Self-referential humor

Self-referential humor, also known as self-reflexive humor or meta humor, is a type of comedic expression[1] that—either directed toward some other subject, or openly directed toward itself—is self-referential in some way, intentionally alluding to the very person who is expressing the humor in a comedic fashion, or to some specific aspect of that same comedic expression. Self-referential humor expressed discreetly and surrealistically is a form of bathos. In general, self-referential humor often uses hypocrisy, oxymoron, or paradox to create a contradictory or otherwise absurd situation that is humorous to the audience.

History[]

Old Comedy of Classical Athens is held to be the first—in the extant sources—form of self-referential comedy. Aristophanes, whose plays form the only remaining fragments of Old Comedy, used fantastical plots, grotesque and inhuman masks and status reversals of characters to slander prominent politicians and court his audience's approval.[2]

Self-referential humor was popularized by Douglas Hofstadter who wrote several books on the subject of self-reference,[3][4] the term meta has come to be used, particularly in art, to refer to something that is self-referential.[5]

Classification[]

Meta-jokes are a popular form of humor. They contain several somewhat different, but related categories: joke templates, self-referential jokes, and jokes about jokes (meta-humour).[citation needed]

Joke template[]

This form of meta-joke is a sarcastic jab at the endless refitting of joke forms (often by professional comedians) to different circumstances or characters without a significant innovation in the humor.[6]

Three people of different nationalities walk into a bar. Two of them say something smart, and the third one makes a mockery of his fellow countrymen by acting stupid.[7]

Three blokes walk into a pub. One of them is a little bit stupid, and the whole scene unfolds with a tedious inevitability.[8] —Bill Bailey

How many members of a certain demographic group does it take to perform a specified task?

A finite number: one to perform the task and the remainder to act in a manner stereotypical of the group in question.[7]

Self-referential jokes[]

Truly self-referential jokes are quite rare, as they must refer to themselves rather than to larger classes of previous jokes.

What do you get when you cross a joke with a rhetorical question?[9]

Three blind mice walk into a bar, but they are unaware of their surroundings so to derive humour from it would be exploitative.[8]

When I said I was going to become a comedian, they all laughed. Well, they're not laughing now, are they?[10]

Jokes about jokes ("meta-humor")[]

Meta-humour is humour about humour. Here meta is used to describe that the joke explicitly talks about other jokes, a usage similar to the words metadata (data about data), metatheatrics (a play within a play, as in Hamlet), and metafiction.

Other examples[]

Alternate punchlines[]

Another kind of meta-humour makes fun of poor jokes by replacing a familiar punchline with a serious or nonsensical alternative. Such jokes expose the fundamental criterion for joke definition, "funniness", via its deletion. Comedians such as George Carlin and Mitch Hedberg used metahumour of this sort extensively in their routines.

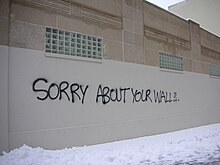

Anti-humor[]

Anti-humor is a type of indirect and alternative comedy that involves the joke-teller delivering something that is intentionally not funny, or lacking in intrinsic meaning. The humor of such jokes is based on the surprise factor of absence of an expected joke or of a punch line in a narration that is set up as a joke.[11][12] It depends upon reference to the audience's expectations on what a joke is.

Breaking the fourth wall[]

Self-referential humor is sometimes combined with breaking the fourth wall to explicitly make the reference directly to the audience, or make self-reference[13] to an element of the medium that the characters should not be aware of.

Class-referential jokes[]

This form of meta-joke contains a familiar class of jokes as part of the joke.

Bar jokes[]

A guy walks into a bar and says "ouch!"[14]

A baby seal walks into a club.[15]

A dangling participle walks into a bar. Enjoying a cocktail and chatting with the bartender, the evening passes pleasantly.[16]

A misplaced modifier walks into a bar owned by a man with a glass eye named Ralph.[16]

A bar was walked into by the passive voice.[16]

A verb walks into a bar, sees a beautiful noun, and suggests they conjugate. The noun declines.[16]

A non sequitur walks into a bar. In a strong wind, even turkeys can fly.[16]

Three logicians walk into a bar. The bartender asks "Do all of you want a drink?" The first logician says "I don’t know." The second logician says "I don’t know." The third logician says "Yes!"[9]

Comedian jokes[]

The process of being a humorist is also the subject of meta-jokes; for example, on an episode of QI, Jimmy Carr made the comment, "When I told them I wanted to be a comedian, they laughed. Well, they're not laughing now!"— a joke previously associated with Bob Monkhouse.[17]

Limericks[]

A limerick referring to the anti-humor of limericks:

The limerick packs laughs anatomical

Into space that is quite economical.

But the good ones I've seen

So seldom are clean

And the clean ones so seldom are comical.[18]

W. S. Gilbert wrote one of the definitive "anti-limericks":

Tom Stoppard's anti-limerick from Travesties:

A performative poet of Hibernia

Rhymed himself into a hernia

He became quite adept

At this practice, except

For the occasional non-sequitur.

Metaparody[]

Metaparody is a form of humor or literary technique consisting "parodying the parody of the original", sometimes to the degree that the viewer is unclear as to which subtext is genuine and which subtext parodic.[21][22][23]

RAS Syndrome[]

RAS syndrome refers to the redundant use of one or more of the words that make up an acronym or initialism with the abbreviation itself, thus in effect repeating one or more words. However, "RAS" stands for Redundant Acronym Syndrome; therefore, the full phrase yields "Redundant Acronym Syndrome syndrome" and is self-referencing in a comical manner. It also reflects an excessive use of TLAs (Three Letter Acronyms).[24][25][26]

Exemplars[]

Hedberg[]

Stand-up comedian Mitch Hedberg would often follow up a joke with an admission that it was poorly told, or insist to the audience that "that joke was funnier than you acted."[27]

Rehnquist[]

Marc Galanter in the introduction to his book Lowering the Bar: Lawyer Jokes and Legal Culture cites a meta-joke in a speech of Chief Justice William Rehnquist:

I've often started off with a lawyer joke, a complete caricature of a lawyer who's been nasty, greedy, and unethical. But I've stopped that practice. I gradually realized that the lawyers in the audience didn't think the jokes were funny and the non-lawyers didn't know they were jokes.[28]

White[]

E. B. White has joked about humour, saying that "[h]umour can be dissected, as a frog can, but the thing dies in the process and the innards are discouraging to any but the pure scientific mind."[29]

See also[]

- Indirect self-reference

- In-joke

- Intertextuality

- Irony

- Meta – Prefix meaning more comprehensive or transcending

- Meta-reference – Type of self reference

- Self-reference – Sentence, idea or formula that refers to itself

- Snowclone – Neologism for a type of cliché and phrasal template

References[]

- ^ "Sentences about Self-Reference and Recurrence". .vo.lu. Retrieved 2012-08-21.

- ^ Alan Hughes; Performing Greek Comedy (Cambridge, 2012)

- ^ Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1979), Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-026850

- ^ Hofstadter, Douglas R. (1985), Metamagical Themas: Questing for the Essence of Mind and Pattern, Basic Books, ISBN 0-465-04566-9

- ^ "Origin and meaning of prefix meta-". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved August 12, 2021.

- ^ "Stars turn to jokers for hire"[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Foster, Michael Dylan; Tolbert, Jeffrey A. (November 2015). The Folkloresque: Reframing Folklore in a Popular Culture World. Utah State University Press. ISBN 9781607324188.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bill Bailey (2004). Bill Bailey Live - Part Troll (DVD). Universal Pictures UK. ASIN B0002SDY1M.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "30 Jokes Only Intellectuals Will Understand". Fact-inator. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ "Obituary: Bob Monkhouse". BBC News. 29 December 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- ^ Warren A. Shibles, Humor Reference Guide: A Comprehensive Classification and Analysis Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine (Hardcover) 1998 ISBN 0-8093-2097-5

- ^ John Henderson, "Writing Down Rome: Satire, Comedy, and Other Offences in Latin Poetry" (1999) ISBN 0-19-815077-6, p. 218

- ^ "Self-referential humor," in Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia; (Wikimedia Foundation Inc., updated 15:05, Sunday, September 19, 2021 (UTC))

- ^ Rich, Jr., John D. (21 Mar 2019). "A Guy Walks Into a Bar and Says "Ouch!"". Psychology Today. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Inman, Matthew (2020). "A baby seal walks into a club...... Dumb Jokes That Are Funny - The Oatmeal". The Oatmeal. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Sienkiewicz, Linda K. (14 May 2018). "Bar Jokes and Grammar - Linda K Sienkiewicz". Linda K Sienkiewicz. Retrieved 21 February 2021.

- ^ Deacon, Michael (3 June 2015). "Modern comedy's unlikely hero: Bob Monkhouse". telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 18 February 2018.

- ^ Feinberg, Leonard. The Secret of Humor. Rodopi, 1978. ISBN 9789062033706. p102

- ^ Wells 1903, pp. xix-xxxiii.

- ^ Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia Of Literature - Google Boeken

- ^ Morson, Gary Saul; Emerson, Caryl (1989). Rethinking Bakhtin: extensions and challenges. Northwestern University Press. pp. 63–. ISBN 978-0-8101-0810-3. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Marina Terkourafi (23 September 2010). The Languages of Global Hip Hop. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 234–. ISBN 978-0-8264-3160-8. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Peter I. Barta (2001). Carnivalizing Difference: Bakhtin and the Other. Routledge. pp. 110–. ISBN 978-0-415-26991-9. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ^ Clothier, Gary (8 November 2006). "Ask Mr. Know-It-All". The York Dispatch.

- ^ Newman, Stanley (December 20, 2008). "Sushi by any other name". Windsor Star. p. G4. Archived from the original on May 3, 2012.

- ^ "Feedback" (fee required). New Scientist (2285). 2001-04-07. p. 108. Retrieved 2006-12-08.

- ^ "Mitch Hedberg - Mitch All Together", CD Comedy Central (2003) ASIN B000X71NKQ

- ^ Galanter, Marc (1 September 2005). Lowering the Bar: Lawyer Jokes and Legal Culture. University of Wisconsin Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-299-21350-1.

- ^ "Some Remarks on Humor", preface to A Subtreasury of American Humor (1941)

- Humour

- Self-reference

- Jokes