Mokomokai

Mokomokai, or Toi moko, are the preserved heads of Māori, the indigenous people of New Zealand, where the faces have been decorated by tā moko tattooing. They became valuable trade items during the Musket Wars of the early 19th century.

Moko[]

Moko facial tattoos were traditional in Māori culture until about the mid 19th century when their use began to disappear, although there has been something of a revival from the late 20th century. In pre-European Māori culture they denoted high social status. There were generally only men that had full facial moko, though high-ranked women often had moko on their lips and chins.[1]: 1 Moko tattoos served as identifying connection between an individual and their ancestors.[2]

Moko marked rites of passage for people of chiefly rank, as well as significant events in their lives. Each moko was unique and contained information about the person's rank, tribe, lineage, occupation and exploits. Moko were expensive to obtain and elaborate moko were usually limited to chiefs and high-ranked warriors. Moreover, the art of moko, the people who created and incised the designs, as well as the moko themselves, were surrounded by strict tapu and protocol.[1]: 1–3

Mokomokai[]

When someone with moko died, often the head would be preserved. The brain and eyes were removed, with all orifices sealed with flax fibre and gum. The head was then boiled or steamed in an oven before being smoked over an open fire and dried in the sun for several days. It was then treated with shark oil. Such preserved heads, mokomokai, would be kept by their families in ornately carved boxes and brought out only for sacred ceremonies.[3]

The heads of enemy chiefs killed in battle were also preserved; these mokomokai, being considered trophies of war, would be displayed on the marae and mocked. They were important in diplomatic negotiations between warring tribes, with the return and exchange of mokomokai being an essential precondition for peace.[1]: 3–4

Musket Wars[]

Trading for these heads with Western Colonisers, apparently, began with Sir Joseph Banks, the Botanist on HMB Endeavour, where he traded old linen drawers (underwear) for the head of a 14 year old boy.[4] It has since been suggested that this trade may have not been conducted voluntarily, as it is reported that Banks had a musket aimed at the leader of the Maori Tribe as he was reluctant to relinquish the head of his ancestor.[5] The head was traded as a "curio" and a fascination with the heads began to grow. This continued with Mokomokai heads being traded for muskets and the subsequent Musket Wars. During this period of social destabilisation, mokomokai became commercial trade items which could be sold as curios, artworks and as museum specimens which fetched high prices in Europe and America, and which could be bartered for firearms and ammunition.[1]: 4–5

The demand for firearms was such that tribes carried out raids on their neighbours to acquire more heads to trade for them. They also tattooed slaves and prisoners (though with meaningless motifs rather than genuine moko) in order to provide heads to order. The peak years of the trade in mokomokai were from 1820 to 1831. In 1831 the Governor of New South Wales issued a proclamation banning further trade in heads out of New Zealand, and during the 1830s the demand for firearms diminished because every surviving group was fully armed. By 1840 when the Treaty of Waitangi was signed, and New Zealand became a British colony, the export trade in mokomokai had virtually ended, along with a decline in the use of moko in Māori society, although occasional small-scale trade continued for several years.[1]: 5–6 [6]

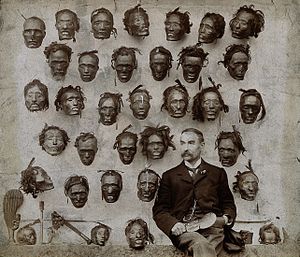

Robley collection[]

Major-General Horatio Gordon Robley was a British army officer and artist who served in New Zealand during the New Zealand Wars in the 1860s. He was interested in ethnology and fascinated by the art of tattooing as well as being a talented illustrator. He wrote the classic text on the subject of moko, Moko; or Maori Tattooing, which was published in 1896. After he returned to England he built up a notable collection of 35 to 40 mokomokai which he later offered to sell to the New Zealand Government. When the offer was declined, most of the collection was sold to the American Museum of Natural History.[7]

The collection was repatriated to Te Papa Tongarewa in 2014.[8]

Repatriation[]

More recently there has been a campaign to repatriate to New Zealand the hundreds of mokomokai held in museums and private collections around the world, either to be returned to their relatives or to the Museum of New Zealand for storage, though not display. It has had some success, though many mokomokai remain overseas and the campaign is ongoing.[7][9][10][11]

References[]

- ^ a b c d e Palmer, Christian; Tano, Mervyn L. (1 January 2004). Mokomokai: Commercialization and Desacralization (PDF). International Institute for Indigenous Resource Management. Retrieved 11 February 2021.

- ^ Cultural Heritage, Cultural Rights, Cultural Diversity: New Developments in International Law, edited by Silvia Borelli, Federico Lenzerini, page 163

- ^ NZETC: Mokomokai: Preserving the past Accessed 25 November 2008

- ^ Fennell, Marc; Stole, Monique Ross for Stuff the British (14 December 2020). "In 1770 Joseph Banks sparked a macabre trade that still haunts New Zealand today". ABC News. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ "The Headhunters". ABC Radio National. 13 November 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- ^ Janes, Robert R.; Conaty, Gerald T. (2005). Looking Reality In The Eye: Museums and Social Responsibility. University of Calgary Press. pp. 156–157. ISBN 978-1-55238-143-4.

- ^ a b "The trade in preserved Maori heads". The Sunday Star-Times. Archived from the original on 23 February 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ "Largest collection of ancestral remains in NZ history to be repatriated". Māori Television. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ^ Associated Press, Wellington. 7 April 2000. Aussie Museum to return Maori heads."Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 26 November 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ^ "Maori heads may return home". Reuters/One News. 6 November 2003. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ^ Associated Press, Paris. 4 January 2008. French city vows to return Maori head.[1]

Further reading[]

- Robley, H.G. (1896). Moko; Maori Tattooing. Chapman & Hall: London. Full text at the NZETC.

External links[]

- History of New Zealand

- Human trophy collecting

- Polynesian tattooing

- Māori art

- Māori words and phrases