Scientific-Humanitarian Committee

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in German. (February 2009) Click [show] for important translation instructions. |

The Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (German: Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, WhK) was founded by Magnus Hirschfeld in Berlin on 14 or 15 May 1897, to campaign for social recognition of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people, and against their legal persecution. It was the first LGBT rights organization in history. The motto of the organization was "Justice through science", and the committee included representatives from various professions.[1][2][3]

History[]

The WhK was founded in Berlin-Charlottenburg, a locality of Berlin, on 14 or 15 May 1897 (four days before Oscar Wilde's release from prison) by Magnus Hirschfeld, a Jewish-German physician, sexologist and outspoken advocate for gender and sexual minorities. Original members of the WhK included Hirschfeld, publisher Max Spohr, lawyer and writer .[4] Adolf Brand, Benedict Friedländer, Hermann von Teschenberg and Kurt Hiller also joined the organization. A split happened in 1907, led by Friedländer.[1] In 1929, Hiller took over as chairman of the group from Hirschfeld. At its peak, the WhK had branches in approximately 25 cities in Germany, Austria and the Netherlands.

The committee was based in the Institute for Sexual Sciences in Berlin until the institute's destruction at the hands of Nazis in 1933. The WhK was affiliated with the World League for Sexual Reform, another group founded by Hirschfeld which had similar aims to the committee.[6] The committee had ties to gay organizations across the world, and from 1906 onward the body which crafted the committee's policy was made up of members from several European countries. In 1911, the Dutch branch of the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee was formed, and by 1914 a branch had formed in Austria.[1]

The WhK took a great deal of scientific theories on human sexuality from the institute such as the idea of a third sex between a man and a woman. The initial focus of the committee was to repeal Paragraph 175, an anti-gay piece of legislation of the Imperial Penal Code, which criminalized "coitus-like" acts between males. It also sought to demonstrate the innateness of homosexuality and thus make the criminal law against sodomy in Germany at the time inapplicable.

In campaigning against Paragraph 175, the committee argued that homosexuality was not a disease or moral failing, and said they reached this conclusion from scientific evidence. The group made other arguments against this law, saying for example that its repeal would reduce blackmailing behavior among male prostitutes.[2]

The committee also assisted defendants in criminal trials, conducted public lectures on sexual education, and gathered more than 6,000 signatures on a petition for the repeal of Paragraph 175.[1][7] The committee's opposition was not indiscriminate, and its petition did support preservation of criminal status for some homosexual acts, including cases between an adult and a minor under age 16. Work on promoting their petition began in 1897, and the committee particularly wanted signatures from those with prominent status in such fields as politics, medicine, art, and science. They sent thousands of letters to key figures such as Catholic priests, judges, lawmakers, journalists, and mayors. August Bebel signed the petition and took copies to the Reichstag to urge colleagues to add their names. Other signatories included Albert Einstein, Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, Rainer Maria Rilke, and Leo Tolstoy. World War I had a negative impact on the committee, with supporters and members going to fight in the war. The petition campaign largely fell by the wayside until the war was over.[1][3] Petitions were submitted in 1898, 1922, and 1925, but failed to gain the support of the parliament. The law continued to criminalize homosexuality until 1969 and was not entirely removed in West Germany until four years after East and West Germany became one country in 1994.

The committee had roughly 700 members at its peak and is considered an important milestone in the homosexual emancipation movement.[8] It existed for thirty-five years.[1]

Publications[]

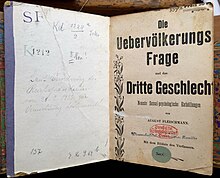

The WhK produced the Jahrbuch für sexuelle Zwischenstufen (Yearbook for Intermediate Sexual Types), a publication which reported the committee's activities and contained content ranging from articles about homosexuality among "primitive" people to literary analyses and case studies.[1] It was published regularly from 1899 to 1923 (sometimes quarterly) and more sporadically until 1933. Yearbook was the world's first scientific journal dealing with sexual variants.[9]

Another of the WhK's widespread publications was a brochure entitled Was soll das Volk vom Dritten Geschlecht wissen? (What Must Our Nation Know about the Third Sex?) that was produced alongside the committee's sexual education lectures. It offered information on homosexuality, pulling largely from the studies of the Institute for Sexual Sciences. The brochure offered a rare case of nonjudgmental insight into the existence of homosexuality and, as such, was frequently distributed by homosexuals to family members or to total strangers on public transport.[8]

Reformation attempts[]

In October 1949, Hans Giese joined with Hermann Weber (1882–1955), head of the Frankfurt local group from 1921 to 1933, to re-establish the group in Kronberg. Kurt Hiller worked with them briefly, but stopped due to personal differences after a few months. The group was dissolved in late 1949 or early 1950 and instead formed the Committee for Reform of the Sexual Criminal Laws (Gesellschaft für Reform des Sexualstrafrechts e. V.), which existed until 1960.[10][11]

In 1962 in Hamburg, Hiller, who had survived Nazi concentration camps and continued to fight against anti-gay repression, tried unsuccessfully to re-establish the WhK.[12]

New WhK[]

In 1998, a new group was formed with the same name.[13] Growing out of a group against politician Volker Beck in that year's election,[14] it is similar in name and general subject matter only, and takes more radical positions than the conservative LSVD. In 2001, its magazine Gigi was given a special award by the German Association of Lesbian and Gay Journalists.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g John Lauritsen; David Thorstad (1974), The Early Homosexual Rights Movement (1864–1935), New York: Times Change Press, ISBN 0-87810-027-X. Revised edition published 1995, ISBN 0-87810-041-5.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sengoopta, Chandak (1998). "Glandular Politics: Experimental Biology, Clinical Medicine, and Homosexual Emancipation in Fin-de-Siecle Central Europe". Isis. 89 (3): 445–473. ISSN 0021-1753.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Peters, Steve (February 18, 2019). "LGBT History Month 2019 Faces – Magnus Hirschfeld and the first LGBT+ film". Canterbury Christ Church University. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "Magnus Hirschfeld and HKW". Haus der Kulturen der Welt.

In 1897, together with Max Spohr, Eduard Oberg and Franz Joseph von Bülow, he founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee in Berlin Charlottenburg.

- ^ "Dinge, die wir suchen". magnus-hirschfeld.de. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ^ Dose, Ralf; Selwyn, Pamela Eve (January 2003). "The World League for Sexual Reform: Some possible approaches". Journal of the History of Sexuality. University of Texas Press. 12 (1): 1–15 – via Project MUSE.

Other corporate members were the Scientific Humanitarian Committee...

- ^ "Henry Gerber: Ahead of his time". The Washington Blade. October 3, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

...Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld founded the gay organization Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee (Scientific-Humanitarian Committee). Its first action was to draft a petition against Paragraph 175 with 6,000 signatures of prominent people in the arts, politics and the medical profession; it failed to have any effect.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Dose, Ralf (2014). Magnus Hirschfeld and the origins of the gay liberation movement. New York. p. 42. ISBN 978-1-58367-439-0. OCLC 870272914.

- ^ "Hirschfeld, Magnus (1868-1935)". glbtq, an encyclopedia of gay, lesbian, bisexual, trans and queer culture. Retrieved 16 November 2014.

- ^ Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller (2001), Mann für Mann. Ein biographisches Lexikon, Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp-Taschenbuch-Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-518-39766-4, ISBN 3-928983-65-2. Entries for Hans Giese p. 278, and Kurt Hiller p. 357: Citation.

- ^ Jürgen Müller, Review of: Andreas Pretzel (Ed.): NS-Opfer unter Vorbehalt. - Homosexuelle Männer in Berlin nach 1945, LIT-Verlag, Münster 2002

- ^ Online exhibition of the Magnus Hirschfeld Society: Kurt Hiller

- ^ whk - wissenschaftlich-humanitäres komitee

- ^ The history of the new WHK (german)

Further reading[]

- LGBT political advocacy groups in Germany

- LGBT history in Germany

- Magnus Hirschfeld

- 19th century in LGBT history

- 1897 establishments in Germany