Roman pharaoh

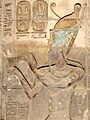

The Roman pharaohs,[1] rarely referred to as ancient Egypt's Thirty-fourth Dynasty,[2][a] is the term sometimes used for the Roman emperors in their capacity as rulers of Egypt, especially in Egyptology. After Egypt was incorporated into the Roman Empire in 30 BC, the people and especially the priesthood of the country continued to recognize the Roman emperors as pharaohs, according them traditional pharaonic titularies and depicting them with traditional pharaonic garb, engaging in traditional pharaonic activities, in artwork and at temples throughout Egypt.

Although the Egyptians themselves considered the Romans to be their pharaohs and the legitimate successors of the ancient pharaohs, the emperors themselves never adopted any pharaonic titles or traditions outside of Egypt, as these would have been hard to justify in the Roman world at large. Most emperors probably cared little of the status accorded to them by the Egyptians, with emperors rarely visiting the province more than once in their lifetime. Their role as god-kings was only ever officially acknowledged by the Egyptians themselves. This was a sharp contrast to the preceding dynasty of pharaohs of Hellenistic Ptolemaic Kingdom, who had spent the majority of their lives in Egypt, ruling from Alexandria. Pharaohs before Egypt's incorporation into the Achaemenid Empire in the Late Period had also all ruled the country from within Egypt. However, Roman Egypt was governed differently from other Roman provinces, with emperors hand-picking governors for the region and often treating it more like a personal possession than a province.

Though not all Roman emperors were recognized as pharaohs, Egyptian religion demanded the presence of a pharaoh to act as the intermediate between humanity and the gods. The Romans being seen as pharaohs proved to be the most simple solution, and was similar to how the Persians had been regarded as pharaohs centuries prior (constituting the Twenty-seventh and Thirty-first dynasties).

Though Egypt continued to be a part of the Roman Empire until it was conquered by the Rashidun Caliphate in 641 AD, the last Roman emperor to be conferred the title of pharaoh was Maximinus Daza (reigned 311–313 AD). By his time, the view of Romans as pharaohs had already been declining for some time due to Egypt being on the periphery of the Roman Empire (in contrast to the traditional pharaonic view of Egypt as the center of the world). The spread of Christianity throughout the empire in the 4th century, and the transformation of Egypt's capital Alexandria into a major Christian center, decisively ended the tradition, due to the new religion being incompatible with the traditional implications of being pharaoh.

History[]

Cleopatra VII had affairs with Roman dictator Julius Caesar and Roman general Mark Antony, but it was not until after her 30 BC suicide (after Mark Antony was defeated by Octavian, who would later be Emperor Augustus Caesar) that Egypt became a province of the Roman Republic. Subsequent Roman emperors were accorded the title of pharaoh, although exclusively while in Egypt. As such, not all Roman emperors were recognized as pharaohs. Although Octavian made a point of not taking the Pharaonic crown when he conquered Egypt, which would have been difficult to justify to the wider empire considering the vast amount of propaganda which he had spread about the "exotic" behavior of Cleopatra and Antony,[3] the native population of Egypt regarded him as the pharaoh succeeding Cleopatra and Caesarion. Depictions of Octavian, now called Augustus, in traditional pharaonic garbs (wearing different crowns and the traditional kilt) and sacrificing goods to various Egyptian gods were made as early as around 15 BC and they are present in the Temple of Dendur, built by Gaius Petronius, the Roman governor of Egypt.[4] Even earlier than that, Augustus had been accorded royal titles in the Egyptian version of a 29 BC stele made by Cornelius Gallus, despite royal titles not being present in the Latin or Greek-language versions of the same text.[5]

Unlike the preceding Ptolemaic pharaohs and pharaohs of other previous foreign dynasties, the Roman emperors were rarely physically present in Egypt. As such, the traditional role of the pharaoh, a living embodiment of the gods and cosmic order, was somewhat harder to justify; an emperor rarely visited the province more than once in their lifetime, a sharp contrast to previous pharaohs who had spent a majority of their lives in Egypt. Even then, Egypt was hugely important to the empire as it was highly fertile and the richest region of the Mediterranean. Egypt was governed differently from other provinces, emperors treating it more like a personal possession than a province; hand-picking governors and administering it without the Roman Senate's interference - no senator was ever named governor of Egypt and they were even barred from visiting the province without explicit permission.[6]

Vespasian was the first emperor since Augustus to appear in Egypt.[7] At Alexandria he was hailed as pharaoh; recalling the welcome of Alexander the Great at the Oracle of Zeus-Ammon of the Siwa Oasis, Vespasian was proclaimed the son of the creator-deity Amun (Zeus-Ammon), in the style of the ancient pharaohs, and an incarnation of Serapis in the manner of the Ptolemies.[8] As pharaonic precedent demanded, Vespasian demonstrated his divine election by the traditional methods of spitting on and trampling a blind and crippled man, thereby miraculously healing him.[9]

To the Egyptians, their religion demanded that there was a pharaoh to act as the intermediary between the gods and humanity. As such, the emperors continued to be regarded as pharaohs since this proved the most simple solution, disregarding the actual political situation, similar to how Egypt had regarded the Persians or Greeks before the Romans. The abstract nature of the role of these "Roman pharaohs" ensured that the priests of Egypt could demonstrate their loyalty both to their traditional ways and to the new foreign ruler. The Roman emperors themselves mostly ignored the status accorded to them by the Egyptians; in Latin and Greek their titles continued to be Roman only (Imperator in Latin and Autokrator in Greek) and their role as god-kings was only ever acknowledged domestically by the Egyptians themselves.[10]

As Christianity became more and more accepted within the empire, eventually becoming the state religion, emperors no longer found it possible to accept the traditional implications of being pharaoh (a position firmly rooted in the Egyptian religion) and by the early 4th century, Alexandria itself, the capital of Egypt since the time of Alexander the Great, had become a major center of Christianity. By this point, the view of the Romans as pharaohs had already declined somewhat; Egypt being on the periphery of the Roman Empire was much different from the traditional pharaonic view of Egypt as the center of the world. This was evident in the imperial pharaonic titulatures; though early emperors had been given elaborate titulatures similar to those of the Ptolemies and native pharaohs before them, emperors from Commodus (reigned 180–192 AD) onwards were usually given just a nomen, though still written within a cartouche (as all pharaonic names were).[11] Although there continued to be Roman emperors for centuries, until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD, and Egypt continued to be a part of the empire until 641 AD, the last Roman emperor to be conferred the title of pharaoh was Maximinus Daza (reigned 311–313 AD).[12]

Despite actual dynastic relationships (there were at least four distinct dynasties of Roman emperors between Augustus and Maximinus Daza), the period of Roman rule over Egypt in its entirety is sometimes referred to as the Thirty-fourth Dynasty.[2] Some nineteenth century Coptic scholars, such as Mikhail Sharubim and Rifa'a al-Tahtawi, split the Roman emperors into two dynasties, a Thirty-fourth Dynasty for pagan emperors and a Thirty-fifth Dynasty encompassing Christian emperors from Theodosius I to the Muslim conquest of Egypt in 641 AD, although no Christian Roman emperor was ever referred to as pharaoh by the population of ancient Egypt.[13]

Emperors recognised as pharaohs[]

| Depiction | Name & reign | Pharaonic titulary | Ref | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Horus name | Golden Horus | Prenomen | Autokrator | Nomen/Kaisaros | |||

|

Augustus r. 30 BC – AD 14 |

Hor-Tjemaawerpehty Hunubenermerut Heqaheqau Setepenptahnenuitnetjeru "The sturdy-armed one with great strength, the youth sweet of love, ruler of rulers, chosen of Ptah and Nun, the father of the gods" |

— | Heqaheqau Setepenptah "Ruler of rulers, chosen by Ptah" |

Autukratur Emperor |

Kyseres Caesar |

[14] |

|

Tiberius r. 14–37 |

Hor-Tjemaawerpehty Hununefer Benermerut Heqaheqau Setepenptah Nenuitnetjeru "The sturdy-armed one with great strength, the perfect and popular youth, ruler of rulers, chosen of Ptah and Nun, the father of the gods" |

— | — | — | Tyberiyus Tiberius |

[15] |

| Caligula r. 37–41 |

Hor-Kanakht Iakhsetutraiah "The strong bull, the light of the sun and the moon's rays" |

— | — | Autukratur Heqaheqau Meriptahaset "Emperor and ruler of rulers, beloved by Ptah and Isis" |

Kyseres Kerunykes (Ankhdjet) "Caesar Germanicus, (living forever)" |

[16] | |

|

Claudius r. 41–54 |

Hor-Kanakht Djediakhshu(em)akhet "The strong bull of the stable moon on the horizon" (?) |

— | — | Autukratur Heqaheqau Meriasetptah "Emperor and ruler of rulers, beloved of Isis and Ptah" |

Tiberus Kludius Tiberius Claudius |

[17] |

|

Nero r. 54–68 |

Hor-Tjemaa Huikhasut Wernakhubaqet Heqaheqau Setepennenumerur "The sturdy-armed one who struck the foreign lands, victorious for Egypt, ruler or rulers, chosen of Nun who loves him" |

— | Heqaheqau Setepenptah Meriaset "Ruler of rulers, chosen by Ptah, beloved of Isis" |

Autukratur Nerun Emperor Nero |

Nerun Nero |

[17] |

| Galba r. 68–69 |

— | — | — | Saruwu Galbas Autukratur Serviu(s) Galba, Emperor |

— | [17] | |

| Otho r. 69 |

— | — | — | — | Markuz Autnuz Marcus Otho |

[18] | |

| There are no known traces of the brief reign of Vitellius (r. 69) in Egypt.[7] | |||||||

| Vespasian r. 69–79 |

— | — | — | — | Wesbapsiyanas Vespasianus |

[19] | |

| Titus r. 79–81 |

Hor-Hununefer Benermerut "The perfect and popular youth" |

— | — | Iutagretar Tituz Kaisarus Emperor Titus Caesar |

Tytus Titus |

[20] | |

|

Domitian r. 81–96 |

Hor-Hununekhet Itiemsekhemef "The mighty youth, his power will be stronger" (?) |

Userrenput Aanakhtu "Rich in years and great of victories" |

Horzaaset Merinetjeruneb(u) "Horus, son of Isis, beloved of the gods" (?) |

— | Tomety Sebast Kermenyqes "The Vener(able) Domi(ni)ti(anus) Germanicus" |

[20] |

| Nerva r. 96–98 |

— | — | — | — | Nerwis(er) Netikhu Nerva Augustus |

[20] | |

|

Trajan r. 98–117 |

— | — | — | Autukratur Kaisarez Nerwauys Emperor Caesar Nerva(s) |

Kermenyq(es) Takyqu(nes) Ankhdjet "Germanic(us) Dacia(nus), living forever" |

[21] |

| Hadrian r. 117–138 |

— | — | — | — | Hetranez Qezer Hadrianus Caesar |

[22] | |

| Antoninus Pius r. 138–161 |

— | — | — | Autugratur Kyserez Tetesa A(b)luis Atrinuiz Emperor Caesar Titus Aelius Hadrianus |

Anutantnez Netikhu Ankhdjet "Antoninus Augustus, living forever" |

[23] | |

| Lucius Verus r. 161–169 |

— | — | — | — | Luky Aureli Weraa Ankhdjet "Luci(us) Aureli(us), great life forever" |

[24] | |

| Marcus Aurelius r. 161–180 |

— | — | — | Autekreter Kezrasa Merk Aureli Anutaninui Emperor Caesar Marc(us) Aureli(us) Antoninu(s) |

Aurely Anudenyny Aureli(us) Antoninu(s) |

[25] | |

| Commodus r. 180–192 |

— | — | — | — | Merquz Auryz Qemedez Sanutatataynusesa Marcus Aur(el)ius Commodus Antoninus |

[26] | |

| Pertinax[b] r. 193 |

— | — | — | — | — | [27] | |

| Didius Julianus (r. 193), who succeeded Pertinax in Rome, was not acknowledged in Egypt.[27] | |||||||

| Pescennius Niger[c] r. 193 |

— | — | — | — | — | [27] | |

| Septimius Severus r. 193–211 |

— | — | — | — | Zaweruis(er) Netikhu Severus Augustus |

[28] | |

|

Caracalla r. 211–217 |

— | — | — | — | Kaimedjus(er) Antanynus Netikhu Commodus Antoninus Augustus |

[29] |

| Geta r. 211 |

— | — | — | — | Get Netikhu Get(a) Augustus |

[30] | |

| Macrinus r. 217–218 |

— | — | — | — | Mikrynu Netikhu Macrinu(s) Augustus |

[31] | |

| Diadumenian r. 218 |

— | — | — | — | [Di]yatumenianez Diadumenianus |

[30] | |

| Elagabalus (r. 218–222), who succeeded Macrinus and Diadumenian, is not mentioned in any surviving Egyptian sources.[27] | |||||||

| Severus Alexander[d] r. 222–235 |

— | — | — | — | — | [32] | |

| The ephemeral emperors Maximinus Thrax (r. 235–238), Gordian I (r. 238), Gordian II (r. 238), Pupienus (r. 238), Balbinus (r. 238) and Gordian III (r. 238–244) did little of consequence in Egypt and are unrecorded in surviving Egyptian documents.[33] | |||||||

| Philip r. 244–249 |

— | — | — | — | Peshylupashes Netikhu Philippus Augustus |

[34] | |

| Decius r. 249–251 |

— | — | — | — | Dekes(ab) Netikhu Decius Augustus |

[35] | |

| Trebonianus Gallus[e] r. 251–253 |

— | — | — | — | — | [32] | |

| Aemilian[f] r. 253 |

— | — | — | — | — | [32] | |

| Valerian r. 253–260 |

— | — | — | — | Waylerinez Valerianus |

[37] | |

| Macrianus Minor[g] r. 260–261 |

— | — | — | — | — | [38] | |

| Quietus[h] r. 260–261 |

— | — | — | — | — | [38] | |

| Lucius Mussius Aemilianus[i] r. 261–262 |

— | — | — | — | — | [39] | |

| Gallienus[j] r. 262–268 |

— | — | — | — | — | [39] | |

| Few records survive from Egypt survive from the early 270s; composing the reigns of Claudius Gothicus (r. 268–270), Quintillus (r. 270), Aurelian (r. 270–275) and Tacitus (r. 275–276), though they were presumably recognised. Throughout most of 271, Egypt was occupied by Zenobia of the Palmyrene Empire, until the province was retaken by Aurelian. The brief reign of emperor Florian (r. 276) was explicitly rejected in Egypt, with the Egyptian legions backing Probus instead.[40] | |||||||

| Probus r. 276–282 |

— | — | — | — | — | [40] | |

| Emperors Carus (r. 282–283), Carinus (r. 283–285) and Numerian (r. 283–284) are not recorded in Egyptian sources.[40] | |||||||

| Diocletian r. 284–305 |

— | — | — | — | [Di][a]gliutziayun Diocletian(us) |

[41] | |

| Maximian r. 286–305 |

— | — | — | — | Miugzymiyaniu Maximianu(s) |

[42] | |

| Galerius r. 305–311 |

— | — | — | — | Kuzerez Ieiah Miahkzymyiah Caesar Ju(l)i(us) Maximiu(s) |

[42] | |

| Maximinus Daza r. 311–313 |

— | — | — | — | Quysarez Iwaylurez Maanuz Caesar Valer(i)us (Maxi)minus |

[43] | |

| The last aggressively Pagan emperor to control Egypt, Maximinus Daza was the last Roman emperor to be acknowledged in hieroglyphic texts. Although royal cartouches are recorded from later times (the last known cartouche being from the reign of Constantius II in 340), the pagan Egyptians posthumously used cartouches of Diocletian, rather than acknowledging the later Christian emperors.[44] | |||||||

Notes[]

- ^ The last dynasty identified with a number by most egyptologists is the Thirty-first Dynasty (when the Persians ruled Egypt for the second time). If the Romans are numbered as the "Thirty-fourth Dynasty", the Argead dynasty of Alexander the Great is considered the Thirty-second Dynasty and the Ptolemaic Kingdom is considered the Thirty-third Dynasty.

- ^ Pertinax's brief reign was recognised in Egypt just 22 days before he was assassinated.[27] No known Pharaonic titles of Pertinax survive.[24]

- ^ Pescennius Niger, most often regarded as a Roman usurper, was the recognised claimant in Egypt during the Year of the Five Emperors.[27] No known Pharaonic titles of Pescennius Niger survive.[24]

- ^ Severus Alexander's rule was recognised in Egypt, but very few Egyptian sources (only a handful of papyrus documents) record his reign.[27] No known Pharaonic titles of Severus Alexander survive.[30]

- ^ Trebonianus Gallus was recognised in Egypt, as attested by official documents and coins minted in Alexandria.[36] No known Pharaonic titles of Trebonianus Gallus survive.[30]

- ^ Aemilianus was recognised in Egypt, as attested by official documents and coins minted in Alexandria.[36] No known Pharaonic titles of Aemilianus survive.[30]

- ^ Macrianus Minor was proclaimed emperor alongside his brother Quietus in 260. They are typically regarded as usurpers, but were recognised in Egypt.[38] No known Pharaonic titles of Macrianus Minor survive.[30]

- ^ Quietus was proclaimed emperor alongside his brother Macrianus Minor in 260. They are typically regarded as usurpers, but were recognised in Egypt.[38] No known Pharaonic titles of Quietus survive.[30]

- ^ The usurper Lucius Mussius Aemilianus was proclaimed emperor in Egypt.[39] No known Pharaonic titles of Lucius Mussius Aemilianus survive.[30]

- ^ Gallienus was recognised in Egypt, as it was his supporters who ousted and killed the usurper Lucius Mussius Aemilianus.[39] No known Pharaonic titles of Gallienus survive.[30]

References[]

- ^ Rossini 1989, p. 6.

- ^ a b Loftie 2017.

- ^ Scott 1933, pp. 7–49.

- ^ Marinelli 2017.

- ^ Minas-Nerpel & Pfeiffer 2008, pp. 265–298.

- ^ Wasson 2016.

- ^ a b Ritner 1998, p. 13.

- ^ Ritner 1998, pp. 13–14.

- ^ Ritner 1998, p. 14.

- ^ O'Neill 2011.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 248–267.

- ^ Vernus & Yoyotte 2003, pp. 238–256.

- ^ Reid 2003, pp. 284.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 248–249; Ritner 1998, p. 12.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 252–253; Ritner 1998, pp. 12–13.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 252–253; Ritner 1998, p. 13.

- ^ a b c von Beckerath 1999, pp. 254–255; Ritner 1998, p. 13.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 256–257; Ritner 1998, p. 13.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 256–257; Ritner 1998, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c von Beckerath 1999, pp. 256–257; Ritner 1998, p. 14.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 258–259; Ritner 1998, pp. 14–15.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 258–261; Ritner 1998, pp. 15–16.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 260–261; Ritner 1998, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c von Beckerath 1999, pp. 262–263.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 262–265; Ritner 1998, p. 17.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 262–263; Ritner 1998, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c d e f g Ritner 1998, p. 18.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 262–263; Ritner 1998, pp. 18–19.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265; Ritner 1998, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265; Ritner 1998, p. 20.

- ^ a b c Ritner 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Ritner 1998, p. 21.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265; Ritner 1998, p. 21.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265; Ritner 1998, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Ritner 1998, p. 22.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265; Ritner 1998, p. 22.

- ^ a b c d Ritner 1998, pp. 22–23.

- ^ a b c d Ritner 1998, p. 23.

- ^ a b c von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265; Ritner 1998, p. 23.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 264–265; Ritner 1998, pp. 23–25.

- ^ a b von Beckerath 1999, pp. 266–267.

- ^ von Beckerath 1999, pp. 266–267; Ritner 1998, pp. 25–26.

- ^ Ritner 1998, pp. 26–28.

Cited bibliography[]

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Deutscher Kunstverlag. ISBN 978-3422008328.

- Loftie, William John (2017). A Ride in Egypt. Jazzybee Verlag.

- Minas-Nerpel, Martina; Pfeiffer, Stefan (2008), "Establishing Roman rule in Egypt: The trilingual stela of C. Cornelius Gallus from Philae", Proceedings of the International Conference, Hildesheim, Roemer- and Plizaeus-Museum: 265–298

- O'Neill, Sean J. (2011), "The Emperor as Pharaoh: Provincial Dynamics and Visual Representations of Imperial Authority in Roman Egypt, 30 B.C. - A.D. 69", Dissertions of the University of Cincinnati

- Reid, Donald Malcolm (2003). Whose Pharaohs? Archaeology, Museums, and Egyptian National Identity from Napoleon to World War I. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520240698.

- Ritner, Robert K. (1998). "Egypt under Roman rule: the legacy of Ancient Egypt" (PDF). In Petry, Carl F. (ed.). The Cambridge History of Egypt. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521471370.

- Rossini, Stéphane (1989). Egyptian Hieroglyphics: How to Read and Write Them. Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486260136.

- Scott, Kenneth (1933), "The Political Propaganda of 44-30 B. C.", Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, 11: 265–298, doi:10.2307/4238573, JSTOR 4238573

- Vernus, Pascal; Yoyotte, Jean (2003). The Book of the Pharaohs. Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801440502.

Cited web sources[]

- Marinelli, Christina. "Stories in Stone: How an Egyptian Temple Tells Its Story". Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- Wasson, Donald L. "Roman Egypt - World History Encyclopedia". Retrieved 2 August 2019.

- Roman Egypt

- Dynasties of ancient Egypt

- Roman pharaohs