Romeo and Juliet (1936 film)

| Romeo and Juliet | |

|---|---|

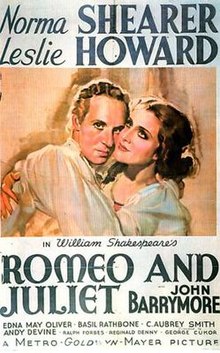

1936 US Theatrical Poster | |

| Directed by | George Cukor |

| Written by |

|

| Based on | Romeo and Juliet 1597 play by William Shakespeare |

| Produced by | Irving Thalberg |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | William H. Daniels |

| Edited by | Margaret Booth |

| Music by | Herbert Stothart |

| Distributed by | Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer |

Release date |

|

Running time | 125 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2 million[1][2] |

| Box office |

|

Romeo and Juliet is a 1936 American film adapted from the play by William Shakespeare, directed by George Cukor from a screenplay by Talbot Jennings. The film stars Leslie Howard as Romeo and Norma Shearer as Juliet,[3][4] and the supporting cast features John Barrymore, Basil Rathbone, and Andy Devine.

The New York Times selected the film as one of the "Best 1,000 Movies Ever Made", calling it "a lavish production" that "is extremely well-produced and acted."[5]

Plot summary[]

This section needs expansion. You can help by . (March 2021) |

Cast[]

- Norma Shearer as Juliet

- Leslie Howard as Romeo

- John Barrymore as Mercutio

- Edna May Oliver as the Nurse

- Basil Rathbone as Tybalt

- C. Aubrey Smith as Lord Capulet

- Andy Devine as Peter, a servant

- Conway Tearle as Escalus – Prince of Verona

- Ralph Forbes as Paris

- Henry Kolker as Friar Laurence

- Robert Warwick as Lord Montague

- Virginia Hammond as Lady Montague

- Reginald Denny as Benvolio

- Violet Kemble-Cooper as Lady Capulet

Uncredited cast includes Wallis Clark, Katherine DeMille, Fred Graham, Dorothy Granger, Ronald Howard, Lon McCallister, and Ian Wolfe.[6]

Production[]

Development[]

Producer Irving Thalberg pushed MGM for five years to make a film of Romeo and Juliet, in spite of studio head Louis B. Mayer's resistance. Mayer believed that the mass audience considered the Bard over their heads, and also he was concerned with the studio's budget constraints during the early years of the Great Depression. It was only when Jack L. Warner announced his intention to film Max Reinhardt's A Midsummer Night's Dream at Warner Bros. that Mayer, not to be outdone, gave Thalberg the go-ahead.[7] The success of a 1934 Broadway revival also encouraged the idea of a film version. It starred Katharine Cornell as Juliet, Basil Rathbone as Romeo, Brian Aherne as Mercutio, and Edith Evans as The Nurse.[8] Rathbone is the only actor from the 1934 revival to appear in the film, albeit in the role of Tybalt rather than Romeo. On the stage Tybalt was played by nineteen year old Orson Welles.

Thalberg's stated intention was "to make the production what Shakespeare would have wanted had he possessed the facilities of cinema."[9] He went to great lengths to establish authenticity and the film's intellectual credentials: researchers were sent to Verona to take photographs for the designers; the paintings of Botticelli, Bellini, Carpaccio, and Gozzoli were studied to provide visual inspiration; and two academic advisers (John Tucker Murray of Harvard and William Strunk Jr. of Cornell) were flown to the set, with instructions to criticise the production freely.[10]

Production[]

Thalberg had only one choice for director: George Cukor, who was known as "the women's director". Thalberg's vision was that the performance of Norma Shearer, his wife, would dominate the picture.[10] In addition to such noted Shakespearean actors as Howard and Barrymore, Thalberg cast many screen actors and brought in East Coast drama coaches (such as Frances Robinson Duff who coached Shearer) to teach them. In consequence, actors previously noted for naturalism were found to give more stage-like performances.[10] The shoot extended to six months, and the budget reached $2 million, MGM's most expensive sound film up to that time.[11]

As in most Shakespeare-based screenplays, Cukor and his screenwriter Talbot Jennings cut much of the original play, using around 45% of it.[12] Many of these cuts are common ones in the theatre, such as the second chorus[13] and the comic scene of Peter with the musicians.[12][14] Others are filmic: designed to replace words with action, or rearranging scenes in order to introduce groups of characters in longer narrative sequences. Jennings retained more of Shakespeare's poetry for the young lovers than any of his big-screen successors. Several scenes are interpolated, including three sequences featuring Friar John in Mantua. In contrast, the role of Friar Laurence (an important character in the play) is much reduced.[15] A number of scenes are expanded as opportunities for visual spectacle, including the opening brawl (set against the backdrop of a religious procession), the wedding and Juliet's funeral. The party scene, choreographed by Agnes de Mille, includes Rosaline (an unseen character in Shakespeare's script) who rebuffs Romeo.[12] The role of Peter is enlarged, and played by Andy Devine as a faint-hearted bully. He speaks lines which Shakespeare gave to other Capulet servants, making him the instigator of the opening brawl.[12][16] The film includes two songs drawn from other plays by Shakespeare: "Come Away Death" from Twelfth Night and "Honour, Riches, Marriage, Blessing" from The Tempest.[17]

Clusters of images are used to define the central characters: Romeo is first sighted leaning against a ruined building in an arcadian scene, complete with a pipe-playing shepherd and his dog; the livelier Juliet is associated with Capulet's formal garden, with its decorative fish pond.[18]

Premiere[]

On the night of the Los Angeles premiere of the film at the Carthay Circle Theatre, legendary MGM producer Irving Thalberg, husband of Norma Shearer, died at age 37. The stars in attendance were so grief-stricken that publicist Frank Whitbeck, standing in front of the theater, abandoned his usual policy of interviewing them for a radio broadcast as they entered and simply announced each one as he or she arrived.[19]

Reception[]

Box office[]

According to MGM records, the film earned $2,075,000 worldwide but because of its high production cost lost $922,000.[2]

Critical reaction[]

Some critics liked the film, but on the whole, neither critics nor the public responded enthusiastically. Graham Greene wrote that he was "less than ever convinced that there is an aesthetic justification for filming Shakespeare at all... the effect of even the best scenes is to distract."[20][21] "Ornate but not garish, extravagant but in perfect taste, expansive but never overwhelming, the picture reflects great credit upon its producers and upon the screen as a whole", wrote Frank Nugent in a positive review for The New York Times. "It is a dignified, sensitive and entirely admirable Shakespearean—not Hollywoodean—production."[22] Variety called the film a "faithful" adaptation with "very beautiful" costuming, but also found it "not too imaginative" and "a long sit" at over two hours.[23] Film Daily raved that it was a "superb and important achievement" and "one of the most important contributions to the screen since the inception of talking pictures."[24] John Mosher of The New Yorker called it "a very definite achievement" but "somewhat cumbersome", writing "This is a good, sensible presentation of 'Romeo and Juliet,' but it won't be one you'll hark back to when you are discussing the movies as great art, if you do ever discuss them as great art."[25]

Many moviegoers considered the film too "arty", staying away as they had from Warner's A Midsummer Night's Dream a year before and leading Hollywood to abandon the Bard for over a decade.[26] The film nevertheless received four Oscar nominations [27] and for many years was considered one of the great MGM classics. In his annual Movie and Video Guide, Leonard Maltin gives both this film version and the popular 1968 Franco Zeffirelli version (with Olivia Hussey and Leonard Whiting) an equal rating of three-and-a-half stars.

More recently, scholar Stephen Orgel describes Cukor's film as "largely miscast ... with a preposterously mature pair of lovers in Leslie Howard and Norma Shearer, and an elderly John Barrymore as a stagey Mercutio decades out of date."[28] Barrymore was in his fifties, and played Mercutio as a flirtatious tease.[18] Tybalt, often portrayed as a hot-headed troublemaker, is played by Basil Rathbone as stuffy and pompous.[29]

Subsequent film versions made use of "younger, less experienced but more photogenic actors"[18] in the central roles.[18] Cukor, interviewed in 1970, said of his film: "It's one picture that if I had to do over again, I'd know how. I'd get the garlic and the Mediterranean into it."[30]

Awards and honors[]

| Academy Award nominations | Nominee(s) |

|---|---|

| Best Picture | Irving Thalberg |

| Best Actress | Norma Shearer |

| Best Supporting Actor | Basil Rathbone |

| Best Art Direction | Art Direction and Interior Decoration: Cedric Gibbons, Fredric Hope, and Edwin B. Willis |

In 2002, the American Film Institute nominated this film for AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions.[31]

Legacy[]

A colour roll of 16mm Kodachrome filmed by co-star Leslie Howard during the opening exterior sequence with Howard and Reginald Denny in costume as the crew set up is featured in the 2016 documentary Leslie Howard: The Man Who Gave a Damn.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Glancy, H. Mark (1999). When Hollywood Loved Britain: The Hollywood 'British' Film 1939–1945. Manchester University Press. ISBN 0-7190-4852-4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ Variety film review; August 26, 1936, page 20.

- ^ Harrison's Reports film review; September 19, 1936, page 150.

- ^ Review in New York Times

- ^ Full cast and credits at Internet Movie Database

- ^ Brode, Douglas Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Today (2001, Berkeley Boulevard, New York, ISBN 0-425-18176-6) p.43

- ^ Romeo and Juliet revival, at the Martin Beck Theatre Dec. 20 1934-Feb. 1935; IBDb.com

- ^ Thalberg, Irving – quoted by Brode, p.44

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Brode, p.44

- ^ Brode, p. 45

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Tatspaugh, p.137

- ^ Romeo and Juliet II.0.1-14

- ^ Romeo and Juliet IV.v.96-141

- ^ Brode, p. 46

- ^ Romeo and Juliet I.i

- ^ Tatspaugh, Patricia "The Tragedy of Love on Film" in Jackson, Russell The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film (Cambridge University Press, 2000, ISBN 0-521-63975-1) p.137

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Tatspaugh, p.138

- ^ Higham, Charles (Dec 1994) [1993]. Merchant of Dreams: Louis B. Mayer, M.G.M., and the Secret Hollywood (paperback ed.). Dell Publishing. p. 289. ISBN 0-440-22066-1.

- ^ Greene, Graham (1972). Taylor, John Russell (ed.). The Pleasure Dome. Collected Film Criticism 1935-40. London, England: Martin Secker & Warburg Ltd. ISBN 978-0436187988.

- ^ Jackson, Russell, ed. (2007). "From Play-Script to Screenplay". The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0521866002.

- ^ Nugent, Frank S. (August 21, 1936). "Movie Review – Romeo and Juliet". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

- ^ "Romeo and Juliet". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc. August 26, 1936. p. 20.

- ^ "Romeo and Juliet". Film Daily. New York: Wid's Films and Film Folk, Inc. July 16, 1936. p. 2.

- ^ Mosher, John (August 22, 1936). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York City: Condé Nast. p. 50.

- ^ Brode, p.48

- ^ Tatspaugh, p.136

- ^ Orgel, p.91

- ^ Brode, p.47

- ^ Tatspaugh, p.136, citing George Cukor. A fuller version of the quotation, used here, appears in Rosenthal, Daniel BFI Screen Guides: 100 Shakespeare Films (British Film Institute, London, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84457-170-3) p.209 (Note that these sources conflict on the date of this interview: Rosenthal says 1971.)

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved August 19, 2016.

External links[]

- Romeo and Juliet at IMDb

- Romeo and Juliet at the TCM Movie Database

- Romeo and Juliet at AllMovie

- Romeo and Juliet at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Romeo and Juliet at Rotten Tomatoes

- Romeo and Juliet at Virtual History

- George Cukor and cast going over script left to right: Edna Mae Oliver, Cukor, Norma Shearer, Leslie Howard, John Barrymore, Basil Rathbone, Violet Kemble-Cooper, ? unidentified, Henry Kolker

- 1936 films

- English-language films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- Films directed by George Cukor

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- Films based on Romeo and Juliet

- Films set in Italy

- Films produced by Irving Thalberg

- Films scored by Herbert Stothart

- American romantic drama films

- 1936 romantic drama films