Scheherazade

| Scheherazade شهرزاد | |

|---|---|

| One Thousand and One Nights character | |

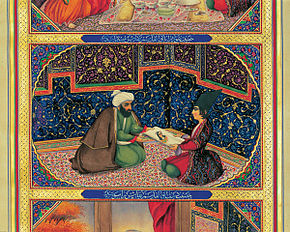

Scheherazade, painted in the 19th century by Sophie Anderson | |

| Portrayed by | Mili Avital, Catherine Zeta-Jones, Claude Jade, Anna Karina, María Montez, Cyrine Abdelnour, Sulaf Fawakherji, Annette Haven |

| In-universe information | |

| Gender | Female |

| Occupation | Queen consort |

| Family | The chief vizier (father) Dunyazad (sister) |

| Spouse | Shahryar |

| Children | 3 sons |

| Other names | Shahrazad, Shahrzad |

Scheherazade (/ʃəˌhɛrəˈzɑːd, -də/[1]) is a major female character and the storyteller in the frame narrative of the Middle Eastern collection of tales known as the One Thousand and One Nights.

Name[]

According to modern scholarship, the name Scheherazade derives from an Arabic form of the Middle Persian name Čehrāzād, which is composed of the words čehr ('lineage') and āzād ('noble, exalted').[2][3][4] The earliest forms of Scheherazade's name in Arabic sources include Shirazad (شيرازاد, Šīrāzād) in Masudi, and Shahrazad in Ibn al-Nadim.[5][6]

The name appears as Šahrazād in the Encyclopaedia of Islam[4] and as Šahrāzād in Encyclopædia Iranica.[3] Among standard 19th-century printed editions, the name appears as شهرزاد (Šahrazād) in Macnaghten's Calcutta edition (1839–1842)[7] and in the 1862 Bulaq edition,[8] and as شاهرزاد (Šāhrazād) in the Breslau edition (1825–1843).[9] Muhsin Mahdi's critical edition has شهرازاد (Šahrāzād).[10]

The spelling Scheherazade first appeared in English-language texts in 1801, borrowed from German usage.[1]

Narration[]

The story goes that the monarch Shahryar, on discovering that his first wife was unfaithful to him, resolved to marry a new virgin every day and have her beheaded the next morning before she could dishonour him. Eventually the vizier could find no more virgins of noble blood and offers his own daughter, Scheherazade, as the king's next bride.

In Sir Richard Burton's translation of The Nights, Scheherazade was described in this way:

Scheherazade had perused the books, annals, and legends of preceding Kings, and the stories, examples, and instances of bygone men and things; indeed it was said that she had collected a thousand books of histories relating to antique races and departed rulers. She had perused the works of the poets and knew them by heart; she had studied philosophy and the sciences, arts, and accomplishments; and she was pleasant and polite, wise and witty, well read and well bred.

Against her father's wishes, Scheherazade volunteered to marry the king. Once in the king's chambers, Scheherazade asked if she might bid one last farewell to her beloved younger sister, Dunyazad, who had secretly been prepared to ask Scheherazade to tell a story during the long night. The king lay awake and listened with awe as Scheherazade told her first story. The night passed by, and Scheherazade stopped in the middle. The king asked her to finish, but Scheherazade said there was no time, as dawn was breaking. So, the king spared her life for one day to finish the story the next night. The following night, Scheherazade finished the story and then began a second, more exciting tale, which she again stopped halfway through at dawn. Again, the king spared her life for one more day so that she could finish the second story.

Thus, the king kept Scheherazade alive day by day, as he eagerly anticipated the conclusion of the previous night's story. At the end of 1,001 nights, and 1,000 stories, Scheherazade finally told the king that she had no more tales to tell him. During the preceding 1,001 nights, however, the king had fallen in love with Scheherazade. He wisely spared her life permanently and made her his queen.

See also[]

- Scheherazade in popular culture

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Scheherazade". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Marzolph, Ulrich (2017). "Arabian Nights". In Kate Fleet; Gudrun Krämer; Denis Matringe; John Nawas; Everett Rowson (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (3rd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_COM_0021.

the narrator's name is of Persian origin, the Arabicised form Shahrazād being the equivalent of the Persian Chehr-āzād, meaning “of noble descent and/or appearance”.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ch. Pellat (2011). "Alf Layla wa-Layla". Encyclopædia Iranica.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hamori, A. (2012). "S̲h̲ahrazād". In P. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam (2nd ed.). Brill. doi:10.1163/1573-3912_islam_SIM_6771.

- ^ Robert Irwin (2004). The Arabian Nights: A Companion. Tauris Parke Paperbacks. p. 944 (Kindle loc).

- ^ Hamdan Muhammad Ali Hussein Ismail (حمدان محمد علي حسين إسماعيل) (2009). Ishkaliyat al-Tarjamah fi al-Adab al-Muqaran إشكالية الترجمة في الآدب المقارن. Al Manhal. p. 170. ISBN 9796500054087.

- ^ William Hay Macnaghten, ed. (1839). The Alif laila. 1. Calcutta, W. Thacker and co. p. 14.

- ^ Kitāb alf laylah wa-laylah. 1. Bulaq. 1862. p. 20.

- ^ Maximilian Habicht; Heinrich Leberecht Fleischer, eds. (1825). Tausend und eine Nacht — alf laylah wa-laylah : arabisch, nach einer Handschrift aus Tunis. 1. Breslau. p. 31.

- ^ Muhsin Mahdi, ed. (1984). Alf Layla wa-Layla. Brill. p. 66. ISBN 978-9004074316.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Scheherazade |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Scheherazade. |

- Female characters in literature

- Fictional queens

- Fictional storytellers

- One Thousand and One Nights characters

- Persian mythology

- Medieval legends