Gordian I

| Gordian I | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

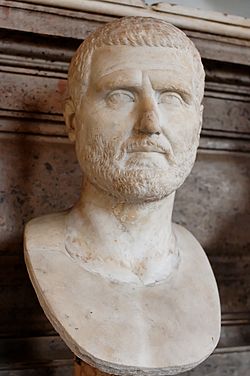

Bust, Capitoline Museums, Rome | |||||||||

| Roman emperor | |||||||||

| Reign | c. 22 March – 12 April 238[1] | ||||||||

| Predecessor | Maximinus Thrax | ||||||||

| Successor | Pupienus and Balbinus | ||||||||

| Co-emperor | Gordian II | ||||||||

| Born | c. 159 possibly Phrygia | ||||||||

| Died | 12 April 238 (aged 79) Carthage, Africa Proconsularis | ||||||||

| Spouse | Unknown, possibly Fabia Orestilla[2] | ||||||||

| Issue | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Dynasty | Gordian | ||||||||

| Father | Unknown, possibly Maecius Marullus[5] or Marcus Antonius[6] | ||||||||

| Mother | Unknown, possibly Ulpia Gordiana[5] or Sempronia Romana[6] | ||||||||

| Part of a series on Roman imperial dynasties |

| Year of the Six Emperors |

|---|

| 238 AD |

|

Gordian I (Latin: Marcus Antonius Gordianus Sempronianus Romanus Africanus; c. 159 AD[7] – mid April 238 AD) was Roman Emperor for 21 days with his son Gordian II in 238, the Year of the Six Emperors. Caught up in a rebellion against the Emperor Maximinus Thrax, he was defeated by forces loyal to Maximinus, and he committed suicide after the death of his son.

Family and background[]

Little is known about the early life and family background of Gordian I. There is no reliable evidence on his family origins.[8] Gordian I was said to be related to prominent Senators of his time.[9] His praenomen and nomen Marcus Antonius suggested that his paternal ancestors received Roman citizenship under the Triumvir Mark Antony, or one of his daughters, during the late Roman Republic.[9] Gordian’s cognomen ‘Gordianus’ also indicates that his family origins were from Anatolia, more specifically Galatia or Cappadocia.[10]

According to the Augustan History, his mother was a Roman woman called Ulpia Gordiana and his father was the Senator Maecius Marullus.[5] While modern historians have dismissed his father's name as false, there may be some truth behind the identity of his mother. Gordian's family history can be guessed through inscriptions. The name Sempronianus in his name, for instance, may indicate a connection to his mother or grandmother. In Ankara, Turkey, a funeral inscription has been found that names a Sempronia Romana, daughter of a named Sempronius Aquila (an imperial secretary).[9] Romana erected this undated funeral inscription to her husband (whose name is lost) who died as a praetor-designate.[8] Gordian might have been related to the gens Sempronia.

French historian Christian Settipani identified Gordian I's parents as Marcus Antonius (b. ca 135), tr. pl., praet. des., and wife Sempronia Romana (b. ca 140), daughter of Titus Flavius Sempronius Aquila (b. ca 115), Secretarius ab epistulis Graecis, and wife Claudia (b. ca 120), daughter of an unknown father and his wife Claudia Tisamenis (b. ca 100), sister of Herodes Atticus.[6] It appears in this family tree that the person who was related to Herodes Atticus was Gordian I's mother or grandmother and not his wife.[9]

Also according to the Augustan History, the wife of Gordian I was a Roman woman called Fabia Orestilla,[2] born circa 165, whom the Augustan History claims was a descendant of the Emperors Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius through her father Fulvus Antoninus.[2][11] Modern historians have dismissed this name and her information as false.[8]

With his wife, Gordian I had at least two children: a son of the same name [12] and a daughter, Antonia Gordiana (who was the mother of the future Emperor Gordian III).[13] His wife died before 238 AD. Christian Settipani identified her parents as Marcus Annius Severus, who was a Suffect Consul, and his wife Silvana, born circa 140 AD, who was the daughter of Lucius Plautius Lamia Silvanus and his wife Aurelia Fadilla, the daughter of Antoninus Pius and wife Annia Galeria Faustina or Faustina the Elder.[6]

Early life[]

Gordian steadily climbed the Roman imperial hierarchy when he became part of the Roman Senate. His political career started relatively late in his life[8] and his early years were probably spent in rhetoric and literary studies.[9] As a military man, Gordian commanded the Legio IV Scythica when the legion was stationed in Syria.[9] He served as governor of Roman Britain in 216 AD and was a Suffect Consul sometime during the reign of Elagabalus.[8] Inscriptions in Roman Britain bearing his name were partially erased suggesting some form of imperial displeasure during this role.[14]

While he gained unbounded popularity on account of the magnificent games and shows he produced as aedile,[15] his prudent and retired life did not excite the suspicion of Caracalla, in whose honor he wrote a long epic poem called Antoninias.[16][17]Gordian certainly retained his wealth and political clout during the chaotic times of the Severan dynasty which suggests a personal dislike for intrigue. Philostratus dedicated his work Lives of the Sophists to either him or his son, Gordian II.[18]

Rise to power[]

During the reign of Alexander Severus, Gordian I (who was by then in his late sixties), after serving his Suffect Consulship prior to 223, drew lots for the proconsular governorship of the province of Africa Proconsularis[8][19] which he assumed in 237.[20] However, prior to the commencement of his promagistrature, Maximinus Thrax killed Alexander Severus at Moguntiacum in Germania Inferior and assumed the throne.[21]

Maximinus was not a popular emperor and universal discontent increased due to his oppressive rule.[22] It culminated in a revolt in Africa in 238 AD. After, Maximinus' fiscal curator was murdered in a riot, people turned to Gordian and demanded that he accept the dangerous honor of the imperial throne.[3] Gordian, after protesting that he was too old for the position, eventually yielded to the popular clamour and assumed both the purple and the cognomen Africanus.[23]

According to Edward Gibbon:

An iniquitous sentence had been pronounced against some opulent youths of [Africa], the execution of which would have stripped them of far the greater part of their patrimony. (…) A respite of three days, obtained with difficulty from the rapacious treasurer, was employed in collecting from their estates a great number of slaves and peasants blindly devoted to the commands of their lords and armed with the rustic weapons of clubs and axes. The leaders of the conspiracy, as they were admitted to the audience of the procurator, stabbed him with the daggers concealed under their garments, and, by the assistance of their tumultuary train, seized on the little town of Thysdrus, and erected the standard of rebellion against the sovereign of the Roman empire. (...) Gordianus, their proconsul, and the object of their choice [as emperor], refused, with unfeigned reluctance, the dangerous honour, and begged with tears that they should suffer him to terminate in peace a long and innocent life, without staining his feeble age with civil blood. Their menaces compelled him to accept the Imperial purple, his only refuge indeed against the jealous cruelty of Maximin (...).[24]

Due to his advanced age, he insisted that his son be associated with him.[25] A few days later, Gordian entered the city of Carthage with the overwhelming support of the population and local political leaders.[26] Gordian I sent assassins to kill Maximinus' praetorian prefect, [27] and the rebellion seemed to be successful.[28] Gordian, in the meantime, had sent an embassy to Rome, under the leadership of Publius Licinius Valerianus,[29] to obtain the Senate’s support for his rebellion.[28] The Senate confirmed the new emperor on 2 April and many of the provinces gladly sided with Gordian.[30]

Opposition came from the neighboring province of Numidia.[3] Capelianus, governor of Numidia and a loyal supporter of Maximinus Thrax, held a grudge against Gordian[30] and invaded the African province with the only legion stationed in the region, III Augusta, and other veteran units.[31] Gordian II, at the head of a militia army of untrained soldiers, lost the Battle of Carthage and was killed,[30] and Gordian I took his own life by hanging himself with his belt.[32] The Gordians had reigned only three weeks.[33][34] Gordian was the first emperor to commit suicide since Otho in 69 during The Year of the Four Emperors.

Legacy[]

Gordian's positive reputation can be attributed to his reportedly amiable character. Both he and his son were said to be fond of literature, even publishing their own voluminous works.[24] While they were strongly interested in intellectual pursuits, they possessed neither the necessary skills nor resources to be considered able statesmen or powerful rulers. Having embraced the cause of Gordian, the Senate was obliged to continue the revolt against Maximinus following Gordian's death, appointing Pupienus and Balbinus as joint emperors.[35] Nevertheless, by the end of 238, the recognised emperor would be Gordian III, Gordian's grandson.[35]

Family tree[]

| previous Maximinus Thrax Roman Emperor 235–238 | Pupienus Roman Emperor 238 | Gordian I Roman Emperor 238 ∞ (?) Fabia Orestilla | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Balbinus Roman Emperor 238 | Gordian II co-emperor 238 | Antonia Gordiana | (doubted) Junius Licinius Balbus consul suffectus | Gaius Furius Sabinius Aquila Timesitheus praetorian prefect | next Philip the Arab Roman Emperor 244–249 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Gordian III Roman Emperor 238 | Furia Sabinia Tranquillina | Philip II Roman Emperor co-emperor 247–249 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References[]

- ^ These dates are just for reference, the exact chronology of events is unknown. See: Rea, J. (1972). "O. Leid. 144 and the Chronology of A.D. 238". Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 9, 1-19.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians, 17:4

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Southern, p. 86.

- ^ Cooley, Alison E. (2012). The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy. Cambridge University Press. p. 497. ISBN 978-0-521-84026-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians, 2:2

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Settipani, "Continuité gentilice et continuité sénatoriale dans les familles sénatoriales romaines à l'époque impériale"

- ^ Gordian I, A Dictionary of the Roman Empire, ed. Matthew Bunson, (Oxford University Press, 1995), 183.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Meckler, Gordian I

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Birley, pg. 340

- ^ Peuch, Bernadette, "Orateurs et sophistes grecs dans les inscriptions d'époque impériale", (2002), pg. 128

- ^ Krawczuk, Aleksander (1998). Poczet cesarzowych Rzymu. Warszawa: Iskry. p. 147. ISBN 83-244-0021-4. Archived from the original on 7 July 2018. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- ^ Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians, 17:1

- ^ Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians, 4:2

- ^ Birley, pg. 339

- ^ Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians, 3:5

- ^ Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians, 3:3

- ^ Kemezis, Adam M (2014). Greek Narratives of the Roman Empire Under the Severans: Cassius Dio, Philostratus and Herodian. Cambridge University Press.

- ^ "Grant, The Roman Emperors", pg. 140

- ^ Herodian, 7:5:2

- ^ Birley, pg. 333

- ^ Potter, pg. 167

- ^ Cope, Geoffrey. Gordian I, 2, & 3 (238AD-244AD).

- ^ Herodian, 7:5:8. "After Maximinus had completed three years as emperor [after 22 March 238], the people of Africa first took up arms and touched off a serious revolt for one of those trivial reasons which often prove fatal to a tyrant."

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gibbon, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. I, Ch. 7

- ^ Adkins, Lesley and Adkins Roy A., Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome: Updated Edition, p. 27: Gordian II was "Proclaimed co-emperor on 22 March 238" with Gordian II

- ^ Herodian, 7:6:2

- ^ Laale, Hans Willer (2011). Ephesus (Ephesos): An Abbreviated History from Androclus to Constantine X. WestBow Press. ISBN 978-144-971-618-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Potter, pg. 169

- ^ Zosimus, 1:11

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Potter, pg. 170

- ^ Herodian, 7.9.3

- ^ D'Epiro, Peter (2010). The Book of Firsts: 150 World-Changing People and Events, from Caesar Augustus to the Internet. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. ISBN 978-030-747-666-1.

- ^ Furius Dionysius Filocalus, Chronograph of 354, Part 16: "The two Gordians ruled for 20 days. They died in Africa.".

- ^ Joannes Zonaras xvii.17: "According to some they reigned about twenty-two days, but according to others not quite three months". He confuses the Gordians with Balbinus and Pupienus, thus the discrepancy.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Southern, p. 87.

Sources[]

Primary sources[]

- Herodian, Roman History, Book 7

- Historia Augusta, The Three Gordians

- Aurelius Victor, Epitome de Caesaribus

- Joannes Zonaras, Compendium of History extract: Zonaras: Alexander Severus to Diocletian: 222–284

- Zosimus, Historia Nova

Secondary sources[]

- Adkins, Lesley; Adkins, Roy A. (2004) [1994]. Handbook to Life in Ancient Rome: Updated Edition. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 0-8160-5026-0.

- Birley, Anthony (2005), The Roman Government in Britain, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-925237-4

- Gibbon, Edward, Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1888)

- Grasby, K.D. (1975). "The Age, Ancestry, and Career of Gordian I". Classical Quarterly. 25 (1): 123–130. doi:10.1017/S000983880003295X. JSTOR 638250.

- Meckler, Michael L., Gordian I (238 A.D.), De Imperatoribus Romanis (2001)

- Potter, David Stone, The Roman Empire at Bay, AD 180–395, Routledge, 2004

- Settipani, Christian, Continuité gentilice et continuité sénatoriale dans les familles sénatoriales romaines à l'époque impériale, 2000

- Southern, Pat (2015) [2001]. The Roman Empire from Severus to Constantine (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-73807-1.

- Syme, Ronald, Emperors and Biography, Oxford University Press, 1971

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gordianus I. |

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Gordian". Encyclopædia Britannica. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 247.

- 159 births

- 238 deaths

- 3rd-century Roman emperors

- Crisis of the Third Century

- Suffect consuls of Imperial Rome

- Roman governors of Britain

- Deified Roman emperors

- Ancient Romans who committed suicide

- Suicides by hanging in Tunisia

- Antonii

- Gordian dynasty