Santa Monica Airport

Santa Monica Airport Santa Monica Municipal Airport Clover Field | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

2006 USGS airphoto | |||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||

| Owner | City of Santa Monica | ||||||||||

| Operator | Santa Monica Airport Commission | ||||||||||

| Serves | Southern California | ||||||||||

| Location | Santa Monica and Mar Vista, Los Angeles, California, U.S. | ||||||||||

| Opened | 15 April 1923[1] | ||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 177 ft / 53.9 m | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 34°00′57″N 118°27′05″W / 34.01583°N 118.45139°WCoordinates: 34°00′57″N 118°27′05″W / 34.01583°N 118.45139°W | ||||||||||

| Website | Official website | ||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||

KSMO Location of Santa Monica Airport | |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Helipads | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Source: Federal Aviation Administration,[2] | |||||||||||

Santa Monica Airport (IATA: SMO, ICAO: KSMO, FAA LID: SMO) (Santa Monica Municipal Airport) is a general aviation airport largely in Santa Monica, California, United States. The airport is about 2 miles (3 km) from the Pacific Ocean (Santa Monica Bay) and 6 miles (10 km) north of Los Angeles International Airport. The FAA's National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems for 2009–2013 categorized it as a reliever airport.[3] The airport is scheduled to remain open until 2028.[4] Santa Monica Airport covers a total of 215 acres (87 ha) of land.[2]

One of the airport's former hangars, the Barker Hangar, is in use as a public events venue, and is commonly used for a number of televised awards ceremonies and concerts. It is also currently being used as a small-scale supermarket set for the current version of Supermarket Sweep.[5]

History[]

Early history[]

Originally Clover Field, after World War I aviator 2nd lieutenant Greayer "Grubby" Clover, the airport was the home of the Douglas Aircraft company.[6][7][8]

The first circumnavigation of the world by air, accomplished by the U.S. Army in a fleet of special custom built aircraft named the Douglas World Cruiser, took off from Clover Field on St. Patrick's Day, March 17, 1924, and returned there after some 28,000 miles (45,000 km).[9]:13

Cloverfield Boulevard — which confuses the field's naming for a crop of green rather than a fallen soldier — is a remnant of the airport's original name, as is the name of the Cloverfield film series, which derives its name from that road.[10]

World War II[]

Clover Field was once the site of the Army's 40th Division Aviation, 115th Observation Squadron and became a Distribution Center after World War II. Douglas Aircraft Company was headquartered adjacent to Clover Field. Among other important aircraft built there, Douglas manufactured the entire Douglas Commercial "DC" series of reciprocating-engine-powered airliners including the DC-1 (a prototype), DC-2, DC-3, DC-4, DC-5 (only 12 built), DC-6 and DC-7. During World War II, B-18 Bolo and B-18A bombers and thousands of C-47 (military version of the DC-3) and C-54 (later the civilian DC-4) military transports were built at Santa Monica, during which time the airport area was cleverly disguised from the air with the construction of a false "town" (built with the help of Hollywood craftsmen) suspended atop it.[11]

Post-World War II[]

In 1958, Donald Douglas asked the city to lengthen the airport's runway so that Douglas Aircraft could produce and test the DC-8 there. The city, bowing to objections of residents, refused to do so, and Douglas closed a plant that had employed 44,000 workers in World War II, moving airliner production to Long Beach Airport.[12]

Operations[]

The airport has a control tower. On average, it handled 296 operations a day (for the 12 months – ended July 2011.[13] Traffic decreased to 83,381 annual operations in 2014.[14]

As the Santa Monica Airport is one of many general aviation airports in the nation that is surrounded on some sides by residential development, the City of Santa Monica aggressively enforces one of the most stringent noise ordinances in the nation. In addition to responding to the community's noise concerns and enforcing the City's Aircraft Noise Ordinance, which includes a maximum allowable noise level, curfew hours and certain operational limitations, airport staff is involved in a variety of supplementary activities intended to reduce the overall impact of aircraft operations on the residential areas surrounding the airport. The following procedures and limitations are enforced in accordance with the noise ordinance. Violations may result in the imposition of fines and/or exclusion from Santa Monica Airport.

- Maximum Noise Level – A maximum noise level of 95.0 dBA Single Event Noise Exposure Level, measured at noise monitor sites 1,500 feet from each end of the runway, is enforced 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. There are no additional noise monitoring stations along the flight pattern, which is routed entirely over residential neighborhoods.

- Night Departure Curfew – No takeoffs or engine starts are permitted between 11 pm and 7 am Monday through Friday, or until 8 am on weekends. Exceptions are allowed for bona fide medical or public safety emergencies only.

- Operational Limitations – Touch-and-go, stop-and-go, and low approaches are prohibited on weekends, holidays, and weekdays from one half-hour after sunset until 7 am the following day.

In addition, there are numerous recommended noise abatement procedures and limitations that have been incorporated into the airport's Fly Neighborly Program and included in the program's outreach materials.

The aviation aspects of aircraft operations at the Santa Monica Airport and use of the nation's airspace is regulated by the federal government through the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). The City is jurisdictionally preempted by federal law from establishing or enforcing new local laws that would affect aircraft operations or the use of airspace around the Santa Monica Airport.[citation needed]

Typhoon is the only restaurant on the airport property with a runway view. Spitfire Grill is across, on Airport Avenue. The restaurant The Hump was closed in 2010 after its chef and owner were arrested for serving whale meat.[15]

The Museum of Flying at the airport houses a collection of historic aircraft. A new facility was built on the south side of the airport and is now open.

One of the airport's oldest buildings, next to the restored Douglas DC-3, hosts the U.S. Civil Air Patrol's Clover Field Composite Squadron 51.

Landing fees[]

On August 1, 2005, the Santa Monica City Council implemented a revised landing fee program (Resolution No. 9855) for all transient aircraft (those not based at the Santa Monica Airport) based on a uniform rate of $2.07 per 1000 pounds of maximum certificated gross landing weight. Since the Santa Monica Airport receives no federal, state or local funding to operate, the landing fees fill the gap between other airport revenue and the cost of operations.[16]

On April 13, 2013 the rates were approved for increase to $5.48 per 1,000 pounds of maximum certificated gross landing weight.[citation needed]

Airport Park[]

Airport Park opened as an 8.3-acre (3.4 ha) public park on recaptured aviation lands at the southeast corner of the airport. The park[17] features a synthetic turf soccer field, open green space and off-leash dog area.

Barker Hangar[]

The airport also includes Barker Hangar, a 35,000 foot entertainment venue.[18] The hangar hosts a variety of events, including boxing matches, art presentations, movies, concerts, wine and food festivals, and trade shows.[19][20][21][22]

Future[]

The city has invited the public to offer input regarding the airport's future.[23] The city of Santa Monica sued the federal government seeking to void a 1948 agreement in which the city agreed to keep the land for aviation use in perpetuity in exchange for title to the property.[24] On February 13, 2014, Judge John F. Walter dismissed the lawsuit, ruling that the city's "quiet title action" was barred by the statute of limitations and that the other issues would not be ripe for a judicial decision until the city decides definitively whether it will close the airport.[25]

The city appealed on October 14, 2014, citing the expiration of the 1984 agreement, after which FAA had agreed to release control of the city-owned parcel. The appeal also noted that the FAA's leasehold, granted during World War II, was for that purpose alone, and could not be transformed into a larger interest (such as a permanent taking of city land by FAA demanding use of the land for air-travel purposes in perpetuity).[26] There has yet been no finally conclusive legal decision, nor any preclusive agreement reached between the city and the aviation interests/FAA. An array of issues exists, which are still hotly debated in local, state, and national political arenas – as well as the courts.

The consensus opinion is that the many issues will ultimately be decided in the courts, with the dates of transfer-of-control being the central issues. In November 2014, voters passed the city-council-sponsored Measure LC, with a 60% "yes" vote. Measure LC places limitations on land use once the airport is closed. It proscribes commercial development, limiting development of the land to "public parks, recreational facilities or open space."[27] However, it allows the city council to decide what constitutes such facilities and to replace existing structures without voter approval.

Cited reasons for public support of airport closure are an alleged threat to safety, despite no ground fatalities in the neighborhood around the airport in over a century,[28] including a November 26, 1993 crash by a student pilot into an apartment building directly adjacent to a gasoline filling station, in a densely populated area of the city, and resulting in three fatalities (none on the ground).[28]

The western parcel of the land on which the airport sits was to revert to city control, on June 15, 2015, of this sub-parcel of the city-owned land, by expiry of prior city-FAA agreements.[29] One tactic recommended by airport opponents is to demolish the portion of the runway which sits upon this land, with the primary justification being safety. That is, at a minimum, the allowance of a buffer between the end of the runway and residential houses – currently 300 feet away – more preferably with the installation of aircraft-arrestors to prevent any runway overshoot from rolling past the runway and into the residential homes. The FAA offered such an arrestor system to the city in 2008, but this offer was rebuffed.[30]

On January 28, 2017, it was announced that Santa Monica city officials and the Federal Aviation Administration had reached an agreement to close the Santa Monica Airport on December 31, 2028 and return 227 acres of aviation land to the city for eventual redevelopment. It is anticipated that the airport land will be redeveloped into areas for parks, open space, recreation, education and/or cultural use.[31]

In an attempt to reduce jet traffic, the city planned to shorten the runway from 4,973 feet to 3,500 feet by repainting the runway and moving some navigational aids.[32][33] The runway shortening was completed on December 23, 2017.[34]

Accidents[]

- On Labor Day weekend in 1989, a P-51 Mustang crashed into a home on Wade Street near Brooklake Street in Mar Vista. The pilot and passenger were both injured.[35] During take-off, a piston rod broke, causing complete and sudden loss of power. The pilot, Robert E. Guilford, opted to try a return to the airport rather than ditch in the ocean as it was full of Labor Day beachgoers. The P-51 crashed into the house and then onto the street, spilling aviation fuel but never catching on fire.

- In 1994, the pilot of a single-engine Piper Saratoga died when a fuel system misconfiguration led to an in-flight engine shutdown. The aircraft stalled in a subsequent 180 degree turn for a forced emergency landing and struck the ground, which resulted in a post-crash fire.[36]

- On March 28, 2001, an inexperienced pilot rented a Cessna 172 at the airport and subsequently lost control of the aircraft over the Pacific Ocean upon encountering dark, instrument meteorological conditions. Three were killed.[37]

- On November 13, 2001, the pilot of a twin-engine Cessna failed to remove the gust locks prior to startup and two were killed when the aircraft overran the runway after an unsuccessful aborted takeoff.[38]

- On March 13, 2006, game-show host Peter Tomarken and his wife Kathleen died when his Beechcraft Bonanza crashed during climb-out from the airport. The aircraft had engine trouble and attempted to turn back before crashing into Santa Monica Bay.[39][40]

- On January 13, 2008, a home-built aircraft ran off the end of runway 21 after a brake failure, jumped over the hillside, landing on a service road. The three passengers on board were not hurt, although the kit-built aircraft was damaged severely. The runway was closed for 20 minutes.

- On January 28, 2009, a single-engine SIAI-Marchetti SF.260 lost power following takeoff and attempted to return to the airport. The aircraft struck the ground on the north side of runway 21 and caught fire, killing pilot Paulo Emanuele, general manager of Airliners.net, and passenger Martin Schaedel, an Internet entrepreneur. Investigators determined a probable cause was the pilot's failure to select the proper fuel tank for takeoff, which resulted in a loss of engine power.[41][42]

- On August 2, 2009, a Rutan Long-EZ experienced engine failure after takeoff. The pilot attempted to turn back to the runway, but crashed on the taxiway in the process of landing. The pilot, flying alone, was severely injured and the airplane was destroyed.[43]

- On July 1, 2010, a Cessna 152, crashed into the Penmar Golf Course shortly after take-off. The pilot was killed.[44]

- On August 29, 2011, a student pilot operating a small plane crashed into a home at 21st Street and Navy Street after take-off.[45] The pilot was soloing and encountered a problem with his airspeed indicator and returned but used too much runway for a safe landing. Having been instructed by the tower to perform a go-around, the pilot obliged but stalled the aircraft into a residence. The pilot was seriously injured and two of the three painters performing work on the home suffered minor injuries. The aircraft was totalled.[46][47]

- On September 29, 2013, a twin-engine Cessna Citation business jet that had just landed veered off the runway and crashed into a hangar, causing the hangar to collapse and setting fire to several other hangars.[48] The pilot and his adult son were both killed.[49]

- On March 5, 2015, actor Harrison Ford's 1942 Ryan PT-22 Recruit began having engine trouble at 2:25 pm right after take-off from Santa Monica Airport and attempted a 180 degree turn to return to field. The aircraft did not have sufficient airspeed and altitude to complete the emergency maneuver and was forced to make an emergency landing on the Penmar Golf Course a few hundred meters from the runway. Ford was attended at the crash scene by a spine surgeon who was practicing at the golf course and assisted in extricating Ford from the aircraft in case it caught fire.[50][51][52][53][54][55]

See also[]

- California World War II Army Airfields

- J.C. Barthel, who planned to establish "an aerial passenger service," 1922

- Santa Monica Army Air Forces Redistribution Center

- California during World War II

References[]

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Air Force Historical Research Agency website http://www.afhra.af.mil/.

- ^ Santa Monica Airport History

- ^ Jump up to: a b FAA Airport Form 5010 for SMO PDF, effective October 8, 2020.

- ^ National Plan of Integrated Airport Systems (NPIAS): 2009–2013 (PDF), Federal Aviation Administration, retrieved March 31, 2017

- ^ Dan Weikel and Dakota Smith (January 28, 2017). "Santa Monica Airport will close in 2028 and be replaced by a park, officials say". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ First Supermarket Sweep footage showcases fun-filled grocery store race for $100k. Entertainment Weekly (August 31, 2020). Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Richard E. Osbourne. "Clover Field". The California State Military Museum. California State Military Department. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

- ^ Cecilia Rasmussen (May 29, 2005). "Windows Shed Light on High School's Sacrifice". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 20, 2012.

Along with his name inscribed in the window, Lt. Greayer "Grubby" Clover, a World War I pilot, is also the namesake of Santa Monica Airport's Clover Field.

- ^ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, p. 15, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906- 0-4.

- ^ Thomas, Lowell (1925). The First World Flight. Boston & New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- ^ Kevin P. Sullivan (March 11, 2016). "What is Cloverfield? A brief explanation". Entertainment Weekly. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved March 8, 2020.

- ^ Parker, Dana T. Building Victory: Aircraft Manufacturing in the Los Angeles Area in World War II, pp. 13-24, Cypress, CA, 2013. ISBN 978-0-9897906- 0-4.

- ^ Garvey, William, Battled field, Aviation Week and Space Technology, February 24, 2014, p.18

- ^ FAA's Air Traffic Activity System website

- ^ http://aspm.faa.gov/opsnet/sys/Airport.asp

- ^ http://www.seashepherd.org/news-and-media/2011/05/23/sea-shepherd-sting-campaign-ends-in-court-14

- ^ http://pen.ci.santa-monica.ca.us/airport/PDF%20Files/LF%20Brochure.pdf SMO Landing Fee Program

- ^ Airport Park – Community & Cultural Services (CCS) – City of Santa Monica

- ^ "The Barker Hangar – Event Venue Santa Monica". Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Fowler, Kelsey (September 30, 2014). "Barker Hangar boxing fights return October 1". Santa Monica Daily Press. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ Charles Andrews (January 21, 2021). "BEST CONCERTS OF THE YEAR!". Santa Monica Daily Press. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ "Culture Watch - OUR NEW ART WORLD". Santa Monica Daily Press. July 2, 2020. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ "A free Disney drive-in movie theater is popping up in Santa Monica". Time Out Los Angeles. Retrieved April 23, 2021.

- ^ http://www.smmirror.com/?ajax#mode=single&view=31809

- ^ Dan Weikel (January 10, 2014). "Federal government seeks to dismiss Santa Monica Airport lawsuit". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Judge Dismisses the City of Santa Monica's Action Regarding the Santa Monica Municipal Airport". Aviation and Airport Development News. February 13, 2014. Retrieved February 18, 2014.

- ^ "Santa Monica Airport (SMO) History". Santa Monica Municipal Airport. October 14, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ "Election 2014: Santa Monica Voters Pass Measure LC, Defeat Measure D". Santa Monica Mirror. November 5, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "A Look Back On 45 Years Of Aviation Accidents/Incidents At Santa Monica Airport". Santa Monica Mirror. March 7, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ "Talk of shortened Santa Monica Airport runway heats up". Santa Monica Daily Press. March 2, 2015. Retrieved December 11, 2015.

- ^ http://argonautnews.com/faa-offers-runway-safety-alternative-for-santa-monica-airport/

- ^ FOX. "Santa Monica Airport to close in 2028". KTTV. Retrieved January 29, 2017.

- ^ "Santa Monica Rushes to Shorten SMO Runway". August 10, 2017.

- ^ "Santa Monica Airport Runway Project Set to Begin". September 25, 2017.

- ^ "Santa Monica Airport (SMO) Runway 3-21 Shortened". December 23, 2017.

- ^ [1]

- ^ LAX94FA198 Archived March 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ LAX01FA129 Archived October 10, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ LAX02FA028 Archived October 11, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Blankstein, Andrew (March 14, 2006). "TV Game Show Host, Wife Killed; Peter Tomarken of 'Press Your Luck' was piloting a small plane that crashed into Santa Monica Bay". LA Times Archives. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ "N16JR flight track". FlightAware. Retrieved May 18, 2008.

- ^ "WPR09FA102". Retrieved February 4, 2009.

- ^ Lozano, Alicia (January 28, 2009). "2 men killed in crash at Santa Monica Airport are identified". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved January 28, 2009.

- ^ Bloomekatz, Ari (August 2, 2009). "Pilot injured in small plane crash". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ http://www.dailybreeze.com/news/ci_15427971

- ^ "L.A. Now". Los Angeles Times. August 29, 2011.

- ^ https://app.ntsb.gov/pdfgenerator/ReportGeneratorFile.ashx?EventID=20110830X53111&AKey=1&RType=HTML&IType=FA%7Caccessdate=August 5, 2020

- ^ https://latimesblogs.latimes.com/lanow/2011/08/small-plane-crashes-into-yard-in-santa-monica.html

- ^ David Simpson (September 30, 2013). "No survivors after plane hits hangar at Santa Monica Airport". CNN. Retrieved September 30, 2013.

- ^ "Morley Builders Names Veteran Charles Muttillo as President To Succeed Mark Benjamin". Engineering News-Record. McGraw Hill Financial. October 1, 2013. Retrieved September 14, 2014.

- ^ https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/harrison-ford-plane-crash-aircraft-has-storied-wwii-history-n318666

- ^ "Harrison Ford crash: NTSB investigator says anytime a person survives an airplane crash is 'a good day'". Fox News. March 6, 2015.

- ^ "Harrison Ford injured in plane crash". USA Today. March 5, 2015.

- ^ https://gma.yahoo.com/harrison-ford-plane-crash-described-golfing-spine-surgeon-130331212--abc-news-celebrities.html

- ^ "Harrison Ford recovering after crash landing plane on golf course". Los Angeles Times. March 6, 2015.

- ^ "Harrison Ford Injured In Plane Crash On Golf Course". Huffington Post. March 5, 2015.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Santa Monica Airport. |

- Official website

- Museum of Flying

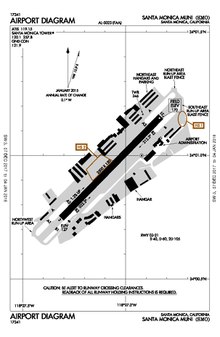

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective September 9, 2021

- Resources for this airport:

- FAA airport information for SMO

- AirNav airport information for KSMO

- ASN accident history for SMO

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart, Terminal Procedures

- 1950s aerial view looking west

- Airports in Los Angeles County, California

- Buildings and structures in Santa Monica, California

- Airfields of the United States Army Air Forces in California

- Airfields of the United States Army Air Forces Technical Service Command

- Landmarks in Santa Monica, California

- Westside (Los Angeles County)

- Airports established in 1924

- Proposed populated places in the United States

- 1924 establishments in California