Tā moko

Tā moko is the permanent marking or "tattoo" as traditionally practised by Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand.

Tohunga-tā-moko (tattooists) were considered tapu, or inviolable and sacred.[1]

Background[]

Tattoo arts are common in the Eastern Polynesian homeland of the Māori people, and the traditional implements and methods employed were similar to those used in other parts of Polynesia.[2] In pre-European Māori culture, many if not most high-ranking persons received moko. Moko were associated with mana and high social status; however, some very high-status individuals were considered too tapu to acquire moko, and it was also not considered suitable for some tohunga to do so.[3] Receiving moko constituted an important milestone between childhood and adulthood, and was accompanied by many rites and rituals. Apart from signalling status and rank, another reason for the practice in traditional times was to make a person more attractive to the opposite sex. Men generally received moko on their faces, buttocks (raperape) and thighs (puhoro). Women usually wore moko on their lips (kauwae) and chins. Other parts of the body known to have moko include women's foreheads, buttocks, thighs, necks and backs and men's backs, stomachs, and calves. Initial European encounters with Pacific people’s tattooing resulted in the erroneous belief that it was once a European custom too, but was forgotten.[4]

Instruments used[]

Historically the skin was carved by uhi[5] (chisels), rather than punctured as in common contemporary tattooing; this left the skin with grooves rather than a smooth surface. Later needle tattooing was used, but in 2007 it was reported that the uhi was being used by some artists.[6]

Originally tohunga-tā-moko (moko specialists) used a range of uhi (chisels) made from albatross bone which were hafted onto a handle, and struck with a mallet.[7] The pigments were made from the awheto for the body colour, and ngarehu (burnt timbers) for the blacker face colour. The soot from burnt kauri gum was also mixed with fat to make pigment.[8] The pigment was stored in ornate vessels named oko, which were often buried when not in use. The oko were handed on to successive generations. A kōrere (feeding funnel) is believed to have been used to feed men whose mouths had become swollen from receiving tā moko.[9]

Men and women were both tā moko specialists and would travel to perform their art.[10]

Changes[]

The pākehā practice of collecting and trading mokomokai (tattooed heads) changed the dynamic of tā moko in the early colonial period. King (see below) talks about changes which evolved in the late 19th century when needles came to replace the uhi as the main tools. This was a quicker method, less prone to possible health risks, but the feel of the tā moko changed to smooth. Tā moko on men stopped around the 1860s in line with changing fashion and acceptance by pākehā.[citation needed]

Women continued receiving moko through the early 20th century,[11] and the historian Michael King in the early 1970s interviewing over 70 elderly women who would have been given the moko before the 1907 Tohunga Suppression Act.[12][13] Women were traditionally only tattooed on their lips, around the chin, and sometimes the nostrils.[14][15]

Tā moko today[]

Since 1990 there has been a resurgence in the practice of tā moko for both men and women, as a sign of cultural identity and a reflection of the general revival of the language and culture. Most tā moko applied today is done using a tattoo machine, but there has also been a revival of the use of uhi (chisels).[6] Women too have become more involved as practitioners, such as Christine Harvey of the Chathams, Henriata Nicholas in Rotorua and Julie Kipa in Whakatane. It is not the first time the contact with settlers has interfered with the tools of the trade: the earliest moko were engraved with bone and were replaced by metal supplied by the first visitors.[16] Most significantly was the adjustment of the themes and conquests the tattoos represented. Ta moko artist Turumakina Duley, in an interview for Artonview magazine, shares his view on the transformation of the practice: “The difference in tā moko today as compared to the nineteenth century is in the change of lifestyle, in the way we live. […] The tradition of moko was one of initiation, rites of passage - it started around that age - but it also benchmarks achievements in your life and gives you a goal to strive towards and achieve in your life.”[17] Duley got his first moko to celebrate his graduation from a Bachelor in Māori Studies.[17]

was established in 2000 "to preserve, enhance, and develop tā moko as a living art form".[18]

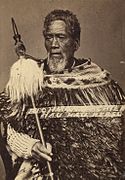

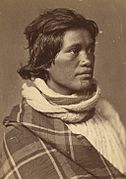

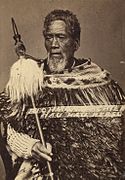

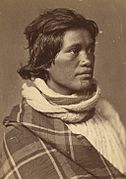

Māori moko from a 1908 publication

Tukukino Te Ahiātaewa

(Ngāti Tamaterā)

Te Aho-o-te-rangi Wharepu

(Ngāti Mahuta)

A large proportion of New Zealanders now have tattoos of some sort,[19] and there is "growing acceptance ...as a means of cultural and individual expression."[20]

In 2016 New Zealand politician Nanaia Mahuta had a moko kauae. When she became foreign minister in 2020, a writer said that her facial tattoo was inappropriate for a diplomat. There was much support for Mahuta, who said "there is an emerging awareness about the revitalisation of Māori culture and that facial moko is a positive aspect of that. We need to move away from moko being linked to gangs, because that is not what moko represent at all."[21]

Use by non-Māori[]

Europeans were aware of tā moko from at the time of the first voyage of James Cook, and early Māori visitors to Europe, such as Moehanga in 1805,[22] then Hongi Hika in 1820 and Te Pēhi Kupe in 1826,[23] all had full-face moko, as did several "Pākehā Māori" such as Barnet Burns. However, until relatively recently the art had little global impact.

Wearing of tā moko by non-Māori is named cultural appropriation,[24] and high-profile uses of Māori designs by Robbie Williams, Ben Harper and a 2007 Jean-Paul Gaultier fashion show were controversial.[25][26][27][28]

To reconcile the demand for Māori designs in a culturally sensitive way, the Te Uhi a Mataora group promotes the use of the term kirituhi,[29] which has now gained wide acceptance:[30][31][32][33]

...Kirituhi translates literally to mean—"drawn skin." As opposed to Moko which requires a process of consents, genealogy and historical information, Kirituhi is merely a design with a Maori flavour that can be applied anywhere, for any reason and on anyone...[29]

Gallery[]

- Tā moko

Riperata Kahutia (Te Aitanga-a-Mahaki)

Guide Susan

Tomika Te Mutu, (Ngāi Te Rangi)

Mrs. Rabone, 1871

Hariota Hull

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "The Māori - The Tattoo (Ta Moko)".

- ^ Hīroa 1951, p. 296

- ^ Higgins, Rawinia. "4. – Tā moko – Māori tattooing - Moko and status". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. New Zealand Ministry for Culture and Heritage. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ^ Pritchard, Stephen (2000-12-01). "Essence, Identity, Signature: Tattoos and Cultural Property". Social Semiotics. 10 (3): 331–346. doi:10.1080/10350330050136389. ISSN 1035-0330.

- ^ "Fig. 46.—Uhi, or chisels in the British Museum (actual size). Presented by Sir George Grey, K. C. B., &c". Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Revival of Moko". The New Zealand Herald. 28 December 2007.

- ^ Best, Eldson (1904). "The Uhi-Maori, or Native Tattooing Instruments". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 13 (3): 166–72.

- ^ "Kauri gum". Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Korere - Tasman District". Landcare Research - Manaaki Whenua. Retrieved 21 March 2014.

- ^ ELLIS, NGĀRINO (2014). ""KI TŌ RINGA KINGĀ RĀKAU Ā TE PĀKEHĀ?" DRAWINGS AND SIGNATURES OF "MOKO" BY MĀORI IN THE EARLY 19TH CENTURY". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 123 (1): 29–66. ISSN 0032-4000.

- ^ "A Relic of Barbarism". Wanganui Herald. 1904.

- ^ King, Michael (July 1973). "Moko". Te Ao Hou The Māori Magazine.

- ^ Smale, Aaron. "Ta Moko". New Zealand Geographic. Retrieved 4 May 2017.

- ^ "Is Permanent Makeup Worth It?". Pinky Cloud. Archived from the original on 5 August 2015. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ^ "History of Tattoos". TheTattooCollection.com. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ Higgins, Rawina (December 20, 2016). "Tā Moko Technology". Te Ara Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Ministry for Culture and Heritage Te Manatu Taonga. Retrieved January 9, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Crispin Howarth and Turumakina Duley. Maori Markings: tā moko. Other. Artonview, no. 98, Winter, 2019.

- ^ "Te Uhi a Mataora". Toi Māori Aotearoa. Toi Māori Aotearoa. Archived from the original on 7 April 2017. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ^ Mathewson, Nicole. "Employers more tolerant of hiring inked employees". Stuff. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Lake, Dan (10 June 2019). "Air New Zealand reverses ban on staff having tattoos". Newshub. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Ainge Roy, Eleanor (4 November 2020). "NZ website withdraws author's works after she criticises Māori foreign minister". The Guardian.

- ^ "...the first Maori who reached England...had a well tattooed face..."

- ^ "Fig. 10.—Tattooing on the face of Te Pehi Kupe, drawn by himself". Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Maori face tattoo: It is OK for a white woman to have one?". BBC. 23 May 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ^ Kassem, Mia (March 2003). "Contemporary Manifestations of the traditional Ta Moko". NZArtMonthly. Archived from the original on 2011-02-24.

- ^ "Cheeky French steal moko". Stuff. 13 September 2007. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ "Sharples: Protected Objects Third Reading Speech". Scoop. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

- ^ "Why Most People Shouldn't Get Ta Moko Maori Tattoos". About.com Style. Retrieved 2017-05-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Ta Moko - A History On Skin" (Press release). Christchurch Arts Festival 2005. 13 July 2005. Retrieved 3 May 2017 – via Scoop Independent News.

- ^ "Moko 'exploitation' causes concern". The New Zealand Herald. NZPA. 3 November 2003. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Ihaka, James (27 March 2009). "Ta Moko making its mark on Maori". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ "Myth and the moko". Waikato Times. Retrieved 16 November 2011.

- ^ Cheseman, Janelle (15 March 2014). "The resurrection of tā moko raises questions for Maori". Newswire. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

Sources[]

- Hīroa, Te Rangi (1951). The Coming of the Maori. Wellington: Whitcombe & Tombs.

- Jahnke, R. and H. T., "The politics of Māori image and design", Pukenga Korero (Raumati (Summer) 2003), vol. 7, no. 1, pp. 5–31.

- King, M., and Friedlander, M., (1992). Moko: Māori Tattooing in the 20th Century. (2nd ed.) Auckland: David Bateman. ISBN 1-86953-088-8

- Nikora, L. W., Rua, M., and Te Awekotuku, Ng., "Wearing Moko: Māori Facial Marking in Today's World", in Thomas, N., Cole, A., and Douglas, B. (eds.), Tattoo. Bodies, Art and Exchange in the Pacific and the West, London: Reacktion Books, pp. 191–204.

- Robley, Maj-Gen H. G., (1896). Moko, or Maori Tattooing. digital edition from New Zealand Electronic Text Centre

- Te Awekotuku, Ngahuia, "Tā Moko: Māori Tattoo", in Goldie, (1997) exhibition catalogue, Auckland: Auckland City Art Gallery and David Bateman, pp. 108–114.

- Te Awekotuku, Ngahuia, "More than Skin Deep", in Barkan, E. and Bush, R. (eds.), Claiming the Stone: Naming the Bones: Cultural Property and the Negotiation of National and Ethnic Identity (2002) Los Angeles: Getty Press, pp. 243–254.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Tā moko. |

- Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa Online Resources on Moko

- Images relating to moko from the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

- New Zealand Electronic Text Centre collection on Ta Moko, mokamokai, Horatio Robley and his art. A bibliography provides further links to other online resources.

- The rise of the Maori tribal tattoo, BBC News Magazine, 21 September 2012, Ngahuia Te Awekotuku, University of Waikato, New Zealand

- Māori art

- Māori culture

- Māori words and phrases

- Polynesian tattooing

- Tattoo designs