Same-sex marriage

Legal status of same-sex unions |

|---|

|

LGBT portal |

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

|

|

|

Same-sex marriage, also known as gay marriage or homosexual marriage, is the marriage of two people of the same sex or gender, entered into in a civil or religious ceremony. There are records of same-sex marriage dating back to the first century. In the modern era, marriage equality was first granted to same-sex couples in the Netherlands on 1 April 2001.

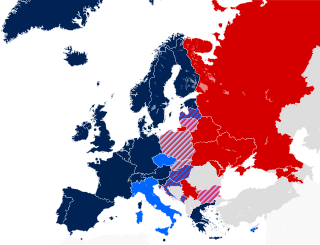

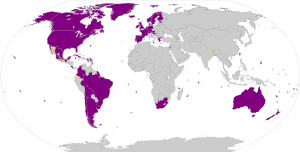

As of 2021, same-sex marriage is legally performed and recognized in 29 countries (nationwide or in some jurisdictions) with the most recent being Costa Rica (2020). In contrast, 33 countries (as of 2021) have gendered definitions of marriage in their constitutions that prevent same-sex marriage, most enacted in recent decades as a preventative measure. Some other countries have constitutionally mandated Islamic law, which is generally interpreted as prohibiting same-sex marriage. In half a dozen of the former and most of the latter, homosexuality itself is criminalized.

The application of marriage law equally to same-sex and opposite-sex couples (called marriage equality) has varied by jurisdiction, and has come about through legislative change to marriage law, court rulings based on constitutional guarantees of equality, recognition that same-sex marriage is allowed by existing marriage law,[1] and by direct popular vote (via referendums and initiatives). The recognition of same-sex marriage is considered to be a human right and a civil right as well as a political, social, and religious issue.[2] The most prominent supporters of same-sex marriage are human rights and civil rights organizations as well as the medical and scientific communities, while the most prominent opponents are religious fundamentalist groups. Polls consistently show continually rising support for the recognition of same-sex marriage in all developed democracies and in some developing democracies.

Scientific studies show that the financial, psychological, and physical well-being of gay people are enhanced by marriage, and that the children of same-sex parents benefit from being raised by married same-sex couples within a marital union that is recognized by law and supported by societal institutions.[3] Social science research indicates that the exclusion of homosexuals from marriage stigmatizes and invites public discrimination against them, with research also repudiating the notion that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon restricting marriage to heterosexuals.[4][5] Same-sex marriage can provide those in committed same-sex relationships with relevant government services and make financial demands on them comparable to that required of those in opposite-sex marriages, and also gives them legal protections such as inheritance and hospital visitation rights.[6] Opposition to same-sex marriage is based on claims such as that homosexuality is unnatural and abnormal, that the recognition of same-sex unions will promote homosexuality in society, and that children are better off when raised by opposite-sex couples.[7] These claims are refuted by scientific studies, which show that homosexuality is a natural and normal variation in human sexuality, and that sexual orientation is not a choice. Many studies have shown that children of same-sex couples fare just as well as the children of opposite-sex couples; some studies have shown benefits to being raised by same-sex couples.[8]

Terminology[]

Alternative terms[]

Some proponents of the legal recognition of same-sex marriage—such as Marriage Equality USA (founded in 1998), Freedom to Marry (founded in 2003), and Canadians for Equal Marriage—have long used the terms marriage equality and equal marriage to signal that their goal was for same-sex marriage to be recognized on equal ground with opposite-sex marriage. Opponents of same-sex marriage, by contrast, characterized gay couples as seeking "special rights".[9][10][11][12][13][14][15]

The AP Stylebook recommends the usage of the phrase marriage for gays and lesbians or the term gay marriage in space-limited headlines. The Associated Press warns that the construct gay marriage can imply that the marriages of same-sex couples are somehow different from the marriages of opposite-sex couples.[16][17]

Use of the term marriage[]

Anthropologists have struggled to determine a definition of marriage that absorbs commonalities of the social construct across cultures around the world.[18][19] Many proposed definitions have been criticized for failing to recognize the existence of same-sex marriage in some cultures, including in more than 30 African cultures, such as the Kikuyu and Nuer.[19][20][21]

With several countries revising their marriage laws to recognize same-sex couples in the 21st century, all major English dictionaries have revised their definition of the word marriage to either drop gender specifications or supplement them with secondary definitions to include gender-neutral language or explicit recognition of same-sex unions.[22][23] The Oxford English Dictionary has recognized same-sex marriage since 2000.[24]

Opponents of same-sex marriage who want marriage to be restricted to pairings of a man and a woman, such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Catholic Church, and the Southern Baptist Convention, use the term traditional marriage to mean opposite-sex marriage.[25][26]

History[]

Ancient[]

A reference to same-sex marriage appears in the Sifra, which was written in the 3rd century CE. The Book of Leviticus prohibited homosexual relations, and the Hebrews were warned not to "follow the acts of the land of Egypt or the acts of the land of Canaan" (Lev. 18:22, 20:13). The Sifra clarifies what these ambiguous "acts" were, and that they included same-sex marriage: "A man would marry a man and a woman a woman, a man would marry a woman and her daughter, and a woman would be married to two men."[27]

What is arguably the first historical mention of the performance of same-sex marriages occurred during the early Roman Empire according to controversial[28] historian John Boswell.[29] These were usually reported in a critical or satirical manner.[30]

Child emperor Elagabalus referred to his chariot driver, a blond slave from Caria named Hierocles, as his husband.[31] He also married an athlete named Zoticus in a lavish public ceremony in Rome amidst the rejoicings of the citizens.[32][33][34]

The first Roman emperor to have married a man was Nero, who is reported to have married two other males on different occasions. The first was with one of Nero's own freedmen, Pythagoras, with whom Nero took the role of the bride.[35] Later, as a groom, Nero married Sporus, a young boy, to replace the adolescent female concubine he had killed[36][37] and married him in a very public ceremony with all the solemnities of matrimony, after which Sporus was forced to pretend to be the female concubine that Nero had killed and act as though they were really married.[36] A friend gave the "bride" away as required by law. The marriage was celebrated in both Greece and Rome in extravagant public ceremonies.[38]

Conubium existed only between a civis Romanus and a civis Romana (that is, between a male Roman citizen and a female Roman citizen), so that a marriage between two Roman males (or with a slave) would have no legal standing in Roman law (apart, presumably, from the arbitrary will of the emperor in the two aforementioned cases).[39] Furthermore, according to Susan Treggiari, "matrimonium was then an institution involving a mother, mater. The idea implicit in the word is that a man took a woman in marriage, in matrimonium ducere, so that he might have children by her."[40]

In 342 AD, Christian emperors Constantius II and Constans issued a law in the Theodosian Code (C. Th. 9.7.3) prohibiting same-sex marriage in Rome and ordering execution for those so married.[41] Professor Fontaine of Cornell University Classics Department has pointed out that there is not provision for same-sex marriage in Roman Law, and the text from 342 A.D. is corrupt, "marries a woman" might be "goes to bed in a dishonorable manner with a man" as a condemnation of homosexual behavior between men.[42] The Boxer Codex, dated 1590, records the normality and acceptance of same-sex marriage in the native cultures of the Philippines prior to colonization.[43]

A 17th century Chinese writer Li Yu attests same-sex marriages in China in his period.[citation needed]

Contemporary[]

Historians variously trace the beginning of the modern movement in support of same-sex marriage to anywhere from around the 1980s to the 1990s. In United States of America same sex marriage became an official request of gay rights movement after the Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights in 1987. [44][45]

In 1989, Denmark became the first country to recognize a legal relationship for same-sex couples, establishing registered partnerships, which gave those in same-sex relationships "most rights of married heterosexuals, but not the right to adopt or obtain joint custody of a child".[46] In 2001, the metropolitan Netherlands became the first country to establish same-sex marriage by law.[47] Since then, same-sex marriage has also been established by law in 28 other countries, including most of Western Europe and much of the Americas. Yet its spread has been uneven — South Africa is the only country in Africa to take the step; Taiwan is the only one in Asia.[48]

Timeline[]

Note: Dates are when marriages began to be officially certified. Same-sex marriage is still technically illegal in some polities that accept them (e.g. several Mexican states).

| 2001 |

|

|---|---|

| 2002 | |

| 2003 |

|

| 2004 |

|

| 2005 |

|

| 2006 |

|

| 2007 | |

| 2008 |

|

| 2009 |

|

| 2010 |

|

| 2011 |

|

| 2012 |

|

| 2013 |

|

| 2014 |

|

| 2015 |

|

| 2016 |

|

| 2017 |

|

| 2018 | |

| 2019 |

|

| 2020 |

|

| 2021 |

|

| TBD |

|

Same-sex marriage around the world[]

Same-sex marriage is legally performed and recognized (nationwide or in some parts) in the following countries: Argentina, Australia,[a] Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Colombia, Costa Rica, Denmark,[b] Ecuador, Finland, France,[c] Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Mexico,[d] metropolitan Netherlands,[e] metropolitan New Zealand,[f] Norway, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Taiwan, the United Kingdom,[g] the United States[h] and Uruguay.

Same-sex marriage is under consideration by the governments or the courts in Andorra,[49] Chile,[50] Cuba,[51] the Czech Republic[citation needed], Japan,[52] Liechtenstein[citation needed], various states in Mexico (e.g. Durango,[53] Sonora, Tamaulipas, Veracruz and Yucatan), Switzerland, Thailand[54] and Venezuela[citation needed]. Civil unions, as a first step toward marriage, are being considered in a number of countries, including Barbados since 2020 and Serbia in 2021.[55]

In response to the international spread of same-sex marriage, a number of countries have enacted preventative constitutional bans, with the most recent being Georgia in 2018 and Russia in 2020. In other countries, constitutions have been adopted which have wording specifying that marriage is between a man and a woman, although, especially with the older constitutions, they were not necessarily worded with the intent to ban same-sex marriage.

International court rulings[]

European Court of Human Rights[]

In 2010, the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) ruled in Schalk and Kopf v Austria, a case involving an Austrian same-sex couple who were denied the right to marry.[56] The court found, by a vote of 4 to 3, that their human rights had not been violated.[57] The court further stated that same-sex unions are not protected under art. 12 of ECHR ("Right to marry"), which exclusively protects the right to marry of opposite-sex couples (without regard if the sex of the partners is the result of birth or of sex change), but they are protected under art. 8 of ECHR ("Right to respect for private and family life") and art. 14 ("Prohibition of discrimination"). Furthermore, under European Convention of Human Rights, states are not obliged to allow same-sex marriage: [58]

The Court acknowledged that a number of Contracting States had extended marriage to same-sex partners, but went on to say that this reflected their own vision of the role of marriage in their societies and did not flow from an interpretation of the fundamental right as laid down by the Contracting States in the Convention in 1950. The Court concluded that it fell within the State’s margin of appreciation as to how to regulate the effects of the change of gender on pre-existing marriages.

— European Court of Human Rights, Schalk and Kopf v Austria[56]

British Judge Sir Nicolas Bratza, then head of the European Court of Human Rights, delivered a speech in 2012 that signaled the court was ready to declare same-sex marriage a "human right", as soon as enough countries fell into line.[59][60][61]

Article 12 of the European Convention on Human Rights states that: "Men and women of marriageable age have the right to marry and to found a family, according to the national laws governing the exercise of this right",[62] not limiting marriage to those in a heterosexual relationship. However, the ECHR stated in Schalk and Kopf v Austria that this provision was intended to limit marriage to heterosexual relationships, as it used the term "men and women" instead of "everyone".[56]

European Union[]

On 12 March 2015, the European Parliament passed a non-binding resolution encouraging EU institutions and member states to "[reflect] on the recognition of same-sex marriage or same-sex civil union as a political, social and human and civil rights issue".[63][64][65]

On 5 June 2018, the European Court of Justice ruled, in a case from Romania, that, under the specific conditions of the couple in question, married same-sex couples have the same residency rights as other married couples in an EU country, even if that country does not permit or recognize same-sex marriage.[66][67]

Inter-American Court of Human Rights[]

On 8 January 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) ruled that the American Convention on Human Rights mandates and requires the legalization of same-sex marriage. The landmark ruling was fully binding on Costa Rica and set binding precedent in the other signatory countries. The Court recommended that governments issue temporary decrees legalizing same-sex marriage until new legislation is brought in. The ruling applies to Barbados, Bolivia, Chile, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru and Suriname.

The Court said that governments "must recognize and guarantee all the rights that are derived from a family bond between people of the same sex". They also said that it was inadmissible and discriminatory for a separate legal provision to be established (such as civil unions) instead of same-sex marriage. The Court demanded that governments "guarantee access to all existing forms of domestic legal systems, including the right to marriage, in order to ensure the protection of all the rights of families formed by same-sex couples without discrimination". Recognizing the difficulty in passing such laws in countries where there is strong opposition to same-sex marriage, it recommended that governments pass temporary decrees until new legislation is brought in.[68]

The ruling has directly led to the legalization of same-sex marriage in Costa Rica and Ecuador. In the wake of the ruling, lawsuits regarding same-sex marriage have also been filed in Bolivia, Honduras,[69] Panama,[70] Paraguay (to recognize marriages performed abroad),[71] and Peru,[72] all of which are under the jurisdiction of the IACHR.

Legal recognition[]

Argentina[]

On 15 July 2010, the Argentine Senate approved a bill extending marriage rights to same-sex couples. The law came into effect on 22 July 2010 upon promulgation by the Argentine President.[73] Argentina thus became the first country in Latin America and the tenth in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. Polls showed that nearly 70% of Argentines supported giving gay people the same marital rights as heterosexuals.[74]

Australia[]

Australia became the second nation in Oceania to legalise same-sex marriage when the Australian Parliament passed a bill on 7 December 2017.[75] The bill received royal assent on 8 December, and took effect on 9 December 2017.[76][77] The law removed the ban on same-sex marriage that previously existed and followed a voluntary postal survey held from 12 September to 7 November 2017, which returned a 61.6% Yes vote for same-sex marriage.[78] The same legislation also legalised same-sex marriage in all of Australia's external territories.[77]

Austria[]

Since 1 January 2010, same-sex couples have been allowed to enter registered partnerships (Eingetragene Partnerschaft).[79]

In December 2015, the Vienna Administrative Court dismissed a case challenging the same-sex marriage ban. The plaintiffs appealed to the Constitutional Court, which struck down the ban on same-sex marriage as unconstitutional on 5 December 2017, with effect from 1 January 2019. The Court also decided that civil unions will be open for both same-sex and different-sex couples from that date onwards.[80][81]

Belgium[]

Belgium became the second country in the world to legally recognize same-sex marriages when a bill passed by the Belgian Federal Parliament took effect on 1 June 2003.[82] Originally, Belgium allowed the marriages of foreign same-sex couples only if their country of origin also allowed these unions, however legislation enacted in October 2004 permits any couple to marry if at least one of the spouses has lived in the country for a minimum of three months. A 2006 statute legalized adoption by same-sex spouses.[83]

Brazil[]

On 14 May 2013, the Justice's National Council of Brazil legalized same-sex marriage in the entire country in a 14–1 vote by issuing a ruling that orders all civil registers of the country to perform same-sex marriages and convert any existing civil union into a marriage, if the couple wish so. The ruling was published on 15 May and took effect on 16 May 2013.

Brazil's Supreme Court ruled in May 2011 that same-sex couples are legally entitled to legal recognition of stable unions (known as união estável), one of the two possible family entities in Brazilian legislation. It included almost all of the rights available to married couples in Brazil.[84]

Between mid-2011 and May 2013, same-sex couples had their cohabitation issues converted into marriages in several Brazil states with the approval of a state judge. All legal Brazilian marriages were always recognized all over Brazil.[85] This decision paved the way for future legislation on same-sex matrimonial rights. Before the nationwide legislation, the states of Alagoas, Bahia, Ceará, Espírito Santo, the Federal District, Mato Grosso do Sul, Paraíba, Paraná, Piauí, Rondônia, Santa Catarina, São Paulo, and Sergipe, as well as the city of Santa Rita do Sapucaí (MG), had already allowed same-sex marriages and several unions were converted into full marriages by state judges. In Rio de Janeiro, same-sex couples could also marry but only if local judges agreed with their request.

In March 2013, polls suggested that 47% of Brazilians supported marriage equalization and 57% supported adoption equalization for same-sex couples.[86]

Canada[]

Legal recognition of same-sex marriage in Canada followed a series of constitutional challenges based on the equality provisions of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. In the first such case, Halpern v. Canada (Attorney General), same-sex marriage ceremonies performed in Ontario on 14 January 2001 were subsequently validated when the common law, mixed-sex definition of marriage was held to be unconstitutional. Similar rulings had already legalized same-sex marriage in eight provinces and one territory when the 2005 Civil Marriage Act defined marriage throughout Canada as "the lawful union of two persons to the exclusion of all others".

Colombia[]

In February 2007, a series of rulings by the Constitutional Court meant that same-sex couples could apply for all the rights that heterosexual couples have in de facto unions (uniones de hecho).[87][88]

On 26 July 2011, the Constitutional Court of Colombia ordered the Congress to pass legislation giving same-sex couples similar rights to marriage by 20 June 2013. If such a law were not passed by then, same-sex couples would be granted these rights automatically.[89][90]

Congress failed to pass same-sex marriage legislation, but the civil registries did not begin issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples after the deadline.[91]

On 24 July 2013, a civil court judge in Bogotá declared a same-sex couple legally married, after a ruling on 11 July 2013 accepting the petition. This was the first same-sex couple married in Colombia.[92][93]

In September 2013, two civil court judges married two same-sex couples.[94] The first marriage was challenged by a conservative group, and it was initially annulled. Nevertheless, in October, a High Court (Tribunal Supremo de Bogotá) maintained the validity of that marriage.[95][96]

On 28 April 2016, the legal uncertainty around same-sex unions was resolved when the Constitutional Court ruled that same-sex couples are allowed to enter into civil marriages in the country and that judges and notaries are barred from refusing to perform same-sex weddings.[97][98][99]

Costa Rica[]

On 10 February 2016, the Constitutional Court of Costa Rica announced it would hear a case seeking to legalize same-sex marriage in Costa Rica and declare the country's same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional.[100]

In January 2018, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACHR) issued an Advisory Opinion (AO 24/17) regarding issues related to sexual orientation and gender identity, stating that the American Convention on Human Rights includes the recognition of same-sex marriage, in a case brought by the government of Costa Rica.

In the 2018 Costa Rican general election, the IACHR ruling on same-sex marriage became a prominent issue. Carlos Alvarado Quesada, who supports LGBT rights and favors the implementation of the ruling, won the election with 60.7% of the vote, defeating by wide margin Fabricio Alvarado, a vocal opponent of LGBT rights who was against the implementation of the ruling. On 8 August 2018, the Supreme Court of Costa Rica ruled that the prohibition of same-sex marriage in the Family Code is unconstitutional, giving Congress 18 months to reform the law or the prohibition will be automatically lifted. As the Congress did not act, same-sex marriage in Costa Rica became legal on 26 May 2020 in line with the court ruling.[101]

Denmark[]

On 25 May 1989, Denmark became the first country to legally recognize registered partnerships between same-sex couples. A registered partnership was the same as a civil marriage, but was not seen as marriage in the eyes of the church.[102]

On 7 June 2012, the Folketing (Danish Parliament) approved new laws regarding same-sex civil and religious marriage. These laws permit same-sex couples to get married in the Church of Denmark. The bills received royal assent on 12 June and took effect on 15 June 2012.[103]

On 26 May 2015, Greenland, one of two other constituent countries in the Realm of Denmark, unanimously passed a law legalizing same-sex marriage.[104][105] The first same-sex couple to marry in Greenland married on 1 April 2016, the day the law went into effect.[106]

On 29 April 2016, the Faroe Islands, the realm's other constituent country, passed a same-sex marriage bill.[107] The law required ratification in the Danish Parliament, which provided it on 25 April 2017.[108] The Faroese law allows civil marriages for same-sex couples and exempts the Church of the Faroe Islands from being required to officiate same-sex weddings. The law took effect on 1 July 2017.[109]

Ecuador[]

In May 2018, the Ecuador Supreme Court ruled, in a lesbian parenting case, that the 2018 IACHR ruling is fully binding on Ecuador and that the country must also implement the ruling in due course.[110] In June 2018, two family judges ruled the country's same-sex marriage ban unconstitutional.[111] However, the Civil Registry appealed the rulings, preventing their coming into force.[112]

Same sex marriage eventually took effect in Ecuador on 8 July 2019, following the Constitutional Court ruling which was made on 12 June 2019.[113]

Finland[]

Same-sex Registered partnerships have been legal in Finland since 2002.[114]

In 2010, Minister of Justice Tuija Brax said her Ministry was preparing to amend the Marriage Act to allow same-sex marriage by 2012.[115] On 27 February 2013, the bill was rejected by the Legal Affairs Committee of the Finnish Parliament on a vote of 9–8. A citizens' initiative was launched to put the issue before the Parliament of Finland.[116] The campaign collected 166,000 signatures and the initiative was presented to the Parliament in December 2013.[117] After being rejected by the Legal Affairs Committee twice,[118] it faced the first vote in the full parliament on 28 November 2014,[119] which passed the bill 105–92. The bill passed the second and final vote by 101–90 on 12 December 2014,[120] and was signed by the President on 20 February 2015.[117][121][122]

The law took effect on 1 March 2017.[123] It was the first time a citizens' initiative had been approved by the Finnish Parliament.[114]

France[]

Since November 1999, France has had a civil union scheme known as a civil solidarity pact that is open to both opposite-sex and same-sex couples.[124]

The French Government introduced a bill to legalize same-sex marriage, Bill 344, in the National Assembly on 17 November 2012. It received final approval in the National Assembly in a 331–225 vote on 23 April 2013.[125] Law No.2013-404 grants same-sex couples living in France, including foreigners provided at least one of the partners has their domicile or residence in France, the legal right to get married. The law also allows the recognition in France of same-sex couples' marriages that occurred abroad before the bill's enactment.[126]

The main right-wing opposition party UMP challenged the law in the Constitutional Council, which had one month to rule on whether the law conformed to the Constitution. On 17 May 2013, the Constitutional Council declared the bill legal in its entirety. President François Hollande signed it into law on 18 May 2013.[127]

Germany[]

Prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage, Germany was one of the first countries to legislate registered partnerships (Eingetragene Lebenspartnerschaft) for same-sex couples, which provided most of the rights of marriage. The law came into effect on 1 August 2001, and the act was progressively amended on subsequent occasions to reflect court rulings expanding the rights of registered partners.

Same-sex marriage has been legal in Germany since 1 October 2017. A bill recognizing marriages and adoption rights for same-sex couples passed the Bundestag on 30 June 2017 after Chancellor Angela Merkel stated that she would allow her CDU/CSU parliamentarians a conscience vote on such legislation, shortly after it was made a requirement for any future coalition by the SPD, the Greens and FDP.[128] The co-governing SPD consequently forced a vote on the issue together with the opposition parties.[129] The bill was signed into law by German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier on 20 July and came into effect on 1 October 2017.[130]

Iceland[]

Same-sex marriage was introduced in Iceland through legislation establishing a gender-neutral definition of marriage introduced by the Coalition Government of the Social Democratic Alliance and Left-Green Movement. The legislation was passed unanimously by the Icelandic Althing on 11 June 2010, and took effect on 27 June 2010, replacing an earlier system of registered partnerships for same-sex couples.[131][132] Prime Minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir and her partner were among the first married same-sex couples in the country.[133]

Ireland[]

Prior to the legalization of same-sex marriage, the Civil Partnership and Certain Rights and Obligations of Cohabitants Act 2010 allowed same sex couples to enter civil partnerships. The Act came into force on 1 January 2011 and gave same-sex couples rights and responsibilities similar to, but not equal to, those of civil marriage.[134]

On 22 May 2015, Ireland held a referendum that proposed to add to the Irish Constitution: "marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex." The proposal was approved with 62% of voters supporting same-sex marriage. On 29 August 2015, Irish President Michael D. Higgins signed the result of the May referendum into law,[135] which made Ireland the first country in the world to approve same-sex marriage at a nationwide referendum.[136] Same-sex marriage became formally legally recognized in Ireland on 16 November 2015.[137]

Luxembourg[]

The Parliament approved a bill to legalize same-sex marriage on 18 June 2014.[138] The law was published in the official gazette on 17 July and took effect on 1 January 2015.[139][140][141] On 15 May 2015, Prime Minister Xavier Bettel married Gauthier Destenay, with whom he had been in a civil partnership since 2010. Luxembourg thus became the first country in the European Union to have a prime minister who is in a same-sex marriage, and the second one in Europe.

Malta[]

Malta has recognized same-sex unions since April 2014, following the enactment of the Civil Unions Act, first introduced in September 2013. It established civil unions with same rights, responsibilities, and obligations as marriage, including the right of joint adoption and recognition of foreign same-sex marriage.[142] The Maltese Parliament gave final approval to the legislation on 14 April 2014 by a vote of 37 in favor and 30 abstentions. President Marie Louise Coleiro Preca signed it into law on 16 April. The first foreign same-sex marriage was registered on 29 April 2014 and the first civil union was performed on 14 June 2014.[142]

On 21 February 2017, Minister for Social Dialogue, Consumer Affairs, and Civil Liberties Helena Dalli said that she was preparing a bill to legalize same-sex marriage.[143] The bill was presented to Parliament on 5 July 2017.[144] The bill's last reading took place in Parliament on 12 July 2017, where it was approved 66–1. It was signed into law and published in the Government Gazette on 1 August 2017.[145] Malta became the 14th country in Europe to legalize same-sex marriage.[146][147]

Mexico[]

Stripes: Proportion of municipal coverage.

Same-sex couples can marry in Mexico City and in the states of Aguascalientes, Baja California, Baja California Sur, Campeche, Chiapas, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Colima, Hidalgo, Jalisco, Michoacán, Morelos, Nayarit, Nuevo León, Oaxaca, Puebla, Quintana Roo, San Luis Potosí, Sinaloa, Tlaxcala, and Yucatán as well as in some municipalities in Guerrero, Querétaro and Zacatecas. In individual cases, same-sex couples have been given judicial approval to marry in all other states. Since August 2010, same-sex marriages performed within Mexico are recognized by the 31 states without exception. On 18 December 2019, the ruling party, Morena, introduced a constitutional amendment that would legalize marriage at the federal level and require all states to adjust their laws correspondingly.[148]

On 21 December 2009, the Legislative Assembly of Mexico City (formerly the Federal District of Mexico City) legalized same-sex marriages and adoption by same-sex couples. The law was enacted eight days later and became effective in early March 2010.[149] On 10 August 2010, the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that while not every state must grant same-sex marriages, they must all recognize those performed where they are legal.[150]

On 28 November 2011, the first two same-sex marriages occurred in Quintana Roo after it was discovered that Quintana Roo's Civil Code did not explicitly prohibit same-sex marriage,[151] but these marriages were later annulled by the Governor of Quintana Roo in April 2012.[152] In May 2012, the Secretary of State of Quintana Roo reversed the annulments and allowed for future same-sex marriages to be performed in the state.[153]

On 11 February 2014, the Congress of Coahuila approved adoptions by same-sex couples. A bill legalizing same-sex marriages passed on 1 September 2014, making Coahuila the first state (and second jurisdiction after Mexico City) to reform its Civil Code to allow for legal same-sex marriages.[154] It took effect on 17 September, and the first couple married on 20 September.[155]

On 12 June 2015, the Governor of Chihuahua announced that his administration would no longer oppose same-sex marriages in the state. The order was effective immediately, thus making Chihuahua the third state to legalize such unions.[156][157]

On 3 June 2015, the Supreme Court of Justice of the Nation released a "jurisprudential thesis" that found state-laws defining marriage as a union between a man and a woman unconstitutional. The ruling standardized court procedures across Mexico to authorize same-sex marriages. However, the process is still lengthy and more expensive than that for an opposite-sex marriage, as the ruling did not invalidate any state laws, meaning same-sex couples will be denied the right to wed and will have to turn to the courts for individual injunctions (Spanish: amparo). However, given the nature of the ruling, judges and courts throughout Mexico must approve any application for a same-sex marriage.[158] The official release of the thesis was on 19 June 2015, which took effect on 22 June 2015.[159] Since this ruling, a majority of states have begun allowing same-sex marriage, either through legislative change, administrative decisions, or under court orders.

Netherlands[]

The Netherlands was the first country to extend marriage laws to include same-sex couples, following the recommendation of a special commission appointed to investigate the issue in 1995. A same-sex marriage bill passed the House of Representatives and the Senate in 2000, taking effect on 1 April 2001.[160]

In the Dutch Caribbean special municipalities of Bonaire, Sint Eustatius and Saba, marriage is open to same-sex couples. A law enabling same-sex couples to marry in these municipalities passed and came into effect on 10 October 2012.[161] The Caribbean countries Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten, forming the remainder of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, do not perform same-sex marriages, but must recognize those performed in the Netherlands proper. Civil unions are available in Aruba since October 2016. A same-sex marriage bill is under consideration in the Parliament of Curaçao.

New Zealand[]

On 14 May 2012, Labour Party MP Louisa Wall stated that she would introduce a member's bill, the Marriage (Definition of Marriage) Amendment Bill, allowing same-sex couples to marry.[162] The bill was drawn from the ballot and passed the first and second readings on 29 August 2012 and 13 March 2013, respectively.[163][164] The bill received royal assent from the Governor-General on 19 April and took effect on 19 August 2013.[165][166]

New Zealand marriage law only applies to New Zealand proper and the Ross Dependency in Antarctica. New Zealand's dependent territory, Tokelau, and associated states, Cook Islands and Niue, have their own marriage laws and do not perform or recognize same-sex marriage.[167]

Norway[]

Same-sex marriage became legal in Norway on 1 January 2009 when a gender-neutral marriage bill came into effect after being passed by the Norwegian legislature, the Storting, in June 2008.[168][169] Norway became the first Scandinavian country and the sixth country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage. Gender-neutral marriage replaced Norway's previous system of registered partnerships for same-sex couples. Couples in registered partnerships are able to retain that status or convert their registered partnership to a marriage. No new registered partnerships may be created.[170]

Portugal[]

Portugal created de facto unions similar to common-law marriage for cohabiting opposite-sex partners in 1999, and extended these unions to same-sex couples in 2001. However, the 2001 extension did not allow for same-sex adoption, either jointly or of stepchildren.[171]

On 11 February 2010, Parliament approved a bill legalizing same-sex marriage. The Portuguese President promulgated the law on 8 April 2010 and the law was effective on 5 June 2010, making Portugal the eighth country to legalize nationwide same-sex marriage; however, adoption was still denied for same-sex couples.[172]

In December 2015, the Portuguese Parliament approved a bill to allow adoption rights for same-sex couples.[173][174][175] It came into effect in March 2016.

South Africa[]

Legal recognition of same-sex marriages in South Africa came about as a result of the Constitutional Court's decision in the case of Minister of Home Affairs v Fourie. The court ruled on 1 December 2005 that the existing marriage laws violated the equality clause of the Bill of Rights because they discriminated on the basis of sexual orientation. The court gave Parliament one year to rectify the inequality.

The Civil Union Act was passed by the National Assembly on 14 November 2006, by a vote of 230 to 41. It became law on 30 November 2006. South Africa became the fifth country, the first in Africa, and the second outside Europe, to legalize same-sex marriage.

Spain[]

Spain was the third country in the world to legalize same-sex marriage on 3 July 2005.[176][177]

In 2004, the nation's newly elected Socialist Government, led by President José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, began a campaign for its legalization, including the right of adoption by same-sex couples.[178] After much debate, the law permitting same-sex marriage was passed by the Cortes Generales (Spain's bicameral Parliament) on 30 June 2005. King Juan Carlos signed it on 1 July 2005.[179]

Sweden[]

Same-sex marriage in Sweden has been legal since 1 May 2009, following the adoption of a new gender-neutral law on marriage by the Swedish Parliament on 1 April 2009, making Sweden the seventh country in the world to open marriage to same-sex couples nationwide. Marriage replaced Sweden's registered partnerships for same-sex couples. Existing registered partnerships between same-sex couples remained in force with an option to convert them into marriages.[180][181] Same-sex marriages have been performed by the Church of Sweden since 2009.[182]

Taiwan[]

Taiwan is the first country in Asia where same-sex marriage is legal.[183] On 24 May 2017, the Constitutional Court ruled that same-sex couples have the right to marry, and gave the Taiwanese Government two years to amend the law to that effect. It was also ruled that if the law was not amended after two years, same-sex couples would automatically be able to register valid marriage applications in Taiwan.[184] On 17 May 2019, lawmakers in Taiwan approved a bill legalizing same-sex marriage.[185] The bill was signed by the President Tsai Ing-Wen on 22 May and came into effect on 24 May 2019.[186]

United Kingdom[]

Same-sex marriage is legal in all parts of the United Kingdom. As marriage is a devolved legislative matter, different parts of the UK legalised same-sex marriage at different times; it has been recognised and performed in England and Wales since March 2014, in Scotland since December 2014, and in Northern Ireland since January 2020.

- Legislation to allow same-sex marriage in England and Wales was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom in July 2013 and took effect on 13 March 2014. The first same-sex marriages took place on 29 March 2014.

- Legislation to allow same-sex marriage in Scotland was passed by the Scottish Parliament in February 2014 and took effect on 16 December 2014. The first same-sex marriage ceremonies for same-sex couples previously in civil partnerships occurred on 16 December. The first same-sex marriage ceremonies for couples not in civil partnerships occurred on 31 December 2014.

- Legislation to allow same-sex marriage in Northern Ireland was passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom (as the Northern Ireland Assembly was suspended) in July 2019 and took effect on 13 January 2020. The first same-sex marriage ceremony took place on 11 February 2020.

Same-sex marriage is legal in nine of the fourteen British Overseas Territories. It has been recognised in South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands since 2014, Akrotiri and Dhekelia and the British Indian Ocean Territory (for UK military personnel only) since 3 June 2014, the Pitcairn Islands since 14 May 2015, the British Antarctic Territory since 13 October 2016, Gibraltar since 15 December 2016, the Falkland Islands since 29 April 2017, Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha since 20 December 2017, and Bermuda since 23 November 2018. Civil partnerships were legalized in the Cayman Islands on 4 September 2020. An appeal by the government of Bermuda of a lower court's ruling for same-sex marriage is scheduled to be heard in February 2021.

Same-sex marriage is legal in the Crown dependencies. It has been recognised and performed in the Isle of Man since 22 July 2016, in Jersey since 1 July 2018, and in the Bailiwick of Guernsey at different times: in the jurisdiction of Guernsey since 2 May 2017, in Alderney since 14 June 2018, and in Sark since 23 April 2020.

Since 2005, same-sex couples have been allowed to enter into civil partnerships, a separate union providing the legal consequences of marriage. In 2006, the High Court rejected a legal bid by a British lesbian couple who had married in Canada to have their union recognized as a marriage in the UK rather than a civil partnership.

United States[]

Same-sex marriage in the United States expanded from one state in 2004 to all fifty states in 2015 through various state court rulings, state legislation, direct popular votes, and federal court rulings. The fifty states each have separate marriage laws, which must adhere to rulings by the Supreme Court of the United States that recognize marriage as a fundamental right that is guaranteed by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, as first established in the 1967 landmark civil rights case of Loving v. Virginia.

Civil rights campaigning in support of marriage without distinction as to sex or sexual orientation began in the 1970s.[187] In 1972, the now overturned Baker v. Nelson saw the Supreme Court of the United States decline to become involved.[188] The issue became prominent from around 1993, when the Supreme Court of Hawaii ruled in Baehr v. Lewin that it was unconstitutional under the state constitution for the state to abridge marriage on the basis of sex. That ruling led to federal and state actions to explicitly abridge marriage on the basis of sex in order to prevent the marriages of same-sex couples from being recognized by law, the most prominent of which was the 1996 federal DOMA. In 2003, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health that it was unconstitutional under the state constitution for the state to abridge marriage on the basis of sex. From 2004 through to 2015, as the tide of public opinion continued to move towards support of same-sex marriage, various state court rulings, state legislation, direct popular votes (referendums and initiatives), and federal court rulings established same-sex marriage in thirty-six of the fifty states.

In May 2011, national public support for same-sex marriage rose above 50% for the first time.[189] In June 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States struck down DOMA for violating the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution in the landmark civil rights case of United States v. Windsor, leading to federal recognition of same-sex marriage, with federal benefits for married couples connected to either the state of residence or the state in which the marriage was solemnized. In June 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in the landmark civil rights case of Obergefell v. Hodges that the fundamental right of same-sex couples to marry on the same terms and conditions as opposite-sex couples, with all the accompanying rights and responsibilities, is guaranteed by both the Due Process Clause and the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Same-sex marriage is also legal in four of the United States territories: Puerto Rico, US Virgin Islands, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. It is not legal in American Samoa, amid legal uncertainty over whether the US Constitution applies there in full.

Native American Tribal Nations also have their own same-sex marriage legislation.

The United States of America is the most populous country in the world to have established same-sex marriage nationwide.

Uruguay[]

Uruguay's Chamber of Deputies passed a bill on 12 December 2012, to extend marriage rights to same-sex couples.[190] The Senate passed the bill on 2 April 2013, but with minor amendments. On 10 April 2013, the Chamber of Deputies passed the amended bill by a two-thirds majority (71–22). The president promulgated the law on 3 May 2013 and it took effect on 5 August.[191]

National debates[]

Armenia[]

On 3 July 2017, the Ministry of Justice stated that all marriages performed abroad are valid in Armenia, including marriages between people of the same sex.[192] It's not clear if the statement has any practical effect. As of 2021, no such recognition has yet been documented.[193]

Bulgaria[]

The Bulgarian Constitution forbids the legalization of same-sex marriage, stipulating that marriage can only be between a man and a woman.

In late 2017, a Bulgarian same-sex couple, who married in the United Kingdom, filed a lawsuit in order to have their marriage recognized.[194] The Sofia Administrative Court ruled against them in January 2018.[195]

A Sofia court granted a same-sex couple the right to live in Bulgaria on 29 June 2018. The couple, an Australian woman and her French spouse, had married in France in 2016, but were denied residency in Bulgaria a year later when they attempted to move there.[196]

Chile[]

Polling shows majority support for same-sex marriage among Chileans.[197] A poll carried out in September 2015 by the pollster Cadem Plaza Pública found that 60% of Chileans supported same-sex marriage, while 36% were against it.[198]

On 10 December 2014, a group of senators from various parties, joined LGBT rights group MOVILH (Homosexual Movement of Integration and Liberation) in presenting a bill to allow same-sex marriage and adoption to Congress. MOVILH had been in talks with the Chilean Government to seek an amiable solution to the pending marriage lawsuit brought against the state before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.[199] On 17 February 2015, lawyers representing the Government and MOVILH met to discuss an amicable solution to the same-sex marriage lawsuit. The Government announced that they would drop their opposition to same-sex marriage. A formal agreement between the two parties and the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights was signed in April 2015.[200] The Chilean Government pledged to legalize same-sex marriage.

On 28 January 2015, the National Congress approved a bill recognizing civil unions for same-sex and opposite-sex couples offering some of the rights of marriage. President Michele Bachelet signed the bill on 14 April, and it came into effect on 22 October.[201][202]

In September 2016, President Bachelet stated before a United Nations General Assembly panel that the Chilean Government would submit a same-sex marriage bill to Congress in the first half of 2017.[203] A same-sex marriage bill was submitted in September 2017.[204] Parliament began discussing the bill on 27 November 2017,[205] but it failed to pass before March 2018, when a new Government was inaugurated. On 16 January 2020, the bill was approved in the Senate by a 22 to 16 vote, then headed to the constitutional committee.

The 2018 Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling regarding the legalization of same-sex marriage in countries that have ratified the American Convention on Human Rights applies to Chile.

China[]

The Marriage Law of the People's Republic of China explicitly defines marriage as the union between one man and one woman. No other form of civil union is recognized. The attitude of the Chinese Government towards homosexuality is believed to be "three nos": "No approval; no disapproval; no promotion." The Ministry of Health officially removed homosexuality from its list of mental illnesses in 2001.

Li Yinhe, a sociologist and sexologist well known in the Chinese gay community, has tried to legalize same-sex marriage several times, including during the National People's Congress in 2000 and 2004 (Legalization for Same-Sex Marriage 《中国同性婚姻合法化》 in 2000 and the Same-Sex Marriage Bill 《中国同性婚姻提案》 in 2004). According to Chinese law, 35 delegates' signatures are needed to make an issue a bill to be discussed in the Congress. Her efforts failed due to lack of support from the delegates. CPPCC National Committee spokesman Wu Jianmin when asked about Li Yinhe's proposal, said that same-sex marriage was still too "ahead of its time" for China. He argued that same-sex marriage was not recognized even in many Western countries, which are considered much more liberal in social issues than China.[206] This statement is understood as an implication that the Government may consider recognition of same-sex marriage in the long run, but not in the near future.

On 5 January 2016, a court in Changsha, southern Hunan Province, agreed to hear the lawsuit of 26-year-old Sun Wenlin filed in December 2015 against the Bureau of Civil Affairs of Furong District for its June 2015 refusal to let him marry his 36-year-old male partner, Hu Mingliang. On 13 April 2016, with hundreds of same-sex marriage supporters outside, the Changsha court ruled against Sun, who vowed to appeal, citing the importance of his case for LGBT progress in China.[207]

As of August 2019, guardianship agreements have been signed in Jiangsu (the first one was registered in Nanjing in late 2017), Hunan, Sichuan, Guangdong, Shanghai,[208] Hubei and Beijing, among others. The practice is more common among older same-sex couples or couples who have been in a relationship for several years.

Cuba[]

The Cuban Constitution prohibited same-sex marriage until February 2019. In May 2019, the Government announced that the Union of Jurists of Cuba is working on a new family code, which would address same-sex marriage.

In September 2018, following some public concerns and conservative opposition against the possibility of paving the way to legalisation of same-sex marriage in Cuba, President Miguel Díaz-Canel announced his support for same-sex marriage after he told TV Telesur that he supports "marriage between people without any restrictions."[209][210]

Czech Republic[]

Before the October 2017 election, LGBT activists started a public campaign with the aim of achieving same-sex marriage within the next four years.[211][212]

Prime Minister Andrej Babiš supports the legalization of same-sex marriage.[213] A bill to legalize same-sex marriage was introduced to the Czech Parliament in June 2018.[214] Recent opinion polls have shown that the bill is quite popular in the Czech Republic; a 2018 poll found that 75% of Czechs favored legalizing same-sex marriage.[215]

El Salvador[]

In August 2016, a lawyer in El Salvador filed a lawsuit before the country's Supreme Court asking for the nullification of Article 11 of the Family Code, which defines marriage as a heterosexual union. Labeling the law as discriminatory and explaining the lack of gendered terms used in Article 34 of the Constitution's summary of marriage, the lawsuit sought to allow same-sex couples the right to wed.[216][217] On 20 December, the Salvadoran Supreme Court rejected the lawsuit on a legal technicality.[218]

A second lawsuit against the same-sex marriage ban was filed on 11 November 2016.[219] On 17 January 2019, the Supreme Court dismissed the case on procedural grounds.[220][221]

The 2018 Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling regarding the legalization of same-sex marriage in countries that have ratified the American Convention on Human Rights applies to El Salvador.

Estonia[]

In October 2014, the Estonian legislature, the Riigikogu, approved a civil union law open to both opposite-sex and same-sex couples.[222]

Georgia[]

In 2016, a man filed a challenge against Georgia's same-sex marriage ban, arguing that while the Civil Code of Georgia states that marriage is explicitly between a man and a woman; the Constitution does not reference gender in its section on marriage.[223]

In September 2017, the Georgian Parliament approved a constitutional amendment establishing marriage as "a union between a woman and a man for the purpose of creating a family".[224] President Giorgi Margvelashvili vetoed the constitutional amendment on 9 October. Parliament overrode his veto on 13 October.[225]

India[]

As of 2017, a draft of a Uniform Civil Code that would legalize same-sex marriage has been proposed.[226]

Although same-sex couples are not legally recognized currently by any form, performing a symbolic same-sex marriage is not prohibited under Indian law either. On 6 September 2018, the Supreme Court of India decriminalized homosexuality by declaring Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code unconstitutional. In 2020, several court cases were filed seeking a right to same-sex marriage under India's various denominational and non-denominational marriage laws.

Israel[]

In 2006, Israel's High Court of Justice ruled to recognize foreign same-sex marriages for the limited purpose of registration with the Administration of Border Crossings, Population and Immigration; however, this is merely for statistical purposes and grants no state-level rights. Israel does not recognize civil marriages performed under its own jurisdiction. A bill was raised in the Knesset (Israeli Parliament) to rescind the High Court's ruling, but the Knesset did not advance the bill. A bill to legalize same-sex and interfaith civil marriages was defeated in the Knesset, 39–11, on 16 May 2012.[227]

In November 2015, the National LGBT Taskforce of Israel petitioned the Supreme Court of Israel to allow same-sex marriage in the country, arguing that the refusal of the rabbinical court to recognize same-sex marriage should not prevent civil courts from performing same-sex marriages.[228] The court handed down a ruling on 31 August 2017, determining the issue was the responsibility of the Knesset, and not the judiciary.[229]

Opinion polls have shown that Israelis overwhelmingly support recognizing same-sex unions. A 2017 opinion poll showed that 79% of the Israeli public were in favor of legalizing same-sex unions (either marriage or civil unions).[230] A 2018 poll showed that 58% of Israelis were specifically in favor of same-sex marriage.[231]

Italy[]

The cities of Bologna, Naples and Fano began recognizing same-sex marriages from other jurisdictions in July 2014,[232][233] followed by Empoli, Pordenone, Udine and Trieste in September,[234][235][236] and Florence, Piombino, Milan and Rome in October,[237][238] and by Bagheria in November.[239] The Italian Council of State annulled these marriages in October 2015.

A January 2013 Datamonitor poll found that 54.1% of respondents were in favor of same-sex marriage.[240] A May 2013 Ipsos poll found that 42% of Italians supported allowing same-sex couples to marry and adopt children.[241] An October 2014 Demos poll found that 55% of respondents were in favor of same-sex marriage, with 42% against.[242] A Pew Research Center survey showed that 59% of Italians were in favor of legalizing same-sex marriage.[243]

On 25 February 2016, the Italian Senate passed a bill allowing civil unions with 173 senators in favor and 73 against. That same bill was approved by the Chamber of Deputies on 11 May 2016 with 372 deputies in favor and 51 against.[244] The President of Italy signed the bill into law on 22 May 2016 and the law went into effect on 5 June 2016.

On 31 January 2017, the Italian Supreme Court of Cassation ruled that same-sex marriages performed abroad can be fully recognized by court order, when at least one of the two spouses is a citizen of a European Union country where same-sex marriage is legal.[245]

Japan[]

Same-sex marriage is not legal in Japan. Article 24 of the Japanese Constitution states that "Marriage shall be based only on the mutual consent of both sexes and it shall be maintained through mutual cooperation with the equal rights of husband and wife as a basis."[246] Article 24 was created to establish the equality of both sexes in marriage, in opposition to the pre-war legal situation whereby the husband/father was legally defined as the head of household and marriage require permission from the male head of the family. In 2021, the district court in Sapporo ruled that this wording requires recognition of same-sex marriage, with similar suits pending in other district courts.[247]

Since 2015, three prefectures and dozens of municipalities and have begun issuing partnership certificates to same-sex couples that offer limited rights when accessing civil services.

According to a 2021 opinion poll, 65% of Japanese people support same-sex marriage, with 22% opposing. [248]

Latvia[]

On 27 May 2016, the Constitutional Court of Latvia overturned an administrative court decision that refused an application to register a same-sex marriage in the country. A Supreme Court press spokeswoman said that the court agrees with the administrative court that current regulations do not allow for same-sex marriages to be legally performed in Latvia. However, the matter should have been considered in a context not of marriage, but of registering familial partnership. Furthermore, it would have been impossible to conclude whether the applicants' rights were violated or not unless their claim is accepted and reviewed in a proper manner.[249] The Supreme Court will now decide whether the refusal was in breach of the Latvian Constitution and the European Convention on Human Rights.

Nepal[]

In November 2008, the Supreme Court of Nepal issued final judgment on matters related to LGBT rights, which included permitting same-sex couples to marry. Same-sex marriage and protection for sexual minorities were to be included in the new Nepalese Constitution required to be completed by 31 May 2012.[250][251] However, the Legislature was unable to agree on the Constitution before the deadline and was dissolved after the Supreme Court ruled that the term could not be extended.[252] The Nepali Constitution was enacted in September 2015, but does not address same-sex marriage.

In October 2016, the Ministry of Women, Children and Social Welfare constituted a committee for the purpose of preparing a draft bill to legalize same-sex marriage.[253]

Panama[]

On 17 October 2016, a married same-sex couple filed an action of unconstitutionality seeking to recognize same-sex marriages performed abroad.[254] In early November, the case was admitted to the Supreme Court.[255] A challenge seeking to fully legalize same-sex marriage in Panama was introduced before the Supreme Court in March 2017.[256] The Supreme Court heard arguments on both cases in summer 2017.[257]

As the Supreme Court was deliberating on the two cases, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruled on 9 January 2018 that countries signatory to the American Convention on Human Rights must legalise same-sex marriage. On 16 January, the Panamanian Government welcomed the decision. Then Vice President Isabel Saint Malo, speaking on behalf of the Government, announced that the country would fully abide by the ruling. Official notices, requiring compliance with the ruling, were sent out to various governmental departments that same day.[258][259] A decision in this case is still pending.

However under the presidency of the more socially conservative Laurentino Cortizo a constitutional reform was approved by the National Assembly of Panama to ban same-sex marriage by establishing in the Constitution that marriage is between a man and a woman. The reform had to be voted again in 2020 and then submitted to referendum.[260][261][262]

Peru[]

In a ruling published on 9 January 2017, the 7th Constitutional Court of Lima ordered the RENIEC to recognize and register the marriage of a same-sex couple who had previously wed in Mexico City.[263][264] RENIEC subsequently appealed the ruling.[265]

On 14 February 2017, a bill legalizing same-sex marriage was introduced in the Peruvian Congress.[266]

The 2018 Inter-American Court of Human Rights ruling regarding the legalization of same-sex marriage in countries that have ratified the American Convention on Human Rights applies to Peru. On 11 January, the president of the Supreme Court of Peru stated that the Peruvian Government should abide by the IACHR ruling.[267]

Philippines[]

Same-sex marriages and civil unions are currently not recognized by the state, the illegal insurgent Communist Party of the Philippines performs same-sex marriages in territories under its control since 2005.[268]

In October 2016, Speaker of the House of Representatives of the Philippines Pantaleon Alvarez announced he will file a civil union bill in Congress.[269] The bill was introduced to Congress in October of the following year under the wing of the House Speaker and three other congresspersons, including Geraldine Roman, the country's first duly-elected transgender lawmaker.[270]

President Rodrigo Duterte supports the legalization of same-sex marriage.[271]

On 19 June 2018, the Supreme Court of the Philippines heard oral arguments in a case seeking to legalize same-sex marriage in the Philippines.[272] The court dismissed the case on 3 September 2019 due to "lack of standing" and "failing to raise an actual, justiciable controversy," additionally finding the plaintiff's legal team liable for indirect contempt of court for "using constitutional litigation for propaganda purposes."[273]

Romania[]

On 5 June 2018, the European Court of Justice (ECJ) ruled, in a case originating from Romania, that same-sex couples have the same residency rights as different-sex couples, when a national of an EU country gets married while resident in an EU country where same-sex marriage is legal, and the spouse is from a non-EU country.[274][275]

Initially, the case was filed with the Romanian Constitutional Court, which later decided to consult with the ECJ.[276] In line with the ECJ ruling, the Constitutional Court ruled on 18 July 2018 that the state must grant residency rights to the same-sex partners of European Union citizens.[277]

In June 2019, ACCEPT and 14 people forming seven same-sex couples have sued the Romanian state to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), asking for the legal recognition of their families in Romania.[278]

An opinion poll in 2021 found that 43% ±3% of Romanians supported some form of legal protection for same-sex couples, with 26% supporting marriage. Support was 56% and 42% among respondents 18–34 years old.[279]

Serbia[]

Same-sex partnerships are under discussion in 2021.

Slovenia[]

Slovenia recognizes registered partnerships for same-sex couples.

In December 2014, the eco-socialist United Left party introduced a bill amending the definition of marriage in the 1976 Marriage and Family Relations Act to include same-sex couples. In January 2015, the Government expressed no opposition to the bill. In February 2015, the bill was passed with 11 votes to 2. In March, the Assembly passed the final bill in a 51–28 vote. On 10 March 2015, the National Council rejected a motion to require the Assembly to vote on the bill again, in a 14–23 vote. Opponents of the bill launched a petition for a referendum and managed to collect 40,000 signatures. The Parliament then voted to block the referendum with a clarification that it would be against the Slovenian Constitution to vote on matters concerning human rights. Finally, the Constitutional Court ruled against the banning of the referendum (5–4) and the referendum was held on 20 December 2015.

In the referendum, 63.4% of the voters voted against the law, rendering Parliament's same-sex marriage act invalid.[280]

South Korea[]

In July 2015, Kim Jho Kwang-soo and his partner, Kim Seung-Hwan, filed a lawsuit seeking legal status for their marriage after their marriage registration form was rejected by the local authorities in Seoul. On 25 May 2016, a South Korean district court ruled against the couple and argued that without clear legislation a same-sex union can not be recognized as a marriage.[281] The couple quickly filed an appeal against the district court ruling. Their lawyer, Ryu Min-Hee, announced that two more same-sex couples had filed separate lawsuits in order to be allowed to wed.[282]

In December 2016, a South Korean appeals court upheld the district court ruling. The couple vowed to bring the case to the Supreme Court of South Korea.[283]

A 2017 poll found that 41% of South Koreans supported same-sex marriage, while 52% were opposed.[284] Support is significantly higher among younger people, however, with a 2014 opinion poll showing that 60% of South Koreans in their 20s supported same-sex marriage, about double that of 2010 (30.5%).[285]

Switzerland[]

Switzerland has allowed registered partnerships for same-sex couples since 1 January 2007, after a 2005 referendum. Legislation to allow same-sex marriage was introduced in 2013 and passed on 18 December 2020 by the Swiss parliament. The act will be subject to a referendum if 50,000 citizens request it within three months of its passage. Public opinion strongly supports same-sex marriage, with polls indicating support by about 80% of voters as of 2020.

Venezuela[]

In April 2016, the Supreme Court announced it would hear a lawsuit that seeks to declare Article 44 of the Civil Code unconstitutional for outlawing same-sex marriage.[286]

President Nicolás Maduro supports same-sex marriage, and has suggested that the National Assembly agree to legalize it in 2021.[287]

Vietnam[]

In Vietnam, currently only a marriage between a man and a woman is recognized. Vietnam's Ministry of Justice began seeking advice on legalizing same-sex marriage from other governmental and non-governmental organizations in April and May 2012, and planned to further discuss the issue at the National Assembly in Spring 2013.[288] However, in February 2013, the Ministry of Justice requested that the National Assembly avoid action until 2014.[289]

The Vietnamese Government abolished an administrative fine imposed on same-sex weddings in 2013.[290]

In June 2013, the National Assembly began formal debate on a proposal to establish legal recognition for same-sex marriage.[291]

On 27 May 2014, the National Assembly's Committee for Social Affairs removed the provision giving legal status and some rights to cohabiting same-sex couples from the Government's bill to amend the Law on Marriage and Family.[292][293] The bill was approved by the National Assembly on 19 June 2014.[294][295]

On 1 January 2015, the 2014 Law on Marriage and Family officially went into effect. It states that while Vietnam allows same-sex weddings, it will not offer legal recognition or protection to unions between people of the same sex.[296]

International organizations[]

The terms of employment of the staff of international organizations (not commercial) in most cases are not governed by the laws of the country where their offices are located. Agreements with the host country safeguard these organizations' impartiality.

Despite their relative independence, few organizations recognize same-sex partnerships without condition. The agencies of the United Nations recognize same-sex marriages if the country of citizenship of the employees in question recognizes the marriage.[297] In some cases, these organizations do offer a limited selection of the benefits normally provided to mixed-sex married couples to de facto partners or domestic partners of their staff, but even individuals who have entered into a mixed-sex civil union in their home country are not guaranteed full recognition of this union in all organizations. However, the World Bank does recognize domestic partners.[298]

Other arrangements[]

Civil unions[]

Civil union, civil partnership, domestic partnership, registered partnership, unregistered partnership, and unregistered cohabitation statuses offer varying legal benefits of marriage. As of 31 August 2021, countries that have an alternative form of legal recognition other than marriage on a national level are: Andorra, Chile, Croatia, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Liechtenstein, San Marino, Slovenia and Switzerland.[300][301] Poland and Slovakia offer more limited rights. On a subnational level, the Mexican state of Veracruz, and the Dutch constituent country of Aruba allow same-sex couples to access civil unions or partnerships, but restrict marriage to couples of the opposite sex. Additionally, various cities and counties in Cambodia and Japan offer same-sex couples varying levels of benefits, which include hospital visitation rights and others.

Additionally, sixteen countries that have legalized same-sex marriage still have an alternative form of legal recognition for same-sex couples, usually available to heterosexual couples as well: Argentina, Australia, Austria, Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, France, Luxembourg, Malta, the Netherlands, Portugal, South Africa, Spain, the United Kingdom and Uruguay.[302][303][304][305]

They are also available in parts of the United States (California, Colorado, Hawaii, Illinois, New Jersey, Nevada and Oregon) and Canada.[306][307]

Non-sexual same-sex marriage[]

Kenya[]

Female same-sex marriage is practiced among the Gikuyu, Nandi, Kamba, Kipsigis, and to a lesser extent neighboring peoples. About 5–10% of women are in such marriages. However, this is not seen as homosexual, but is instead a way for families without sons to keep their inheritance within the family.[308]

Nigeria[]

Among the Igbo people and probably other peoples in the south of the country, there are circumstances where a marriage between women is considered appropriate, such as when a woman has no child and her husband dies, and she takes a wife to perpetuate her inheritance and family lineage.[309]

Studies[]

The American Anthropological Association stated on 26 February 2004:

The results of more than a century of anthropological research on households, kinship relationships, and families, across cultures and through time, provide no support whatsoever for the view that either civilization or viable social orders depend upon marriage as an exclusively heterosexual institution. Rather, anthropological research supports the conclusion that a vast array of family types, including families built upon same-sex partnerships, can contribute to stable and humane societies.[310]

Research findings from 1998 to 2015 from the University of Virginia, Michigan State University, Florida State University, the University of Amsterdam, the New York State Psychiatric Institute, Stanford University, the University of California-San Francisco, the University of California-Los Angeles, Tufts University, Boston Medical Center, the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health, and independent researchers also support the findings of this study.[311][vague]

Adolescence[]

A study of nationwide data from across the United States from January 1999 to December 2015 revealed that the rate of attempted suicide among school students in grades 9–12 declined by 7% and the rate of attempted suicide among high schoolers of a minority sexual orientation in grades 9–12 declined by 14% in states that established same-sex marriage, resulting in about 134,000 fewer attempting suicide each year in the United States. The researchers took advantage of the gradual manner in which same-sex marriage was established in the United States (expanding from one state in 2004 to all fifty states in 2015) to compare the rate of attempted suicide among youth in each state over the time period studied. Once same-sex marriage was established in a particular state, the reduction in the rate of attempted suicide among youth in that state became permanent. No reduction in the rate of attempted suicide among teenage youth occurred in a particular state until that state recognized same-sex marriage.[312][313] The lead researcher of the study stated that "laws that have the greatest impact on gay adults may make gay kids feel more hopeful for the future".[314][315][316]

Parenting[]

Professional organizations of psychologists have concluded that children stand to benefit from the well-being that results when their parents' relationship is recognized and supported by society's institutions, e.g. civil marriage. For example, the Canadian Psychological Association (CPA) stated in 2006 that "parents' financial, psychological and physical well-being is enhanced by marriage and that children benefit from being raised by two parents within a legally-recognized union."[317] The CPA has stated that the stress encountered by gay and lesbian parents and their children are more likely the result of the way society treats them than because of any deficiencies in fitness to parent.[317]

The American Academy of Pediatrics concluded in 2006, in an analysis published in the journal Pediatrics:

There is ample evidence to show that children raised by same-gender parents fare as well as those raised by heterosexual parents. More than 25 years of research have documented that there is no relationship between parents' sexual orientation and any measure of a child's emotional, psychosocial, and behavioral adjustment... The rights, benefits, and protections of civil marriage can further strengthen these families.[318]

Health[]

The American Psychological Association stated in 2004: "Denial of access to marriage to same-sex couples may especially harm people who also experience discrimination based on age, race, ethnicity, disability, gender and gender identity, religion, socioeconomic status and so on." It has also averred that same-sex couples who may only enter into a civil union, as opposed to a marriage, "are denied equal access to all the benefits, rights, and privileges provided by federal law to those of married couples", which has adverse effects on the well-being of same-sex partners.[319]

As of 2006, the data of current psychological and other social science studies on same-sex marriage in comparison to mixed-sex marriage indicate that same-sex and mixed-sex relationships do not differ in their essential psychosocial dimensions; that a parent's sexual orientation is unrelated to their ability to provide a healthy and nurturing family environment; and that marriage bestows substantial psychological, social, and health benefits. Same-sex parents and carers and their children are likely to benefit in numerous ways from legal recognition of their families, and providing such recognition through marriage will bestow greater benefit than civil unions or domestic partnerships.[318][320]

In 2009, a pair of economists at Emory University tied the passage of state bans on same-sex marriage in the United States to an increase in the rates of HIV infection.[321][322] The study linked the passage of a same-sex marriage ban in a state to an increase in the annual HIV rate within that state of roughly 4 cases per 100,000 population.[323] In 2010, a Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health study examining the effects of institutional discrimination on the psychiatric health of lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) individuals found an increase in psychiatric disorders, including a more than doubling of anxiety disorders, among the LGB population living in states that instituted bans on same-sex marriage. According to the author, the study highlighted the importance of abolishing institutional forms of discrimination, including those leading to disparities in the mental health and well-being of LGB individuals. Institutional discrimination is characterized by societal-level conditions that limit the opportunities and access to resources by socially disadvantaged groups.[324][325]

Issues[]

While few societies have recognized same-sex unions as marriages, the historical and anthropological record reveals a large range of attitudes towards same-sex unions ranging from praise, through full acceptance and integration, sympathetic toleration, indifference, prohibition and discrimination, to persecution and physical annihilation.[citation needed] Opponents of same-sex marriages have argued that same-sex marriage, while doing good for the couples that participate in them and the children they are raising,[326] undermines a right of children to be raised by their biological mother and father.[327] Some supporters of same-sex marriages take the view that the government should have no role in regulating personal relationships,[328] while others argue that same-sex marriages would provide social benefits to same-sex couples.[329] The debate regarding same-sex marriages includes debate based upon social viewpoints as well as debate based on majority rules, religious convictions, economic arguments, health-related concerns, and a variety of other issues.[citation needed]

Parenting[]