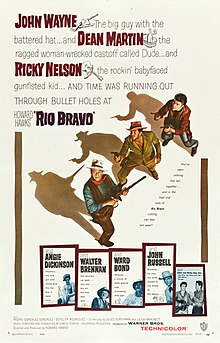

Rio Bravo (film)

| Rio Bravo | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Howard Hawks |

| Screenplay by | |

| Based on | "Rio Bravo" by B. H. McCampbell |

| Produced by | Howard Hawks |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Russell Harlan |

| Edited by | Folmar Blangsted |

| Music by | Dimitri Tiomkin |

Production company | Armada Productions [1] |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 141 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $1,214,899[3] |

| Box office | $5.75 million (US and Canada rentals)[4] |

Rio Bravo is a 1959 American Western film produced and directed by Howard Hawks and starring John Wayne, Dean Martin, Ricky Nelson, Angie Dickinson, Walter Brennan, and Ward Bond. Written by Jules Furthman and Leigh Brackett, based on the short story "Rio Bravo" by B. H. McCampbell, the film stars Wayne as a Texan sheriff who arrests the brother of a powerful local rancher for murder and then has to hold the man in jail until a U.S. Marshal can arrive. With the help of a "cripple", a drunk and a young gunfighter, they hold off the rancher's gang. Rio Bravo was filmed on location at Old Tucson Studios outside Tucson, Arizona, in Technicolor.

In 2014, Rio Bravo was deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry.[5][6]

Plot[]

Joe Burdette, the spoiled younger brother of wealthy land baron Nathan Burdette, taunts town drunk Dude by tossing money into a spittoon. The sheriff, John T. Chance, stops Dude from reaching into the spittoon, prompting Dude to lash out and knock Chance unconscious. Joe starts to beat Dude for fun, shooting and killing an unarmed bystander who attempts to stop him. Chance recovers, follows Joe into Nathan's personal saloon, and, with help from a penitent Dude, overcomes Nathan's men and arrests Joe for murder.

Chance's friend Pat Wheeler attempts to enter town with a wagon train of supplies and dynamite, but has to force his way through Nathan Burdette's men. Chance reveals that he, Dude (who used to be a deputy before he became a drunk), and his old crippled deputy Stumpy are all that stand between Nathan's small army and Joe, whom they wish to free. Chance notices young gunslinger Colorado Ryan in Wheeler's wagon train, but Colorado promises he doesn't want to start any trouble.

That night, Carlos Robante, the owner of the local hotel, warns Chance that Wheeler is trying to recruit fighters. Chance tries to stop Wheeler, not wanting anyone to get hurt on his account. Wheeler asks if Colorado could help, but Colorado politely declines, feeling that it's not his fight. Chance then notices a rigged card game at the hotel. Recognizing one of the players as a wanted woman, "Feathers", the widow of a cheating gambler, he confronts her. However, Colorado reveals that another player is the cheater.

Out in the street, Wheeler is gunned down. Chance and Dude pursue the killer into Nathan's saloon, and Chance allows Dude to prove himself and confront the killer, earning the respect of Nathan's men. Colorado and the rest of Wheeler's men are forced to stay in town to await a court order releasing Wheeler's possessions, and the wagons are left behind the Burdette warehouse. After Feathers secretly stays up all night with a shotgun to guard Chance, an irritated Chance orders Feathers to leave town for her safety. She refuses, and the two begin to bond.

Nathan himself rides into town. Stumpy, having old grudges with the Burdettes, threatens to shoot Joe if any trouble starts around the jail. In response, Nathan has his saloon musicians repeatedly play "El Degüello", a.k.a. "The Cutthroat Song". Colorado realizes the song means Nathan will show no mercy, and warns Chance.

Chance gives Dude back some clothes and guns he left behind when he became a drunkard, and Dude gets a haircut and shave, trying to start afresh. Unfortunately, Stumpy doesn't recognize Dude when he returns, and shoots at him, shattering Dude's nerves. The next day, Dude is still shaky and finds himself ambushed by Burdette's men, who threaten to kill him unless Chance lets Joe go. Colorado and Feathers distract the men long enough for Chance to get his rifle, and he and Colorado shoot down the men and free Dude. Dude thinks about quitting and letting Colorado take his place, but when he hears "El Degüello" being played, he resolves to see the thing through to the end.

Dude and Chance return to the hotel so Dude can take a bath, but Burdette's men capture Carlos' wife Consuelo and use her to lure Chance into a trap. Dude tells Chance to take the men to the jail, under pretext that Stumpy would let Joe out. However, Stumpy opens fire, as Dude secretly predicted. In the chaos, some men drag Dude off to Nathan, who demands a trade—Dude for Joe. Chance agrees, but brings Colorado as backup. Dude and Joe brawl during the trade, and a firefight ensues. Stumpy throws some sticks of dynamite from the wagons into the warehouse where Burdette and his men are holed up, and Chance detonates them with his rifle, abruptly ending the fight.

With both Burdettes and their few surviving gunmen in jail, Chance is able to finally spend some time with Feathers and admit his feelings for her. Colorado volunteers to guard the jail, allowing Stumpy and Dude to enjoy a night-out in the town.

Cast[]

- John Wayne as John T. Chance

- Dean Martin as Dude

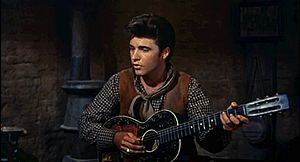

- Ricky Nelson as Colorado/Ryan

- Angie Dickinson as Feathers

- Walter Brennan as Stumpy

- Ward Bond as Pat Wheeler

- John Russell as Nathan Burdette

- Pedro Gonzalez Gonzalez as Carlos Robante

- Estelita Rodriguez as Consuelo Robante

- Claude Akins as Joe Burdette

Malcolm Atterbury and Harry Carey Jr. also receive screen credits in the film's opening, but their scenes were deleted from the final film.[7]

Production[]

Exteriors for the film were shot at Old Tucson Studios, just outside Tucson.[8] Filming took place in the summer of 1958, and the movie's credits gave 1958 for the copyright; the film was released in March 1959.

Rio Bravo is generally regarded as one of Hawks' best, and is known for its long opening scene which contains no dialogue. The film received favorable reviews, and was successful, taking in over US$5.5 million.[citation needed]

A brief clip from Rio Bravo was among the archive footage later incorporated into the opening sequence of Wayne's last film, The Shootist, to illustrate the backstory of Wayne's character.

As was often the case in a John Wayne Western, Wayne wore his "Red River D" belt buckle in the movie.[9] It can be clearly seen in the scene where Nathan Burdette comes to visit his brother Joe in the jail where he is being held for the U.S. Marshal about 60 minutes into the film.

The story was credited to "B.H. McCampbell." According to Todd McCarthy's 1997 biography, "Howard Hawks: The Grey Fox of Hollywood," this was actually Hawks' eldest daughter, Barbara Hawks McCampbell (McCampbell being her married name). Her contribution was the idea of using dynamite in the final shootout. [10]

Soundtrack[]

The musical score was composed by Dimitri Tiomkin. His score includes the hauntingly ominous "El Degüello" theme, which is heard several times.[11] The Colorado character identifies the tune as "The Cutthroat Song". He relates that the song was played on the orders of General Antonio López de Santa Anna to the Texans holed up in the Alamo, to signify that no quarter would be given to them. The tune was used in Wayne's film The Alamo (1960). Composer Ennio Morricone recalled that director Sergio Leone asked him to write "Dimitri Tiomkin music" for A Fistful of Dollars. The trumpet theme is similar to Tiomkin's "Degüello" (the Italian title of Rio Bravo was Un dollaro d'onore, A Dollar of Honor).[citation needed]

Because the film starred a crooner, Martin, and a teen idol, Nelson, Hawks included three songs in the soundtrack. Before the big showdown, in the jail house, Martin sings "My Rifle, My Pony, and Me" (which contains new lyrics to a Tiomkin tune that appeared in Red River), accompanied by Nelson, after which Nelson sings a brief version of "Get Along Home, Cindy", accompanied by Martin and Brennan. Over the closing credits, Martin, backed by the Nelson Riddle Orchestra, sings a specially composed song, "Rio Bravo", written by Tiomkin with lyrics by Paul Francis Webster. Nelson later paid homage to both the film and his character, Colorado, by including the song "Restless Kid" on his 1959 LP, Ricky Sings Again.

Members of the Western Writers of America chose "My Rifle, My Pony, and Me" as one of the Top 100 Western songs of all time.[12]

High Noon debate[]

The film was made as a response to High Noon,[13] which is sometimes thought to be an allegory for blacklisting in Hollywood, as well as a critique of McCarthyism.[14] Wayne would later call High Noon "un-American" and say he did not regret helping run the writer, Carl Foreman, out of the country.[15] Director Howard Hawks went on the record to criticize High Noon by saying, "I didn't think a good sheriff was going to go running around town like a chicken with his head cut off asking for help, and finally his Quaker wife had to save him."[16] According to film historian Emanuel Levy, Wayne and Hawks teamed up deliberately to rebut High Noon by telling a somewhat similar story their own way: portraying a hero who does not show fear or inner conflict and who never repudiates his commitment to public duty, while only allying himself with capable people, despite offers of help from many other characters.[17] In Rio Bravo, Chance is surrounded by allies—a deputy who is brave and good with a gun, despite recovering from alcoholism (Dude), a young untried but self-assured gunfighter (Colorado), a limping "crippled" old man who is doggedly loyal (Stumpy), a Mexican innkeeper (Carlos), his wife (Consuelo), and an attractive young woman (Feathers)—and repeatedly turns down aid from anyone he does not think is capable of helping him,[16] though in the final shootout they come to help him anyway. "Who'll turn up next?" Wayne asks amid the gunfire, to which Colorado replies: "Maybe the girl with another flower pot."

Reception[]

In the United Kingdom, Rio Bravo was not originally even reviewed for Sight & Sound;[18] Leslie Halliwell gave the film two out of four stars in his Film Guide, describing it as a "cheerfully overlong and slow-moving Western" that was nevertheless "very watchable for those with time to spare".[19] The film was taken more seriously by British critics such as Robin Wood, who rated it as his top film of all time and wrote a book on it in 2003 for the British Film Institute, publishers of Sight & Sound. Pauline Kael called the film "silly, but with zest; there are some fine action sequences, and the performers seem to be enjoying their roles."[20]

Rio Bravo has a 100% Rotten Tomatoes rating[21] and was the second highest-ranking Western (63rd overall) in the 2012 Sight & Sound critics' poll of the greatest films ever made.[22]

In 2008, the American Film Institute nominated this film for its Top 10 Western Films list.[23]

Remakes and inspirations[]

This section does not cite any sources. (July 2021) |

Remakes[]

This section possibly contains original research. (July 2021) |

Howard Hawks went on to make two loose variations of Rio Bravo, on both occasions under a different title. Both of these remakes were directed by Hawks, both starred John Wayne, and in each case, the script was written by Leigh Brackett. All involve lawmen working against an entrenched criminal element, partially by "holing up" in their jailhouses.

- The first remake, El Dorado, was filmed in 1966, but it was not released in the United States (by Paramount) until the summer of 1967. In this film, Robert Mitchum played the Dean Martin role, Arthur Hunnicutt the Walter Brennan character, and James Caan the Ricky Nelson role. Hawks again named the Nelson/Caan character after a state (in this case, Mississippi) and in a wry, humorous twist on the original film, Hawks made him inept with firearms, but skilled with a knife.

- The second remake, Rio Lobo, was made in 1970 with a plot much further off the original mold, starting with the absence of a lawman-turned-drunkard character. This began with a Confederate train robbery of a Union gold shipment during the American Civil War, then moved to a postwar Texas county thoroughly controlled by a rich, arrogant rancher. The heroes, with the exception of an old man similar to Brennan and Hunnicutt's characters in the previous pictures (Jack Elam here), were complete outsiders. Along with Wayne and Elam, this movie starred Mexican film star Jorge Rivero (as Frenchie), Christopher Mitchum (Robert Mitchum's son), and Jennifer O'Neill.

Inspirations[]

- Feathers' dialogue was occasionally inspired by the character of "Slim" (Lauren Bacall) in the 1944 To Have and Have Not, as when, after the first kiss, she says: "It's better when two people do it," recalling the phrase "It's even better when you help;" and again later when she says, "I'm hard to get—you're going to have to say you want me," recalling Slim's "I'm hard to get, Steve—all you have to do is ask me."

- (The Man with the Silver Star), a 1969 album from the French comics series Blueberry, was directly inspired by Rio Bravo. The plot is virtually the same. Blueberry plays the role of sheriff John T. Chance; McClure, a whiskey-adoring old man, combines the roles of Dude and Stumpy; Dusty plays the role of Colorado; Miss March, the teacher, plays the role of a less morally challenged Feathers; and instead of the Burdettes, it has the Bass brothers.

- John Carpenter's 1976 film Assault on Precinct 13, though not a remake of Rio Bravo, was inspired by the film. Carpenter borrowed some elements from the earlier film's plot, but set it in 1970s Los Angeles. He also paid homage to the original film by using the pseudonym "John T. Chance", the name of Wayne's character, for his editing credit. This film was also remade in 2005 by Jean-Francois Richet, moving the film's setting to Detroit.

- Ghosts of Mars, a 2001 film also by Carpenter, retains many of the elements that were developed in Rio Bravo and Assault on Precinct 13, but takes place in a science-fiction setting.

- The Nest, a 2002 film by Florent Emilio Siri, starring Samy Naceri, Benoît Magimel, Nadia Farès, Pascal Greggory, and Sami Bouajila, is a quasi-remake of Assault on Precinct 13.

Music[]

- "My Rifle, My Pony and Me"—sung by Dean Martin and Ricky Nelson

- "Cindy"—sung by Ricky Nelson, Dean Martin and Walter Brennan

- "Rio Bravo"—sung by Dean Martin (end credits)

Comic book adaption[]

- Dell Four Color #1018 (June 1959)[24][25]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Stafford, Jeff (2020-10-05). "Rio Bravo overview". Turner Classic Movies. Archived from the original on 2020-10-21. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- ^ "Catalog listing for Rio Bravo". AFI. 1959-04-04. Archived from the original on 2020-11-25. Retrieved 2020-10-05.

- ^ Flynn, Charles; McCarthy, Todd (1975). "The Economic Imperative: Why Was the B Movie Necessay?". In Flynn, Charles; McCarthy, Todd (eds.). Kings of the Bs : working within the Hollywood system : an anthology of film history and criticism. E. P. Dutton. p. 29.

- ^ Cohn, Lawrence (October 15, 1990). "All-Time Film Rental Champs". Variety. Penske Business Media, LLC.: M182.

- ^ "Cinematic Treasures Named to National Film Registry". National Film Preservation Board. Library of Congress. 17 December 2014. ISSN 0731-3527. Archived from the original on 11 September 2018. Retrieved 4 August 2018.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on 2016-10-31. Retrieved 2020-05-08.

- ^ Hawks, Howard (2006). Breivold, Scott (ed.). Howard Hawks: Interviews. Univ. Press of Mississippi. p. 38. ISBN 9781578068333.

- ^ Commemoration: Howard Hawks' Rio Bravo, Warner Bros. DVD supplement.

- ^ "History of the Red River D Buckle". Red River D Belt Buckle. Archived from the original on 2021-01-23. Retrieved 2021-04-23.

- ^ suomy. "Rio Bravo Trivia Questions, Page 2, Movies Q-T". Funtrivia, Inc.

- ^ The Handbook of Texas Online Archived 2016-03-10 at the Wayback Machine, Texas State Historical Association (retrieved on November 22, 2006).

- ^ Western Writers of America (2010). "The Top 100 Western Songs". American Cowboy. Archived from the original on 13 August 2014.

- ^ Munn, Michael (2005). John Wayne: The Man Behind the Myth. New York: Penguin. p. 190. ISBN 0451214145. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Blacklist Archived 2009-02-07 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Manfred Weidhorn. "High Noon Archived 2012-07-23 at archive.today." Bright Lights Film Journal. February 2005. Accessed 12 February 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stafford, Jeff. "Rio Bravo". TCM Film Article. Turner Entertainment Network. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ Levy, Emanuel. "High Noon: Why John Wayne Hated the Film". Cinema 24/7. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ^ The Movie article by Phil Hardy, 1980

- ^ Halliwell, Leslie (1979). Halliwell's Film Guide to 8,000 English Language Films, Hart-Davis, MacGibbon, Granada.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2018-09-07. Retrieved 2019-03-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2020-11-24. Retrieved 2020-12-31.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Critics' top 100". British Film Institute. 2012. Archived from the original on February 7, 2016. Retrieved December 12, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10 Nominees" (PDF). Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2016-08-19.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- ^ "Dell Four Color #1018". Grand Comics Database.

- ^ Dell Four Color #1018 at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)

Further reading[]

- Byman, Jeremy (2004). Showdown at High Noon. Metuchen: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 0-8108-4998-4.

- McCarthy, Todd (2000). Howard Hawks. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3740-7.

- Roberts, Randy (1997). John Wayne. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-8970-7.

- Wood, Robin (2006). Howard Hawks. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3276-5.

- Wood, Robin (2003). Rio Bravo. London: BFI Pub. ISBN 0-85170-966-4.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Rio Bravo. |

- Rio Bravo essay [1] by Michael Schlesinger at National Film Registry

- Rio Bravo at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Rio Bravo at IMDb

- Rio Bravo at AllMovie

- Rio Bravo at the TCM Movie Database

- Rio Bravo at Rotten Tomatoes

- 1959 films

- 1959 Western (genre) films

- American Western (genre) films

- American buddy films

- English-language films

- Films scored by Dimitri Tiomkin

- Films about alcoholism

- Films directed by Howard Hawks

- Films set in Texas

- Films shot in Arizona

- Films shot in California

- Films with screenplays by Leigh Brackett

- Warner Bros. films

- United States National Film Registry films

- Films with screenplays by Jules Furthman

- American films

- Siege films

- Films adapted into comics