Rotuma

Rotuma Island Rotuma | |

|---|---|

Flag | |

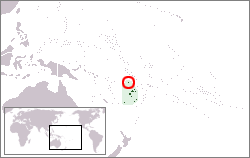

Location of Rotuma in Polynesia. | |

Schematic map of Rotuma indicating districts and main villages. | |

| Administrative center | Ahau 12°29.9′S 177°2.82′E / 12.4983°S 177.04700°E |

| Official languages |

|

| Ethnic groups | Rotuman |

| Demonym(s) | Rotuman |

| Government | Dependency of Fiji |

• Gagaj Pure (District officer) | Niumaia Masere |

• Gagaj Jeaman (Council chairman) | Tarterani Rigamoto |

| Independence from the United Kingdom as part of Fiji | |

• Date | October 10, 1970 |

| Area | |

• Total | 47 km2 (18 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2017 census | 1,594 |

| Currency | Fiji dollar (FJD) |

| Time zone | UTC+12 |

| Calling code | +679 |

Rotuma /roʊˈtuːmə/ is a Fijian dependency, consisting of Rotuma Island and nearby islets. The island group is home to a large and unique indigenous ethnic group which constitutes a recognisable minority within the population of Fiji, known as "Rotumans". Its population at the 2017 census was 1,594,[1] although many more Rotumans live on mainland Fijian islands, totaling 10,000.

Geography and geology[]

The Rotuma group of volcanic islands are located 646 kilometres (401 mi) (Suva to Ahau) north of Fiji. Rotuma Island itself is 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) long and 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) wide, with a land area of approximately 47 square kilometres (12,000 acres),[2] making it the 12th-largest of the Fiji islands. The island is bisected by an isthmus into a larger eastern part and a western peninsula. The isthmus is low and narrow, only 230 metres (750 ft) wide, and is the site of Motusa village (Ituʻtiʻu district). North of the isthmus is Maka Bay, and in the south is Hapmafau Bay. There is a large population of coral reefs in these bays, and there are boat passages through them.

Rotuma is a shield volcano made of alkali-olivine basalt and hawaiite, with many small cones. It reaches 256 metres (840 ft) above sea level at Mount Suelhof, near the center of the island. Satarua Peak, 166 metres (540 ft) high, lies near the eastern end of the island.[3] While they are very secluded from much of Fiji proper, the large reef and untouched beaches are renowned as some of the most beautiful in the Kingdom of Fiji.

There are several islands that lie between 50 metres (160 ft) and 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) distant from the main island, but are still within the fringing reef. They are:

- Solnohu (south)

- Solkope and (southeast)

- and (far southeast)

- Husia (Husiatiʻu) and (close southeast)

- and (Hạuatiʻu) (close together northeast).

There is also a separate chain of islands that lie between 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) and 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) to the northwest and west of Rotuma Island. In order, from northeast to southwest, these are:

The geological features of this island contribute to its national significance, as outlined in Fiji's Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.[5]

Climate[]

| hideClimate data for Rotuma (Ahau) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 34 (93) |

33 (91) |

34 (93) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

32 (90) |

33 (91) |

32 (90) |

34 (93) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 30.8 (87.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

30.5 (86.9) |

29.9 (85.8) |

29.7 (85.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

29.2 (84.6) |

29.4 (84.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

30.2 (86.4) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 27.6 (81.7) |

27.6 (81.7) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.1 (80.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

26.3 (79.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

26.8 (80.2) |

27.2 (81.0) |

27.5 (81.5) |

27.0 (80.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 24.8 (76.6) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.8 (76.6) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.2 (75.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.3 (75.7) |

24.5 (76.1) |

24.7 (76.5) |

24.6 (76.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 20 (68) |

21 (70) |

21 (70) |

22 (72) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

18 (64) |

20 (68) |

19 (66) |

17 (63) |

20 (68) |

20 (68) |

17 (63) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 345 (13.6) |

368 (14.5) |

348 (13.7) |

284 (11.2) |

295 (11.6) |

246 (9.7) |

213 (8.4) |

224 (8.8) |

236 (9.3) |

300 (11.8) |

318 (12.5) |

312 (12.3) |

3,489 (137.4) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 20 | 21 | 23 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 17 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 18 | 20 | 223 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 83 | 83 | 84 | 83 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 81 | 82 | 83 | 82 | 82 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 201.5 | 158.1 | 155.0 | 171.0 | 179.8 | 171.0 | 179.8 | 220.1 | 180.0 | 207.7 | 177.0 | 164.3 | 2,165.3 |

| Mean daily sunshine hours | 6.5 | 5.6 | 5.0 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.8 | 7.1 | 6.0 | 6.7 | 5.9 | 5.3 | 5.9 |

| Source: Deutscher Wetterdienst[6] | |||||||||||||

Flora and fauna[]

A 4,200-hectare (10,000-acre) area covering the main island and its small satellite islets is the Rotuma Important Bird Area. The Important Bird Area covers the entire range of the vulnerable Rotuma myzomela, and the Rotuman subspecies of Polynesian starling and Fiji shrikebill. Rotuma also supports isolated outlying populations of Crimson-crowned fruit dove and Polynesian triller. The offshore islets of Haʻatana, Hofliua and Hatawa have nationally significant seabird colonies.[7]

History[]

Linguistic evidence[]

Linguistic evidence suggests an original settlement from Fiji. Linguists include the Rotuman language in a subgroup with the languages of western Fiji, but Rotuman also has a large number of Polynesian loanwords, indicating later contact with Samoa and Tonga.

Origins in oral history[]

According to Rotuman oral history the islands' first inhabitants came from Samoa, led by a man named Raho. Shortly thereafter, additional settlers arrived from Tonga. Later, additional settlers came from Tonga and Kiribati. In the 1850s and 1860s, the Tongan prince Ma'afu claimed possession of Rotuma and sent his subordinates to administer the main island and its neighboring islets.[8]

In 1896, the scholar Friedrich Ratzel[9] recorded a Samoan legend about Samoans’ relationship to Rotuma:

"Thus the Samoans relate that one of their chiefs fished up Rotuma and planted coco-palm on it. But in a later migration the chief Tokaniua came that way with a canoe full of men and quarrelled with him about the prior right of possession."

European contact[]

The earliest known confirmed European sighting of Rotuma was in 1791, when Captain Edward Edwards and the crew of HMS Pandora landed in search of sailors who had disappeared following the Mutiny on the Bounty. Some scholars have suggested that the first European to sight the island was, instead, Pedro Fernandes de Queirós: His description of an island he sighted is consistent with the characteristics and location of Rotuma. However, this possibility has not been conclusively substantiated.

Mid-19th century[]

A favorite of whaling ships in need of reprovisioning, in the mid-nineteenth century Rotuma also became a haven for runaway sailors, some of whom were escaped convicts. Some of these deserters married local women and contributed their genes to an already heterogeneous pool; others met violent ends, reportedly at one another's hands. The first recorded whaler to visit was the Loper in 1825. The last known whaling visit was by the Charles W. Morgan in 1894.[10] Rotuma was visited as part of the United States Exploring Expedition in 1840.

Cession to Britain[]

Wesleyan teachers from Tonga arrived on Rotuma in June 1841, followed by Catholic Marists in 1847. The Roman Catholic missionaries withdrew in 1853 but returned in 1868. Conflicts between the two groups, fuelled by previous political rivalries among the chiefs of Rotuma's seven districts, resulted in hostilities that led the local chiefs in 1879 to ask Britain to annex the island group. On 5th November 1880, Rotuma was officially ceded to the United Kingdom,when the British flag was hoisted by Mr.Hugh Romilly. The event is annually celebrated as Rotuma Day.

Demographics[]

Although the island has been politically part of Fiji since 1881, Rotuman culture more closely resembles that of the Polynesian islands to the east, most noticeably Tonga, Samoa, Futuna, and Uvea. Because of their Polynesian appearance and distinctive language, Rotumans now constitute a recognizable minority group within the Republic of Fiji. The great majority of Rotumans (9,984 according to the 2007 Fiji census) now live elsewhere in Fiji, with 1,953 Rotumans remaining on Rotuma. Rotumans are culturally conservative and maintain their customs in the face of changes brought about by increased contact with the outside world. As recently as 1985, some 85 percent of Rotumans voted against opening the island up to tourism, wary of the influence of Western tourists. P&O Cruises landed on the island twice in the 1980s.

Notable Rotumans and people of Rotuman descent[]

- Riamkau Sau: the last king of Rotuma

- Robin Everett Mitchell: president of the Association of National Olympic Committees; the Oceania National Olympic Committee; and “Olympic Solidarity.”

- Paul Manueli: former commander of the Royal Fiji Military Forces; Fiji cabinet minister; senator; successful businessman

- Jioji Konrote: president of Fiji (since 2015); former high commissioner to Australia

- Marieta Rigamoto: former Fiji information minister

- Daniel Fatiaki: Chief Justice of Fiji

- Seán Óg and Setanta Ó hAilpín (brothers of Rotuman descent): Irish sportsmen

- John Sutton: National Rugby League player

- Vilsoni Hereniko: playwright; film director

- Sapeta Taito: actress (The Land Has Eyes)

- Jono Gibbes (of Rotuman descent on his mother’s side): New Zealand rugby union player

- Rocky Khan (of Rotuman descent on his mother’s side): New Zealand Rugby Union player[11]

- Graham Dewes: Fiji Rugby Union player

- Daniel Rae Costello (of Rotuman descent): Fijian-born musician

- Rebecca Tavo (has a Rotuman father): Australian touch-rugby player[12]

- Selina Hornibrook (has a Rotuman mother): former Australian netball player

- Ngaire Fuata (has a Rotuman father): New Zealand television producer and singer[13]

- Pene Erenio: top Fiji soccer player (Savusavu)

- Ravai Fatiaki: Fiji Rugby Union player

- Sofia Tekela-Smith (raised on Rotuma by her grandmother): New Zealand artist

- David Eggleton (of Rotuman descent on his mother’s side): Poet Laureate of New Zealand

- Fred Fatiaki: coach

- Lee Roy Atalifo: Fiji Rugby Union player

Politics and society[]

In 1881, after Rotuma was ceded to the United Kingdom, it was governed as part of the Colony of Fiji, and a group of Rotuman chiefs travelled to London to meet Queen Victoria. The Queen bestowed the name of Albert on the paramount chief in honour of her husband, Prince Albert, who had died twenty years before.

Rotuma remained with Fiji after Fiji's independence in 1970 and the military coups of 1987.

Sociopolitical organization[]

Rotuma is divided into seven autonomous districts, each with its own chief (Gagaj ʻes Ituʻu), with villages:

- Noaʻtau (extreme southeast): Fekeioko, Maragteʻu, Fafʻiasina, Matuʻea, ʻUtʻutu, Kalvaka

- Oinafa (east): Oinafa, Lopta, Paptea

- Ituʻtiʻu (west, but east of western peninsula): Savlei, Lạu, Feavại, Tuạʻkoi, Motusa, Hapmak, Losa, Fapufa, Ahạu (Government Station)

- Malhaha (north): Pepheua, ʻElseʻe, ʻElsio

- Juju (south): Tuại, Haga, Juju

- Pepjei (southeast): ʻUjia, Uạnheta, Avave

- Ituʻmuta (western peninsula): Maftoa, Lopo

The district chiefs and elected district representatives make up the Rotuma Island Council. The districts are divided into subgroupings of households (hoʻaga) that function as work groups under the leadership of a subchief (gagaj ʻes hoʻaga). All district headmen and the majority of hoʻaga headmen are titled. In addition, some men hold titles without headship (as tög), although they are expected to exercise leadership roles in support of the district headman. Titles, which are held for life, belong to specified house sites (fuạg ri). All the descendants of previous occupants of a fuạg ri have a right to participate in the selection of successors to titles.

On formal occasions titled men and dignitaries such as ministers and priests, government officials, and distinguished visitors occupy a place of honor. They are ceremonially served food from special baskets and kava. In the daily routine of Village life, however, they are not especially privileged. As yet no significant class distinctions based on wealth or control of resources have emerged, but investments in elaborate housing and motor vehicles by a few families have led to visible differences in standard of living.

Political organization[]

At the time of arrival by Europeans there were three pan-Rotuman political positions: the fakpure, the , and the mua. The fakpure acted as convener and presiding officer over the council of district headmen and was responsible for appointing the sạu and ensuring that he was cared for properly. The fakpure was headman of the District that headed the alliance that had won the last war. The sạu's role was to take part in the ritual cycle, oriented toward ensuring prosperity, as an object of veneration. Early European visitors referred to the sạu as "king", but he actually had no secular power. The position of sạu was supposed to rotate between districts, and a breach of this custom was considered to be incitement to war. The role of mua is more obscure, but like the sạu, he was an active participant in the ritual cycle. According to some accounts the mua acted as a kind of high priest.

Following Christianization in the 1860s, the offices of sạu and mua were terminated. Colonial administration involved the appointment by the governor of Fiji of a Resident Commissioner (after 1935, a District Officer) to Rotuma. He was advised by a council composed of the district chiefs. In 1940 the council was expanded to include an elected representative from each district and the Assistant Medical Practitioner. Following Fiji's independence in 1970, the council assumed responsibility for the internal governance of Rotuma, with the District Officer assigned to an advisory role. Up until the first coup, Rotuma was represented in the Fiji legislature by a single senator.

Administratively, Rotuma is fully incorporated into Fiji, but with local government so tailored as to give the island a measure of autonomy greater than that enjoyed by other political subdivisions of Fiji. Rotuma has the status of a Dependency, and its administrative capital is in the district of Ituʻtiʻu, where the "tariạgsạu" (traditionally the name of the sạu's palace) meeting house for the Council of Rotuma is based.

At the national level, Fijian citizens of Rotuman descent elect one representative to the Fijian House of Representatives, and the Council of Rotuma nominates one representative to the Fijian Senate. Rotuma is also represented in the influential Great Council of Chiefs by three representatives chosen by the Council of Rotuma. For electoral purposes, Rotumans were formerly classified as Fijians, but when the Constitution was revised in 1997–1998, they were granted separate representation at their own request. (The majority of seats in Fiji's House of Representatives are allocated on a communal basis to Fiji's various ethnic groups) In addition, Rotuma forms part (along with Taveuni and the Lau Islands) of the Lau Taveuni Rotuma Open Constituency, one of 25 constituencies whose representatives are chosen by universal suffrage.

Social control[]

The hoʻaga, a kinship community, was the basic residential unit in pre-contact Rotuma.[14] The basis for social control is a strong socialization emphasis on social responsibility and a sensitivity to shaming. Gossip serves as a mechanism for sanctioning deviation, but the most powerful deterrent to antisocial behavior is an abiding belief in imminent justice, that supernatural forces (the ʻatua or spirits of ancestors) will punish wrongdoing. Rotumans are a rather gentle people; violence is extremely rare and serious crimes nearly nonexistent.

Conflict[]

Prior to cession, warfare, though conducted on a modest scale, was endemic in Rotuma. During the colonial era political rivalries were muted, since power was concentrated in the offices of Resident Commissioner and District Officer. Following Fiji's independence, however, interdistrict rivalries were again given expression, now in the form of political contention. Following the second coup, when Fiji left the Commonwealth of Nations, a segment of the Rotuman population, known as the "Mölmahao Clan" of Noaʻtau rejected the council's decision to remain with the newly declared republic. Arguing that Rotuma had been ceded to the United Kingdom and not to Fiji, these rebels declared in 1987 independence of Republic of Rotuma and were charged with sedition. It did not have any substantive support, majority opinion appears to favor remaining with Fiji, but rumblings of discontent remain.

See also[]

References[]

- Islands of Fiji, Island Directory, United Nations Environment Programme

- ^ "2017 Population and Housing Census - Release 1" (PDF). Fiji Bureau of Statistics. 2018-01-05. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-08-26. Retrieved 2019-08-26.

- ^ Rotuma Island | island, Fiji

- ^ http://permanent.access.gpo.gov/websites/pollux/pollux.nss.nima.mil/NAV_PUBS/SD/pub126/126sec03.pdf

- ^ http://www.rotuma.net/os/lajereports/LRI2007turtlereport.pdf

- ^ Ganilau, Bernadette Rounds (2007). Fiji Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (PDF). Convention on Biological Diversity. pp. 107–112. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- ^ "Klimatafel von Ahau / Insel Rotuma / Fidschi" (PDF). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world (in German). Deutscher Wetterdienst. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 September 2019. Retrieved 29 September 2019.

- ^ "BirdLife Data Zone: Rotuma". datazone.birdlife.org. Retrieved 3 June 2017.

- ^ "The Rotuman People", p. 4, in Teʻo Tuvale, An Account of Samoan History up to 1918

- ^ The History of Mankind by Professor Friedrich Ratzel, Book II, Section A, The Races of Oceania page 173, MacMillan and Co., Ltd., published 1896

- ^ Langdon, Robert (1984), Where the whalers went: an index to the Pacific ports and islands visited by American whalers (and some other ships) in the 19th century, Canberra, Pacific Manuscripts Bureau, p.209. ISBN 086784471X

- ^ Robson, Toby (30 January 2011). "Rocky Khan a sevens player with a difference". Fairfax Media. Retrieved 4 November 2013.

- ^ "Rotuman Sports".

- ^ "Ngaire Fuata | TAGATA PASIFIKA | TV ONE | TVNZ.co.nz".

- ^ Howard, Alan (1964). "Land Tenure and Social Change in Rotuma". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 73: 26–52.

- A.M. Hocart, Notes on Rotuman Grammar, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, London, 1919, 252.

External links[]

- Rotuma website - an exhaustive website on all things Rotuman by anthropologists Alan Howard and Jan Rensel

- The Land Has Eyes - an award-winning film set in Rotuma made by Rotumans.

- Rotuman Hafa - Rotuman dance (see also Tautoga)

- Amateur radio - Amateur radio operations from Rotuma, with information on Rotuman history, culture, flora, fauna, geography, etc.; lengthy bibliography.

- General information, energy supply

- The Vertebrates of Rotuma and Surrounding Waters, by George R. Zug, Victor G. Springer, Jeffrey T. Wiliams and G. David Johnson, Atoll Research Bulletin, No. 316

Coordinates: 12°30′S 177°4.8′E / 12.500°S 177.0800°E

- Rotuma

- Rotuma Group

- Geography of Polynesia

- Islands of Fiji

- Volcanoes of Fiji

- Shield volcanoes

- Divisions of Fiji

- States and territories established in 1881

- 1881 establishments in the British Empire

- Preliminary Register of Sites of National Significance in Fiji

- Important Bird Areas of Fiji