Seattle SuperSonics

| Seattle SuperSonics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Conference | Western | |||

| Division | Western (1967–1970) Pacific (1970–2004) Northwest (2004–2008) | |||

| Founded | 1967 | |||

| History | Seattle SuperSonics 1967–2008 Oklahoma City Thunder 2008–present[1][2] | |||

| Arena | Seattle Center Coliseum/KeyArena at Seattle Center (1967–1978, 1985–1994, 1995–2008) Kingdome (1978–1985) Tacoma Dome (1994–1995) | |||

| Location | Seattle, Washington | |||

| Team colors | Green, gold, white[3] | |||

| Team manager | Full list | |||

| Head coach | Full list | |||

| Ownership | Sam Schulman (1967–1983) Barry Ackerley (1983–2001) Basketball Club of Seattle (Howard Schultz, Chairman) (2001–2006) Professional Basketball Club LLC (Clay Bennett, Chairman) (2006–2008) | |||

| Championships | 1 (1979) | |||

| Conference titles | 3 (1978, 1979, 1996) | |||

| Division titles | 6 (1979, 1994, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2005) | |||

| Retired numbers | 6 (1, 10, 19, 24, 32, 43) | |||

| ||||

The Seattle SuperSonics, commonly known as the Sonics, were an American professional basketball team based in Seattle. The SuperSonics played in the National Basketball Association (NBA) as a member club of the league's Western Conference Pacific and Northwest divisions from 1967 until 2008. After the 2007–08 season ended, the team relocated to Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, and now play as the Oklahoma City Thunder.

Sam Schulman owned the team from its 1967 inception until 1983. It was then owned by Barry Ackerley (1983–2001), and then Basketball Club of Seattle, headed by Starbucks chairman emeritus, former president and CEO Howard Schultz (2001–2006). On July 18, 2006, the Basketball Club of Seattle sold the SuperSonics and its Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA) sister franchise Seattle Storm to the Professional Basketball Club LLC, headed by Oklahoma City businessman Clay Bennett.[4] The sale was approved by the NBA Board of Governors on October 24, 2006, and finalized on October 31, 2006, at which point the new ownership group took control.[5][6] After failing to find public funding to construct a new arena in the Seattle area, the SuperSonics moved to Oklahoma City before the 2008–09 season, following a $45 million settlement with the city of Seattle to pay off the team's existing lease at KeyArena at Seattle Center in advance of its 2010 expiration.[7]

Home games were played at KeyArena, originally known as Seattle Center Coliseum, for 33 of the franchise's 41 seasons in Seattle.[8] In 1978, the team moved to the Kingdome, which was shared with the Seattle Mariners of Major League Baseball (MLB) and the Seattle Seahawks of the National Football League (NFL). They returned to the Coliseum full-time in 1985, moving temporarily to the Tacoma Dome in Tacoma, Washington, for the 1994–95 season while the Coliseum was renovated and rebranded as KeyArena.

The SuperSonics won the NBA championship in 1979. Overall, the franchise won three Western Conference titles: 1978, 1979, and 1996. The franchise also won six divisional titles, their last being in 2005, with five in the Pacific Division and one in the Northwest Division. Settlement terms of a lawsuit between the city of Seattle and Clay Bennett's ownership group stipulated the SuperSonics' banners, trophies, and retired jerseys remain in Seattle; the nickname, logo, and color scheme are available to any subsequent NBA team that plays at a renovated KeyArena subject to NBA approval.[9] The SuperSonics' franchise history, however, would be shared with the Thunder.[10]

Franchise history[]

Team creation[]

On December 20, 1966, Los Angeles businessmen Sam Schulman and Eugene V. Klein, who both owned the AFL's San Diego Chargers at the time, and a group of minority partners were awarded an NBA franchise for the city of Seattle. Schulman would serve as the active partner and head of team operations. He named the team "SuperSonics" after Boeing's recently awarded contract for the SST project, which was later canceled.[11] The SuperSonics were Seattle's first major league sports franchise.[12]

Beginning play on October 13, 1967, the SuperSonics were coached by Al Bianchi and featured All-Star guard Walt Hazzard and NBA All-Rookie Team members Bob Rule and Al Tucker. The expansion team stumbled out of the gates with a 144–116 loss in their first game in San Francisco against the San Francisco Warriors. The team got their first win on October 21, their third game of the season in San Diego against the San Diego Rockets in overtime 117–110, and finished the season with a 23–59 record.[13]

1968–1974: The Lenny Wilkens era[]

Hazzard was traded to the Atlanta Hawks before the start of the next season for Lenny Wilkens. Wilkens brought a strong all-around game to the SuperSonics, averaging 22.4 points, 8.2 assists, and 6.2 rebounds per game for Seattle in the 1968–69 season. Rule, meanwhile, improved on his rookie statistics with 24.0 points per game and 11.5 rebounds per game. The SuperSonics, however, only won 30 games and Bianchi was replaced by Wilkens as player/coach during the offseason.

Wilkens and Rule both represented Seattle in the 1970 NBA All-Star Game, and Wilkens led the NBA in assists during the 1969–70 season. In June 1970 the NBA owners voted 13–4 to work toward a merger with the ABA;[14] SuperSonics owner Sam Schulman, a member of the ABA–NBA merger committee in 1970, was so ardently eager to merge the leagues that he publicly announced that if the NBA did not accept the merger agreement worked out with the ABA, he would move the SuperSonics from the NBA to the ABA. Schulman also threatened to move his soon-to-be ABA team to Los Angeles to compete directly with the Lakers.[15] The Oscar Robertson suit delayed the merger, and the SuperSonics remained in Seattle. Early in the 1970–71 season, however, Rule tore his left Achilles' tendon and was lost for the rest of the season.[16]

Arrival of Spencer Haywood[]

Wilkens was named the 1971 All-Star Game MVP, but the big news of the season came when owner Sam Schulman managed to land American Basketball Association Rookie of the Year and MVP Spencer Haywood following a lengthy court battle (see Haywood v. National Basketball Assn.). The following season, the SuperSonics went on to record their first winning season at 47–35. The team, led by player-coach Wilkens and First Team forward Haywood, held a 46–27 mark on March 3, but late season injuries to starters Haywood, Dick Snyder, and Don Smith contributed to the team losing eight of its final nine games; otherwise, the 1971–72 team might have become the franchise's first playoff team.

For the 1972–73 season, Wilkens was dealt to Cleveland in a highly unpopular trade,[17] and without his leadership the SuperSonics fell to a 26–56 record. One of the few bright spots of the season was Haywood's second consecutive All-NBA First Team selection, as he averaged a SuperSonics record 29.2 points per game and collected 12.9 rebounds per game.

1974–1983: The championship years[]

The legendary Bill Russell was hired as the head coach in the following year, and in 1975 he coached the SuperSonics to the playoffs for the first time. The team, which starred Haywood, guards Fred Brown and Slick Watts, and rookie center Tommy Burleson, defeated the Detroit Pistons in a three-game mini-series before falling to the eventual champion Golden State Warriors in six games. The next season, the SuperSonics traded Haywood to New York forcing the remaining players to pick up the offensive slack. Guard Fred Brown, now in his fifth season, was selected to the 1976 NBA All-Star Game and finished fifth in the league in scoring average and free throw percentage. Burleson's game continued to strengthen, while Watts led the NBA in both assists and steals and was named to the All-NBA Defensive First Team. The SuperSonics again made the playoffs, but lost to the Phoenix Suns in six games in spite of strong performances from both Brown (28.5 ppg) and Burleson (20.8 ppg) during the series.

Russell left the SuperSonics after the 1976–77 season, and under new coach Bob Hopkins the team started the season dismally at 5–17. Lenny Wilkens was brought back to replace Hopkins, and the team's fortunes immediately turned around. The SuperSonics won 11 of their first 12 games under Wilkens, finished the season at 47–35, won the Western Conference title, and led the Washington Bullets three games to two before losing in seven games in the 1978 NBA Finals. Other than the loss of center Marvin Webster to New York, the SuperSonics roster stayed largely intact during the off-season, and in the 1978–79 season they went on to win their first division title. In the playoffs, the SuperSonics defeated the Phoenix Suns in a tough seven game conference final series to set up a rematch with the Washington Bullets in the finals. This time, the Bullets lost to the SuperSonics in five games to give Seattle its first, and only, NBA title. The championship team roster included the powerful backcourt tandem of Gus Williams and Finals MVP Dennis Johnson, second year All-Star center Jack Sikma, forwards John Johnson and Lonnie Shelton, and key reserves Fred Brown and Paul Silas.

The 1979–80 season saw the SuperSonics finish second in the Pacific Division to the Los Angeles Lakers with a strong 56–26 record. That season, the SuperSonics set an NBA record with a regular season average attendance of 21,725 fans per game (since broken).[18] Fred Brown won the NBA's first three-point shooting percentage title, Jack Sikma played in the second of his seven career All-Star Games for Seattle, Gus Williams and Dennis Johnson were both named to the All-NBA Second Team, and Johnson was also named to the All-NBA First Defensive Team for the second consecutive year. The SuperSonics made it to the Western Conference Finals for the third straight season, but lost to the Lakers in five games.

It was the last time that the backcourt of Williams and Johnson would play together in SuperSonics uniforms, as Johnson was traded to the Phoenix Suns before the start of the 1980–81 season and Williams sat out the year due to a contract dispute. As a result, the SuperSonics fell to last place in the Pacific Division with a 34–48 mark, the only time they ever finished in last place. Williams returned for the 1981–82 season, and Seattle managed respectable 52–30 and 48–34 records during the next two years.

In 1981, the SuperSonics also created the Sonics SuperChannel, the first sports subscription cable service; subscriptions were available for $120 ($1.33 a game). It shut down after the 1984-85 season.[19][20]

1983–1989: A period of decline[]

In October 1983, original team owner Sam Schulman sold the SuperSonics to Barry Ackerley, initiating a period of decline and mediocrity for the franchise. In 1984, Fred Brown retired after playing 13 productive seasons, all with Seattle. His career reflected much of the SuperSonics' history to that time because he had been on the same team roster as Rule and Wilkens during his rookie season, playing a key role on Seattle's first playoff teams, and being the team's important sixth man during the championship series years. In recognition of his many contributions to the team, Brown's number was retired in 1986. Lenny Wilkens left the organization following the 1984–85 season, and when Jack Sikma was traded after the 1985–86 season, the last remaining tie to the SuperSonics' championship team (aside from trainer Frank Furtado) had been severed.

Among the few SuperSonics highlights of second half of the 1980s were Tom Chambers' All-Star Game MVP award in 1987, Seattle's surprise appearance in the 1987 Western Conference Finals, despite posting a 39–43 regular season record during the 1986-87 season, and the performance of the power trio of Chambers, Xavier McDaniel, and Dale Ellis. In 1987–88, the three players each averaged over 20 points per game with Ellis at 25.8 ppg, McDaniel at 21.4, and Chambers at 20.4. In the 1988–89 season, with Chambers having signed with Phoenix, Ellis improved his scoring average to 27.5 points per game and finished second in the league in three-point percentage. The SuperSonics finished with a 47–35 record, and made it to the second round of the 1989 playoffs.

1989–1998: The Payton/Kemp era[]

The SuperSonics began setting a new foundation with the drafting of forward Shawn Kemp in 1989 and guard Gary Payton in 1990, and the trading of Dale Ellis and Xavier McDaniel to other teams during the 1990–91 season. It was George Karl's arrival as head coach in 1992, however, that marked a return to regular season and playoff competitiveness for the SuperSonics. With the continued improvement of Gary Payton and Shawn Kemp, the SuperSonics posted a 55–27 record in the 1992–93 season and took the Phoenix Suns to seven games in the Western Conference Finals.

The next year, 1993–94, the SuperSonics had the best record in the NBA at 63–19, but suffered a first round loss to the Denver Nuggets, becoming the first #1 seed to lose a playoff series to an 8th seed. The Sonics moved to the Tacoma Dome for the 1994–95 season while the Coliseum underwent renovations and went on to earn a second place 57–25 record. Again, the Sonics were eliminated in the first round, this time to the Los Angeles Lakers in four games. The team returned to the rebuilt Coliseum, renamed KeyArena for the 1995–96 season.

Perhaps the strongest roster the SuperSonics ever had was the 1995–96 team, which had a franchise best 64–18 record. With a deep roster of All-NBA Second Team selections Kemp and Payton, forward Detlef Schrempf, forward Sam Perkins, guard Hersey Hawkins, and guard Nate McMillan, the team reached the NBA Finals, but lost to the Michael Jordan-led Chicago Bulls in six games. Seattle continued to be a Western Conference powerhouse during the next two seasons, winning 57 games in 1996–97 and 61 games in 1997–98 for their second and third straight Pacific Division titles. At the end of the 1997–98 season long-time Sonic and defensive specialist McMillan retired, and disagreements with management led Karl to end his tenure as head coach. He was replaced by former Sonic Paul Westphal for the 1998–99 season.

1998–2008: A decade of struggles[]

The 1998–99 season saw the SuperSonics struggle. Westphal was fired, after the team started the 2000–01 season 6–9, and replaced by then-assistant coach Nate McMillan on an interim basis,[21][22] who was then retained as permanent head coach in February 2001.[23] The 2002–03 season saw All-Star Payton traded to the Milwaukee Bucks, and it also marked the end to the SuperSonics' 11-year streak of having a season with a winning percentage of at least .500, the second longest current streak in the NBA at the time.

The 2004–05 team surprised many when it won the organization's sixth division title under the leadership of Ray Allen and Rashard Lewis, winning 52 games and defeating the Sacramento Kings to advance to the 2005 Western Conference Semifinals. The Sonics would proceed to lose in 6 games to the established trio of Tony Parker, Tim Duncan, and Manu Ginóbili and the San Antonio Spurs, who subsequently defeated the Detroit Pistons in the 2005 NBA Finals. This appearance also marked the last time that this incarnation of the SuperSonics would make the playoffs. During the off-season in 2005, head coach McMillan left the Sonics to accept a high-paying position to coach the Portland Trail Blazers. After his departure, the team regressed the following season with a 35–47 record.

2007–08: Arrival of Kevin Durant[]

On May 22, 2007, the SuperSonics were awarded the 2nd pick in the 2007 NBA draft, equaling the highest draft position the team has ever held. They selected Kevin Durant from the University of Texas. On June 28, 2007, the SuperSonics traded Ray Allen and the 35th pick of the 2nd round (Glen Davis) in the 2007 NBA draft to the Boston Celtics for rights to the 5th pick Jeff Green, Wally Szczerbiak, and Delonte West. On July 11, 2007, the SuperSonics and the Orlando Magic agreed to a sign and trade for Rashard Lewis. The SuperSonics received a future second-round draft pick and a $9.5 million trade exception from the Magic. On July 20, the SuperSonics used the trade exception and a second-round draft pick to acquire Kurt Thomas and two first-round draft picks from the Phoenix Suns.[citation needed]

In 2008, morale was low at the beginning of the SuperSonics season as talks with the City of Seattle for a new arena had broken down. The Sonics had gotten a franchise player with second overall pick in the NBA draft with Durant. However, with the Allen trade the Sonics did not have much talent to surround their rookie forward, as they lost their first eight games under coach P. J. Carlesimo on the way to a 3–14 record in the first month of the season. Durant would live up to expectations, as he led all rookies in scoring at 20.3 ppg and won the Rookie of the Year. However, the Seattle SuperSonics posted a franchise worst record of 20–62. It would end up being the final season in Seattle as Bennett ended up getting the rights to move the team after settling all the legal issues with the city.[24] The Seattle SuperSonics played their last game on April 13, 2008, winning 99–95 versus the Dallas Mavericks. Throughout the game the crowd chanted "Save our Son-ics" and Durant was seen waving his hands encouragingly at the crowd.[25]

Relocation to Oklahoma City[]

From 2001 to 2006, Starbucks chairman emeritus, former president and CEO Howard Schultz was the majority owner of the team, along with 58 partners or minor owners, as part of the Basketball Club of Seattle LLP. On July 18, 2006, Schultz sold the SuperSonics and its sister team, the Women's National Basketball Association (WNBA)'s Seattle Storm, to the Professional Basketball Club LLC (PBC), a group of businessmen from Oklahoma City for $350 million.[4] The team relocated to Oklahoma City in 2008, and now plays as the Oklahoma City Thunder.

In 2006, after unsuccessful efforts to persuade Washington state government officials to provide funding to update KeyArena, the Basketball Club of Seattle LLP, led by Howard Schultz, sold the team to the Professional Basketball Club LLC (PBC), an investment group headed by Oklahoma City businessman Clay Bennett. The purchase, at US$350 million, also included the Seattle Storm WNBA franchise. Schultz sold the franchise to Bennett's group because they thought that Bennett would not move the franchise to Oklahoma City but instead keep it in Seattle. Oklahoma City Mayor Mick Cornett was quoted as saying, "I think it's presumptuous to assume that Clay Bennett and his ownership group won't own that Seattle team for a long, long time in Seattle or somewhere else. It's presumptuous to assume they're going to move that franchise to Oklahoma City," Cornett said. "I understand that people are going to say that seems to be a likely scenario, but that's just speculation."[26]

After failing to persuade local governments to fund a $500 million arena complex in the Seattle suburb of Renton, Bennett's group notified the National Basketball Association (NBA) that it intended to move the team to Oklahoma City[27] and requested arbitration with the city of Seattle to be released from the Sonics' lease with KeyArena.[28] When the request was rejected by a judge, Seattle sued Bennett's group to enforce the lease that required the team to play in KeyArena through 2010.[29]

NBA owners gave approval of a potential SuperSonics' relocation to Oklahoma City on April 18 in a 28–2 vote by the league's Board of Governors; only Mark Cuban of the Dallas Mavericks and Paul Allen of the Portland Trail Blazers voted against the move. The approval meant the Sonics would be allowed to move to Oklahoma City's Ford Center for the 2008–09 season after reaching a settlement with the city of Seattle.[30]

On July 2, 2008, a settlement was reached that allowed the team to move under certain conditions, including the ownership group's payment of $45 million to Seattle and the possibility of an additional $30 million by 2013 if a new team had not been awarded to the city. It was agreed that the SuperSonics' name would not be used by the Oklahoma City team and that the team's history would be shared between Oklahoma City and any future NBA team in Seattle.[31][8][32] The team began play as the Oklahoma City Thunder for the 2008–09 NBA season, after becoming the third NBA franchise to relocate in the past decade. The two previous teams to relocate were the Vancouver Grizzlies, which moved to Memphis, Tennessee and began play as the Memphis Grizzlies for the 2001–02 NBA season; and the Charlotte Hornets, which moved to New Orleans and began play as the New Orleans Hornets for the 2002–03 NBA season.

In months prior to the settlement, Seattle publicly released email conversations that took place within Bennett's ownership group and alleged that they indicated at least some members of the group had a desire to move the team to Oklahoma City prior to the purchase in 2006. Before that, Sonics co-owner Aubrey McClendon told The Journal Record, an Oklahoma City newspaper, that "we didn't buy the team to keep it in Seattle; we hoped to come here", although Bennett denied knowledge of this.[33] Seattle used these incidents to argue that the ownership failed to negotiate in good faith, prompting Schultz to file a lawsuit seeking to rescind the sale of the team and transfer the ownership to a court-appointed receiver.[34] The NBA claimed Schultz' lawsuit was void because Schultz signed a release forbidding himself to sue Bennett's group, but also argued that the proposal would have violated league ownership rules. Schultz dropped the case before the start of the 2008–09 NBA season.[35]

In 2009, Seattle-area filmmakers called the Seattle SuperSonics Historical Preservation Society produced a critically acclaimed documentary film titled Sonicsgate – Requiem For A Team that details the rise and demise of the Seattle SuperSonics franchise. The movie focuses on the more scandalous aspects of the team's departure from Seattle, and it won the 2010 Webby Award for 'Best Sports Film'.[36]

Possible new franchise[]

Sacramento Kings[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2017) |

In 2011, a group of investors led by Valiant Capital Management hedge fund founder Chris Hansen spoke with then-Seattle mayor Mike McGinn about the possibilities of investing in an arena in hopes of securing an NBA franchise and reviving the SuperSonics.[37] An offer was made by McGinn to Hansen to obtain ownership of KeyArena for little to no money to aid in his efforts.[38] As KeyArena was deemed unacceptable by the NBA and barely breaking even in operation, the facility would likely have needed to be leveled and a new one built on the site. Determining there were transportation concerns in the Lower Queen Anne neighborhood around the Seattle Center, Hansen declined in favor of building a new arena at another location.[citation needed]

Hansen began quietly purchasing available land near Safeco Field in Seattle's SoDo industrial neighborhood, at the southern end of what was designated a Stadium Transition Overlay District housing both Safeco Field, home of MLB's Seattle Mariners and CenturyLink Field, home of the NFL's Seattle Seahawks and MLS's Seattle Sounders. A short time later, Hansen presented to McGinn and King County Executive Dow Constantine the proposal for a basketball, hockey, and entertainment arena at the SoDo site. McGinn employed a stadium consultant on the city's behalf to study the viability of such a project. Local media took notice of the land purchases and began to postulate that it was for an arena. Rumors of meetings between McGinn and Hansen's investment group began to circulate in late 2011 and were finally acknowledged in early 2012.[citation needed]

At that time, rumors that Hansen would begin pursuing a vulnerable franchise to relocate to Seattle began making the rounds. Most of the discussion centered on the Sacramento Kings, a struggling franchise that had been trying to put together a plan to replace the aging Sleep Train Arena, then called the Power Balance Pavilion, for years with no luck. While Hansen had not spoken in public about his desires or pursuits for a specific team, the rumors were rampant enough that Think Big Sacramento, a community action group created by Sacramento mayor Kevin Johnson to develop solutions for the Kings, composed an open letter to Hansen asking him not to pursue the city's team.[39] Meanwhile, negotiations between McGinn, Constantine, and Hansen continued on development of a memorandum of understanding that would lay out the relationship for a public-private partnership on the new arena.[citation needed]

On May 16, 2012, after coming to agreement, McGinn, Constantine, and Hansen presented the proposed Memorandum of Understanding to the public.[40] McGinn and Constantine had insisted on a number of protections for the citizens of Seattle and King County, specifically that no public financing on the project would be committed until Hansen and his investors had secured an NBA team to be primary tenant. The MOU proposal included a financial model that made the project "self-financed", in which no new taxes would be levied to provide funds and city bonds issued would be paid back by taxes and revenue generated solely by the new arena. The proposal was turned over to the Seattle City Council and the King County Council for review and approval.[citation needed]

The King County Council voted to approve the MOU on July 30, 2012, adding amendments that provided for work with the Port of Seattle, securing the SuperSonics naming rights, offering reduced price tickets, support for the Seattle Storm WNBA franchise, and require an economic analysis.[41] The approval was also on the condition that any changes made by the Seattle City Council, which still had yet to vote on the proposal, would need to be voted on and approved separately. The Seattle council had announced that morning that amendments of their own were intended and negotiations began.[citation needed]

Hansen and the Seattle City Council announced on September 11, 2012, a tentative agreement on a revised MOU that included the county council's amendments and new provisions, specifically a personal guarantee from Hansen to cover not only cost overruns of construction of the new arena but to make up any backfall for annual repayment of the city bonds issued.[42] To address concerns of the Port of Seattle, the Seattle Mariners, and local industry, a SoDo transportation improvement fund to be maintained at $40 million by tax revenue generated by the arena was also included. Also, all parties agreed that transaction documents would not be signed and construction would not begin before the state required environmental impact analysis was completed. By a vote of 7–2, the Seattle City Council approved the amended MOU on September 24, 2012.[43] The King County Council reviewed the amended MOU and voted unanimously in favor of approval on October 15, 2012.[44] The final MOU was signed and fully executed by Mayor McGinn and Executive Constantine on October 18, 2012, starting an effective period of the agreement of five years.[citation needed]

In June 2012, it was revealed that Hansen's investment partners included then-Microsoft CEO Steve Ballmer and brothers Erik and Peter Nordstrom of fashion retailer Nordstrom, Inc.. Peter Nordstrom had been a minority owner of the SuperSonics under Howard Schultz's ownership. Wally Walker, former Sonics executive, was also later revealed to be part of Hansen's group. On January 9, 2013, media reports surfaced regarding the imminent sale of majority ownership of the Sacramento Kings to Hansen, Ballmer, the Nordstroms, and Walker for $500 million to relocate to Seattle as early as the 2013–14 NBA season.[45][46][47]

On January 20, 2013, several sources reported that the Maloof family had reached a binding purchase and sale agreement to sell Hansen and Ballmer's ownership group their 53% majority stake in the Kings franchise, pending approval of the NBA's Board of Governors.[48] The next day, the NBA, Hansen, and the Maloofs all released statements announcing the agreement, which also included the 12% minority stake of owner Robert Hernreich, and based the sale price on a team valuation of $525 million.[49][50][51] Sacramento mayor Johnson offered a quick rebuttal to the announcement, stating that the agreement was not a done deal and that Sacramento would have the opportunity to present a counteroffer to the NBA.[citation needed]

David Stern, then NBA Commissioner, confirmed on February 6, 2013, that the Maloofs had filed paperwork with the league office to officially request relocation of the Kings from Sacramento to Seattle on behalf of the potential new ownership group.[52] Johnson, with guidance from Stern and the NBA league office, began to assemble an alternative ownership group that would keep the Kings in Sacramento and aid in getting a new arena constructed. On February 26, 2013, the Sacramento City Council voted to enter into negotiations with an unnamed group of investors revealed two days later to be headed by grocery magnate and developer Ron Burkle and Mark Mastrov, founder of 24 Hour Fitness. An initial counteroffer presented to the NBA by this new group was deemed "not comparable" as to merit consideration.[53] Burkle eventually left the group because of a conflict with other business interests, but offered to be primary developer of lands around the planned downtown location of the new arena to aid in city council passage of public funding for the project.[54] Mastrov took a backseat to Vivek Ranadivé, founder and CEO of TIBCO and a minority owner of the Golden State Warriors, brought in to assemble a stronger group of investors.[55] Others, including Paul Jacobs, CEO of Qualcomm, Sacramento developer Mark Friedman, former Facebook executive Chris Kelly, and manufacturer Raj Bhathal, were added to the group to address team ownership and arena investment.[citation needed]

Ahead of the annual Board of Governors meeting where they were expected to vote on approval of the sale of the Kings to Hansen and Ballmer's group, as well as the relocation request, members of the NBA owners' finance and relocation committees held a meeting in New York City on April 3, 2013, for the Seattle group and the Sacramento group to each present their proposals.[56] Any vote would only be on the PSA presented by Hansen and Ballmer, and the Sacramento proposal was considered a "backup offer". Coming out of that meeting, the NBA removed the vote from the agenda of the BOG meeting and postponed it for two weeks while information was reviewed. Despite stated desires to the contrary, a bidding war began between Hansen's and Ranadivé's groups, including Hansen raising the team valuation of their offer twice from $525 million to $550 million to $625 million, and Ranadivé offering to forgo the team revenue sharing that has frequently kept smaller market teams like the Kings financially stable.[citation needed]

With the meeting of the Board of Governors to vote moved again to mid-May, the groups were asked to make another brief presentation to the full relocation committee on April 29, 2013. The committee voted to recommend rejection of the relocation request to the full board.[57] When the Board of Governors finally convened in Dallas on May 15, 2013, they heard final presentations from both the Seattle and Sacramento groups. The BOG voted 22–8 against moving the Kings from Sacramento to Seattle.[58] As the PSA for the sale of the team was, for all intents and purposes, dependent upon relocation, the NBA rejected the sale without vote.[citation needed]

Though initially resistant to the idea, after negotiations, on May 17, 2013, the Maloof family and Hernreich formally agreed to sell their ownership stake in the Kings (65% of the team, valued at US$535 million) to Ranadivé's ownership group.[59] Part of the $348 million purchase was considered paid with a $30 million non-refundable deposit Chris Hansen had paid to the Maloofs to establish their business relationship, though Hansen has no ownership stake in the team.[citation needed]

Milwaukee Bucks[]

In September 2013, then-Deputy Commissioner Adam Silver, in line to become the next commissioner upon David Stern's retirement in February 2014, made the announcement that the Milwaukee Bucks would need to replace the aging BMO Harris Bradley Center because of its small size and lack of amenities.[60] The team had recently signed a lease through the 2016–17 NBA season, but the NBA made it clear that the lease would not be renewed past that point. With counties surrounding Milwaukee passing ordinances that they would not approve a regional tax option to fund a new arena, rumors began swirling that owner Herb Kohl would need to sell all or part of his ownership of the team. Though Kohl had repeatedly stated he would not sell to someone intent on moving the Bucks out of Wisconsin, many[who?] had pegged the team as a likely potential candidate to move to Seattle.

On April 16, 2014, it was announced that Kohl had agreed to sell the franchise to New York hedge-fund investors Marc Lasry and Wesley Edens for a record $550 million. The deal included provisions for contributions of $100 million each from Kohl and the new ownership group, for a total of $200 million towards the construction of a new downtown arena.[61] During sale discussions, it was revealed that Hansen and Ballmer had expressed interest in purchasing the team for more than $600 million but had not made a formal offer because of Kohl's insistence that the team stay in Milwaukee.[62]

In the summer of 2015, the state of Wisconsin and city of Milwaukee agreed to help fund a new arena to replace the BMO Harris Bradley Center, and construction began in June 2016. The new arena, the Fiserv Forum, was completed in August 2018, with the Bucks also signing a 30-year lease with the city of Milwaukee.

Atlanta Hawks[]

On January 2, 2015, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution reported that Atlanta Spirit, then-owners of the Atlanta Hawks, would put the team up for sale. Initially, only majority owner Bruce Levenson would put his stake in the team up for sale; however, the remaining minority owners announced that they would sell their stakes as well, putting the entire franchise up for sale.[63] On January 6, 2015, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reported that Chris Hansen and film producer Thomas Tull (the latter a minority owner of the NFL's Pittsburgh Steelers) would put in separate bids to acquire the Hawks and move them to Seattle.[64] However, the NBA stated that the Hawks were to remain in Atlanta as a condition of their sale; additionally, Atlanta Spirit were unlikely to sell the Hawks to a prospective owner that would relocate the team, in contrast to how the group sold the now-defunct Atlanta Thrashers of the NHL in 2011.[63] Any attempt to move the Hawks out of Atlanta would have incurred a $75 million penalty from the city of Atlanta and Fulton County for breaking the Hawks' lease at Philips Arena before 2017.[65] The Hawks were sold to a group led by Tony Ressler on June 24, 2015.[66]

Future arena talks[]

On May 2, 2016, the Seattle City Council voted 5–4 against vacating a section of Occidental Avenue South, which connected property purchased by Hansen and was deemed critical to siting a future arena. The vote was seen as a significant setback to the memorandum of understanding between Hansen, the city and King County, which ran through November 2017.[67] On October 25, 2016, Chris Hansen announced he will fund the arena without public funding.[68] On November 14, 2016, Seattle Seahawks' quarterback Russell Wilson announced that he would be investing in the NBA arena effort.[69] However, the original deal would ultimately expire on December 3, 2017. Nevertheless, Hansen plans to keep the land owned in the Seattle Stadium District until a commitment for a new Seattle SuperSonics franchise occurs, especially in the event a potential back-up plan becomes warranted.

KeyArena renovations[]

While talks of building a new arena were underway, there were also talks from another group of investors on renovating the SuperSonics' former home, the KeyArena. One of the investors is Tim Leiweke, co-founder of the Oak View Group. On December 4, 2017, one day after the deal with SoDo investor Chris Hansen expired, the Seattle City Council voted 7–1 approving the renovation of the KeyArena, with one person not available for voting that day.[70][71] While the renovation is considered to have a main focus on fitting the Seattle Kraken for the National Hockey League (NHL), interest for the revival of the SuperSonics still remains a distinct possibility with the renovated arena. However, while Hansen and his fellow investors still feel having a future arena should be considered as a back-up plan for the future of the SuperSonics, they fully support the renovation and would be right beside the Oak View Group in cheering the team on moving forward if the plan on acquiring an NBA team becomes successful.[72] Renovations of KeyArena into Climate Pledge Arena began in 2018, a day after NHL approval of the new Seattle franchise with the renovations planned to be fully completed by the beginning of the 2021–22 NBA and NHL seasons.

Season-by-season records[]

Home arenas[]

- KeyArena (formerly Seattle Center Coliseum) 1967–1978, 1985–1994, 1995–2008

- The Kingdome 1978–1985

- Tacoma Dome 1994–1995 (during KeyArena remodel)

Uniforms[]

The Seattle SuperSonics' first uniforms had "Sonics" displayed in a font that was also used by the Cincinnati Royals (now the Sacramento Kings). The road jerseys were green and had the lettering displayed in yellow coloring, where the home uniforms were white and had the lettering green. In 1995, the SuperSonics changed their uniforms adding red and orange, removing yellow, to their new jerseys that would last six seasons. It displayed the new Sonics logo on the front and their alternate logo on the shorts. The home uniforms had green stripes on the right side of the jersey and shorts, while the green road jersey had red stripes.

The final SuperSonics uniforms were worn from the 2001-02 season through the 2007-08 season. They were commissioned by owner Howard Schultz for design by Seattle design agency Hornall Anderson. The home jerseys were white with green and gold trim, displaying "SONICS" across the chest. Road uniforms were dark green with white and gold accents, with "SEATTLE" across the chest. The alternate uniform was gold with green and white trim, again with "SONICS" arched across the chest. These uniforms were a nod to a similar style worn from the 1975–76 season through the 1994–95 season.[73]

Rivalries[]

The SuperSonics were traditional rivals with the Portland Trail Blazers because of the teams' proximity; the rivalry had been dubbed the I-5 Rivalry in reference to Interstate 5 that connects the two cities, which are only 174 miles apart. The rivalry was fairly equal in accomplishments, with both teams winning one championship each. The all-time record of this rivalry is 98–94 in favor of the SuperSonics.[74][75][76]

The SuperSonics were rivals of the Los Angeles Lakers, particularly due to the teams' longstanding pairing in the Pacific Division of the Western Conference. The Lakers' sustained success meant regular season games often impacted NBA Playoffs seedings, with the teams matching up head-to-head for numerous playoff battles.[77][78]

Achievements and honors[]

Retired numbers[]

| Seattle SuperSonics retired numbers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Player | Position | Tenure | Date |

| 1 | Gus Williams | G | 1977–1984 | March 26, 2004 |

| 10 | Nate McMillan | G | 1986–1998 1 | March 24, 1999 |

| 19 | Lenny Wilkens | G | 1968–1972 2 | October 19, 1979 |

| 24 | Spencer Haywood | F | 1971–1975 | February 26, 2007 |

| 32 | Fred Brown | G | 1971–1984 | November 6, 1986 |

| 43 | Jack Sikma | C | 1977–1986 | November 21, 1992 |

| Bob Blackburn | Broadcaster | 1967–1992 | April 17, 1993 | |

Notes:

- 1 Also head coach from 2000 to 2005.

- 2 Head coach during 1969–1972 and 1977–1985.

Basketball Hall of Famers[]

| Seattle SuperSonics Hall of Famers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Players | ||||

| No. | Name | Position | Tenure | Inducted |

| 19 | Lenny Wilkens 1 | G | 1968–1972 | 1989 |

| 44 | David Thompson | F/G | 1982–1984 | 1996 |

| 33 | Patrick Ewing 2 | C | 2000–2001 | 2008 |

| 24 | Dennis Johnson 3 | G | 1976–1980 | 2010 |

| 2 20 |

Gary Payton | G | 1990–2003 | 2013 |

| 30 | Šarūnas Marčiulionis | G | 1994–1995 | 2014 |

| 24 | Spencer Haywood | F/C | 1970–1975 | 2015 |

| 34 | Ray Allen | G | 2003–2007 | 2018 |

| 43 | Jack Sikma 4 | C | 1977–1986 | 2019 |

| 44 | Paul Westphal 5 | G | 1980–1981 | 2019 |

| Coaches | ||||

| Name | Position | Tenure | Inducted | |

| Lenny Wilkens 1 | Head coach | 1969–1972 1977–1985 |

1998 | |

| Bill Russell 6 | Head coach | 1973–1977 | 2021 | |

| Contributors | ||||

| Name | Position | Tenure | Inducted | |

| 44 | Rod Thorn | G | 1967–1971 | 2018 |

Notes:

- 1 In total, Wilkens was inducted into the Hall of Fame three times – as player, as coach and as a member of the 1992 Olympic team.

- 2 In total, Ewing was inducted into the Hall of Fame twice – as player and as a member of the 1992 Olympic team.

- 3 Inducted posthumously.

- 4 Also served as assistant coach (2003–2007).

- 5 Also served as head coach (1998–2000).

- 6 In total, Russell was inducted into the Hall of Fame twice – as a player and as coach.

FIBA Hall of Famers[]

| Seattle SuperSonics Hall of Famers | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Players | ||||

| No. | Name | Position | Tenure | Inducted |

| 30 | Šarūnas Marčiulionis | G | 1994–1995 | 2015 |

| 11 | Detlef Schrempf | F | 1993–1999 | 2021 |

State of Washington Sports Hall of Fame[]

Individual awards[]

NBA Defensive Player of the Year

- Gary Payton – 1996

- Kevin Durant – 2008

NBA Finals MVP

- Dennis Johnson – 1979

- Zollie Volchok – 1983

- Bob Whitsitt – 1994

NBA Most Improved Player Award

- Dale Ellis – 1987

J. Walter Kennedy Citizenship Award

- Slick Watts – 1976

- Hersey Hawkins – 1999

- Ray Allen – 2003

All-NBA First Team

- Spencer Haywood – 1972, 1973

- Gus Williams – 1982

- Gary Payton – 1998, 2000

All-NBA Second Team

- Spencer Haywood – 1974, 1975

- Dennis Johnson – 1980

- Gus Williams – 1980

- Shawn Kemp – 1994, 1995, 1996

- Gary Payton – 1995, 1996, 1997, 1999, 2002

- Vin Baker – 1998

- Ray Allen – 2005

All-NBA Third Team

- Dale Ellis – 1989

- Gary Payton – 1994, 2001

- Detlef Schrempf – 1995

NBA All-Defensive First Team

- Slick Watts – 1976

- Dennis Johnson – 1979, 1980

- Gary Payton – 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002

NBA All-Defensive Second Team

- Lonnie Shelton – 1982

- Jack Sikma – 1982

- Danny Vranes – 1985

- Nate McMillan – 1994, 1995

NBA All-Rookie First Team

- Bob Rule – 1968

- Al Tucker – 1968

- Art Harris – 1969

- Tom Burleson – 1975

- Jack Sikma – 1978

- Xavier McDaniel – 1986

- Derrick McKey – 1988

- Jeff Green – 2008

- Kevin Durant – 2008

NBA All-Rookie Second Team

- Gary Payton – 1991

- Desmond Mason – 2001

- Vladimir Radmanović – 2002

- All-Star Game

- Walt Hazzard – 1968

- Lenny Wilkens – 1969, 1970, 1971

- Bob Rule – 1969

- Spencer Haywood – 1972, 1973, 1974 ,1975

- Fred Brown – 1976

- Dennis Johnson – 1979, 1980

- Jack Sikma – 1979, 1980, 1981, 1982, 1983, 1984, 1985

- Paul Westphal – 1981

- Lonnie Shelton – 1982

- Gus Williams – 1982, 1983

- David Thompson – 1983

- Tom Chambers – 1987

- Xavier McDaniel – 1988

- Dale Ellis – 1989

- Shawn Kemp – 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997

- Gary Payton – 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003

- Detlef Schrempf – 1995, 1997

- Vin Baker – 1998

- Ray Allen – 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007

- Rashard Lewis – 2005

NBA All-Star Game MVPs

- Lenny Wilkens – 1971

- Tom Chambers – 1987

Staff[]

- Head coaches

| Coaching history | ||||

| Coach | Tenure | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Al Bianchi | 1967–1969 | |||

| Lenny Wilkens | 1969–1972 | |||

| Tom Nissalke | 1972–1973 | |||

| Bucky Buckwalter | 1972–1973 | |||

| Bill Russell | 1973–1977 | |||

| Bob Hopkins | 1977 | |||

| Lenny Wilkens | 1977–1985 | |||

| Bernie Bickerstaff | 1985–1990 | |||

| K. C. Jones | 1990–1992 | |||

| Bob Kloppenburg | 1992 | |||

| George Karl | 1992–1998 | |||

| Paul Westphal | 1998–2000 | |||

| Nate McMillan | 2000–2005 | |||

| Bob Weiss | 2005 | |||

| Bob Hill | 2006–2007 | |||

| P. J. Carlesimo | 2007–2008 | |||

- General managers

| GM history | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM | Tenure | |||

| Don Richman | 1967–1968 | |||

| Dick Vertlieb | 1968–1970 | |||

| Bob Houbregs | 1970–1973 | |||

| Bill Russell | 1973–1977 | |||

| Zollie Volchok | 1977 (or 1978)[citation needed]–1983 | |||

| Les Habegger | 1983–1985 | |||

| Lenny Wilkens | 1985–1986 | |||

| Bob Whitsitt | 1986–1994 | |||

| Wally Walker | 1994–2001 | |||

| Rick Sund | 2001–2007 | |||

| Sam Presti | 2007–2008 | |||

Records and leaders[]

Franchise leaders[]

Points scored (regular season) (as of the end of the 2007–08 season)[79]

- Gary Payton (18,207)

- Fred Brown (14,018)

- Jack Sikma (12,258)

- Rashard Lewis (12,034)

- Shawn Kemp (10,148)

- Gus Williams (9,676)

- Dale Ellis (9,405)

- Xavier McDaniel (8,438)

- Spencer Haywood (8,131)

- Tom Chambers (8,028)

- Ray Allen (7,237)

- Detlef Schrempf (6,870)

- Dick Snyder (6,507)

- Derrick McKey (6,159)

- Lenny Wilkens (6,010)

- Bob Rule (5,646)

- Vin Baker (5,054)

- Sam Perkins (4,844)

- Nate McMillan (4,733)

- Dennis Johnson (4,590)

- Lonnie Shelton (4,460)

- Ricky Pierce (4,393)

- Brent Barry (4,107)

- Tom Meschery (4,050)

- Hersey Hawkins (3,798)

- Michael Cage (3,742)

- Eddie Johnson (3,714)

- John Johnson (3,608)

- Slick Watts (3,396)

- Al Wood (3,265)

Other Statistics (regular season) (as of the end of the 2007–08 season)[79]

| Most minutes played | |

|---|---|

| Player | Minutes |

| Gary Payton | 36,858 |

| Jack Sikma | 24,707 |

| Fred Brown | 24,422 |

| Rashard Lewis | 20,921 |

| Nate McMillan | 20,462 |

| Most rebounds | |

|---|---|

| Player | Rebounds |

| Jack Sikma | 7,729 |

| Shawn Kemp | 5,978 |

| Gary Payton | 4,240 |

| Michael Cage | 3,975 |

| Spencer Haywood | 3,954 |

| Most assists | |

|---|---|

| Player | Assists |

| Gary Payton | 7,384 |

| Nate McMillan | 4,893 |

| Fred Brown | 3,160 |

| Gus Williams | 2,865 |

| Lenny Wilkens | 2,777 |

| Most steals | |

|---|---|

| Player | Steals |

| Gary Payton | 2,107 |

| Nate McMillan | 1,544 |

| Fred Brown | 1,149 |

| Gus Williams | 1,086 |

| Slick Watts | 833 |

| Most blocks | |

|---|---|

| Player | Blocks |

| Shawn Kemp | 959 |

| Jack Sikma | 705 |

| Alton Lister | 500 |

| Tom Burleson | 420 |

| Derrick McKey | 375 |

Single-season and career leaders[]

Individual leaders[]

|

|

See also[]

- Bob Blackburn, late primary play-by-play broadcaster, "The Voice of the Seattle SuperSonics" – 1967–1992

- Kevin Calabro, primary play-by-play broadcaster, 1987–2008

- The Wheedle, team mascot, 1978–1985

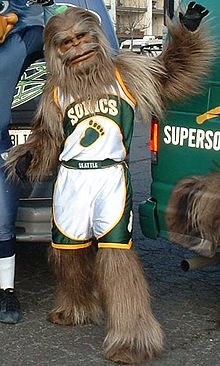

- Squatch, team mascot, 1993–2008

- Save Our Sonics, grassroots organization dedicated to preventing the team's move from Seattle in 2008.

- Sonicsgate, a 2009 feature documentary chronicling the SuperSonics' history, sale and relocation

- Sonics Arena, a proposal led by American hedge fund manager Chris R. Hansen to build a new multi-purpose arena in the neighborhood south of downtown Seattle

- List of relocated National Basketball Association teams

References[]

- ^ "History: Team by Team–Oklahoma City Thunder" (PDF). 2019-20 Official NBA Guide. NBA Properties, Inc. October 17, 2019. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "NBA.com/Stats–Oklahoma City Thunder seasons". Stats.NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Retrieved June 28, 2020.

- ^ "Sonics Unveil New Logo and Official Colors". SuperSonics.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. August 25, 2001. Archived from the original on December 18, 2001. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Basketball Club of Seattle Announces Sale of Sonics & Storm". SuperSonics.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. July 18, 2006. Archived from the original on July 19, 2006. Retrieved July 19, 2006.

- ^ "NBA Board of Governors Approves Sale of Sonics & Storm". SuperSonics.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. October 24, 2006. Archived from the original on November 8, 2006. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- ^ Allen, Percy (October 24, 2006). "NBA board approves sale of Sonics, Storm". The Seattle Times. Retrieved October 24, 2006.

- ^ Brunner, Jim; Chan, Sharon Pian (July 2, 2008). "Sonics, city reach settlement". The Seattle Times. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Aldridge, David (December 13, 2010). "Two years later, pain of losing Sonics still stings Seattle". NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "The Professional Basketball Club, LLC and City of Seattle Settlement Agreement" (PDF). www.seattle.gov. August 18, 2008. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- ^ "Details of settlement between Bennett, Seattle revealed". ESPN.com. August 20, 2008. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ "Behind The Name – Sonics". OKCThunder.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "Seattle SuperSonics, Part 1". historylink.org.

Seattle's National Basketball Association team for 41 years, the SuperSonics were the city's first major league sports franchise and won a championship in 1979.

- ^ Andrieson, David (October 12, 2007). "Sonics ushered Seattle into the big time 40 years ago Saturday". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ Pluto, Terry, Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association (Simon & Schuster, 1990), ISBN 978-1-4165-4061-8, p.200

- ^ Pluto, Terry, Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association (Simon & Schuster, 1990), ISBN 978-1-4165-4061-8, p.186

- ^ History in Headlines of the Sonics. Celebrity Services. 1979. p. 11.

- ^ Raley, Dan (November 1, 2005), "Where Are They Now? Butch Beard: Sonic turned coach", Seattle Post-Intelligencer

- ^ Richardson, Kenneth (January 27, 1989). "Sonics Going Dome Tonight: Hawks in Rare Kingdome Visit". The Seattle Post-Intelligencer.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "RICK WELTS BIO". Suns.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Peoples, John (November 19, 1993). "TV / Radio Notebook -- Sonics, Four Others Tap Pay-Per-View". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- ^ "PRO BASKETBALL; Westphal Is Fired by Sonics After Feuding With Players". The New York Times. November 28, 2000. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Frank (November 27, 2000). "Westphal firing was inevitable, but wrong". ESPN.com. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ "McMillan, Sonics Come To Terms". CBS News. February 28, 2001. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ "Seattle Supersonics (1967–2008)". Sportsecyclopedia.com. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ "Five years after 'gut wrenching' fight, Kings are going to Seattle – for one night only". The Sacramento Bee. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- ^ "Sonics, Storm sold to group from Oklahoma City – NBA – ESPN". ESPN.com. July 19, 2006. Retrieved July 20, 2012.

- ^ Johns, Greg (November 2, 2007). "Bennett says Sonics going to Oklahoma". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved November 15, 2007.

- ^ "Judge blocks Sonics from taking arena dispute to arbitration". ESPN. Associated Press. October 29, 2007. Retrieved October 30, 2007.

- ^ "City of Seattle v. Professional Basketball Club LLC", Justia.com October 9, 2007.

- ^ "NBA Board of Governors Approve Sonics Move to Oklahoma City Pending Resolution of Litigation". NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. April 18, 2008. Retrieved April 19, 2008.

- ^ "NBA Commissioner David Stern Statement on Settlement Between Sonics and the City of Seattle". NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. July 2, 2008. Retrieved July 2, 2008.

- ^ Johns, Greg; Galloway, Angela (July 2, 2008). "Sonics are Oklahoma City-bound". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved July 3, 2008.

- ^ Brunner, Jim (April 17, 2008). "E-mails reveal Sonics owners intended to bolt from Seattle". The Seattle Times. Retrieved April 18, 2008.

- ^ Allen, Percy (April 15, 2008). "Howard Schultz plans to sue Clay Bennett to get Sonics back". The Seattle Times. Retrieved April 16, 2008.

- ^ Brunner, Jim; Allen, Percy (August 29, 2008). "Schultz withdraws lawsuit on sale of Sonics". The Seattle Times. Retrieved August 30, 2008.

- ^ "Sonicsgate". Webby Awards. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- ^ Miletich, Steve; Thompson, Lynn (February 4, 2012). "Seattle sports-arena talks well under way, documents show". The Seattle Times. Retrieved February 5, 2012.

- ^ "McGinn offered KeyArena to Chris Hansen for free". KOMONews.com. April 16, 2012. Retrieved December 6, 2020.

- ^ Napear, Grant (February 13, 2012). "Think Big Sacramento's Open Letter To Chris Hansen". CBS Sacramento.

- ^ "County Executive, Mayor and Chris Hansen reach agreements for arena". Office of Mayor Mike McGinn, City of Seattle (mayormcginn.seattle.gov). May 16, 2012.

- ^ Young, Bob (July 30, 2012). "The Today File: King County Council approves arena proposal". Seattle Times.

- ^ Thompson, Lynn (September 11, 2012). "City Council reaches revised arena deal". The Seattle Times. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- ^ Thompson, Lynn (September 24, 2012). "The Today File: Seattle City Council approves new arena". Seattle Times.

- ^ "Seattle arena deal gets final approval". ESPN. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ "Report: Maloofs finalizing deal to sell Kings to Seattle group". CBSSports.com. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Adrian Wojnarowski (January 9, 2013). "Maloofs nearing deal to sell Kings to group that plans to relocate franchise to Seattle". Yahoo! Sports. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Howard-Cooper, Scott (January 9, 2013). "Sacramento Kings Being Sold To Seattle-Based Group". NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Amick, Sam (January 20, 2013). "Sacramento Kings reach agreement with Seattle group". USA Today. Retrieved January 21, 2013.

- ^ Golliver, Ben (January 21, 2013). "NBA announces Maloofs' deal to sell Kings to Seattle". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Hansen, Chris (January 21, 2013). "An Announcement". SonicsArena.com. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ Goyette, Jared (January 21, 2013). "Maloof family (finally) announces agreement to seel Kings". Sacramento Press. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ "Seattle group has filed for relocation". ESPN (AP). February 7, 2013.

- ^ Helin, Kurt (March 8, 2013). "David Stern says Sacramento group needs to up offer for Kings". NBC Sports Pro Basketball Talk.

- ^ Amick, Sam (April 8, 2013). "Ron Burkle no longer in Sacramento group to buy Kings". USA Today.

- ^ Bizjak, Tony (March 21, 2013). "City Beat: Third big investor emerges in bid for Sacramento Kings". Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on April 11, 2013.

- ^ Mahoney, Brian (April 3, 2013). "Sacramento, Seattle Groups Present to NBA Owners". Associated Press.

- ^ "Committee recommends Kings stay put". NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Associated Press. April 29, 2013. Retrieved April 30, 2013.

- ^ "Kings to stay in Sacramento as owners reject Seattle move". NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Associated Press. May 15, 2013. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Aldridge, David (May 17, 2013). "Maloof family agrees to sell Kings for record $535 million". NBA.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. Retrieved May 7, 2015.

- ^ Kirchen, Rich (September 18, 2013). "Incoming NBA commissioner Silver says Bradley Center unfit for league". Milwaukee Business Journal. Retrieved September 19, 2013.

- ^ Walker, Don (April 17, 2014). "Kohl sells Bucks for $550 million; $200 million pledged for new arena". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- ^ Simmons, Bill (April 17, 2014). "The World's Most Exclusive Club". Grantland.com.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vivlamore, Chris (January 2, 2015). "Breaking News: 100 percent of Hawks up for sale (updated)". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ Eaton, Nick (January 6, 2015). "Chris Hansen, Thomas Tull planning bids to bring NBA's Atlanta Hawks to Seattle". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved January 7, 2015.

- ^ Eaton, Nick (January 8, 2015). "NBA: Atlanta Hawks will not move to Seattle, or anywhere". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved January 9, 2015.

- ^ "Group Led By Tony Ressler Completes Purchase of Atlanta Hawks". Hawks.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. June 25, 2015. Retrieved January 29, 2019.

- ^ Baker, Geoff (May 2, 2016). "Seattle City Council kills sale of street for Sodo arena". The Seattle Times. Retrieved May 3, 2016.

- ^ Coppinger, Mike (October 25, 2016). "Chris Hansen says he has private money for Seattle arena". USA Today. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Bell, Gregg (November 14, 2016). "Russell Wilson's latest popular Seattle play: Co-investing in Chris Hansen's NBA arena effort". The News Tribune. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Baker, Geoff (December 4, 2017). "KeyArena MOU approved by Seattle City Council; will NHL announcement soon follow?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ Daniels, Chris (December 4, 2017). "KeyArena renovation wins approval from Seattle City Council". KING5.com. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ "Sonics Arena Team on the Seattle City Council's approval of the Oak View Group MOU". Sonics Arena. December 4, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- ^ "New Uniforms Go Back to the Future". SuperSonics.com. NBA Media Ventures, LLC. October 1, 2001. Archived from the original on December 2, 2001. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ Tokito, Mike (February 16, 2012). "Trail Blazers owner Paul Allen issues statement on possibility of Seattle getting NBA team". The Oregonian. Retrieved February 17, 2012.

- ^ "RealClearSports – Top 10 Defunct Rivalries – 9. Sonics-Blazers". Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Smith, Rob (January 21, 2013). "It's back on in the NBA! Portland vs. Seattle". Portland Business Journal. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Kelley, Steve (April 17, 2010). "It should be the Sonics playing the Lakers in the first round of the playoffs". The Seattle Times. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- ^ Jonathan Irwin. "Seattle Supersonics". Bleacher Report. Retrieved June 30, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Nuggets Career Leaders : Statistics". Basketball Reference. June 27, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2011.

- ^ Bob Rule averaged 29.8 points per game for the SuperSonics in the 1970–71 season, but only played in four games, thereby missing the standard qualification minimums

External links[]

![]() Media related to Seattle SuperSonics at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Seattle SuperSonics at Wikimedia Commons

- Official Site (February 2008) (Archived)

- Seattle SuperSonics

- Basketball teams established in 1967

- Basketball teams disestablished in 2008

- Oklahoma City Thunder

- Relocated National Basketball Association teams

- Basketball teams in Seattle

- 1967 establishments in Washington (state)

- 2008 disestablishments in Washington (state)

- Defunct brands