Adam's Rib

| Adam's Rib | |

|---|---|

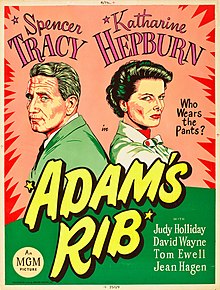

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | George Cukor |

| Written by | Ruth Gordon Garson Kanin |

| Produced by | Lawrence Weingarten |

| Starring | Spencer Tracy Katharine Hepburn |

| Cinematography | George J. Folsey |

| Edited by | George Boemler |

| Music by | Miklós Rózsa |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Loew's Inc.[1] |

Release date |

|

Running time | 101 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $1,728,000[2] |

| Box office | $3,947,000[2] |

Adam's Rib is a 1949 American romantic comedy-drama film directed by George Cukor from a screenplay written by Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin. It stars Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn as married lawyers who come to oppose each other in court. Judy Holliday co-stars as the third lead in her second credited movie role. Also featured are Tom Ewell, David Wayne, and Jean Hagen. The music was composed by Miklós Rózsa, and song "Farewell, Amanda" was written by Cole Porter.

The film was well received upon its release and is considered a classic romantic comedy, being nominated for both AFI's 100 Movies and Passions lists, and coming in at #22 on the AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs.

Plot[]

Doris Attinger follows her husband with a gun in Manhattan one day, suspecting he is having an affair with another woman. In her rage, she fires wildly and blindly around the room and at the couple multiple times. One of the bullets hits her husband in the shoulder. His lover escapes unscathed.

The following morning, the married New York lawyers Adam and Amanda Bonner read about the incident in the newspaper. Adam is an assistant district attorney, while Amanda is a solo-practicing defense attorney. They argue over the case. Amanda sympathizes with the woman, particularly noting the double standard that exists for men and women regarding adultery. Adam thinks Doris is guilty of attempted murder. When Adam arrives at work, he learns that he has been assigned to prosecute the case. When Amanda hears this, she seeks out Doris and becomes her defense lawyer.

Amanda bases her case on the belief that women and men are equal, and that Doris had been forced into the situation by her husband's adultery and emotional abuse. Adam thinks Amanda is showing contempt for the law, since there should never be any excuse for such criminal behavior. Tension increasingly builds at home as the two battle each other in court. The situation comes to a head as Adam feels humiliated during the trial when Amanda encourages one of her witnesses, a woman weightlifter, to lift him overhead. Later at home that evening, Adam still angry, gives Amanda an ear full; he doesn't want to be married to a liberated "new woman." Having just packed his bags, he storms out of their apartment. When the verdict is returned, Amanda's plea to the jury to "judge this case as you would if the sexes were reversed" proves successful, and Doris is acquitted.

That night, Adam, who has left their upper-floor apartment, looks through its window and sees the silhouettes of his wife Amanda and their neighbor Kip Lurie, a popular singer, songwriter and piano player who has shown a keen interest in Amanda all along, and repeatedly taunted Adam, as the two of them seem to be dancing and drinking together. Adam breaks into the apartment enraged, pointing a gun at the pair. Amanda is horrified and says to Adam, "You've no right to do this – nobody does!" Adam feels he has proven his point about the injustice of Amanda's line of defense. He puts the gun in his mouth, as Amanda and Kip scream in terror. Then Adam bites a large piece off the gun and chews it. It is made of licorice. Amanda is furious with this prank and a three-way fight ensues.

Now in the midst of a divorce, Adam and Amanda reluctantly reunite for a meeting with their tax accountant. Going through their expenses for the year, they talk about their relationship in the past tense. They talk about the farm they own and recall burning the mortgage. Tears begin to roll down Adam's cheeks. Astonished and touched, Amanda gently bundles her sobbing husband out of the office and to the farm. That night, while they are getting ready for bed — in an antique, curtained four poster — Adam announces that he has been selected as the Republican nominee for County Court Judge. Amanda perches on the edge of the bed and jokes about running for the post as the Democratic candidate. Adam replies, no she won't, because then he would cry. He demonstrates how easily he can turn on the tears, remarking that men can do it too, they just don't think to. Amanda says that just goes to show that there is no difference between the sexes...Well, maybe there is a little difference. "You know what the French say," Adam declares 'Vive la différence!'...'Hurray for that little difference!'" as he jumps onto the bed and closes the curtains.

Cast[]

|

|

Production[]

The film's screen play was written specifically as a Tracy-Hepburn vehicle (their sixth film together) by Garson Kanin and actress Ruth Gordon, married script writers who were friends of the couple. In an article Garson Kanin wrote for the October/November 1989 issue of Memories: The Magazine of Then and Now, he noted “that Judy Holliday initially turned down her role in the film because she is called 'fatso' in the script.” [3] He also said that the story of Adam's Rib was based on the lives of Ruth Gordon's friends, Dorothy and William Dwight Whitney, and actor Raymond Massey.[3] The Whitneys were lawyers who ended up divorcing and marrying their respective clients in the high-profile divorce of Massey and his wife of 10 years, actress Adrienne Allen. Massey married his attorney, Dorothy Whitney, in 1939; their marriage lasted until her death in 1982. Allen married her lawyer, William Dwight Whitney, who died in 1973.[4] Kanin and Gordon saw great potential in the idea of married lawyers as adversaries, and the plot for Adam's Rib was developed. Other titles for the film were Love is Legal and Man and Wife.[3] The MGM front office quickly vetoed the latter as dangerously indiscreet.[5]

In the same article, Kanin recalls how Cole Porter refused to write a song for “Madelaine,” as Hepburn's character was originally named. Her name was changed to "Amanda,” and all was well. In June 1949, Hollywood Reporter wrote that Porter and MGM agreed to donate all profits from sales of the song "Farewell Amanda" to the Runyon Cancer Fund.

Although set in New York, Adam's Rib was filmed mainly on MGM's stages in Culver City, Los Angeles.[6] “According to contemporary sources, some filming took place on location in various parts of New York City, including the Women's House of Detention at Greenwich Avenue and Tenth Street, where, in the film, "Doris Attinger" is taken after shooting her husband, and at Ruth Gordon and Garson Kanin's farm at Newton, Connecticut.”[3]

According to TCM.com, “ Modern sources indicate that Hepburn deliberately allowed Holliday to steal the scenes in which they appeared together so that Holliday could show off her talent to Columbia executives, who were resisting the idea of casting her in a film version of the role she originated in Born Yesterday. ”[3]

Hepburn and Kanin encouraged Judy Holliday to play the role of Doris in the movie, which was used by Columbia Pictures president Harry Cohn as a screen test for the re-creation on film of her Broadway success in Kanin's play Born Yesterday. Receiving positive notices for Adam's Rib, Holliday was cast in the 1950 film version of Born Yesterday, for which she won the Academy Award for Best Actress.

It has been noted that there are unusually long takes in several scenes of the film, scenes where the camera does not move for minutes at a time. Most of these scenes show the principal characters arguing.[7]

Reception[]

According to MGM records, the film earned $2,971,000 in the US and Canada and $976,000 elsewhere, resulting in a profit of $826,000.[2][8]

Variety staff reviewing the film on December 31, 1949, praised the “...bright comedy success, belting over a succession of sophisticated laughs...This is the sixth Metro teaming of Tracy and Hepburn, and their approach to marital relations around their own hearth is delightfully saucy. A better realization on type than Holliday's portrayal of a dumb Brooklyn femme doesn't seem possible.”[9]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, Adam's Rib has a "Fresh" score of 96% based on 28 reviews, with an average rating of 8.04/10; the consensus for the film says: "Matched by Garson Kanin's witty, sophisticated screenplay, George Cukor, Spencer Tracy, and Katherine [sic] Hepburn are all in top form in the classic comedy Adam's Rib."[10]

Leonard Maltin gives the film 4 out of 4 stars, describing it as “One of Hollywood's greatest comedies about the battle of the sexes, with peerless Tracy and Hepburn supported by movie newcomers Holliday, Ewell, Hagen, and Wayne.”[11]

Awards and honors[]

Ruth Gordon (later of Rosemary's Baby and Harold and Maude fame) and Garson Kanin were nominated for the Academy Award for Best Story and Screenplay in 1951.

In 1992, the film was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[12][13][14]

The film is recognized by American Film Institute in these lists:

- 2000: AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs – #22[15]

- 2008: AFI's 10 Top 10:

- #7 Romantic Comedy Film[16]

AFI has also honored the film's stars, naming Katharine Hepburn the greatest American screen legend among females and Spencer Tracy #9 among males.

TV adaptation[]

Adam's Rib was adapted as a television sitcom in 1973 with Ken Howard and Blythe Danner. The series was canceled after 13 episodes.

References[]

- ^ Adam's Rib at the American Film Institute Catalog

- ^ Jump up to: a b c The Eddie Mannix Ledger, Los Angeles: Margaret Herrick Library, Center for Motion Picture Study.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "Adam's Rib (1949) - Notes - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Pace, Eric (September 20, 1993). "Adrianne Allen, 86, A British Specialist In Light Comedies". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ Kanin, Garson (1971). Tracy and Hepburn: An Intimate Memoir. New York: Viking. pp. 154–155. ISBN 0-670-72293-6.

- ^ The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations by Tony Reeves. The Titan Publishing Group. p. 12 [1] Archived June 25, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Higham, Charles; Greenberg, Joel (1968). Hollywood in the Forties. London: A. Zwemmer Limited. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-498-06928-4.

- ^ "Top Grossers of 1949". Variety. January 4, 1950. p. 59.

- ^ "Adam's Rib". Variety. January 1, 1950. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ [2] "Adam's Rib (1949) - Rotten Tomatoes". Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- ^ "Turner Classic Movies - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- ^ "National Film Registry" Archived April 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Library of Congress, accessed October 28, 2011.

- ^ Wharton, Andy Marx, Dennis; Marx, Andy; Wharton, Dennis (December 4, 1992). "Diverse pix mix picked". Variety. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "Complete National Film Registry Listing | Film Registry | National Film Preservation Board | Programs at the Library of Congress | Library of Congress". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved September 10, 2020.

- ^ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Laughs" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

- ^ "AFI's 10 Top 10: Top 10 Romantic Comedy". American Film Institute. Retrieved July 17, 2016.

External links[]

- Adam's Rib on TCM.com

- Adam's Rib on the American Film Institute Catalog

- Adam's Rib at IMDb

- Adam's Rib at AllMovie

- Adam's Rib at Rotten Tomatoes

- Adam's Rib essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 429-430 [3]

- 1949 films

- English-language films

- 1949 comedy-drama films

- 1949 romantic comedy films

- 1940s feminist films

- 1940s legal films

- American films

- American black-and-white films

- American courtroom films

- American feminist comedy films

- American romantic comedy films

- American romantic comedy-drama films

- Comedy of remarriage films

- Films about lawyers

- Films adapted into television shows

- Films scored by Miklós Rózsa

- Films directed by George Cukor

- Films set in New York City

- Films shot in Los Angeles

- Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer films

- United States National Film Registry films