Violence against LGBT people

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people frequently experience violence directed toward their sexuality or gender identity.[1][2] This violence may be enacted by the state, as in laws prescribing punishment for homosexual acts, or by individuals. It may be psychological or physical and motivated by biphobia, gayphobia, homophobia, lesbophobia, and transphobia. Influencing factors may be cultural, religious,[3][4][5] or political mores and biases.[6]

Currently, homosexual acts are legal in almost all Western countries, and in many of these countries violence against LGBT people is classified as a hate crime.[7] Outside the West, many countries are deemed potentially dangerous to their LGBT population due to both discriminatory legislation and threats of violence. These include countries where the dominant religion is Islam, most African countries (except South Africa), most Asian countries (except the LGBT-friendly Asian countries of Israel, Japan, Taiwan, Thailand and the Philippines), and some former-Communist countries such as Russia, Poland (LGBT-free zone), Serbia, Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[5] Such violence is often associated with religious condemnation of homosexuality or conservative social attitudes that portray homosexuality as an illness or a character flaw.[3][4]

In Europe, the European Union's Employment Equality Framework Directive and Charter of Fundamental Rights offer some protection against sexuality-based discrimination.

Historically, state-sanctioned persecution of homosexuals was mostly limited to male homosexuality, termed "sodomy". During the medieval and early modern period, the penalty for sodomy was usually death.[8] During the modern period (from the 19th century to the mid-20th century) in the Western world, the penalty was usually a fine or imprisonment.

There was a drop in locations where homosexual acts remained illegal from 2009 when there were 80 countries worldwide (notably throughout the Middle East, Central Asia and in most of Africa, but also in some of the Caribbean and Oceania) with five carrying the death penalty[9] to 2016 when 72 countries criminalized consensual sexual acts between adults of the same sex.[10]

Brazil, a country with LGBT rights protections and legal same-sex marriage, is reported to have the world's highest LGBT murder rate, with more than 380 murders in 2017 alone, an increase of 30% compared to 2016. This is usually not considered a hate crime in Brazil but a misinterpretation of skewed data resulting from relatively higher crime rates in the country in general when compared to world averages, rather than the LGBT population being a specific target.[11]

In some countries, 85% of LGBT students experience homophobic and transphobic violence in school, and 45% of transgender students drop out of school.[12]

State-sanctioned violence[]

Historic[]

The Middle East[]

An early law against sexual intercourse between men is recorded in Leviticus by the Hebrew people, prescribing the death penalty. A violent law regarding homosexual intercourse is prescribed in the Middle Assyrian Law Codes (1075 BCE), stating: "If a man lay with his neighbor, when they have prosecuted him (and) convicted him, they shall lie with him (and) turn him into a eunuch".

In the account given in Tacitus' Germania, the death penalty was reserved for two kinds of capital offenses: military treason or desertion was punished by hanging, and so was moral infamy (cowardice and homosexuality: ignavos et imbelles at corpore infames); Gordon translates corpore infames as "unnatural prostitutes"; Tacitus refers to male homosexuality, see David F. Greenberg, The construction of homosexuality, p. 242 f. Scholarship compares the later Germanic concept of Old Norse argr, Langobardic arga, which combines the meanings "effeminate, cowardly, homosexual", see Jaan Puhvel, 'Who were the Hittite hurkilas pesnes?' in: A. Etter (eds.), O-o-pe-ro-si (FS Risch), Walter de Gruyter, 1986, p. 154.

Europe[]

Laws and codes prohibiting homosexual practice were in force in Europe from the fourth[13] to the twentieth centuries.

Republican Rome[]

In Republican Rome, the poorly attested Lex Scantinia penalized an adult male for committing a sex crime (stuprum) against an underage male citizen (ingenuus). It is unclear whether the penalty was death or a fine. The law may also have been used to prosecute adult male citizens who willingly took a receiving role in same-sex acts, but prosecutions are rarely recorded and the provisions of the law are vague; as John Boswell has noted, "if there was a law against homosexual relations, no one in Cicero's day knew anything about it."[14] When the Roman Empire came under Christian rule, all male homosexual activity was increasingly repressed, often on pain of death.[13] In 342 CE, the Christian emperors Constantius and Constans declared same-sex marriage to be illegal.[15] Shortly after, in the year 390 CE, emperors Valentinian II, Theodosius I and Arcadius declared homosexual sex to be illegal and those who were guilty of it were condemned to be publicly burned alive.[13] Emperor Justinian I (527–565 CE) made homosexuals a scapegoat for problems such as "famines, earthquakes, and pestilences."[16]

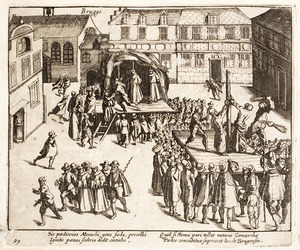

France and Florence[]

During the Middle Ages, the Kingdom of France and the City of Florence also instated the death penalty. In Florence, a young boy named Giovanni di Giovanni (1350–1365?) was castrated and burned between the thighs with a red-hot iron by court order under this law.[17][18] These punishments continued into the Renaissance, and spread to the Swiss canton of Zürich. Knight Richard von Hohenberg (died 1482) was burned at the stake together with his lover, his young squire, during this time. In France, French writer Jacques Chausson (1618–1661) was also burned alive for attempting to seduce the son of a nobleman.

England[]

In England, the Buggery Act of 1533 made sodomy and bestiality punishable by death.[19] This act was superseded in 1828, but sodomy remained punishable by death under the new act until 1861, although the last executions were in 1835.[20]

Malta[]

In seventeenth century Malta, Scottish voyager and author William Lithgow, writing in his diary in March 1616, claims a Spanish soldier and a Maltese teenage boy were publicly burnt to ashes for confessing to have practiced sodomy together.[21][22] To escape this fate, Lithgow further claimed that a hundred bardassoes (boy prostitutes) sailed for Sicily the following day.[21]

The Holocaust[]

In Nazi Germany and Occupied Europe, homosexuals were among the groups targeted by the Holocaust (See Persecution of homosexuals in Nazi Germany). (In 1936, the poet Federico García Lorca was executed by right-wing rebels who established Franco's dictatorship in Spain, Hitler's ally.)

Contemporary[]

| Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties: | |

Death | Prison; death not enforced |

Death under militias | Prison, w/ arrests or detention |

Prison, not enforced1 | |

| Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions: | |

Marriage | Extraterritorial marriage2 |

Civil unions | |

Limited foreign | Optional certification |

None | Restrictions of expression |

1No emprisonment in the past three years or moratorium on law.

2Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships.

As of August 2020, 69 countries criminalize consensual sexual acts between adults of the same sex.[10] They are punishable by death in nine countries:

- Brunei

- Iran (fourth conviction)[23]

- Mauritania[23]

- Qatar[23]

- Saudi Arabia: Although the maximum punishment for homosexuality is execution, the government tends to use other punishments (fines, prison sentence, and whipping), unless it feels that homosexuals have challenged state authority by engaging in LGBT social movements.[24]

- Yemen[23]

- Parts of Nigeria and Somalia[10]

Countries where homosexual acts are criminalized but not punished by death, by region, include:[25]

Africa

- Algeria, Burundi, Cameroon, Chad, Comoros, Egypt, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Libya, Malawi, Morocco, Namibia, Nigeria (death penalty in some states), Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia (death penalty in some states), South Sudan, Sudan,[26] Swaziland, Tanzania, Togo, Tunisia, Uganda, Zambia, Zimbabwe

Asia

- Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Kuwait, Malaysia, Aceh, Maldives, Oman, Pakistan, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Syria, Turkmenistan, United Arab Emirates, Uzbekistan, Gaza Strip under Palestinian Authority

America

- Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines

Pacific Islands

Afghanistan, where such acts remain punishable with fines and a prison sentence, dropped the death penalty after the fall of the Taliban in 2001, who had mandated it from 1996. India criminalized homosexuality until June 2, 2009, when the High Court of Delhi declared section 377 of the Indian Penal Code invalid.[27]

Jamaica has some of the toughest sodomy laws in the world, with homosexual activity carrying a ten-year jail sentence.[28][29][30]

International human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International condemn laws that make homosexual relations between consenting adults a crime.[31][32] Since 1994, the United Nations Human Rights Committee has also ruled that such laws violated the right to privacy guaranteed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.[33][34][35]

Criminal assault[]

Even in countries where homosexuality is legal (most countries outside of Africa and the Middle East), there are reports of homosexual people being targeted with bullying or physical assault or even homicide.

According to the Grupo Gay da Bahia (GGB), Brazil's oldest gay rights NGO, the rate of murders of homosexuals in Brazil is particularly high, with a reported 3,196 cases over the 30-year period of 1980 to 2009 (or about 0.7 cases per 100,000 population per annum).[36] At least 387 LGBT Brazilians were murdered in 2017.[37]

GGB reported 190 documented alleged homophobic murders in Brazil in 2008, accounting for about 0.5% of intentional homicides in Brazil (homicide rate 22 per 100,000 population as of 2008). 64% of the victims were gay men, 32% were trans women or transvestites, and 4% were lesbians.[38] By comparison, the FBI reported five homophobic murders in the United States during 2008, corresponding to 0.03% of intentional homicides (homicide rate 5.4 per 100,000 population as of 2008).

The numbers produced by the Grupo Gay da Bahia (GGB) have occasionally been contested on the grounds that they include all murders of LGBT people reported in the media — that is, not only those motivated by bias against homosexuals. Reinaldo de Azevedo, columnist of the right-wing Veja magazine, Brazil's most read weekly publication, called the GGB's methodology "unscientific" based on the above objection: that they make no distinction between murders motivated by bias and those that were not.[39] On the high level of murders of transsexuals, he suggested transsexuals' allegedly high involvement with the drug trade may expose them to higher levels of violence as compared to non-transgender homosexuals and heterosexuals.

In many parts of the world, including much of the European Union and United States, acts of violence are legally classified as hate crimes, which entail harsher sentences if convicted. In some countries, this form of legislation extends to verbal abuse as well as physical violence.

Violent hate crimes against LGBT people tend to be especially brutal, even compared to other hate crimes: "an intense rage is present in nearly all homicide cases involving gay male victims". It is rare for a victim to just be shot; he is more likely to be stabbed multiple times, mutilated, and strangled. "They frequently involved torture, cutting, mutilation... showing the absolute intent to rub out the human being because of his (sexual) preference".[40] In a particularly brutal case in the United States, on March 14, 2007, in Wahneta, Florida, 25-year-old Ryan Keith Skipper was found dead from 20 stab wounds and a slit throat. His body had been dumped on a dark, rural road less than 2 miles from his home. His two alleged attackers, William David Brown, Jr., 20, and Joseph Eli Bearden, 21, were indicted for robbery and first-degree murder. Highlighting their malice and contempt for the victim, the accused killers allegedly drove around in Skipper's blood-soaked car and bragged of killing him. According to a sheriff's department affidavit, one of the men stated that Skipper was targeted because "he was a faggot."[41]

In Canada in 2008, police-reported data found that approximately 10% of all hate crimes in the country were motivated by sexual orientation. Of these, 56% were of a violent nature. In comparison, 38% of all racially motivated offenses were of a violent nature.[41]

In the same year in the United States, according to Federal Bureau of Investigation data, though 4,704 crimes were committed due to racial bias and 1,617 were committed due to sexual orientation, only one murder and one forcible rape were committed due to racial bias, whereas five murders and six rapes were committed based on sexual orientation.[42] In Northern Ireland in 2008, 160 homophobic incidents and 7 transphobic incidents were reported. Of those incidents, 68.4% were violent crimes; significantly higher than for any other bias category. By contrast, 37.4% of racially motivated crimes were of a violent nature.[41]

People's ignorance of and prejudice against LGBT people can contribute to the spreading of misinformation about them and subsequently to violence. In 2018, a transgender woman was killed by a mob in Hyderabad, India, following false rumors that transgender women were sex trafficking children. Three other transgender women were injured in the attack.[43]

Recent research on university-level students indicated the importance of queer visibility and its impact in creating a positive experience for LGBTIQ+ members of a campus community, this can reduce the impact and effect of incidents on youth attending university. When there is a poor climate - students are much less likely to report incidents or seek help.[44]

Violence at universities[]

In the United States during the past few years, colleges and universities have taken major steps to prevent sexual harassment from taking place on campus, but students have reported violence due to their sexual orientation.[45] Sexual harassment can include "non-contact forms" such as making jokes or comments and "contact forms" like forcing students to commit sexual acts.[45] Even though little information exists with LGBT violence taking place at higher learning institutions, different communities are taking a stand against the violence. Many LGBT rape survivors said they experienced their first assault before the age of 25, and that many arrive on campus with this experience. Almost half of bisexual women experience their first assault between the ages of 18–24, and most of these take place unreported on college campuses.[45] Though the Federal Bureau of Investigation changed what the "federal" definition of what rape means (for reporting purposes) in 2012, local state governments still determine how campus violence cases are treated. Catherine Hill and Elana Silva said in Drawing the Line: Sexual Harassment on Campus, "Students who admit to harassing other students generally don't see themselves as rejected suitors, rather misunderstood comedians."[46] Most students who commit sexual violence towards other students do it to boost their own ego, believing that their actions are humorous. More than 46% of sexual harassment towards LGBT people still goes unreported.[46] National resources have been created to deal with the issue of sexual violence and various organizations such as The American Association of University Women and the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence are established to provide information and resources for those who have been sexually harassed.[46]

Legislation against homophobic hate crimes[]

This section's factual accuracy may be compromised due to out-of-date information. (May 2013) |

Members of the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe began describing hate crimes based on sexual orientation (as opposed to generic anti-discrimination legislation) to be counted as aggravating circumstance in the commission of a crime in 2003.[47]

The United States does not have federal legislation marking sexual orientation as criteria for hate crimes, but several states, including the District of Columbia, enforce harsher penalties for crimes where real or perceived sexual orientation may have been a motivator. Among these 12 countries as well, only the United States has criminal law that specifically mentions gender identity, and even then only in 11 states and the District of Columbia.[41] In November 2010, the United Nations General Assembly voted 79–70 to remove "sexual orientation" from the Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, a list of unjustified reasons for executions, replacing it with "discriminatory reasons on any basis".[48] The resolution specifically mentions a large number of groups, including race, religion, linguistic differences, refugees, street children and indigenous peoples.[49]

Legal and police response to these types of hate crimes is hard to gauge, however. Lack of reporting by authorities on the statistics of these crimes and under-reporting by the victims themselves are factors for this difficulty.[41] Often a victim will not report a crime as it will shed unwelcome light on their orientation and invite more victimization.[50]

Alleged judicative bias[]

The neutrality of this section is disputed. (March 2017) |

"It's pretty disturbing that somebody that [kills] a person in cold blood gets out very quickly…."

Legal defenses like the gay panic defense allow for more lenient punishments for people accused of beating, torturing, or killing homosexuals because of their orientation. These arguments posit that the attacker was so enraged by their victim's advances as to cause temporary insanity, leaving them unable to stop themselves or tell right from wrong. In these cases, if the loss of faculties is proven, or sympathized to the jury, an initially severe sentence may be significantly reduced. In several common law countries, the mitigatory defense of provocation has been used in violent attacks against LGBT persons, which has led several Australian states and territories to modify their legislation, in order to prevent or reduce the using of this legal defense in cases of violent responses to non-violent homosexual advances.

There have been several highly publicized cases where people convicted of violence against LGBT people have received shorter sentences. One such case is that of Kenneth Brewer. On 30 September 1997, he met Stephen Bright at a local gay bar. He bought the younger man drinks and they later went back to Brewer's apartment. While there, Brewer made a sexual advance toward Bright, and Bright beat him to death. Bright was initially charged with second-degree murder, but he was eventually convicted of third-degree assault and was sentenced to one year in prison.[51][52] Cases like Bright's are not isolated. In 2001, Aaron Webster was beaten to death by a group of youths armed with baseball bats and a pool cue while hanging around an area of Stanley Park frequented by gay men. Ryan Cran was convicted of manslaughter in the case in 2004 and released on parole in 2009 after serving only 4 years of his six-year sentence.[50] Two youths were tried under Canada's Youth Criminal Justice Act and sentenced to three years after pleading guilty. A fourth assailant was acquitted.[50]

Judges are not immune to letting their own prejudices affect their judgment either. In 1988, Texas Judge Jack Hampton gave a man 30 years for killing two gay men, instead of the life sentence requested by the prosecutor. After handing down his judgment, he said: "I don't much care for queers cruising the streets picking up teenage boys ...[I] put prostitutes and gays at about the same level ... and I'd be hard put to give somebody life for killing a prostitute."[51]

In 1987, a Florida judge trying a case concerning the beating to death of a gay man asked the prosecutor, "That's a crime now, to beat up a homosexual?" The prosecutor responded, "Yes, sir. And it's also a crime to kill them." "Times have really changed," the judge replied. The judge, Daniel Futch, maintained that he was joking, but was removed from the case.[40][51]

Attacks on gay pride parades[]

LGBT Pride Parades in East European, Asian and South American countries often attract violence because of their public nature. Though many countries where such events take place attempt to provide police protection to participants, some would prefer that the parades not happen, and police either ignore or encourage violent protesters. The country of Moldova has shown particular contempt to marchers, shutting down official requests to hold parades and allowing protesters to intimidate and harm any who try to march anyway. In 2007, after being denied a request to hold a parade, a small group of LGBT people tried to hold a small gathering. They were surrounded by a group twice their size who shouted derogatory things at them and pelted them with eggs. The gathering proceeded even so, and they tried to lay flowers at the Monument to the Victims of Repression. They were denied the opportunity, however, by a large group of police claiming they needed permission from city hall.[41]

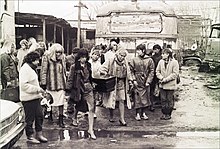

The following year, a parade was again attempted. A bus carried approximately 60 participants to the capital, but before they could disembark, an angry crowd surrounded the bus. They shouted things like "let's get them out and beat them up", and "beat them to death, don't let them escape" at the frightened passengers. The mob told the activists that if they wanted to leave the bus unharmed, they would have to destroy all of their pride materials. The passengers complied and the march was called off. All the while, police stood passively about 100 meters away, taking no action even though passengers claimed at least nine emergency calls were made to police while on the bus.[41][53][54]

Russia's officials are similarly averse to Pride Parades. Mayor of Moscow Yury Luzhkov has repeatedly banned marches, calling them "satanic".[55] Pride participants instead tried to peacefully assemble and deliver a petition to city hall regarding the right of assembly and freedom of expression. They were met by skinheads and other protesters, and police who had closed off the square and immediately arrested activists as they entered. As some were being arrested, other participants were attacked by protesters. Police did nothing. Around eleven women and two men were arrested and left in the heat, denied medical attention, and verbally abused by police officers. The officers told the women, "No one needs lesbians, no one will ever get you out of here." When participants were released from custody hours later, they were pelted by eggs and shouted at by protesters who had been waiting.[41][56]

Hungary, on the other hand, has tried to afford the best protection they can to marchers, but cannot stem the flow of violence. In 2008, hundreds of people participated in the Budapest Dignity March. Police, on alert due to attacks on two LGBT-affiliated businesses earlier in the week, erected high metal barriers on either side of the street the march was to take place on. Hundreds of angry protesters threw petrol bombs and rocks at police in retaliation. A police van was set on fire and two police officers were injured in the attacks. During the parade itself, protesters threw Molotov cocktails, eggs and firecrackers at marchers. At least eight participants were injured.[57] Forty-five people were detained in connection with the attacks, and observers called the spectacle "the worst violence during the dozen years the Gay Pride Parade has taken place in Budapest".[41][58]

In Israel, three marchers in a gay pride parade in Jerusalem on June 30, 2005, were stabbed by Yishai Shlisel, a Haredi Jew. Shlisel claimed he had acted "in the name of God". He was charged with attempted murder.Ten years later, On 30 July 2015, six marchers were injured, again by Yishai Shlisel when he stabbed them. It was three weeks after he was released from jail. One of the victims, 16-year-old Shira Banki, died of her wounds at the Hadassah Medical Center three days later, on 2 August 2015. Shortly after, Prime Minister Netanyahu offered his condolences, adding "We will deal with the murderer to the fullest extent of the law."

In 2019, the gay pride parade in Detroit was infiltrated by armed neo-nazis who reportedly claimed they wanted to spark "Charlottesville 2.0" referring to the Unite the Right demonstration in 2017 which resulted in the murder of Heather Heyer, and many others injured.[59]

On 20 July 2019, the first Białystok equality march was held in Białystok, a Law and Justice party stronghold,[60] surrounded by Białystok county which is a declared LGBT-free zone.[61] Two weeks before the march Archbishop Tadeusz Wojda delivered a proclamation to all churches in Podlaskie Voivodeship and Białystok stating that pride marches were "blasphemy against God".[61] Wojda also asserted that the march was "foreign" and thanked those who "defend Christian values".[60] Approximately a thousand pride marchers were opposed by thousands of members of far-right groups, ultra football fans, and others.[62] Firecrackers were tossed at the marchers, homophobic slogans were chanted, and the marchers were pelted with rocks and bottles.[61][60][62] Dozens of marchers were injured.[61] Amnesty International criticized the police response, saying they had failed to protect marchers and "failed to respond to instances of violence".[63] According to the New York Times, similar to the manner in which the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville shocked Americans, the violence in Białystok raised public concern in Poland over anti-LGBT propaganda.[61]

Advocacy in song lyrics[]

As a result of the strong anti-homosexual culture in Jamaica, many reggae and dancehall artists, such as Buju Banton, Elephant Man, Sizzla, have published song lyrics advocating violence against homosexuals. Similarly, hip-hop music occasionally includes aggressively homophobic lyrics,[64] but has since appeared to reform.

Banton wrote a song when he was 15 years old that became a hit when he released it years later in 1992 called "Boom Bye Bye". The song is about murdering homosexuals and "advocated the shooting of gay men, pouring acid on them and burning them alive."[29] A song by Elephant Man proclaims: "When you hear a lesbian getting raped/It's not our fault ... Two women in bed/That's two sodomites who should be dead."[28]

Canadian activists have sought to deport reggae artists from the country due to homophobic content in some of their songs, which they say promote anti-gay violence. In the UK, Scotland Yard has investigated reggae lyrics and Sizzla was barred from entering the United Kingdom in 2004 over accusations his music promotes murder.[29][65]

Gay rights advocates have started the group Stop Murder Music to combat what they say is the promotion of hate and violence by artists. The group organized protests, causing some venues to refuse to allow the targeted artists to perform, and the loss of sponsors. In 2007, the group asked reggae artists to promise "not to produce music or make public statements inciting hatred against gay people. Neither can they authorise the re-release of previous homophobic songs." Several artists signed that agreement, including Buju Banton, Beenie Man, Sizzla and Capleton,[29] but some later denied signing it.[28][66]

During the 1980s, skinheads in North America who promoted emerging neo-Nazi pop culture and racist rock songs increasingly went to punk rock concerts with anti-gay music advocating violence.[67]

Motivations[]

Macho culture and social homophobia[]

This section possibly contains original research. (April 2013) |

The vast majority of homophobic criminal assault is perpetrated by male aggressors on male victims, and is connected to aggressive heterosexual machismo or male chauvinism. Theorists including Calvin Thomas and Judith Butler have suggested that homophobia can be rooted in an individual's fear of being identified as gay. Homophobia in men is correlated with insecurity about masculinity.[64][68][69] For this reason, allegedly homophobia is rampant in sports, and in the subculture of its supporters, that are considered stereotypically "male", such as football and rugby.[70]

These theorists have argued that a person who expresses homophobia does so not only to communicate their beliefs about the class of gay people, but also to distance themselves from this class and its social status. Thus, by distancing themselves from gay people, they are reaffirming their role as a heterosexuals in a heteronormative culture,[71] thereby attempting to prevent themselves from being labeled and treated as a gay person.[71]

Various psychoanalytic theories explain homophobia as a threat to an individual's own same-sex impulses, whether those impulses are imminent or merely hypothetical. This threat causes repression, denial or reaction formation.[72]

Religion[]

Religious texts[]

This section uncritically uses texts from within a religion or faith system without referring to secondary sources that critically analyze them. (May 2016) |

Some verses of the Bible are often interpreted as forbidding homosexual relations.[73][74]

Thou shalt not lie with mankind, as with womankind: it is abomination.

— Leviticus 18:22

And if a man lie with mankind, as with womankind, both of them have committed an abomination: they shall surely be put to death; their blood shall be upon them.

— Leviticus 20:13

The above verses are the cause of tension between the devout of the Abrahamic religions and members of the LGBT community. It is viewed by many as an outright condemnation of homosexual acts between men, and, more commonly in ancient times than today, justification for violence.

In the Religion Dispatches magazine, Candace Chellew-Hodge argues that the six or so verses that are often cited to condemn LGBT people are referring instead to "abusive sex." She states that the Bible has no condemnation for "loving, committed, gay and lesbian relationships" and that Jesus was silent on the subject.[75]

Christianity[]

In today's society, many Christian denominations welcome people attracted to the same sex, but teach that same sex relationships and homosexual sex are sinful.[76] These denominations include the Catholic Church,[77][78] the Eastern Orthodox church,[79] the Methodist Church,[76][80][81][82] and many other mainline denominations, such as the Reformed Church in America[83] and the American Baptist Church,[84] as well as Conservative Evangelical organizations and churches, such as the Evangelical Alliance,[85] and the Southern Baptist Convention.[86][87][88] Likewise, Pentecostal churches such as the Assemblies of God,[89] as well as Restorationist churches, like Jehovah's Witnesses and The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, also take the position that homosexual activity is immoral.[90][91]

Some Christian groups advocate conversion therapy and promote ex-gay groups. One such group, Exodus International, argued that conversion therapy may be a useful tool for decreasing same-sex desires,[92] and, while former affiliates of Exodus continue with such views, Exodus has since repudiated the organization's mission[93] and apologised for the pain and hurt and promoting "sexual orientation change efforts and reparative theories about sexual orientation that stigmatized parents."[94][95] The medical and scientific consensus in the United States is that conversion therapy is likely harmful and should be avoided because it may exploit guilt and anxiety, thereby damaging self-esteem and leading to depression and even suicide.[96][97][98] There is a broad concern in the mental health community that the advancement of conversion therapy itself causes social harm by disseminating inaccurate views about sexual orientation and the ability of gay, lesbian and bisexual people to lead happy, healthy lives.[96] This promotion of the idea that homosexuality is immoral and can be corrected may make would-be attackers of homosexuals feel justified in that they are "doing God's work" by ridding the world of LGBT people.[99]

The Catholic Church teaches that a homosexual orientation is not sinful and that LGBT people are to be treated with compassion and respect, as all others are. It also teaches that sex is meant to be had between opposite sex spouses. A 1992 letter from Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the future Pope Benedict XVI, condemned gay bashing.[100] It said that LGBT people "have the same rights as all persons including the right of not being treated in a manner which offends their personal dignity."[101] It adds that:[101][102]

It is deplorable that homosexual persons have been and are the object of violent malice in speech or in action. Such treatment deserves condemnation from the Church's pastors wherever it occurs. It reveals a kind of disregard for others which endangers the most fundamental principles of a healthy society. The intrinsic dignity of each person must always be respected in word, in action and in law.

However, in the same letter Ratzinger suggested that an increase in anti-gay violence is unsurprising if laws are introduced to protect homosexual behavior:[101]

...when civil legislation is introduced to protect behavior to which no one has any conceivable right, neither the church nor society at large should be surprised when other distorted notions and practices gain ground and irrational and violent reactions increase.

Pope Benedict XVI, then the leader of the Roman Catholic Church stated that "protecting" humanity from homosexuality was just as important as saving the world from climate change and that all relationships beyond traditional heterosexual ones are a "destruction of God's work."[99] Pope Francis has been seen as more welcoming to LGBT people, saying to a gay man that "God made you like this. God loves you like this. The Pope loves you like this and you should love yourself and not worry about what people say."[103][104][105][106]

Islam[]

The Quran cites the story of the "people of Lot" (also known as the people of Sodom and Gomorrah), destroyed by the wrath of Allah because they engaged in lustful carnal acts between men.

Scholars of Islam, such as Shaykh al-Islām Imam Malik, and Imam Shafi amongst others, ruled that Islam disallowed homosexuality and ordained capital punishment for a person guilty of it.[107]

The legal punishment for sodomy has varied among juristic schools: some prescribe capital punishment; while other prescribe a milder discretionary punishment. Homosexual activity is a crime and forbidden in most Muslim-majority countries. In some relatively secular Muslim-majority countries such as Indonesia,[108] Jordan and Turkey, this is not the case.

The Quran, much like the Bible and Torah, has a vague condemnation of homosexuality and how it should be dealt with, leaving it ambiguous. For this reason, Islamic jurists have turned to the collections of the hadith (sayings of Muhammad) and Sunnah (accounts of his life). These, on the other hand, are perfectly clear and particularly harsh.[109] Ibn al-Jawzi records Muhammad as cursing sodomites in several hadith, and recommending the death penalty for both the active and passive partners in same-sex acts.[110]

Sunan al-Tirmidhi again reports Muhammad as having prescribed the death penalty for both the active and the passive partner: "Whoever you find committing the sin of the people of Lot, kill them, both the one who does it and the one to whom it is done."[107] The overall moral or theological principle is that a person who performs such actions challenges the harmony of God's creation, and is therefore a revolt against God.[111]

These views vary depending upon sect. It is noteworthy to point out that Quranists (those who do not integrate the aforementioned Hadiths into their belief system) do not advocate capital punishment.[112]

Some imams still preach their views, stating that homosexuals and "women who act like men" should be executed under the Islamic law. Abu Usamah at Green Lane Mosque in Birmingham defended his words to followers by saying "If I were to call homosexuals perverted, dirty, filthy dogs who should be executed, that's my freedom of speech, isn't it?"[113]

Other contemporary Islamic views are that the "crime of homosexuality is one of the greatest of crimes, the worst of sins and the most abhorrent of deeds".[114] Homosexuality is considered the 11th major sin in Islam, in the days of the companions of Muhammad, a slave boy was once forgiven for killing his master who sodomized him.[115]

The 2016 Orlando nightclub shooting was at the time the deadliest mass shooting by an individual and remains the deadliest incident of violence against LGBT people in U.S. history.[116][117][118] On June 12, 2016, Omar Mateen killed 49 people and wounded more than 50 at Pulse gay nightclub in Orlando, Florida.[119] The act has been described by investigators as an Islamic terrorist attack and a hate crime.[120][121]

See also[]

- Prejudicial attitudes

- Anti-LGBT rhetoric

- Heterosexism

- LGBT stereotypes

- Violence

- Corrective rape

- Significant acts of violence against LGBT people

- Suicide among LGBT youth

- UK violence against LGBT people

- US violence against LGBT people

- US LGBT youth homelessness

- See also

- Bash Back!

- Brandon Teena

- Matthew Shepard

- Westboro Baptist Church

- Faithful Word Baptist Church

- Admiral Duncan pub bombing

- The Yogyakarta Principles

- Trust and safety issues in online dating services

- LGBT people in prison

- Education sector responses to LGBT violence

References[]

- ^ Meyer, Doug (December 2012). "An Intersectional Analysis of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) People's Evaluations of Anti-Queer Violence". Gender & Society. 26 (6): 849–873. doi:10.1177/0891243212461299. S2CID 145812781.

- ^ "Violence Against the Transgender Community in 2019 | Human Rights Campaign".

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stewart, Chuck (2009). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of LGBT Issues Worldwide (Volume 1). Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. pp. 4, 7, 85–86. ISBN 978-0313342318.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stewart, Chuck (2009). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of LGBT Issues Worldwide (Volume 2). Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. pp. 6–7, 10–11. ISBN 978-0313342356.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stewart, Chuck (2009). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of LGBT Issues Worldwide (Volume 3). Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. pp. 1, 6–7, 36, 65, 70. ISBN 978-0-313-34231-8.

- ^ Meyer, Doug (2015). Violence against Queer People. Rutgers University Press. Archived from the original on 2019-05-15. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ^ Stotzer, R.: Comparison of love Crime Rates Across Protected and Unprotected Groups, Williams Institute, 2007–06. Retrieved on 2007-08-09.

- ^ Reggio, Michael (1999-02-09). "History of the Death Penalty". PBS Frontline. Retrieved 2020-02-06.

- ^ "New Benefits for Same-Sex Couples May Be Hard to Implement Abroad"ABC News. June 22, 2009. 2009 Report on State Sponsored Homophobia (2009) Archived 2011-01-31 at the Wayback Machine, published by The International Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans and Intersex Association.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "ILGA publishes 2010 report on State sponsored homophobia throughout the world". International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. 2010. Archived from the original on 2014-03-23.

- ^ "Brazil has world's highest LGBT murder rate, with 100s killed in 2017 - MambaOnline - Gay South Africa online". MambaOnline - Gay South Africa online. 2018-01-24. Retrieved 2018-03-29.

- ^ "Report shows homophobic and transphobic violence in education to be a global problem".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c (Theodosian Code 9.7.6): All persons who have the shameful custom of condemning a man's body, acting the part of a woman's to the sufferance of alien sex (for they appear not to be different from women), shall expiate a crime of this kind in avenging flames in the sight of the people.

- ^ John Boswell, Christianity, Social Tolerance, and Homosexuality: Gay People in Western Europe from the Beginning of the Christian Era to the Fourteenth Century (University of Chicago Press, 1980), pp. 63, 67–68, quotation on p. 69. See also Craig Williams, Roman Homosexuality: Ideologies of Masculinity in Classical Antiquity (Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 116; Eva Cantarella, Bisexuality in the Ancient World (Yale University Press, 1992), p. 106ff.; Thomas A.J. McGinn, Prostitution, Sexuality and the Law in Ancient Rome (Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 140–141; Amy Richlin, The Garden of Priapus: Sexuality and Aggression in Roman Humor (Oxford University Press, 1983, 1992), pp. 86, 224; Jonathan Walters, "Invading the Roman Body," in Roman Sexualites (Princeton University Press, 1997), pp. 33–35, noting particularly the overly broad definition of the Lex Scantinia by Adolf Berger, Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law (American Philosophical Society, 1953, reprinted 1991), pp. 559 and 719. Freeborn Roman men could engage in sex with males of lower status, such as prostitutes and slaves, without moral censure or losing their perceived masculinity, as long as they took the active, penetrating role; see Sexuality in ancient Rome.

- ^ Theodosian Code 9.8.3: "When a man marries and is about to offer himself to men in womanly fashion (quum vir nubit in feminam viris porrecturam), what does he wish, when sex has lost all its significance; when the crime is one which it is not profitable to know; when Venus is changed to another form; when love is sought and not found? We order the statutes to arise, the laws to be armed with an avenging sword, that those infamous persons who are now, or who hereafter may be, guilty may be subjected to exquisite punishment.

- ^ Justinian Novels 77, 144; Michael Brinkschröde, "Christian Homophobia: Four Central Discourses," in Combatting Homophobia: Experiences and Analyses Pertinent to Education (LIT Verlag, 2011), p. 166.

- ^ Rocke, Michael (1996). Forbidden Friendships, Homosexuality and Male Culture in Renaissance Florence. Oxford University Press. pp. 24, 227, 356, 360. ISBN 0-19-512292-5.

- ^ Meyer, Michael J (2000). Literature and Homosexuality. Rodopi. p. 206. ISBN 90-420-0519-X.

- ^ "The Buggery Act 1533". British Library. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Dryden, Steven. "The Men Killed Under the Buggery Act". British Library. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Buttigieg, Emanuel (2011). Nobility, Faith and Masculinity: The Hospitaller Knights of Malta, c.1580-c.1700. A & C Black. p. 156. ISBN 9781441102430.

- ^ Brincat, Joseph M. (2007). "Book reviews" (PDF). Melita Historica. 14: 448. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-04-16. Retrieved 2018-06-22.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Duncan, Pamela (2017-07-27). "Gay relationships are still criminalised in 72 countries, report finds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-02-02.

- ^ "Is Beheading Really the Punishment for Homosexuality in Saudi Arabia?". Archived from the original on 2003-02-07.

- ^ 2011 Report on State-sponsored Homophobia Archived 2011-12-19 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Sudan drops death penalty for homosexuality". Erasing 76 Crimes. July 15, 2020. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ottosson, Daniel (May 2010). "State-sponsored Homophobia: A world survey of laws prohibiting same sex activity between consenting adults" (PDF). International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 22, 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Jamaica: Homophobia and hate crime is rife". Belfast Telegraph. September 12, 2009.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Funkeson, Kristina (August 9, 2007). "Dancehall star signs Reggae Compassionate Act". Freemuse. Archived from the original on January 21, 2012.

- ^ Padgett, Tim (April 12, 2006). "The Most Homophobic Place on Earth?". Time. Archived from the original on June 19, 2006.

- ^ "Love, Hate, and the Law: Decriminalizing Homosexuality". Amnesty International. July 4, 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ "Burundi: Repeal Law Criminalizing Homosexual Conduct - Human Rights Watch". Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "United Nations: General assembly to address sexual orientation and gender identity – Statement affirms promise of Universal Declaration of Human Rights" (Press release). Amnesty International. 12 December 2008. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ "UN: General Assembly statement affirms rights for all" (Press release). Amnesty International. 12 December 2008. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ Pleming, Sue (18 March 2009). "In turnaround, U.S. signs U.N. gay rights document". Reuters. Retrieved 20 March 2009.

- ^ "Número de assassinatos de gays no país cresceu 62% desde 2007, mas tema fica fora da campanha - Jornal O Globo". Oglobo.globo.com. Retrieved 2012-08-14.

- ^ "Violent deaths of LGBT people in Brazil hit all-time high". The Guardian. 22 January 2018.

- ^ Gay-Bashing Murders Up 55 Percent Archived 2010-10-30 at the Wayback Machine (ipsnews.net, 22 April 2009)

- ^ UM VERMELHO-E-AZUL PARA DISSECAR UMA NOTÍCIA. OU COMO LER UMA FARSA ESTATÍSTICA. OU AINDA: TODO BRASILEIRO MERECE SER GAY (in Portuguese). Veja. 2009. Retrieved 2011-06-27.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Altschiller, Donald (2005). Hate Crimes: a reference handbook. ABC-CLIO. pp. 26–28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Stahnke, Tad; et al. (2008). "Violence Based on Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Bias: 2008 Hate Crime Survey" (PDF). Human Rights First. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 27, 2010.

- ^ "Hate Crime Statistics: Offense Type by Bias Motivation". Federal Bureau of Investigation. 2008.

- ^ Suri, Manveena (28 May 2018). "Indian mob kills transgender woman over fake rumors spread on WhatsApp". CNN. Retrieved 28 May 2018.

- ^ Waling, Andrea; Roffee, James A (2018-03-30). "Supporting LGBTIQ+ students in higher education in Australia: Diversity, inclusion and visibility". Health Education Journal. 77 (6): 667–679. doi:10.1177/0017896918762233. ISSN 0017-8969. S2CID 80302675.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Pérez, Zenen Jaimes; Hussey, Hannah (2014-09-19). A Hidden Crisis: Including the LGBT Community When Addressing Sexual Violence on College Campuses. Center for American Progress.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hill, Catherine; Silva, Elena (2005). Drawing the Line: Sexual Harassment on Campus. American Association of University Women Educational Foundation, 1111 Sixteenth St. ISBN 9781879922358.

- ^ Bello, Barbara Giovanna (2011). "Hate Crimes". In Stange, Mary Zeiss; Oyster, Carol K.; Sloan, Jane E. (eds.). Encyclopedia of Women in Today's World, Volume 1. SAGE. pp. 662–665. ISBN 9781412976855. Retrieved 22 February 2018.

- ^ Geen, Jessica (November 18, 2010). "UN deletes gay reference from anti-execution measures". Pink News.

- ^ "U.N. panel cuts gay reference from violence measure". U.S. Daily. November 17, 2010. Archived from the original on 2016-06-03. Retrieved 2018-12-11.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Gay community troubled by release of killer in Stanley Park death". CBC News. 5 February 2009. Retrieved 13 September 2010.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Stryker, Jeff (23 October 1998). "Asking for it". Salon Magazine.

- ^ Lee, Cynthia (2003). Murder and the Reasonable Man: Passion and Fear in the Criminal Courtroom. NYU Press. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-8147-5115-2.

- ^ Taylor, Christian (May 12, 2008). "Gay Pride Parade Trapped on Bus". SameSame. Archived from the original on October 28, 2009.

- ^ 67 GenderDoc-M (May 11, 2008). "Moldovan Gay Pride Threatened, Cops Refuse Protection for Marchers".

- ^ Ireland, Doug (May 17, 2007). "Moscow Pride Banned Again". UK Gay News. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016.

- ^ "We Have the Upper Hand: Freedom of assembly in Russia and the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people". Human Rights Watch and ILGA-Europe. June 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-12-02.

- ^ Peto, Sandor and Krisztina Than (July 6, 2008). "Anti-gay violence mars Hungarian parade". The Star Online. Archived from the original on October 14, 2012.

- ^ Bos, Stefan (July 6, 2008). "Violent Protests Disrupt Hungary's Gay Rights Parade". VOA News. Archived from the original on August 2, 2008.

- ^ Hunter, George. "Detroit chief: Nazis wanted 'Charlottesville 2.0' at Detroit gay pride event". Detroit News. Retrieved 2019-08-14.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Why 'LGBT-free zones' are on the rise in Poland, Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 27 July 2019

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Anti-Gay Brutality in a Polish Town Blamed on Poisonous Propaganda, New York Times, 27 July 2019

- ^ Jump up to: a b Polish city holds first LGBTQ pride parade despite far-right violence, CNN, 21 July 2019

- ^ Archbishop claims a ‘rainbow plague’ is afflicting Poland, Pink News, 2 August 2019

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Homophobia and Hip-Hop". PBS. Retrieved 2009-03-30.

- ^ "Coalition seeks ejection of reggae stars over anti-gay lyrics". CBC News. September 25, 2007.

- ^ Grew, Tony (October 9, 2008). "Immigration minister criticised for letting homophobic artist into Canada". Pink News. Archived from the original on January 2, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ Pursell, Robert (January 31, 2018). "How L.A. Punks of the '80s and the '90s Kept Neo-Nazis Out of Their Scene". Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ Nancy J. Chodorow. Statement in a public forum on homophobia by The American Psychoanalytic Foundation, 1999

- ^ "Masculinity Challenged, Men Prefer War and SUVs". LiveScience.com. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ "Fans' culture hard to change". Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Franklin, Karen (April 2004). "Enacting Masculinity: Antigay Violence and Group Rape as Participatory Theater". Sexuality Research & Social Policy. Springer Verlag. 1 (2): 25–40. doi:10.1525/srsp.2004.1.2.25. S2CID 143439942. Retrieved 8 July 2020 – via ResearchGate.

- ^ West, D.J. Homosexuality re-examined. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1977. ISBN 0-8166-0812-1

- ^ Leviticus 18:22

- ^ Leviticus 20:13

- ^ Candace Chellew-Hodge. "The "Gay" Princess Di Bible". Religion Dispatches. Retrieved 14 June 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Human Sexuality". The United Methodist Church. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ Catechism of the Catholic Church (2nd ed.). Libreria Editrice Vaticana. 2019. Paragraph 2357.

- ^ "Criteria for the Discernment of Vocation for Persons with Homosexual Tendencies". www.vatican.va. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Holy Synod - Encyclicals - Synodal Affirmations on Marriage, Family, Sexuality, and the Sanctity of Life". www.oca.org. Retrieved May 30, 2020.

- ^ "Stances of Faiths on LGBT Issues: African Methodist Episcopal Church". The Human Rights Campaign. Archived from the original on 2009-11-21. Retrieved 2009-11-25.

- ^ "The Christian Life - Christian Conduct". Free Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 2008-05-13. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ "British Methodists reject blessing of same-sex relationships". The United Methodist Church. Archived from the original on 2016-09-14. Retrieved 2007-05-16.

- ^ "Summaries of General Synod Discussions and Actions on Homosexuality and the Rights of Homosexuals". Reformed Church in America. Archived from the original on 2012-07-16. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ "We Are American Baptists". American Baptist Churches USA. Archived from the original on 2009-09-02. Retrieved 2009-11-21.

- ^ "Evangelical Alliance (UK): Faith, Hope and Homosexuality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-08. Retrieved 2011-10-26.

- ^ "Position Statements/Sexuality". Archived from the original on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2010-11-04.

- ^ "Statement on Homosexuality". Archived from the original on 2011-08-25.

- ^ "Position Paper on Homosexuality". Archived from the original on 2010-09-21.

- ^ "Homosexuality" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-12.

- ^ "Homosexuality—How Can I Avoid It?". Awake!: 28–30. February 2007.

- ^ "Interview with Elder Dallin H. Oaks and Elder Lance B. Wickman: "Same-Gender Attraction"". The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. Retrieved April 5, 2021.

- ^ "Exodus International Policy Statements". Exodus International. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2007.

- ^ Tenety, Elizabeth, "Exodus International, criticized for ‘reparative therapies’ for gay Christians, to shut down", Washington Post, June 20, 2013. Included link to video of Chambers' talk at Exodus' website Archived 2013-06-22 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 2013-06-20.

- ^ Snow, Justin (June 20, 2013). "'Ex-gay' ministry apologizes to LGBT community, shuts down". MetroWeekly. Archived from the original on June 24, 2013. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Newcomb, Alyssa (June 20, 2013). "Exodus International: 'Gay Cure' Group Leader Shutting Down Ministry After Change of Heart". ABC News. Retrieved June 20, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Just the Facts About Sexual Orientation & Youth: A Primer for Principals, Educators and School Personnel". American Academy of Pediatrics, American Counseling Association, American Association of School Administrators, American Federation of Teachers, American Psychological Association, American School Health Association, The Interfaith Alliance, National Association of School Psychologists, National Association of Social Workers, National Education Association. 1999. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ H., K. (15 January 1999). "APA Maintains Reparative Therapy Not Effective". Psychiatric News (news division of the American Psychiatric Association). Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Luo, Michael (12 February 2007). "Some Tormented by Homosexuality Look to a Controversial Therapy". The New York Times. p. 1. Retrieved 2007-08-28.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Naughton, Philippe (December 23, 2008). "Pope accused of stoking homophobia after he equates homosexuality to climate change". The Times.

- ^ "The Roman Catholic Church and Homosexuality Statements and events prior to 1997". Religious Tolerance. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Some Considerations Concerning the Catholic Response to Legislative Proposals on the Non-Discrimination of Homosexual Persons", Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith. July 1992.

- ^ "Pastoral provision at the Church of Our Lady of the Assumption". Diocese of Westminster. 28 February 2012. Retrieved July 16, 2018.

- ^ Gallagher, Delia (2018-05-21). "Pope Francis tells gay man: 'God made you like that'". CNN. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ "Pope Francis tells gay man: 'God made you like this' | World news". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ Emma Sarran Webster (2018-05-21). "Pope Francis Reportedly Told a Gay Man "God Made You Like This"". Teen Vogue. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ "LGBT community cheers Pope Francis' 'God made you like this' remark". America Magazine. 2018-05-21. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Homosexuality and Lesbianism: Sexual Perversions". IslamOnline. Archived from the original on 2010-06-03.

- ^ Rough Guide to South East Asia: Third Edition. Rough Guides Ltd. August 2005. p. 74. ISBN 1-84353-437-1.

- ^ Bosworth, Ed. C. and E. van Donzel (1983). The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Leiden.

- ^ Wafer, Jim (1997). Muhammad and Male Homosexuality. New York University Press. p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8147-7468-7. Retrieved 2010-07-24.

- ^ Dynes, Wayne (1990). Encyclopaedia of Homosexuality. New York.

- ^ "Homosexuality prohibited in Submission (Islam)". www.masjidtucson.org. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- ^ Grew, Tony (September 1, 2008). "Violence against gays preached in British mosques claims new documentary". Pink News. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ The punishment for homosexuality Archived 2013-09-21 at the Wayback Machine

Islam Q&A, Fatwa No. 38622 - ^ "Eleventh Greater sin: Sodomy". Al-Islam.org. Retrieved 2017-03-05.

- ^ Stack, Liam (June 13, 2016). "Before Orlando Shooting, an Anti-Gay Massacre in New Orleans Was Largely Forgotten". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

The terrorist attack ... was the largest mass killing of gay people in American history, but before Sunday that grim distinction was held by a largely forgotten arson at a New Orleans bar in 1973 that killed 32 people at a time of pernicious anti-gay stigma.

- ^ Ingraham, Christopher (June 12, 2016). "In the modern history of mass shootings in America, Orlando is the deadliest". Washington Post.

- ^ Peralta, Eyder (June 13, 2016). "Putting 'Deadliest Mass Shooting In U.S. History' Into Some Historical Context". NPR.

- ^ "Orlando Gunman Was 'Cool and Calm' After Massacre, Police Say". NY Times.

- ^ McBride, Brian; Edison Hayden, Michael (June 15, 2016). "Orlando Gay Nightclub Massacre a Hate Crime and Act of Terror, FBI Says". ABC News. Retrieved June 17, 2016.

- ^ Santora, Marc (June 12, 2016). "Last Call at Pulse Nightclub, and Then Shots Rang Out". The New York Times. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

External links[]

- Violence against LGBT people