Sandy Koufax

| Sandy Koufax | |||

|---|---|---|---|

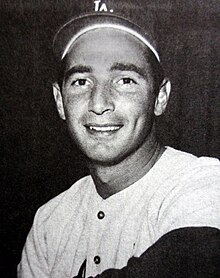

Koufax with the Los Angeles Dodgers, c. 1965 | |||

| Pitcher | |||

| Born: December 30, 1935 Brooklyn, New York | |||

| |||

| MLB debut | |||

| June 24, 1955, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |||

| Last MLB appearance | |||

| October 2, 1966, for the Los Angeles Dodgers | |||

| MLB statistics | |||

| Win–loss record | 165–87 | ||

| Earned run average | 2.76 | ||

| Strikeouts | 2,396 | ||

| Teams | |||

| |||

| Career highlights and awards | |||

| |||

| Member of the National | |||

| Induction | 1972 | ||

| Vote | 86.87% (first ballot) | ||

Sanford Koufax (/ˈkoʊfæks/; born Sanford Braun; December 30, 1935) is an American former professional baseball left-handed pitcher. He pitched 12 seasons for the Brooklyn/Los Angeles Dodgers of Major League Baseball (MLB) from 1955 to 1966. Koufax, at age 36 in 1972, became the youngest player ever elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He has been hailed as one of the greatest pitchers in baseball history.

Koufax's career peaked with a run of six outstanding years from 1961 to 1966, before arthritis in his left elbow ended his career prematurely at age 30. He was an All-Star for six seasons[1] and was the National League's Most Valuable Player in 1963. He won three Cy Young Awards in 1963, 1965, and 1966, by unanimous votes, making him the first three-time Cy Young winner in baseball history and the only one to win three times when one overall award was given for all of Major League Baseball instead of one award for each league. Koufax also won the NL Triple Crown for pitchers those same three years by leading the NL in wins, strikeouts, and earned run average.[2][3][4][5]

Koufax was the first major league pitcher to pitch four no-hitters and the eighth pitcher to pitch a perfect game in baseball history. Despite his comparatively short career, Koufax's 2,396 career strikeouts ranked 7th in history as of his retirement, at the time trailing only Warren Spahn (2,583) among left-handers. Koufax, Trevor Hoffman, Randy Johnson, Pedro Martínez, and Nolan Ryan are the only five pitchers elected to the Hall of Fame who had more strikeouts than innings pitched.

Koufax is also remembered as one of the outstanding Jewish athletes in American sports. His decision not to pitch Game 1 of the 1965 World Series because it fell on Yom Kippur garnered national attention as a conflict between religious calling and society, and remains a notable event in American Jewish history.[6][7]

Early life[]

Koufax was born in Brooklyn, New York, to a Jewish family and was raised in Borough Park.[8][9] His parents, Evelyn (née Lichtenstein) and Jack Braun, divorced when he was three years old. His mother was remarried when he was nine, to Irving Koufax.[10] Shortly after his mother's remarriage, the family moved to the Long Island suburb of Rockville Centre. Before tenth grade, Koufax's family moved back to the Bensonhurst section of Brooklyn.[11]

Koufax attended Brooklyn's Lafayette High School, where he was better known for basketball than for baseball. He started playing basketball for the Edith and Carl Marks Jewish Community House of Bensonhurst local community center team. Eventually, Lafayette had a basketball team; Koufax became team captain in his senior year, and ranked second in his division in scoring, with 165 points in 10 games.[9][12] In 1951, at the age of 15, Koufax also joined a local youth baseball league known as the "Ice Cream League". He started out as a left-handed catcher before moving to first base. While playing first base for Lafayette High School's baseball team with his friend Fred Wilpon,[13] he was spotted by Milt Laurie, a baseball coach who was the father of two Lafayette players. Laurie recognized that Koufax might be able to pitch, and recruited the 17-year-old Koufax to pitch for the Coney Island Sports League's Parkviews.[14]

Koufax attended the University of Cincinnati and was a walk-on on the freshman basketball team, a complete unknown to assistant coach Ed Jucker.[10] He later earned a partial scholarship. In spring 1954, he made the college baseball varsity team, which was coached by Jucker at that time.[15] In his only season, Koufax went 3–1 with a 2.81 earned run average, 51 strikeouts and 30 walks in 32 innings.[16][17] Bill Zinser, a scout for the Brooklyn Dodgers, sent the Dodgers front office a glowing report that apparently was filed and forgotten.[18]

After trying out with the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds,[19] Koufax did the same for the Pittsburgh Pirates at Forbes Field.[20] During his Pirates tryout, Koufax's fastball broke the thumb of Sam Narron, the team's bullpen coach. Branch Rickey, then the general manager of the Pirates, told his scout Clyde Sukeforth that Koufax had the "greatest arm [he had] ever seen".[21] The Pirates, however, failed to offer Koufax a contract until after he was already committed to the Dodgers.[22] Dodgers scout Al Campanis heard about Koufax from Jimmy Murphy, a part-time scout.[23] After seeing Koufax pitch for Lafayette, Campanis invited him to an Ebbets Field tryout. With Dodgers manager Walter Alston and scouting director Fresco Thompson watching, Campanis assumed the hitter's stance while Koufax started throwing. Campanis later said, "There are two times in my life the hair on my arms has stood up: The first time I saw the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel and the second time, I saw Sandy Koufax throw a fastball."[24] The Dodgers signed Koufax for a $6,000 ($58,000 today) salary, with a $14,000 ($135,000 today) signing bonus.[25] Koufax planned to use the money as tuition to finish his university education, if his baseball career failed.[26]

Professional career[]

Early years (1955–1960)[]

Because Koufax's signing bonus was greater than $4,000 ($39,000 today), he was known as a bonus baby. This forced the Dodgers to keep him on the major league roster for at least two years before he could be sent to the minors. To make room for him, the Dodgers optioned their future Hall of Fame manager, Tommy Lasorda, to the Montreal Royals of the International League. Lasorda would later joke that it took Koufax to keep him off the Dodger pitching staff.[27]

Koufax made his major league debut on June 24, 1955, against the Milwaukee Braves, with the Dodgers trailing 7–1 in the fifth inning. Johnny Logan, the first batter Koufax faced, hit a bloop single. Eddie Mathews bunted, and Koufax threw the ball into center field. He then walked Hank Aaron on four pitches to load the bases, but struck out Bobby Thomson on a 3–2 fastball—an outcome Koufax later came to view as "probably the worst thing that could have happened to me," leading, as it did, to five seasons spent "trying to get out of trouble by throwing harder and harder and harder."[28]

Koufax's first start was on July 6.[29] He lasted only 4+2⁄3 innings, giving up eight walks.[30] He did not start again for almost two months, but on August 27, Koufax threw a two-hit, 7–0 complete game shutout against the Cincinnati Reds for his first major league win.[30][31] Koufax threw 41+2⁄3 innings in 12 appearances that season, striking out 30 batters and walking 28. He had two wins in 1955, which were both shutouts.[32]

During the fall, he enrolled in the Columbia University School of General Studies, which offered night classes in architecture. The Dodgers won the 1955 World Series for the first title in franchise history, but Koufax did not appear in the series. After the final out of Game Seven, Koufax drove to Columbia to attend class.[33]

The year 1956 was not very different from 1955 for Koufax. Despite the blazing speed of his fastball, Koufax continued to struggle with his control.[34] He saw little work, pitching only 58+2⁄3 innings with a 4.91 earned run average, 29 walks and 30 strikeouts. When Koufax allowed baserunners, he was rarely permitted to finish the inning. Teammate Joe Pignatano said that as soon as Koufax threw a couple of balls in a row, Alston would signal for a replacement to start warming up in the bullpen. Jackie Robinson, in his final season, clashed with Alston on Koufax's usage. Robinson saw that Koufax was talented and had flashes of brilliance, and objected to Koufax being benched for weeks at a time.[35]

To prepare for the 1957 season, the Dodgers sent Koufax to Puerto Rico to play winter ball. On May 15, the restriction on sending Koufax down to the minors was lifted. Alston gave him a chance to justify his place on the major league roster by giving him the next day's start. Facing the Chicago Cubs at Wrigley Field, Koufax struck out 13 while pitching his first complete game in almost two years. For the first time in his career, he was in the starting rotation, but only for two weeks. Despite winning three of his next five with a 2.90 earned run average, Koufax did not get another start for 45 days. In that start, he struck out 11 in seven innings, but got a no-decision. On September 29, Koufax became the last man to pitch for the Brooklyn Dodgers before their move to Los Angeles, by throwing an inning of relief in the final game of the season.[36]

Over the next three seasons, Koufax was in and out of the Dodger starting rotation due to injuries. In 1958, he began 7–3, but sprained his ankle in a collision at first base, finishing the season at 11–11 and leading the NL in wild pitches. In June 1959, Koufax set the record for a night game with 16 strikeouts. On August 31, 1959, he surpassed his career-high with 18 strikeouts, setting the NL record and tying Bob Feller's major league record for strikeouts in one game.[37]

In 1959, the Dodgers won a close pennant race against the Braves and the Giants, then beat the Chicago White Sox in the World Series. Koufax pitched two perfect relief innings in the Series opener, though they came after the Dodgers were already behind 11–0. Alston gave him the start in the fifth game, at the Los Angeles Coliseum in front of 92,706 fans. Koufax allowed only one run in seven innings, but lost the 1–0 game when Nellie Fox scored on a double play. Returning to Chicago, the Dodgers won the sixth game and the Series.[38]

In early 1960, Koufax asked Dodgers general manager Buzzie Bavasi to trade him because he was not getting enough playing time. By the end of 1960, after going 8–13, Koufax was thinking about quitting baseball to devote himself to an electronics business that he had invested in. After the last game of the season, he threw his gloves and spikes into the trash. Nobe Kawano, the clubhouse supervisor, retrieved the equipment to return to Koufax the following year (or to somebody else if Koufax did not return to play).[39]

Domination (1961–1964)[]

1961 season[]

Koufax tried one more year of baseball and showed up for the 1961 season in better condition than he had in previous years. Years later he recalled, "That winter was when I really started working out. I started running more. I decided I was really going to find out how good I can be."[40] During spring training, Dodger scout Kenny Myers discovered a hitch in Koufax's windup: he would rear back so far that his vision was obstructed and he could not see the target.[41]

A day later, Koufax was pitching for the "B team" in Orlando. Teammate Ed Palmquist missed the flight, so Koufax was told he would need to pitch at least seven innings. In the first inning, Koufax walked the bases loaded on 12 straight pitches. Catcher Norm Sherry advised Koufax to throw slightly less hard in order to improve his control. The advice worked, as Koufax struck out the side, going on to pitch seven no-hit innings.[42]

It was the beginning of Koufax's breakout season. Posting an 18–13 record for the Dodgers in 1961, Koufax led the league with 269 strikeouts, breaking Christy Mathewson's 58-year-old NL mark of 267.[43] Koufax was selected as an All-Star for the first time and made two All-Star Game appearances; MLB held two All-Star games from 1959 through 1962.[44] He faced only one batter, in the ninth inning in the first game, giving up a hit to Al Kaline, and he pitched two scoreless innings in the second game.[45]

1962 season[]

In 1962, the Dodgers moved from the Los Angeles Coliseum, which had a 250-foot left-field line, to pitcher-friendly Dodger Stadium. The new park had a large foul territory and a comparatively poor hitting background. Koufax was an immediate beneficiary of the change, lowering his earned run average at home from 4.29 to 1.75.[46] On June 30 against the expansion New York Mets, Koufax threw his first no-hitter. In the first inning of that game, Koufax struck out all three batters on nine total pitches to become the sixth National League pitcher and the 11th pitcher in major league history to accomplish an immaculate inning. With the no-hitter, a 4–2 record, 73 strikeouts, and a 1.23 earned run average for June, he was given the Major League Baseball Player of the Month Award.[47][48] It would be the only time in his career he earned this distinction.[49]

Koufax had his strong season despite an injured pitching hand. While batting in April, Koufax had been jammed by a pitch from Earl Francis. A numbness developed in Koufax's index finger on his left hand, and the finger became cold and white. Koufax was pitching better than ever, however, so he ignored the problem, hoping that the condition would clear up. By July, though, his entire hand was becoming numb and he was unable to complete some games. In a start in Cincinnati, his finger split open after one inning. A vascular specialist determined that Koufax had a crushed artery in his palm. Ten days of experimental medicine successfully reopened the artery. Koufax finally was able to pitch again in September, when the team was locked in a tight pennant race with the Giants. But after the long layoff, Koufax was ineffective in three appearances as the Giants caught the Dodgers at the end of the regular season, forcing a three-game playoff.[50]

The night before the National League playoffs began, manager Alston asked Koufax if he could start the first game the next day. With an overworked pitching staff, there was no one else, as Don Drysdale and Johnny Podres had pitched the prior two days. Koufax obliged. Koufax later said, "I had nothing at all." He was knocked out in the second inning, after giving up home runs to future Hall of Famer Willie Mays and Jim Davenport. After winning the second game of the series, the Dodgers blew a 4–2 lead in the ninth inning of the deciding third game, losing the pennant.[51]

1963 season[]

In 1963, Major League Baseball expanded the strike zone.[52] Compared to the previous season, National League walks fell 13 percent, strikeouts increased six percent, the league batting average fell from .261 to .245, and runs scored declined 15 percent.[53] Koufax, who had reduced his walks allowed per nine innings to 3.4 in 1961 and 2.8 in 1962, reduced his walk rate further to 1.7 in 1963, which ranked fifth in the league.[2] The top pitchers of the era – Drysdale, Juan Marichal, Jim Bunning, Bob Gibson, Warren Spahn, and above all Koufax – significantly reduced the walks-given-up-to-batters-faced ratio for 1963, and subsequent years.[54]

On May 11, Koufax no-hit the San Francisco Giants 8–0, besting future Hall of Fame pitcher Marichal—himself a no-hit pitcher on June 15. Koufax carried a perfect game into the eighth inning against the powerful Giants lineup, including future Hall of Famers Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Orlando Cepeda. He walked Ed Bailey on a 3-and-2 pitch in the eighth, and pinch-hitter McCovey on four pitches in the ninth, before closing out the game.[55] As the Dodgers won the pennant, Koufax won the pitchers' Triple Crown, leading the league in wins (25), strikeouts (306) and earned run average (1.88).[56] Koufax threw 11 shutouts, setting a new post-1900 record for shutouts by a left-handed pitcher that stands to this day (the previous record of 10 shutouts had been held by Carl Hubbell for 30 years). Only Bob Gibson, a right-hander, has thrown more shutouts (13) since, and that was in 1968,[57] "the year of the pitcher."[58]

Koufax won the National League MVP Award and the Hickok Belt, and was the first-ever unanimous selection for the Cy Young Award.[59][60]

Facing the Yankees in the 1963 World Series, Koufax beat Whitey Ford 5–2 in Game 1 and struck out the first five batters and 15 overall, breaking Carl Erskine's decade-old record of 14 (Gibson would break Koufax's record by striking out 17 Detroit Tigers in the 1968 World Series opener). After seeing Koufax's Game 1 performance, Yogi Berra said, "I can see how he won 25 games. What I don't understand is how he lost five,"[61] to which Maury Wills responded, "He didn't. We lost them for him."[62] In Game 4, Koufax completed the Dodgers' series sweep with a 2–1 victory over Ford, clinching the Series MVP Award for his performance.[63][64]

1964 season[]

Koufax's 1964 season started with great expectations. On April 18, he struck out three batters on nine pitches in the third inning of a 3–0 loss to the Cincinnati Reds, becoming the only National League pitcher to have two nine-pitch/three-strikeout half-innings.[48] On April 22, however, "he felt something let go in his arm." Koufax ended up getting three cortisone shots for his sore elbow, and missed three starts.[65]

On June 4, playing at Connie Mack Stadium against the Phillies, Koufax walked Richie Allen on a very close full-count pitch in the fourth inning. Allen, who was thrown out trying to steal second, was the only Phillie to reach base that day. With his third no-hitter in three years, Koufax became only the second pitcher of the modern era (after Feller) to pitch three no-hitters.[66]

Koufax jammed his pitching arm in August while diving back to second base to beat a pick-off throw. He managed to pitch and win two more games. However, the morning after his 19th win, a shutout in which he struck out 13 batters, he could not straighten his arm. He was diagnosed by Dodgers' team physician Robert Kerlan with traumatic arthritis. With the Dodgers out of the pennant race, the book was closed on Koufax and his 19–5 record.[67]

Playing in pain (1965–66)[]

1965 season[]

The 1965 season brought more obstacles for Koufax. On March 31, the morning after pitching a complete spring training game, Koufax awoke to find that his entire left arm was black and blue from hemorrhaging. Koufax returned to Los Angeles to consult with Kerlan, who advised Koufax that he would be lucky to be able to pitch once a week. Kerlan also told Koufax that he would eventually lose full use of his arm. Koufax agreed not to throw at all between games—a resolution that lasted only one start. To get himself through the games he pitched in, Koufax resorted to Empirin with codeine for the pain, which he took every night and sometimes during the fifth inning. He also took Butazolidin for inflammation, applied capsaicin-based Capsolin ointment (called "atomic balm" by baseball players) before each game, and soaked his arm in a tub of ice afterwards.[68]

Despite the constant pain in his pitching elbow, Koufax pitched 335+2⁄3 innings and led the Dodgers to another pennant. He finished the year by winning his second pitchers' Triple Crown, leading the league in wins (26), earned run average (2.04) and strikeouts (382; the highest modern-day total at the time. Nolan Ryan struck out 383 batters in 1973). Koufax captured his second unanimous Cy Young Award. Koufax held batters to 5.79 hits per nine innings, and allowed the fewest base runners per 9 innings in any season ever: 7.83, breaking his own record (set two years earlier) of 7.96. Koufax had 11-game winning streaks in both 1964 and 1965.[2][69]

Perfection[]

On September 9, 1965, Koufax became the sixth pitcher of the modern era, and eighth overall, to throw a perfect game, the first by a left-hander since 1880.[70][71] The game was Koufax's fourth no-hitter,[71] setting a Major League record (subsequently broken by Ryan in 1981).[72] Koufax struck out 14 batters, at the time the most recorded in a perfect game (tied by Matt Cain in 2012). The game also featured a quality performance by the opposing pitcher, Bob Hendley of the Cubs. Hendley pitched a one-hitter and allowed only two batters to reach base.[73] Both pitchers had no-hitters intact until the seventh inning.[74]

This remains the only nine-inning major league game where the teams combined for just one hit.[75][76] The game's only run, scored by the Dodgers, was unearned. The Dodger run was scored without a hit when Lou Johnson walked, reached second on a sacrifice, stole third, and scored on an inaccurate throw by Chicago catcher Chris Krug.[74]

World Series and Yom Kippur[]

Koufax garnered headlines by declining to pitch Game 1 of the World Series because of his observance of the Jewish religious holiday of Yom Kippur. This decision garnered national attention as an example of conflict between professional pressures and personal religious beliefs.[6] Drysdale pitched the opener, but was hit hard by the Minnesota Twins.[77]

In Game 2, Koufax pitched six innings, giving up two runs, and the Twins won the Game 5–1 and took an early 2–0 lead in the series. The Dodgers fought back in Games 3 and 4, with wins by Claude Osteen and Drysdale. With the Series tied at 2–2, Koufax pitched a complete-game shutout in Game 5 for a 3–2 Dodgers lead as the Series returned to Minnesota's Metropolitan Stadium for Game 6. The Twins won Game 6 to force a seventh game. Starting Game 7 on just two days of rest, Koufax pitched through fatigue and arthritic pain. Despite giving up on his curveball early in the game after failing to throw strikes with it in the first two innings and pitching the rest of the game relying almost entirely on fastballs, Koufax threw a three-hit shutout to clinch the Series. The performance earned him his second World Series MVP award, making him the first player to win the award twice. Koufax also won the Hickok Belt a second time, the first time anyone had won the belt more than once. He was awarded Sports Illustrated magazine's Sportsman of the Year award.[2][60][78]

1966 season[]

Holdout[]

Before the 1966 season began, Koufax and Drysdale met separately with Dodger general manager Bavasi to negotiate their contracts for the upcoming year. After Koufax's meeting, he met Drysdale for dinner and complained that Bavasi was using Drysdale against him in the negotiations, asking, "How come you want that much when Drysdale only wants this much?"[79] Drysdale responded that Bavasi did the same thing with him, using Koufax against him. Drysdale's first wife, Ginger Drysdale, suggested that they negotiate together to get what they wanted. They demanded $1 million (equivalent to $8 million in 2020), divided equally over the next three years, or $167,000 (equivalent to $1.33 million in 2020) each for each of the next three seasons. Both players were represented by an entertainment lawyer, J. William Hayes, which was unusual during an era when players were not represented by agents.[80][81] At the time, Willie Mays was Major League Baseball's highest paid player at $125,000 (equivalent to $1 million in 2020) per year and multi-year contracts were very unusual.[82]

Koufax and Drysdale did not report to spring training in February. Instead, they both signed to appear in the movie Warning Shot, starring David Janssen. Drysdale was to play a TV commentator and Koufax a detective. Meanwhile, the Dodgers waged a public relations battle against them. After four weeks, Koufax gave Drysdale the go-ahead to negotiate new deals for both of them. Koufax ended up getting $125,000 and Drysdale $110,000 (equivalent to $0.88 million in 2020). They rejoined the team in the last week of spring training.[83] In April 1966, Kerlan told Koufax it was time to retire and that his arm could not take another season. Koufax kept Kerlan's advice to himself and went out every fourth day to pitch. He ended up pitching 323 innings, a 27–9 record, and a 1.73 earned run average. Since then, no left-hander has had more wins, nor a lower earned run average, in a season (Phillies pitcher Steve Carlton matched the 27-win mark in 1972). In the final game of the regular season, the Dodgers had to beat the Phillies to win the pennant. In the second game of a doubleheader, Koufax faced Bunning for the second time that season,[84] in a match-up between perfect game winners. Koufax, on two days rest, pitched a complete game, winning 6–3 to clinch the pennant.[85] He started 41 games (for the second year in a row); only two left-handers started more games in any season over the ensuing years through 2020.[86]

Season[]

The Dodgers went on to face the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series, and Game 2 marked Koufax's third start in eight days. He pitched well enough—Baltimore first baseman Boog Powell told Koufax's biographer, Jane Leavy, "He might have been hurtin' but he was bringin'"—but three errors by Dodger center fielder Willie Davis in the fifth inning produced three unearned runs. Baltimore's 20-year-old Jim Palmer pitched a four-hitter and the Orioles won 6–0.[87] Alston lifted Koufax at the end of the sixth inning,[87][88] with the idea of getting him extra rest before a potential fifth game. It never happened; the Dodgers were swept in four games, not scoring a single run in the last three.[89] Less than six weeks later, Koufax announced his retirement due to his arthritic condition on Friday, November 18, 1966.[90][91]

Career overall[]

In his 12-season career, Koufax had a 165–87 record with a 2.76 earned run average, 2,396 strikeouts, 137 complete games, and 40 shutouts. He was the first pitcher to average fewer than seven hits allowed per nine innings pitched in his career (6.79) and to strike out more than nine batters (9.28) per nine innings pitched in his career.[92] He also became the second pitcher in baseball history to have two games with 18 or more strikeouts, and the first to have eight games with 15 or more strikeouts. In his last ten seasons, from 1957 to 1966, batters hit .203 against Koufax, with a .271 on-base percentage and a .315 slugging average.[93]

Koufax's postseason record is impressive: a 4–3 won-lost record with a 0.95 earned run average, in four World Series. He is on the very short list of pitchers who retired with more career strikeouts than innings pitched. Koufax was selected as an All-Star for six consecutive seasons[1] and made seven out of eight All-Star Game appearances those seasons (he was not selected for the 2nd All-Star Game in 1962).[44] He pitched 6 innings in four All-Star games,[94] including being the starting pitcher for 3 innings in the 1966 All-Star Game.[95]

Koufax was the first pitcher to win multiple Cy Young Awards, as well as the first pitcher to win a Cy Young Award by a unanimous vote. He is also the only pitcher to win three Cy Young Awards in the era in which the award was presented to one pitcher across the board, rather than one in each major league, and one of three Dodgers pitchers to win the one-across-the-board Cy Young Award. (The others were Don Newcombe, the first Cy Young winner in 1956, and Drysdale in 1962.) Each of Koufax's three Cy Young Awards were by unanimous vote.[2][96] Koufax and Juan Marichal are the only two pitchers to have more than one 25-win season in the post-war era (1946–present), with each pitcher recording three.[97]

Pitching style[]

"I knew every pitch he was going to throw and still I couldn't hit him."[98]

—Willie Mays

Koufax threw with a pronounced straight-over-the-top arm action. This aided in his devastating curveball and may have increased his velocity, but reduced the lateral movement on his pitches, especially movement away from left-handed hitters. Most of his velocity came from his strong legs and back, combined with a high leg kick during his wind-up and long forward extension on his release point toward home plate. Throughout his career, Koufax relied heavily on two pitches.[99] His four-seam fastball gave batters the impression of rising as it approached them, due to back-spin.[100] It not only appeared to move very late but also might move on multiple planes. His overhand curveball, spun with the middle finger, dropped vertically 12 to 24 inches due to his arm action. Rob Neyer called it the best curve of all time.[101] He also occasionally threw a changeup and a forkball.[99]

At the beginning of his career, Koufax fought a tendency to "tip" pitches (that is, reveal which pitch was coming due to variations in his wind-up). Batters were able to gain a competitive advantage from the position he held his hands at the top of the wind-up: when throwing a fastball with baserunners, his hand position in the stretch would be higher than when he threw curveballs. Koufax attempted to counter this by adjusting his hand position to better hide upcoming deliveries.[102] Late in his career, his tendency to tip pitches became even more pronounced. Good hitters could often predict what pitch was coming, but were still unable to hit it. Willie Mays said "I knew every pitch he was going to throw -- fastball, breaking ball or whatever. Actually, he would let you look at it. And you still couldn't hit it."[103][104]

Post-playing career[]

In 1967, Koufax signed a 10-year contract with NBC for US$1 million (equivalent to $7.8 million in 2020) to be a broadcaster on the Saturday Game of the Week. He quit after six years, just prior to the start of the 1973 season.[105][106]

The Dodgers hired Koufax to be a minor league pitching coach in 1979. He resigned in 1990, saying he was not earning his keep, but most observers blamed it on his uneasy relationship with manager Tommy Lasorda.[107] Koufax returned to the Dodger organization in 2004 when the Dodgers were sold to Frank McCourt.[75][108] The Dodgers again hired Koufax in 2013 as a special advisor to team chairman Mark Walter to work with the pitchers during spring training and consult during the season.[109]

Legacy[]

In his first year of eligibility in 1972, Koufax was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, just weeks after his 36th birthday. His election made him the Hall's youngest member ever elected, five months younger than Lou Gehrig upon his election in 1939, though because the 1972 induction ceremony was nearly eight months after the election, Koufax's age at induction was slightly older than Gehrig's, making Gehrig the youngest player ever inducted.[111] On June 4 of that same year, Koufax's uniform number 32 was retired alongside those of Dodger greats Roy Campanella (39) and Jackie Robinson (42).[112]

In 1999, The Sporting News placed Koufax at number 26 on its list of "Baseball's 100 Greatest Players".[113] That same year, he was named as one of the 30 players on the Major League Baseball All-Century Team. Although he rarely makes public appearances, he went to Turner Field in Atlanta for the introduction ceremony before Game 2 of the 1999 World Series.[114]

In 1990 he was inducted into the Southern California Jewish Sports Hall of Fame.[115] Koufax was the final player chosen in the inaugural Israel Baseball League draft in April 2007. Koufax, 71, was picked by the Modi'in Miracle. "His selection is a tribute to the esteem with which he is held by everyone associated with this league", said Art Shamsky, who managed the Miracle. "It's been 41 years between starts for him. If he's rested and ready to take the mound again, we want him on our team." Koufax declined to join the Miracle.[116][117]

Before the 2015 MLB All-Star Game in Cincinnati, Koufax was introduced as one of the four best living players (as selected by the fans of major league baseball), along with Willie Mays, Hank Aaron and Johnny Bench. He threw the ceremonial first pitch to Bench from in front of the base of the mound.[118]

Koufax was included among a group of prominent Jewish Americans honored at a May 27, 2010, White House reception for Jewish American Heritage Month. During welcome remarks in a reminiscence of Koufax's decision not to play on the Jewish holy day of Yom Kippur, U.S. President Barack Obama said that the two had "something in common." Obama continued: "He can't pitch on Yom Kippur. I can't pitch."[119][120] Obama directly acknowledged the high esteem with which Koufax is held: "This is a ... pretty distinguished group," he said of the invited guests, which included members of the House and Senate, two justices of the Supreme Court, Olympic athletes, entrepreneurs, rabbinical scholars, "and Sandy Koufax." The mention of his name brought the biggest cheer at the event.[119]

Personal life[]

Koufax has been described by Sports Illustrated's John Rosengren as a "secular Jew".[121] Regardless, his decision to not pitch on Yom Kippur in 1965 was highly significant for Jewish citizens of the U.S.[121] Author Larry Ruttman called Koufax "an icon" for Jewish people, because of his pitching skill and what he calls Koufax's "deep respect for his Judaism", as shown in 1965.[122]

Koufax married Anne Widmark, daughter of actor Richard Widmark, in 1969; the couple divorced in 1982. His second marriage, to Kimberly Francis, a personal trainer, lasted from 1985 to 1998.[106] Neither marriage produced children.[106] His third wife is Jane Dee Purucker Clarke, born in 1949; a college sorority sister of future First Lady Laura Bush, Purucker Clarke has a daughter from her prior marriage, to artist John Clem Clarke.[123]

Koufax serves as a member of the advisory board of the Baseball Assistance Team, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization dedicated to helping former Major League, Minor League, and Negro league players through financial and medical difficulties.[124]

Career statistics[]

| W | L | ERA | G | GS | CG | SHO | SV | IP | H | R | ER | HR | BB | SO | HBP | WP | BF | WHIP | ERA+ | WAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 165 | 87 | 2.76 | 399 | 314 | 137 | 40 | 9 | 2,324.1 | 1,754 | 806 | 713 | 204 | 817 | 2,396 | 18 | 87 | 9,497 | 1.106 | 131 | 53.1 |

Quotes in popular culture[]

He is quoted by Jack Nicholson in the tragicomedy movie "One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest" (1975) when he comments on an imaginary baseball game while the television is switched off.[125]

He is also referenced by John Goodman in the crime comedy film "The Big Lebowski" (1998) describing the Jewish culture: “3,000 years of beautiful tradition from Moses to Sandy Koufax!“[126][127]

A reference is also made to him in the film "Identity Thief" (2013). The main character, Sandy Patterson (Jason Bateman) explains that his first name comes from the famous baseball player who, like his father, liked to hold his bat in one hand.[128][129]

He is mentioned in the film “Coupe de Ville” (1990). Marvin (Daniel Stern) watches Koufax pitching a game on television in a motel room. When his brothers, Bobby (Patrick Dempsey) and Buddy (Arye Gross) begin arguing, Marvin protests, pointing out that Koufax is pitching a shutout.[1]

Stephen King also quotes him in his novel and horror film "Needful Things" (published in 1991), where his 1956 baseball card from the Topps gets Brian Rusk, one of the young heroes, into trouble.[130]

The American Indie-Pop Band “Koufax” is named after him.[131][132]

See also[]

|

|

Notes[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sandy Koufax". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved December 19, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Sandy Koufax Statistics". www.baseball-reference.com. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ "1963 Major League Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on February 11, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ "1965 Major League Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on December 15, 2006. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ "1966 Major League Leaders". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on October 15, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Solomvits, Sandor. "Yom Kippur and Sandy Koufax". JewishSports.com. Archived from the original on October 18, 2006. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ "Sandy Koufax's refusal to pitch on Yom Kippur still resonates". ESPN.com. September 21, 2015. Retrieved April 11, 2021.

- ^ "Big League Jews". Jewish Sports Review. 12 (137): 19. January–February 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Brody, Seymour. "Koufax Biography". jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved November 15, 2006.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Koufax Biography". www.hickoksports.com. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved November 15, 2006.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 19–22.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 22–28; Leavy, pp. 37–40.

- ^ "Sandy Koufax could testify at trial". ESPN. Associated Press. March 13, 2012. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 32–39.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Leavy, p. 50.

- ^ Dyer, Mike (May 4, 2014). "Sandy Koufax's season with UC Bearcats remembered". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Retrieved June 20, 2016.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Gruver, p. 80.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 56–57.

- ^ Leavy, p. 54

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 70–74.

- ^ Baseball Anecdotes by Daniel Okrent and Steve Wulf, Harper and Row Publishers, 1989

- ^ Leavy, p. 55

- ^ Dalin, David G. (September 27, 2011). "Why we can't forget Sandy Koufax". CBS News. Retrieved January 12, 2017.

- ^ Kahn, p. 95.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 42, 75–94.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 95–97.

- ^ Biederman, Lester J. (May 16, 1966). "Koufax Recalls His Wild Start At Forbes Field". Pittsburgh Press. p. 35. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leavy, p. 74.

- ^ McNeil, p. 182.

- ^ Leavy, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 3, 105–107.

- ^ Faber (2010), p. 57

- ^ Leavy, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 117–124; Leavy, pp. 87–90.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 125–138; Leavy, pp. 90–92; "Box score and play by play". Retrosheet. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 139–141; "Box score and play by play". Retrosheet. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 142–147; Leavy, pp. 93–95.

- ^ Leavy, p. 101.

- ^ Leavy, p. 102.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 153–155; Leavy, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 157–159; Leavy, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donnelly, Patrick. "Midsummer Classics: Celebrating MLB's All-Star Game". Sportsdata. Archived from the original on January 1, 2016. Retrieved December 26, 2020.

all players who were named to the AL or NL roster were credited with one appearance per season.

- ^ "First game box score and play by play". Retrosheet. Retrieved February 17, 2007. "Second game box score and play by play". Retrosheet. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ James, p. 233; Koufax and Linn, pp. 127–128; Leavy, p. 116.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 167–169; Leavy, p. 119; "Player of the Month Award". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "9-Pitches, 9-Strikes, Side Retired". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ "Major League Baseball Players of the Month". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved December 6, 2016.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 165–176; Leavy, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 176–177; Neyer, pp. 111–118.

- ^ "The Strike Zone: A Chronological Examination of the Official Rules by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ "1962 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved June 20, 2010."1963 National League Team Statistics and Standings". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ^ "Baseball Encyclopedia of MLB Players". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 181–183; Leavy, pp. 122–123.

- ^ The Baseball Chronicle, p. 344.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Shutouts". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Gruver, p. 234.

- ^ "1963 National League Statistics and Awards". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b 2009 ESPN Sports Almanac, p. 528.

- ^ "Sandy Koufax Biography". ESPN SportsCentury. Retrieved May 24, 2005.

- ^ Ronald N. Neff, www.thornwalker.com (March 29, 2007). "Joe Sobran – My Other Sandy (ASCII version)". Sobran.com. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 184–216; Leavy, pp. 132–143; "World Series MVP Award". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ "1963 World Series box scores and play by play". Retrosheet. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Leavy, p. 150.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 219–221; Leavy, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 222–228; Leavy, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 228–239; Leavy, pp. 157–160.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 234–240; Leavy, p. 160; "Single-Season Leaders for Strikeouts". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Eagle, Ed (June 13, 2018). "All-time perfect games in MLB history". Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Clair, Michael (September 9, 2014). "On this day 49 years ago, Sandy Koufax threw a perfect game ... in one hour and 43 minutes". Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 31, 2018.

- ^ Coffey, Alex. "Domination in the Dome: Nolan Ryan Throws His Fifth No-Hitter". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved March 11, 2020.

- ^ Landers, Chris (July 19, 2017). "Every perfect game in Major League history, ranked". Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hummer, Steve (August 28, 2016). "Macon's Bob Hendley made history with Koufax". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Sandy Koufax". www.baseballlibrary.com. Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ Pace, Robert (October 20, 2016). "Sandy Koufax turns 80: The 8 most memorable performances of his HOF career". Fox Sports. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Rothenberg, Matt. "Sandy Koufax Responded to a Higher Calling on Yom Kippur in 1965". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved December 14, 2020.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, pp. 256–268; Leavy, pp. 169–195; "1965 World Series box scores and play by play". Retrosheet. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Leavy, p. 205

- ^ Leavy, pp. 200–207.

- ^ "Sic Transit Tradition". Time. April 8, 1966. Archived from the original on February 22, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ "Double Play". Time. Time, Inc. March 25, 1966. Archived from the original on April 20, 2010. Retrieved April 30, 2008.

- ^ Leavy, pp. 207–210.

- ^ "July 27 box score". Baseball-Reference.com. July 27, 1966. Retrieved January 31, 2011.

- ^ Leavy, pp. 222–236.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Games Started". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Baltimore makes it two straight as Dodgers defense comes apart". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. October 7, 1966. p. 18.

- ^ "Box score and play by play". Retrosheet. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ "It's Baltimore in four straight". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. October 10, 1966. p. 8.

- ^ Leavy, pp. 236–239

- ^ Myers, Bob (November 19, 1966). "Elbow too much – Sandy Koufax quitting baseball". Spokesman-Review. (Spokane, Washington). Associated Press. p. 10.

- ^ "No Hitter Records". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved February 17, 2007. "Progressive Leaders for Hits Allowed/9IP". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007. "Progressive Leaders for Strikeouts/9IP". Baseball-Reference. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved February 17, 2007.

- ^ The play-by-play data from which these averages were calculated are available starting in 1957. See "Career Leaders & Records for Earned Run Average". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved January 16, 2013.

- ^ Horvitz and Horvitz, p. 97.

- ^ "Memories: 1966 All-Star Game a hot one". Winston-Salem Journal. July 15, 2009. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- ^ "MVP and Cy Young Awards". www.baseball-reference.com. Retrieved February 14, 2007.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Wins". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ Koufax and Linn, p. 153; Leavy, p. 24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Neyer & James (2004), pp. 270–271; Leavy, pp. 6–15.

- ^ Leavy, pp. 7–8, 79.

- ^ Neyer & James (2004), p. 34

- ^ Orfalea, Gregory (October 6, 2016). "The Incomparable Career of Sandy Koufax". The Atlantic. Retrieved December 7, 2020.

- ^ "ESPN Classic - Koufax's dominance was short but sweet". www.espn.com. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ Gruver, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Leavy, p. 251.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Schwartz, Larry. "ESPN Classic – Koufax dominating in '65 Series". espn.com. Retrieved February 18, 2007.

- ^ Leavy, pp. 255–258.

- ^ "Koufax returns to Dodgertown". Addict Baseball and Football Forum. Archived from the original on December 28, 2004. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ "Dodgers to be joined by Koufax at Spring Training". Los Angeles Dodgers.

- ^ "Dodgers' all-time retired numbers". Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Retired Numbers – Kirby Puckett". minnesota.twins.mlb.com. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved August 21, 2021.

- ^ "Dodgers Retired Numbers". MLB.com. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ "The Sporting News Selects Baseball's 100 Greatest Players". The Sporting News. 223 (17): 16. April 26, 1999. Archived from the original on April 16, 2005.

- ^ "The All-Century Team". mlb.mlb.com. Retrieved February 15, 2007. "Koufax makes appearance at World Series". CNN/SI. October 24, 1999. Archived from the original on October 6, 2008. Retrieved February 15, 2007.

- ^ "Sandy Koufax". Southern California Jewish Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ "Baseball Toaster: Humbug Journal : He'll be working on 14,875 days rest". Humbug.baseballtoaster.com. April 24, 2007. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Lloyd de Vries (April 27, 2007). "Koufax Drafted By Israeli Baseball Team". CBS News. Retrieved August 30, 2009.

- ^ Snyder, Matt (July 14, 2015). "Koufax, Mays, Aaron, Bench voted by fans as four greatest living players". CBS Sports. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Knoller, Mark (May 28, 2010). "Obama Honors Jewish Americans at White House Reception, May 27, 2010". Cbsnews.com. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ "Remarks by the President at Reception in Honor of Jewish American Heritage Month". Obama White House Archive. May 27, 2010. Retrieved September 2, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosengren, John (September 23, 2015). "Myth and fact part of legacy from Sandy Koufax's Yom Kippur choice". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved December 20, 2020.

- ^ Ruttman, "Sandy Koufax: Pitcher Nonpareil and Perfect Gentleman".

- ^ https://fabwags.com/sandy-koufaxs-wife-jane-purucker-clarke/

- ^ "B.A.T. honors Steinbrenner, Clemens at 15th annual dinner" (Press release). Major League Baseball. Retrieved December 1, 2020.

- ^ "Thoughts watching One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest". Andy B Sports. January 31, 2016. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Sales, Ben (May 5, 2020). "'The Big Lebowski' is a perfect watch for our crazy times. It's also surprisingly Jewish". Washington Jewish Week. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "3,000 Years of Beautiful Tradition from Moses to Sandy Koufax". Author Mark Yost. January 24, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Roeper, Richard. "Identity Thief movie review & film summary (2013) | Roger Ebert". rogerebert.com. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ Identity Thief (2013) - IMDb, retrieved June 20, 2021

- ^ Gray, Richard (November 8, 2019). "Inconstant Reader: Needful Things". The Reel Bits. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "Koufax | Biography & History". AllMusic. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

- ^ "Koufax". www1.wdr.de (in German). December 7, 2015. Retrieved June 20, 2021.

References[]

- 2009 ESPN Sports Almanac. New York: ESPN Books. 2008. ISBN 978-0-345-51172-0.

- Faber, Charles F. (2010). Major League Careers Cut Short: Leading Players Gone by 30. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. ISBN 978-0786462094.

- Gruver, Edward (2000). Koufax. Taylor Trade Publishing. ISBN 0-87833-157-3.

- Horvitz, Peter S.; Horvitz, Joachim (2001). The Big Book of Jewish Baseball. New York: S.P.I. Books. ISBN 1-56171-973-0.

- James, Bill (1988). The Bill James Baseball Abstract 1988. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35171-1.

- Kahn, Roger (2014). Rickey & Robinson: The True, Untold Story of the Integration of Baseball. New York: Rodale, Inc. ISBN 978-1-62336-297-3.

- Koufax, Sandy; Linn, Ed (1966). Koufax. New York: Viking Press.

- Leavy, Jane (2002). Sandy Koufax: A Lefty's Legacy. Perennial. ISBN 0-06-019533-9.

- McNeil, William F. (2001). The Dodgers Encyclopedia. Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc. ISBN 1-58261-316-8.

- Neyer, Rob (2006). Rob Neyer's Big Book of Baseball Blunders: A Complete Guide to the Worst Decisions and Stupidest Moments in Baseball History. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-8491-2.

- Neyer, Rob; James, Bill (2004). The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-6158-5.

- Pietrusza, David; Silverman, Matthew & Gershman, Michael, ed. (2000). Baseball: The Biographical Encyclopedia. Total/Sports Illustrated. ISBN 978-0-6812-0016-6.

- Ruttman, Larry. "Sandy Koufax: Pitcher Nonpareil and Perfect Gentleman". In American Jews and America's Game: Voices of a Growing Legacy in Baseball, University of Nebraska Press, 2013, ISBN 978-0-8032-6475-5

- The Baseball Chronicle: Year-By-Year History of Major League Baseball. Lincolnwood, Illinois: Publications International, Ltd. 2001. ISBN 978-0-7853-5803-9.

- "Sandy Koufax Biography". Baseball Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on February 20, 2008. Retrieved June 21, 2008.

- "Sandy Koufax Career Statistics". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved May 24, 2005.

- "Sandy Koufax Biography". ESPN SportsCentury. Retrieved May 24, 2005.

Further reading[]

- Verducci, Tom. "The Left Arm of God". Sports Illustrated. July 12, 1999.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sandy Koufax. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sandy Koufax |

- Sandy Koufax at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics and player information from MLB, or ESPN, or Baseball-Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball-Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Sandy Koufax at SABR (Baseball BioProject)

- Sandy Koufax at IMDb

- Biography and career highlights Baseball Library

- A Pair of Tefillin for Sandy Koufax – article from Chabad.org about the impact of Koufax's decision not to pitch on Yom Kippur on the Jewish community

| showAwards and achievements |

|---|

- 1935 births

- American male television actors

- Baseball players from New York (state)

- Basketball players from New York City

- Brooklyn Dodgers players

- Cincinnati Bearcats baseball players

- Cincinnati Bearcats men's basketball players

- Columbia University School of General Studies alumni

- Cy Young Award winners

- International Jewish Sports Hall of Fame inductees

- Jewish American baseball players

- Jewish Major League Baseball players

- Living people

- Los Angeles Dodgers executives

- Los Angeles Dodgers players

- Major League Baseball broadcasters

- Major League Baseball pitchers who have pitched a perfect game

- Major League Baseball pitchers

- Major League Baseball players with retired numbers

- World Series Most Valuable Player Award winners

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- National League All-Stars

- National League ERA champions

- National League Most Valuable Player Award winners

- National League Pitching Triple Crown winners

- National League strikeout champions

- National League wins champions

- People from Hidden Hills, California

- Sportspeople from Brooklyn

- People from Borough Park, Brooklyn

- People from Vero Beach, Florida

- Lafayette High School (New York City) alumni

- American men's basketball players

- People from Rockville Centre, New York

- People from Bensonhurst, Brooklyn