, pp. 160ff

- ^ Plomer, 1925, pp. 122–123.

- ^ Plomer, 1925, p. 65.

- ^ Clair, 1965, p. 41.

- ^ Neville, p. 13

- ^ Clair, 1965, p. 35.

- ^ Lathrop, p. 93

- ^ Hellinga, p. 140.

- ^ Plomer, 1903, p. 3.

- ^ Plomer, 1925, p. 145.

- ^ Bennett, p. 191

- ^ Chappell, p. 77.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Steinberg, p. 106

- ^ Oxford, p. 1

- ^ Airaksinen, p. 147

- ^ Jump up to: a b McKellar, Rebecca. "Ship of Fools" Archived 29 October 2020 at the Wayback Machine, Glasgow University Library, 2002. Retrieved 25 October 2020

- ^ Steinberg, pp. 169–170

Sources[]

Books[]

- Ames, Joseph (1810). Typographical Antiquities. London: W. Faden. OCLC 614434086.

- Bennett, H. S. (1952). English Books and Readers 1475–1557. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 18501246.

- Chappell, Warren (1980) [1970]. A Short History of the Printed Word. Boston: Nonpareil Books. OCLC 1151394821.

- Clair, Colin (1965). A History of Printing in Britain. London: Cassell. OCLC 1289677.

- Duff, E. Gordon (1906). The Printers, Stationers and Bookbinders of Westminster and London from 1476 to 1535. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. OCLC 1170373343.

- Hellinga, Lotte (1999). "Printing". In Lotte Hellinga; J. B. Trapp (eds.). The Cambridge History of the Book in Britain Vol III (1400–1557). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-57346-7.

- Oxford, A. W. (1913). English Cookery Books to the Year 1850. London and New York: H. Frowde, Oxford University Press. OCLC 252887531.

- Plomer, Henry R. (1903). Abstracts from the Wills of English Printers and Stationers from 1492 to 1630. London: Bibliographical Society. OCLC 457912515.

- Plomer, Henry R. (1925). Wynkyn de Worde and his Contemporaries from the Death of Caxton to 1535. London: Grafton. OCLC 867872633.

- Plomer, Henry R. (1927). "Great Britain and Ireland". In R. A. Peddie (ed.). Printing A Short History of the Art. London: Grafton. OCLC 1015734485.

- Steinberg, Sigfrid (1955). Five Hundred Years of Printing. Harmondsworth: Penguin. OCLC 186787961.

Journals[]

- Airaksinen, Katja (2009). "The Morton Missal: The Finest Incunable Made in England". Transactions of the Cambridge Bibliographical Society (XIV/2): 147–179. (subscription required)

- Lathrop, H. B. (September 1922). "The First English Printers and their Patrons". The Library: 69–96.(subscription required)

Thesis[]

- Neville, Pamela (1990). Richard Pynson, King’s Printer (1506–1529): Printing and Propaganda in Early Tudor England (PhD). London: University of London. OCLC 53651881.(subscription required)

Further reading[]

- Burger, Glenn (1988). A Lytell Cronycle: Richard Pynson's Translation (c 1520) of La Fleur des histoires de la terre d'Orient (c 1307). University of Toronto Press.

External links[]

- Works by or about Richard Pynson in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- 1448 births

- 1529 deaths

- English printers

- Printers of incunabula

- 16th-century English businesspeople

- 15th-century English people

- 16th-century printers