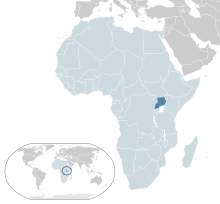

LGBT rights in Uganda

LGBT rights in Uganda | |

|---|---|

| |

| Status | Illegal since British introduced anti-sodomy laws of Penal Code Act of 1950 |

| Penalty | Up to life imprisonment for "carnal knowledge against the order of nature". 7 years imprisonment for "gross indecency". Vigilante torture, beatings, and executions are common [1][2][3] |

| Gender identity | No |

| Military | No |

| Discrimination protections | None |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | No recognition of same-sex unions |

| Restrictions | Same-sex marriage constitutionally banned since 2005 |

| Adoption | No |

Both male and female homosexual activity is illegal in Uganda. Under the Penal Code, "carnal knowledge against the order of nature" between two males carries a potential penalty of life imprisonment.

The Uganda Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2014 was passed in 2013 and annulled in 2014. The Act carried a punishment of life in prison for "aggravated homosexuality".[4] The law brought Uganda into the international spotlight, and caused international outrage, with many governments refusing to provide further aid to Uganda.[5]

LGBT people continue to face major discrimination in Uganda, actively encouraged by political and religious leaders.[6][7][3] Violent and brutal attacks against LGBT people are common, often performed by state officials. Households headed by same-sex couples are not eligible for the same legal protections available to opposite-sex couples. Same-sex marriage has been constitutionally banned since 2005.

Homosexual relations were accepted and commonplace in pre-colonial Ugandan society.[8][9] The British Empire introduced laws punishing homosexuality when Uganda became a British colony. These laws were kept after independence.[8] In May 2021, the outgoing parliament passed further criminalization laws on both sex work and gay sex.

History[]

Similarly to neighbouring Kenya, Rwanda and Burundi, male homosexual relations were quite common in pre-colonial Ugandan society. Among the Baganda, Uganda's largest ethnic group, homosexuality was usually treated with indifference. King Mwanga II of Buganda was famously bisexual, known to have regular sexual relations with women, having had a total of 16 wives, as well as his male subjects who he abused without their consent. During his reign, he increasingly regarded the Christian missionaries and the European colonial powers, notably the British, as threats.[10]

Mwanga II took a more aggressive approach than other African leaders, choosing to expel all missionaries and insist that Christian and Muslim converts abandon their faith or face death. The Luganda term abasiyazi refers to homosexuals, though usage nowadays is commonly pejorative. The Baganda were not the only ethnic group known to engage in homosexual acts. Among the Lango people, mudoko dako individuals were believed to form a "third gender" alongside male and female. The mudoko dako were effeminate men, mostly treated by Langi society as women and could marry other men without social sanctions.[10] Homosexuality was also acknowledged among the Teso, Bahima, Banyoro, and Karamojong peoples.[11] Societal acceptance disappeared after the arrival of the British and the creation of the Uganda Protectorate.[12][8]

Presently, there is widespread denial that homosexuality was practised before colonisation. Furthermore, the false belief that homosexuality is "un-African" or "Western" is quite prevalent in Ugandan society.[8]

The term kuchu, of Swahili origin, is increasingly used by the Ugandan LGBT community. A documentary film, Call Me Kuchu, was released in 2012, focusing in part on the 2011 murder of LGBT activist David Kato.

Legal rights[]

Laws prohibiting same-sex sexual acts were first put in place under British colonial rule in the 19th century. Those laws were enshrined in the Penal Code Act 1950 and retained following independence. The following sections of that Act are relevant:

Section 145. Unnatural offences. Any person who—

- (a) has carnal knowledge of any person against the order of nature; [or]

- (b) has carnal knowledge of an animal; or

- (c) permits a male person to have carnal knowledge of him or her against the order of nature,

commits an offence and is liable to imprisonment for life.[13][14]

Section 146. Attempt to commit unnatural offences. Any person who attempts to commit any of the offences specified in section 145 commits a felony and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.[13][14]

Section 148. Indecent practices. Any person who, whether in public or in private, commits any act of gross indecency with another person or procures another person to commit any act of gross indecency with him or her or attempts to procure the commission of any such act by any person with himself or herself or with another person, whether in public or in private, commits an offence and is liable to imprisonment for seven years.[13][14]

Before the Penal Code Amendment (Gender References) Act 2000 was enacted, only same-sex acts between men were criminalized. In 2000, that Act was passed and changed references to "any male" to "any person" so that grossly indecent acts between women were criminalized as well, and are now punishable by up to seven years imprisonment. The Act also extended this criminalizing such acts to both homosexuals and heterosexuals. This effectively outlawed both oral sex and anal sex, regardless of sexual orientation, under the Penal Code.[13][14]

Anti-Homosexuality Act[]

On 13 October 2009, Member of Parliament David Bahati introduced the Anti-Homosexuality Act, 2009, which would broaden the criminalization of same-sex relationships in Uganda and introduce the death penalty for serial offenders, HIV-positive people who engage in sexual activity with people of the same sex, and persons who engage in same-sex sexual acts with people under 18 years of age. Individuals or companies that promote LGBT rights would be fined or imprisoned, or both. Persons "in authority" would be required to report any offence under the Act within 24 hours or face up to three years' imprisonment.

In November 2012, Parliament Speaker Rebecca Kadaga promised to pass a revised anti-homosexuality law in December 2012. "Ugandans want that law as a Christmas gift. They have asked for it, and we'll give them that gift."[15][16] The Parliament, however, adjourned in December 2012 without acting on the bill.[17] The bill passed on 17 December 2013 with a punishment of life in prison instead of the death penalty for "aggravated homosexuality",[4] and the new law was promulgated in February 2014.[18]

In June 2014, in response to the passing of this Act, the American State Department announced several sanctions, including, among others, cuts to funding, blocking certain Ugandan officials from entering the country, cancelling aviation exercises in Uganda and supporting Ugandan LGBT NGOs.[19]

In August 2014, Uganda's Constitutional Court annulled this law on a technicality because not enough lawmakers were present to vote.[18]

Constitutional provisions[]

Article 21 of the Ugandan Constitution, "Equality and freedom from discrimination", guarantees protection against discriminatory legislation for all citizens. It may be that because existing criminal law addresses sodomy (oral and anal sex), and applies to all genders, that it may not be in violation of Article 21, unlike the Anti-Homosexuality Act.[20]

On 22 December 2008, the ruled that Articles 23, 24, and 27 of the Uganda Constitution apply to all people, regardless of their sexual orientation or gender identity or expression. Article 23 states that "No person shall be deprived of personal liberty." Article 24 states that "No person shall be subjected to any form of torture, cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment." Article 27 states that "No person shall be subjected to: (a) unlawful search of the person, home or other property of that person; or (b) unlawful entry by others of the premises of that person or property. No person shall be subjected to interference with the privacy of that person's home, correspondence, communication or other property."[21]

In November 2016, the Constitutional Court of Uganda ruled that a provision in the Equal Opportunities Commission Act was unconstitutional. This provision effectively barred the commission from investigating "any matter involving behaviour which is considered to be immoral and socially harmful, or unacceptable by the majority of the cultural and social communities in Uganda." The court ruled that the section breaches the right to a fair hearing and as well as the rights of minorities, as guaranteed in the Constitution.[22]

The court also ruled that Uganda's Parliament cannot create a class of "social misfits who are referred to as immoral, harmful and unacceptable" and cannot legislate the discrimination of such persons.[22] Following the ruling, Maria Burnett, Human Rights Watch Associate Director for East Africa, said: "Because of their work, all Ugandans should now be able to bring cases of discrimination – against their employers who fired or harassed them, or landlords who kicked them out of their homes – and finally receive a fair hearing before the commission."

Recognition of same-sex relationships[]

On 29 September 2005, President Yoweri Museveni signed a constitutional amendment prohibiting same-sex marriage.[23] Clause 2a of Section 31 states: "Marriage between persons of the same sex is prohibited."[24]

Recognition of transgender identity[]

In October 2021, trans woman Cleopatra Kambugu Kentaro was issued new ID identifying her as female. She is the first Ugandan to have a change of gender legally recognized.[25]

Further 2021 criminalization laws[]

In May 2021, the outgoing parliament passed a bill further criminalizing sex work and gay sex in the final days of its last session.[26][27] However, the incoming government has stated that it will not grant assent to the bill, meaning that it will not become law.[28] On 29 July 2021, however, petitions by gay and human rights activists arose to President Museveni not to sign another bill into law, which would further criminalize gay sex, stating that it could increase violent attacks even to people suspected of being gay.[29]

Summary table[]

| Same-sex sexual activity legal | |

| Equal age of consent | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in employment only | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in the provision of goods and services | |

| Anti-discrimination laws in all other areas (Incl. indirect discrimination, hate speech) | |

| Same-sex marriages | |

| Recognition of same-sex couples | |

| Stepchild adoption by same-sex couples | |

| Joint adoption by same-sex couples | |

| LGBT people allowed to serve openly in the military | |

| Right to change legal gender | |

| Access to IVF for lesbians | |

| Commercial surrogacy for gay male couples | |

| MSMs allowed to donate blood |

Living conditions[]

In 2004, the Uganda Broadcasting Council fined Radio Simba over $1,000 and forced it to issue a public apology after hosting homosexuals on a live talk show. The council's chairman, Godfrey Mutabazi, said the programme "is contrary to public morality and is not in compliance with the existing law". Information Minister Nsaba Buturo said the measure reflected Ugandans' wish to uphold "God's moral values" and "We are not going to give them the opportunity to recruit others."[30]

In 2005, Human Rights Watch reported on Uganda's abstinence until marriage programs. "By definition, ... [they] discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. For young people who are lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender ... and cannot legally marry in Uganda ..., these messages imply, wrongly, that there is no safe way for them to have sex. They deny these people information that could save their lives. They also convey a message about the intrinsic wrongfulness of homosexual conduct that reinforces existing social stigma and prejudice to potentially devastating effect."[31]

In June 2012, the Ugandan Government announced the ban of 38 non-governmental organizations (NGO) it accused of "promoting homosexuality" and "undermining the national culture". Simon Lokodo, the country's Minister of Ethics and Integrity, claimed the NGOs were "receiving support from abroad for Uganda's homosexuals and 'recruiting' young children into homosexuality." He also said that "they are encouraging homosexuality as if it is the best form of sexual behaviour."[32] That same month, Lokodo ordered Ugandan police to break-up an LGBT rights workshop in Kampala.[33] Later in the month, the Ugandan Government, in an apparent rebuke of Lokodo, announced that it will no longer attempt to break up meetings of LGBT rights groups.[34]

The U.S. Department of State's 2011 human rights report found that:[35]

LGBT persons faced discrimination and legal restrictions. It is illegal to engage in homosexual acts.... While no persons were convicted under the law [in 2011], the government arrested persons for related offenses. For example, in July police arrested an individual for "attempting" to engage in homosexual activities. On July 15, [2011,] a court in Entebbe charged him with "indecent practices" and released him on bail. Hearing of the case was pending at year's end.

LGBT persons were subject to societal harassment, discrimination, intimidation, and threats to their well-being [in 2011] and were denied access to health services. Discriminatory practices also prevented local LBGT NGOs from registering with the NGO Board and obtaining official NGO status....

On January 26, [2011,] LGBT activist David Kato, who had successfully sued the local tabloid discussed above for the 2010 publication of his picture under the headline "Hang Them," was bludgeoned to death at his home outside Kampala. On February 2, police arrested Sidney Enock Nsubuga for Kato's murder. On November 9, Nsubuga pled guilty and was sentenced to 30 years' imprisonment.

On October 3, [2011,] the Constitutional Court heard oral arguments on a 2009 petition filed by a local human rights and LGBT activists challenging the constitutionality of Section 15(6)(d) of the Equal Opportunities Commission Act. Section 15(6)(d) prevents the Equal Opportunities Commission from investigating "any matter involving behavior which is considered to be (i) immoral and socially harmful, or (ii) unacceptable by the majority of the cultural and social communities in Uganda." The petitioner argued that this clause is discriminatory and violates the constitutional rights of minority populations. A decision was pending at year's end.

A 2018 article in African Health Sciences said that Uganda's high HIV rate has "roots" in Uganda's stigma against same-sex sexual behavior and sex work.[36]

In June 2021, a raid on the Happy Family Youth Shelter in Kampala resulted in 44 arrests, police claiming that an illegal same-sex wedding was being held and that the participants were "doing a negligent act likely to spread infection of disease."[37] Several of the detainees then alleged that police performed invasive anal examinations on them. 39 of the 44 were released on bail after several days in detention, with the trial schedule for 8 July.[38]

Outings by newspapers[]

In August 2006, a Ugandan newspaper, The Red Pepper, published a list of the first names and professions (or areas of work) of 45 allegedly gay men.[39]

In October 2010, the tabloid paper Rolling Stone published the full names, addresses, photographs, and preferred social-hangouts of 100 allegedly gay and lesbian Ugandans, accompanied by a call for their execution. David Kato, Kasha Jacqueline, and Pepe Julian Onziema, all members of the Civil Society Coalition On Human Rights and Constitutional Law, filed suit against the tabloid. A High Court judge in January 2011 issued a permanent injunction preventing Rolling Stone and its managing editor Giles Muhame from "any further publications of the identities of the persons and homes of the applicants and homosexuals generally".[40]

The court further awarded 1.5 million Ugandan shillings plus court costs to each of the plaintiffs. The judge ruled that the outing, and the accompanying incitation to violence, threatened the subjects' fundamental rights and freedoms, attacked their right to human dignity, and violated their constitutional right to privacy.[40] Kato was murdered in 2011, shortly after winning the lawsuit.[41]

LGBT rights activism[]

Despite the criminal laws and prevailing attitudes, the Government has not expressly banned Uganda residents from trying to change public policies and attitudes with regards to LGBT people.

The climate in Uganda is hostile to homosexuals; many political leaders have used openly anti-gay rhetoric, and have said that homosexuality is "akin to bestiality", was "brought to Uganda by white people" and is "un-African". Simon Lokodo, Minister for Ethics and Integrity, is known by Ugandan LGBT activists as "the country's main homophobe", has suggested that rape is more morally acceptable than consensual sex between people of the same sex, has accompanied violent police raids on LGBT events and actively suppresses freedom of speech and of assembly for LGBT people.[42]

Uganda's main LGBT rights organization is Sexual Minorities Uganda, founded in 2004 by Victor Mukasa and has been allowed to conduct its activities without much government interference. Frank Mugisha is the executive director and the winner of both the 2011 Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award and the 2011 Rafto Prize for his work on behalf of LGBT rights in Uganda.

In late 2014, LGBT Ugandans published the first installment of Bombastic Magazine and launched the online platform Kuchu Times. These actions have been dubbed as a "Reclaiming The Media Campaign" by distinguished activist Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. She was awarded the Martin Ennals Award for Human Rights Defenders in 2011.[43]

Former Prime Minister Amama Mbabazi is the first Ugandan presidential candidate to openly oppose homophobia.[44] He ran in the 2016 presidential election and came third.

In August 2016, an LGBT event was brutally interrupted by police officers who violently attacked and beat the people present at the event, eventually arresting 16.[45] In August 2017, the organisers of Pride Uganda had to cancel the event after threats of arrest by the police and the Government.[42]

In November 2017, several police officers from the Kampala Metropolitan Police Area were ordered by police headquarters to attend a workshop on LGBT rights. A police spokesperson said: "What the training is aimed at, is to teach our field officers to appreciate that minorities have rights that should be respected."[46]

In October 2019, 28-year-old Ugandan LGBT activist Brian Wasswa was beaten to death in his own home.[3][47]

Public opinion[]

A 2007 Pew Global Attitudes Project poll found that 96 percent of Ugandan residents believed that homosexuality is a way of life that society should not accept, which was the fifth-highest rate of non-acceptance in the 45 countries surveyed.[48] A poll conducted in 2010, however, revealed that 11 percent of Ugandans viewed homosexual behavior as being morally acceptable. Among other members of the East African Community, only 1 percent in Tanzania, 4 percent in Rwanda, and 1 percent in Kenya had the same view. [49]

A 2013 Pew Research Center opinion survey showed that 96% of Ugandans believed homosexuality should not be accepted by society, while 4% believed it should.[50] Older people were more accepting than younger people: 3% of people between 18 and 29 believed it should be accepted, 2% of people between 30 and 49 and 7% of people over 50.

In May 2015, PlanetRomeo, an LGBT social network, published its first Gay Happiness Index (GHI). Gay men from over 120 countries were asked about how they feel about society's view on homosexuality, how do they experience the way they are treated by other people and how satisfied are they with their lives. Uganda was ranked last with a GHI score of 20.[51]

A poll carried out by ILGA found attitudes towards LGBT people had significantly changed by 2017: 49% of Ugandans agreed that gay, lesbian and bisexual people should enjoy the same rights as straight people, while 41% disagreed. Additionally, 56% agreed that they should be protected from workplace discrimination. 54% of Ugandans, however, said that people who are in same-sex relationships should be charged as criminals, while 34% disagreed. As for transgender people, 60% agreed that they should have the same rights, 62% believed they should be protected from employment discrimination and 53% believed they should be allowed to change their legal gender.[52] Additionally, according to that same poll, a third of Ugandans would try to "change" a neighbour's sexual orientation if they discovered they were gay.

See also[]

References[]

- ^ "Reports: Ugandan gay rights activist 'in intensive care' after brutal attack". 29 November 2014.

- ^ "Uganda's leading gay activist: We live in fear of violence, blackmail and extortion". 3 December 2014.

- ^ a b c d Fitzsimons, Tim (19 October 2019). "Amid 'Kill the Gays' bill uproar, Ugandan LGBTQ activist is killed". NBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Uganda MPs pass controversial anti-gay law". Al Jazeera. 21 December 2013. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ "Will LGBT Ugandans Ever Be Free? Inside the Fight for a Queer Country". Pulitzer Center. 19 November 2017. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- ^ a b "Reports: Ugandan gay rights activist 'in intensive care' after brutal attack". PinkNews - Gay news, reviews and comment from the world's most read lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans news service. 29 November 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b "Uganda's leading gay activist: We live in fear of violence, blackmail and extortion". PinkNews - Gay news, reviews and comment from the world's most read lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans news service. 3 December 2014. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ a b c d Evaristo, Bernardine (8 March 2014). "The idea that African homosexuality was a colonial import is a myth". The Guardian.

- ^ "UGANDAN DOCUMENTARY ON GAY LOVE IN PRE-COLONIAL AFRICA". ILGA. 8 June 2012. Archived from the original on 27 March 2019.

- ^ a b Tamale, Sylvia (2003). "Out of the Closet: Unveiling Sexuality Discourses in Uganda" (PDF). African Women's Development Fund.

- ^ "Are you happy or are you gay?". Gay and Lesbian Coalition of Kenya. 6 December 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Scupham-bilton, Tony (8 October 2012). "Gay in the Great Lakes of Africa". The Queerstory Files.

- ^ a b c d "THE PENAL CODE ACT" (PDF). World Intellectual Property Organization. 1950.

- ^ a b c d "THE PENAL CODE ACT" (PDF). Uganda Police Force. 1950.

- ^ "Uganda to pass anti-gay law as 'Christmas gift'". BBC News. 13 November 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Muhumuza, Rodney (12 November 2012). "Uganda's Anti-Gay Bill To Pass This Year: Official". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Okeowo, Alexis (18 December 2012). "Uganda's "Kill the Gays" Bill Back in Limbo". The New Yorker. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ a b Harding, Andrew (1 August 2014). "Uganda court annuls anti-homosexuality law". BBC News. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

- ^ Harris, Grant; Pomper, Stephen (19 June 2014). "Further U.S. Efforts to Protect Human Rights in Uganda". The White House: President Barack Obama. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Constitution of the Republic of Uganda, 1995". Uganda Legal Information Institute. 8 October 1995. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Victory for LGBTs in Uganda court case". Hivos. 22 December 2008. Archived from the original on 23 July 2012. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ a b Igual, Roberto (12 November 2016). "Major LGBT rights court victory in Uganda". MambaOnline. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Uganda: IGLHRC Condems [sic] Uganda's Targeting of Lesbians and Gay Men; Calls Ban on Same-Sex Marriage "Legislative Overkill"". OutRight Action International. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "Uganda: Constitution of the Republic of Uganda". WIPO Lex. 16 February 2006. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Somuah-Annan, Grace (11 October 2021). "Uganda officially recognizes first transgender citizen". 3news.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 14 October 2021.

- ^ "Uganda passes bill criminalising same-sex relationships and sex work". the Guardian. 5 May 2021. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ Assunção, Muri. "Uganda's parliament passes legislation to further criminalize consensual same-sex relations". nydailynews.com. Retrieved 31 May 2021.

- ^ No, Uganda is not making it illegal to be gay (again), MP Fox Odoi-Oywelowo, Al Jazeera, 2021 June 06.

- ^ Segawa, Nakisanze (29 July 2021). "Anti-Gay Legislation Sparks Controversy — and Fear". PML Daily. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ "Fine for Ugandan radio gay show". BBC News. 3 October 2004.

- ^ "The Less They Know, the Better" (PDF). Human Rights Watch. March 2005. p. 57. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Smith, David (20 June 2012). "Uganda bans 38 organisations accused of 'promoting homosexuality'". The Guardian.

- ^ Stewart, Colin (18 June 2012). "Uganda police raid LGBT rights workshop". Erasing 76 Crimes. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Stewart, Colin (22 June 2012). "In rebuke, Uganda says gays will be allowed to meet". Erasing 76 Crimes. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "UGANDA" (PDF). U.S. Department of State. pp. 26–27. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ Vithalani, Jay; Herreros-Villanueva, Marta (September 2018). "HIV Epidemiology in Uganda: survey based on age, gender, number of sexual partners and frequency of testing". African Health Sciences. 18 (3): 523–530. doi:10.4314/ahs.v18i3.8. ISSN 1680-6905. PMC 6307011. PMID 30602983.

- ^ Lang, Nico. "42 People Granted Bail Following Latest Raid Targeting Uganda's LGBTQ+ Community". them. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Dozens of queer Ugandans finally freed on bail after police 'witch hunt'". PinkNews - Gay news, reviews and comment from the world's most read lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans news service. 5 June 2021. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ^ "Ugandan 'gay' name list condemned". BBC News. 8 September 2006. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ a b "Court Affirms Rights of Ugandan Gays". Human Rights First. 4 January 2011. Retrieved 12 December 2012.

- ^ "Obituary: Uganda gay activist David Kato". bbc.co.uk. BBC. 27 January 2011. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ a b Igual, Roberto (17 August 2017). "Pride Uganda cancelled in wake of police and government threats". MambaOnline. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ "Uganda gay activist Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera hailed". BBC News. 4 May 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

- ^ "Uganda has its first presidential candidate who opposes homophobia". Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ Igual, Roberto (6 August 2016). "Rest of Uganda Pride postponed following brutal police crackdown". MambaOnline. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Igual, Roberto (17 November 2017). "Uganda | Surprise as police trained to protect LGBT people". MambaOnline. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ Giardina, Henry (14 May 2021). "Ugandan LGBTQ+ activist speaks out: "every day you leave your home and aren't certain if you'll make it back"". INTO. Retrieved 17 May 2021.

- ^ ""Pew Global Attitudes Project", (pages 35, 85, and 117)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2009.

- ^ "Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa" (PDF). The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. 15 April 2010. p. 276. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 January 2013. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

- ^ "The Global Divide on Homosexuality". Pew Research Center: Global Attitudes & Trends. 4 June 2013. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ "Gay Happiness Index". ROMEO. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ^ ILGA-RIWI Global Attitudes Survey ILGA, October 2017

External links[]

- Statement of Vice President of Integrity Uganda, an Episcopal LGBT rights group. Summary of issues facing LGBT people in Uganda

- Ugandan media, politicians campaign against homosexuality. Carolyn Dunn, CBC News, last updated 26 Nov 2010.

- Anti-Gay Fervor in Uganda Tied to Right-Wing US Evangelicals – video report by Democracy Now!

- Exporting Homophobia: American far-right conservative churches establish influence on anti-gay policy in Africa Gay Ugandans face daily fear for their lives (Boise Weekly Feature – 8 Sep 2010)

- "US Religious Right Behind Ugandas Anti-Gay Law Video Rev. Kapya Kaoma

- Slouching toward Kampala/ "History of Uganda's Anti Gay Bill and The American Religious Right Involvement"

- LGBT rights in Uganda