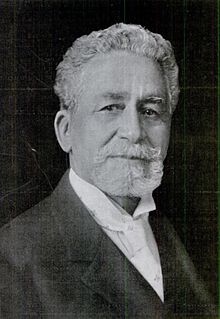

Richard Theodore Greener

Richard Theodore Greener | |

|---|---|

| |

| Dean of Howard Law School | |

| In office 1878–1880 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | January 30, 1844 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania |

| Died | May 2, 1922 (aged 78) Chicago, Illinois |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Children | Belle da Costa Greeneand 8 others |

| Alma mater | Phillips Academy Andover Oberlin College (did not graduate) Harvard University (A.B.) University of South Carolina (LL.B.) |

| Profession | Professor, Diplomat, Attorney |

Richard Theodore Greener (January 30, 1844 – May 2, 1922) was the first African American graduate of Harvard College and went on to become the dean of the Howard University School of Law.

Early life and education[]

Richard Greener was born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1844[1] and moved with his mother to Boston when he was approximately nine years old. He quit school in his mid-teens to earn money for his family, but one of his employers, Franklin B. Sanborn, helped him to enroll in preparatory school (Oberlin Academy) at Oberlin College.

He then enrolled at Phillips Academy and graduated in 1865. He studied at Oberlin College for three years before transferring to Harvard College where he earned a bachelor's degree in 1870. His admission to Harvard was "an experiment" by the administration and paved the way for many more Black Harvard graduates.[2]

While at Harvard, he earned the Bowdoin Prize for elocution twice.[3]

An article appeared in the Rochester Daily Democrat on August 16, 1869:

Richard Theodore Greener, a young colored man and a member of the senior class of Harvard College, is giving public readings in Philadelphia. Mr. Greener's history is that of a persevering young man who has succeeded in living down the prejudices against his race and color, and attaining by industry, ability, and good character, a position of which he may well feel proud. He was awarded last year, at Harvard College, the prize for reading, and this year he has drilled two young white men who have likewise obtained prizes in the same branch. His course at Harvard has throughout been honorable. He is the first colored youth who has ever passed through that college.[citation needed]

Academic career[]

After graduating from Harvard, Greener served as a principal at the Institute for Colored Youth in Philadelphia from September 1870 until December 1872. He succeeded Octavius V. Catto, who was shot in a riot. From January 1 to July 1, 1873, he was principal of the Sumner High School, a colored preparatory school in Washington, D.C.[4]

After leaving the Sumner School, Greener briefly took a job as associate editor of The New National Era in April 1873, working under editor Frederick Douglass.[4] He was also an associate editor for the National Encyclopedia for American Biography.[3]

University of South Carolina[]

In October 1873, Greener accepted the professorship of mental and moral philosophy at the University of South Carolina, where he was the university's first African-American faculty member.[5]

He also served as a librarian there helping to "reorganize and catalog the library's holdings which were in disarray after the Civil War" and wrote a monograph on the rare books of the library.[6] His responsibilities included assisting in the departments of Latin and Greek and teaching classes in International Law and the Constitution of the United States.[4]

In 1875, Greener became the first African American to be elected a member of the American Philological Association, the primary academic society for classical studies in North America.

Howard Law School[]

Greener graduated from the law school at the University of South Carolina and was admitted to practice in the Supreme Court of South Carolina on December 20, 1876.[4]

In June 1877, following the end of Reconstruction in South Carolina, the University was closed by Wade Hampton III. Greener moved to Washington and was admitted to the Bar of the District of Columbia on April 14, 1877.[4] He took a position as a professor at Howard University Law School and served as dean from 1878 to 1880, succeeding John H. Cooke.[4][7]

He also worked on a number of famous legal cases. He was associate counsel of Jeremiah M. Wilson in the defense of Samuel L. Perry and of Martin I. Townsend in the defense of Johnson Chesnut Whittaker in a court of inquiry in April and May 1880 where Towsend and Greener successfully gained Whittaker release and the granting of a court-martial. Greener assisted Daniel Henry Chamberlain in Whittaker's defense during the court-martial.[4][clarification needed][further explanation needed]

Public service and activism[]

From 1876 to 1879, Greener represented South Carolina in the Union League of America and was president of the South Carolina Republican Association in 1887 and was active in freemasonry.[4] In 1875, Greener was appointed by the South Carolina Assembly to a commission to revise the South Carolina school system.

From 1880 until February 28, 1882, Greener served as a law clerk of the Comptroller of the United States Treasury.

In 1883, Greener and Frederick Douglass conducted a heated debate. Greener and the rising generation of black leaders advocated moving away from political parties and white allies, while Douglass denounced them as "croakers."[8] Greener, who nonetheless still respected Douglass' achievements, helped organize a major convention to present black grievances to the nation. Decades had passed since the Civil War, the Emancipation Proclamation, and years since the passage of the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, but these advances had been rolled back or left unenforced, while Jim Crow laws spread in the South. Greener joined younger black leaders in questioning Douglass, who remained loyal to the Republican Party that had first fought for Black freedom then abandoned them. Douglass accused Greener of writing anonymous attacks motivated by “ambition and jealousy” that charged the older leader with “trading off the colored vote of the country for office.” Greener wrote that there were two Douglasses, “the one velvety, deprecatory, apologetic – the other insinuating, suggestive damning with shrug, a raised eyebrow, or a look of caution.”[9]

From 1885 to 1892, Greener served as secretary of the Grant Monument Association, where he is credited with having led the initial fundraising effort that eventually brought in donations from 90,000 people worldwide to construct Grant's Tomb.[10] From 1885 to 1890 he was chief examiner of the civil service board for New York City and County. In the 1896 election, he served as the head of the Colored Bureau of the Republican Party in Chicago.[11]

Just as Greener opposed Douglass, he was on the Washington side of the growing split in the African American world. On the one side was accomodationist, and therefore politically powerful and adequately funded, Booker T. Washington. On the other were Monroe Trotter, W. E. B. DuBois, and their followers, who insisted that under the Constitution they had rights and that those rights should be respected. From it were born the Niagara Conferences, and from them the NAACP. Greener was so closely allied with Washington that Washington sent him to the with the explicit charge of spying and reporting.

Diplomat[]

In 1898, Greener was appointed by President William McKinley as General Consul at Bombay, India. Soon he accepted a post as United States Commercial Agent in Vladivostok, Russia.[1] He successfully served as an American representative during the Russo-Japanese War but left the diplomatic service in 1905.[7]

Personal life[]

On September 24, 1874, Greener married Genevieve Ida Fleet, and they had six children.

Greener separated from his wife upon his posting to Vladivostok and took a Japanese common-law wife, Mishi Kawashima, with whom he had three children.

Though they never divorced, Fleet and her daughters changed their name to "Greene" to disassociate themselves from him.[citation needed] One of his daughters, Belle da Costa Greene, became personal librarian to J. P. Morgan and passed for white.[citation needed]

Later life and death[]

Greener settled in Chicago with relatives. He held a job as an agent for an insurance company, practiced law, and occasionally lectured on his life and times. He died of natural causes in Chicago on May 2, 1922, aged 78.[7]

His Harvard diploma and other personal papers were rediscovered in an attic in the South Side of Chicago in the early 21st century.[2] A great deal of discussion surrounds where the papers should be archived.

Legacy[]

Along with having accomplished many African-American firsts, Greener earned several awards in his lifetime.

In 1902, the Chinese government decorated him with the Order of the Double Dragon for his service to the Boxer War and assistance to Shansi famine sufferers.[1]

He received two honorary Doctorates of Laws, from Monrovia College in Liberia in 1882 and Howard University in 1907.[1] Phillips Academy and University of South Carolina both grant annual scholarships in Greener's name.[13]

The central quadrangle at Phillips Academy was named in honor of Greener in 2018. The University of South Carolina erected a statue of Greener.[14]

In 2009, some of his personal papers were discovered in the attic of an abandoned home on the south side of Chicago by a member of a demolition crew.[2][5]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Hatley, Leshell (2010-08-26). "Richard T. Greener: 1st Black Graduate of Harvard University". The Black Scholars Index. Archived from the original on 2010-12-27. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Janssen, Kim (2012-03-11). "'It gives me gooseflesh': Remarkable find in South Side attic". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on 2012-03-13.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A legal and political advisor, Richard Greener". African American Registry. Retrieved 2012-03-17.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising, GM Rewell & Company, 1887, pp. 327–335.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schafer, Susan A. (2013-10-15). "Black Scholar's Post-Civil War Diploma Survives". Associated Press. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ^ "Richard T. Greener". University of South Carolina. 2013-11-23. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Mounter, Michael Robert. "A Brief Biography of Richard Greener". University of South Carolina. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

- ^ Blight (2018), pp. 637.

- ^ Blight (2018), pp. 640-643.

- ^ National Park Service, U.S. Dept. of Interior (2012). General Grant (372-849/90989 ed.). Washington, DC: GPO.

- ^ "Greener, Richard Theodore". South Carolina Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2019-02-05.

- ^ Image from The Colored American in 1900; older version is in Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner, Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising, G. M. Rewell & Company, 1887, pp. 327-335.

- ^ "Richard T. Greener Endowment Fund". My Carolina Alumni Association. Retrieved 2012-03-16.

- ^ Wilks, Avery (January 29, 2017). "Statue to Honor 1st Black Professor". The State. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

Further reading[]

- Altman, Susan; Joel Kemelhor (2001) [1997]. Encyclopedia of African-American heritage (2nd ed.). New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 9780816041268. OCLC 49376561. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Chaddock, Katherine Reynolds (2017). Uncompromising activist : Richard Greener, first black graduate of Harvard College. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9781421423296. OCLC 983568517.

- Blight, David W. (2018). Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781416590323.

- Corley, Cheryl (April 23, 2012). "Discovery Sparks Interest In Forgotten Black Scholar". All Things Considered. Washington, DC: NPR. Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- Miles, Johnnie H.; J. J. Davis; S. E. Ferguson-Roberts; R. G. Giles (2001). Almanac of African American Heritage: a book of lists featuring people, places, times, and events that shaped Black culture. Paramus, NJ, USA: Prentice Hall Press. ISBN 9780735202269. OCLC 651947581.

- Robert Mounter, Michael (2002). Richard Theodore Greener : the idealist, statesman, scholar and South Carolinian (Ph. D. Thesis/dissertation). Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina. OCLC 52198252, 773942702.

- Potter, Joan (November 24, 2009) [1994]. African American Firsts (Revised ed.). New York, NY: Dafina Imprint, Kessington Publishing Corp. ISBN 9780758241665. OCLC 535901432. Retrieved April 23, 2012. (subscription required) for electronic book.

External links[]

- 1844 births

- 1922 deaths

- African-American lawyers

- American diplomats

- Harvard College alumni

- Howard University faculty

- Oberlin College alumni

- Phillips Academy alumni

- American librarians

- African-American librarians

- South Carolina Republicans

- New York (state) Republicans

- Illinois Republicans