Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves

| Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves | |

|---|---|

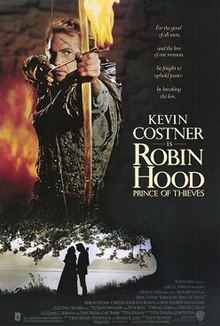

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Kevin Reynolds |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Story by | Pen Densham |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Douglas Milsome |

| Edited by | Peter Boyle |

| Music by | Michael Kamen |

Production company | Morgan Creek Productions[1] |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 143 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $48 million[3] |

| Box office | $390.5 million[4] |

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves is a 1991 American action adventure film based on the English folk tale of Robin Hood that originated in the 12th century. It was directed by Kevin Reynolds and stars Kevin Costner as Robin Hood, Morgan Freeman as Azeem, Christian Slater as Will Scarlett, Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Marian, and Alan Rickman as the Sheriff of Nottingham. The screenplay was written by Pen Densham and John Watson.

The film received mixed reviews from critics, who praised Freeman's and Rickman's performances and the music, but criticized Costner's performance, the screenplay and the overall execution. Nevertheless, it was a box office success, grossing more than $390 million worldwide, making it the second-highest-grossing film of 1991. Rickman received the BAFTA Award for Best Actor in a Supporting Role for his performance as George, Sheriff of Nottingham. The film's theme song "(Everything I Do) I Do It for You" by Bryan Adams was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Original Song, and it won the Grammy Award for Best Song Written for Visual Media.[5] Costner's performance as Robin Hood received poor reviews and won him the Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Actor.

Plot[]

1194, at the end of the Third Crusade. Richard the Lionheart, King of England is in France, leaving the cruel Sheriff of Nottingham—aided by his cousin Guy of Gisbourne; his foster mother, the witch Mortianna, and the corrupt Bishop of Hereford—to rule the land. Robin of Locksley, a young nobleman who followed the king, has been imprisoned in Jerusalem for five years. At Locksley Castle, Robin's father, who is loyal to King Richard, is killed by the Sheriff's men after refusing to join them.

Robin and his comrade, Peter Dubois, break out of prison, saving the life of a Moor named Azeem. Mortally wounded, Peter makes Robin swear to protect his sister, Marian, and distracts the pursuers so Robin can escape. Robin returns to England with Azeem, who has vowed to accompany him until his life-debt is repaid. After a run-in with Gisbourne, Robin goes home and finds his father's rotted corpse suspended in the ruined castle. Duncan, an old family retainer blinded by Gisbourne, tells him how his father was falsely accused of worshipping Satan. Meanwhile, the Sheriff consults Mortianna, who foresees Richard's return and, panicking, cries that Robin and Azeem "will be our deaths."

Robin tells Marian of Peter's death and his promise, but Marian sees little need for his protection and is determined to stay and look after the people on her demesne. After fleeing the Sheriff's forces, Robin, Azeem and Duncan encounter a band of outlaws hiding in Sherwood Forest, led by Little John. Among them is Will Scarlet, who holds a grudge against Robin. Robin assumes command, shaping them into a formidable force in opposition to Nottingham. The outlaws rob rich folk passing through the forest and distribute the stolen wealth and food among the poor. Friar Tuck joins them once he understands their cause. Marian offers Robin any aid she can, and they begin to fall in love.

Robin's successes infuriate the Sheriff, who steps up his mistreatment of the people, increasing their support for Robin. The Sheriff kills Gisbourne for failing to deal with the outlaws and hires vicious Celtic warriors to bolster his forces. The Bishop betrays Marian after she gives him a message warning King Richard of Nottingham's plots, and she is taken prisoner. Duncan rides to Sherwood, but is followed. The Sheriff burns the outlaws' hideout and captures many; Robin is presumed dead. To consolidate his power and claim the throne, the Sheriff proposes to Marian (who is Richard's cousin), claiming that if she accepts, he will spare the lives of the woodsmen and their families. Marian reluctantly agrees, but the ringleaders are to be hung anyway as part of the wedding celebration.

Will, one of the captured, makes a deal with the Sheriff: If Robin is alive, he will find him and kill him. Will does find Robin, Azeem, John and a handful of other survivors and informs them of the Sheriff's plans, but does not trust Robin. When Robin asks why Will hates him so, Will reveals that he is Robin's half-brother. After Robin's mother died, his father took comfort with a peasant woman. Young Robin's anger over what he saw as a betrayal of his mother's memory caused his father to leave Will's mother, leaving Will fatherless. Robin is overjoyed to learn that he has a brother, and they reconcile.

On the wedding day, Robin and his men infiltrate Nottingham Castle and free the prisoners. Azeem inspires the Nottingham peasants to revolt, forcing the Sheriff to retreat with Marian into his keep. The Bishop performs the marriage, and the Sheriff is about to consummate it when Robin bursts in and kills the Sheriff after a fierce fight. Mortianna is slain by Azeem, fulfilling his life-debt to Robin. Tuck finds the Bishop fleeing with bags of gold, and burdens him with additional treasure before defenestrating him.

Robin and Marian profess their love for each other. Their marriage in Sherwood is interrupted by the return of King Richard, who gives the bride away and thanks Robin for saving his throne.

Cast[]

- Kevin Costner as Robin of Locksley[6]

- Morgan Freeman as Azeem Edin Bashir Al Bakir

- Mary Elizabeth Mastrantonio as Lady Marian

- Christian Slater as Will Scarlett

- Alan Rickman as Sheriff of Nottingham[7]

- Geraldine McEwan as Mortianna

- Michael McShane as Friar Tuck

- Brian Blessed as Lord Locksley

- Michael Wincott as Guy of Gisborne

- Nick Brimble as Little John

- Harold Innocent as the Bishop of Hereford

- Walter Sparrow as Duncan

- Daniel Newman as Wulf

- Daniel Peacock as Bull

- Jack Wild as Much

- Soo Drouet as Fanny

- Liam Halligan as Peter Dubois

- Michael Goldie as Kenneth

- Sean Connery as King Richard[8] (uncredited)

Production[]

Development[]

In August 1989, British writer-producer Pen Densham broke with the traditional account of Robin Hood as a devil-may-care adventurer (best embodied by Errol Flynn in 1938) by reimagining him as a rich kid transformed into a socially conscious rebel by imprisonment in Jerusalem during the Crusades. He wrote a 92-page outline, which was then rewritten as a screenplay by his producing partner, John Watson. On February 14, 1990, Morgan Creek, the small production company of Young Guns (1988) and Major League (1989), saw "gold on the page" and immediately funded the film. Watson scouted filming locations in the United Kingdom, setting September 3 as the filming deadline in aggressive competition against other potential Robin Hood remakes from Twentieth Century Fox (Morgan Creek's former distribution partner) and Tri-Star Pictures.[9]

Kevin Reynolds had directed Kevin Costner extensively in the past, including the challenging buffalo hunt scene of Dances with Wolves. Reynolds said: "I'd done two pictures that hadn't made a dime, so I kind of knew [the studio] wanted me [for Robin Hood] because of my connections with Kevin." Indeed, Costner had already rejected the script until hearing that Reynolds was directing: "I felt Kevin was such a good filmmaker I would do it".[9]

Reynolds said, "what I did not want to do was Indiana Jones. That has been done already". Costner wanted an accent but Reynolds thought it would distract audiences, and their indecision resulted in a drastically uneven delivery between each scene. EW reported, "Even before it was finished, Costner was the subject of embarrassing rumors that his performance was too laid-back and his accent more LA than UK."[9]

Filming[]

Costner's explosive career gave him only a few days between the long-term epic projects of Dances with Wolves, Robin Hood, and JFK. This project's timeframe was compressed by the winter in England and by competition with other possible Robin Hood films, giving Reynolds only 10 weeks for preproduction and little time for planning, rehearsal, or revision. Costner said, "It's very dangerous to be [working] so fast. We are relying on the weather, and every time the weather turns against us we could get behind. When that happens there is always the feeling that certain people want to do something about it to shorten the filming time. That is not always the cure." Reynolds said, "Are things going as planned? Ha! You always start with a picture in your mind, and it is a compromise all the way from there. We have been struggling from Day One. We are trying to finish by Christmas, and the days are getting shorter. It's horrible." The suddenly changing weather caused jet traffic to be diverted overhead on the first day of filming in the Burnham Beeches location, ten miles from London's Heathrow Airport.[9]

Principal exteriors were shot on location in the United Kingdom. A second unit filmed the medieval walls and towers of the Cité de Carcassonne in the town of Carcassonne in Aude, France, for the portrayal of Nottingham and its castle. Locksley Castle was Wardour Castle in Wiltshire—restored in an early shot using a matte painting. Marian's manor was filmed at Hulne Priory in Northumberland. Scenes set in Sherwood Forest were filmed at various locations in England: Theoutlaws' encampment was filmed at Burnham Beeches in Buckinghamshire, south of the real Sherwood Forest in Nottinghamshire;[9] the fight scene between Robin and Little John was at Aysgarth Falls in North Yorkshire; and Marian sees Robin bathing at Hardraw Force, also in North Yorkshire.[10] Sycamore Gap on Hadrian's Wall in Northumberland was used for the scene when Robin first confronts the sheriff's men.[11] Chalk cliffs at Seven Sisters, Sussex were used as the locale for Robin's return to England from the Crusades.[12]

Interior scenes were completed at Shepperton Studios in Surrey.[10]

Post-production[]

Furious at the studio's repeated demands for yet another heavy editing session just to boost Costner's presence and prevent Rickman's performance from stealing the movie—and at the studio locking his own editor out of the cutting room—Reynolds walked out of the project weeks before theatrical debut. He did not attend the screening.[9]

Extended cut[]

A 155-minute extended cut of the film was released on home media in 2009. The extended cut shows in detail the conspirators' plot to steal the throne from King Richard, as well as further exploring the relationship between the Sheriff and Mortianna. In one scene, Mortianna explains that she killed the true George Nottingham as a baby and replaced him with her own infant son, revealing that she is in fact the Sheriff's real mother. Also included are scenes which show Mortianna instructing Nottingham to remove the tongue of John Tordoff's scribe character, forcing him to communicate via chalk-board in subsequent scenes. Nottingham, however, only pretends he removed the Scribe's tongue as the Scribe later provides spoken directions to Robin and Azeem when they pursue the kidnapped Marian.[13]

Music[]

| Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (Original Soundtrack) | |

|---|---|

| Soundtrack album by Michael Kamen | |

| Released | July 2, 1991 |

| Length | 60:22 (original), 134:39 (2017 expansion), 220:46 (2020 expansion) |

| Label | Morgan Creek Productions (original), Intrada Records (expansions) |

The original music score was composed, orchestrated and conducted by Michael Kamen. An excerpt from the main title music was subsequently used as the logo music for Morgan Creek,[14] and has been used by Walt Disney Studios Home Entertainment in intros for trailers on DVD/Blu-ray.[15] In 2017, the specialty film music label Intrada Records released a two-disc CD album containing the complete score and alternates, though not the songs from Bryan Adams and Jeff Lynne.[16] In 2020, Intrada issued a four-disc album; with the film score on the first 2 CDs; CD 3 having alternate takes and additional music, including the Morgan Creek Productions fanfare which was derived from this score; CD 4 features the assemblies used on the 1991 soundtrack album. The songs are again absent.[17]

| No. | Title | Length |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Overture" / "A Prisoner of the Crusades" | 8:27 |

| 2. | "Sir Guy of Gisborne" / "The Escape to Sherwood" | 7:27 |

| 3. | "Little John" / "The Band in the Forest" | 4:52 |

| 4. | "The Sheriff and His Witch" | 6:03 |

| 5. | "Maid Marian" | 2:57 |

| 6. | "Training" / "Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves" | 5:15 |

| 7. | "Marian at the Waterfall" | 5:34 |

| 8. | "The Abduction" / "The Final Battle at the Gallows" | 9:53 |

| 9. | "(Everything I Do) I Do It for You" (sung by Bryan Adams) | 6:33 |

| 10. | "Wild Times" (sung by Jeff Lynne) | 3:12 |

Release[]

Classification[]

Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves was submitted for classification from the British Board of Film Classification, which required fourteen seconds to be cut from the film to obtain a PG rating.[2]

Home media[]

The original theatrical cut of the film was released on VHS in the US on May 13, 1992,[18] and on DVD on September 30, 1997.[19] A 2-disc special-edition DVD was released in the US on June 10, 2003,[20] containing a 155-minute-long extended version of the film. This alternate cut of the film was released on Blu-ray in the US on May 26, 2009.[21]

Reception[]

Box office[]

The film grossed $25 million in its opening weekend and $18.3 million in its second. The film eventually made $390,493,908 at the global box office, making it the second-highest-grossing film of 1991, immediately behind Terminator 2: Judgment Day. It enjoyed the second-best opening for a nonsequel, at the time.[22][23][24][25]

Critical response[]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 52% based on 56 reviews, with an average rating of 5.70/10. The critical consensus reads, "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves brings a wonderfully villainous Alan Rickman to this oft-adapted tale, but he's robbed by big-budget bombast and a muddled screenplay."[26] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 51 out of 100, based on 25 critics, indicating "mixed or average reviews".[27] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A" on an A+ to F scale.[28]

Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert praised Freeman's performance as well as Rickman's, but ultimately decried the film as a whole, giving it two stars and stating, "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves is a murky, unfocused, violent, and depressing version of the classic story... The most depressing thing about the movie is that children will attend it expecting to have a good time."[29] The New York Times gave the film a negative review, with Vincent Canby writing that the movie is "a mess, a big, long, joyless reconstruction of the Robin Hood legend that comes out firmly for civil rights, feminism, religious freedom, and economic opportunity for all."[30] The Los Angeles Times also found the movie unsatisfactory.[31] Costner was criticized for not attempting an English accent,[32] and the film is mocked for Robin walking from the White Cliffs to Nottingham via Hadrian's Wall in an afternoon, a distance of 560 miles.[33]

Desson Thomson, writing for The Washington Post, gave a more positive review: "Fair damsels and noble sirs, you must free yourselves of these wearisome observations. This is a state-of-the-art retelling of a classic."[34] Owen Gleiberman, of Entertainment Weekly also gave a positive review: "As a piece of escapism, this deluxe, action-heavy, 2-hour-and-21-minute Robin Hood gets the job done."[35] Lanre Bakare, writing in The Guardian, calls Rickman's Sheriff, for which he won a BAFTA, a "genuinely great performance".[36]

Prince of Thieves was nominated for two Golden Raspberry Awards: Kevin Costner won the Worst Actor award for his performance as Robin Hood, while Christian Slater received a nomination for Worst Supporting Actor for his performances in this film and in Mobsters, but lost to Dan Aykroyd for Nothing but Trouble.[37]

In 2005, the American Film Institute nominated this film for AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores.[38]

Other media[]

Video games[]

Tie-in video games of the same name were released in 1991 for the Nintendo Entertainment System and Game Boy. Developed by Sculptured Software Inc. and Bits Studios, respectively, and published by Virgin Games, Inc., they were featured as the cover game for the July 1991 issue of Nintendo Power magazine.[39]

Toys[]

Kenner released a toy line consisting of action figures and playsets. All but one of the figures were derived by slight modifications to Kenner's well-known Super Powers line, while Friar Tuck, the vehicles and playseti were modified from Star Wars: Return of the Jedi toys.[40]

See also[]

- Princess of Thieves – 2001 television movie

- Robin Hood: Men in Tights – 1993 parody film

- Robin Hood – 1991 British film

- Robin Hood – English folk tale

References[]

- ^ Easton, Nina J. (July 24, 1990). "Costner May Put Morgan Creek Ahead of Robin Hood Pack". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "ROBIN HOOD - PRINCE OF THIEVES (PG) (CUT)". British Board of Film Classification. July 4, 1991. Retrieved January 19, 2016.

- ^ Billington, Michael (March 18, 1991). "Robin Hood Freshens Up A Film Legend". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ^ "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)". Box Office Mojo. October 17, 1991. Retrieved October 29, 2016.

- ^ "1992 Grammy Awards". metrolyrics.com. Archived from the original on February 9, 2009. Retrieved January 1, 2009.

- ^ Dowd, Maureen (June 9, 1991). "FILM; Hollywood's Superhunk Heads for Nottingham". The New York Times. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Leydon, Joe (June 9, 1991). "Robin Hood' and the uncertain science of hype". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Pugh, Tison (2009). "8: Sean Connery's Star Persona and the Queer Middle Ages". In Coyne Kelly, Kathleen; Pugh, Tison (eds.). Queer movie medievalisms. Farnham: Ashgate. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-7546-7592-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Pearce, Garth (June 21, 1991). "Behind-the-scenes trouble during "Robin Hood"". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved July 10, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pearce, Garth; Green, Simon (1991). Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. Bdd Promotional Book Co. pp. 22–34. ISBN 9780792456339.

- ^ Else, David & Sandra Bardwell, Belinda Dixon, Peter Dragicevich (2007). Lonely Planet: Walking in Britain. Lonely Planet. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-7410-4202-3.

- ^ Pirani, Adam (May 1991). "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves". Starlog. p. 40.

- ^ "Robin Hood: Prince Of Thieves, and the story of its extended cut". Film Stories. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ^ David Victor (August 30, 2012). "Studio Logo Music". Retrieved November 25, 2015.

- ^ "Film Score Monthly". July 10, 2009. Retrieved November 25, 2017.

- ^ "ROBIN HOOD: PRINCE OF THIEVES (2CD)". store.intrada.com.

- ^ "ROBIN HOOD: PRINCE OF THIEVES (4CD - REMASTERED AND EXPANDED)". store.intrada.com.

- ^ https://www.amazon.com/Robin-Hood-Prince-Thieves-VHS/dp/6302206294[bare URL]

- ^ "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves - Movie Review". www.commonsensemedia.org. July 20, 2005.

- ^ "Robin Hood - Prince of Thieves (Two-Disc Special Extended Edition)". DVD Talk.

- ^ https://www.amazon.com/Robin-Hood-Prince-of-Thieves-Blu-ray/dp/B001993Y3G[bare URL]

- ^ "Robin Hood prince of summer flicks with $18.3 million weekend". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Fox, David J. (June 25, 1991). "Robin Hood Still Riding Ahead of Box Office Pack". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ Fox, David J. (June 18, 1991). "'Robin' Hits Impressive Box Office Bull's-Eye". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ "Can 'Robin Hood' Keep Up Its Box-office Momentum?". Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved July 19, 2021.

- ^ "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ D'Alessandro, Anthony (November 22, 2018). "'Ralph' Breaking The B.O. With $18.5M Weds., Potential Record $95M Five-Day; 'Creed II' Pumping $11.6M Opening Day, $61M Five-Day". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ "Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves". Chicago Sun Times.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 14, 1991). "A Polite Robin Hood in a Legend Recast". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (June 14, 1991). "'Robin': Medieval Dash, New Age Muddle". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Easton, Nina J. (June 23, 1991). "A look inside Hollywood and the movies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 2, 2010.

- ^ https://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/jan/15/robin-hood-prince-of-thieves[bare URL]

- ^ Robin Hood, Prince of Thieves Reviews, Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, Entertainment Weekly, June 21, 1991

- ^ "My guilty pleasure – Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves". The Guardian. September 7, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, John (2005). The Official Razzie Movie Guide: Enjoying the Best of Hollywood's Worst. Grand Central Publishing. ISBN 0-446-69334-0.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years of Film Scores Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 7, 2016.

- ^ Tilden, Gail, ed. (July 1991). "Cover page". Nintendo Power. 26. ISSN 1041-9551.

- ^ Salvatore, Ron. "The recycling of the Force - Starwars". The Star Wars Collectors Archive. Retrieved February 6, 2016.

External links[]

![]() Quotations related to Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves at Wikiquote

- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves at IMDb

- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves at the TCM Movie Database

- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves at Box Office Mojo

- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves at Rotten Tomatoes

- "The Battle of Sherwood Forest", a 1991 Entertainment Weekly cover story about the film's tumultuous production.

- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves Transcript

- 1991 films

- English-language films

- 1990s action adventure films

- 1990s romantic drama films

- 1991 action films

- 1991 adventure films

- 1991 drama films

- American action adventure films

- American films

- American romantic drama films

- American vigilante films

- Crusades films

- Cultural depictions of Richard I of England

- Films about witchcraft

- Films directed by Kevin Reynolds

- Films scored by Michael Kamen

- Films set in Cumbria

- Films set in Jerusalem

- Films set in Kent

- Films shot at Shepperton Studios

- Films shot in Buckinghamshire

- Films shot in East Sussex

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in France

- Films shot in Hampshire

- Films shot in North Yorkshire

- Films shot in Northumberland

- Films shot in Wiltshire

- Morgan Creek Productions films

- Robin Hood films

- Warner Bros. films

- Warner Bros. Pictures franchises