Self-sovereign identity

This article provides insufficient context for those unfamiliar with the subject. (June 2020) |

Self-sovereign identity (SSI) is an approach to digital identity that gives individuals control of their digital identities.[2]

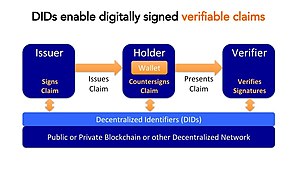

SSI addresses the difficulty of establishing trust in an interaction. In order to be trusted, one party in an interaction will present credentials to the other parties, and those relying parties can verify that the credentials came from an issuer that they trust. In this way, the verifier's trust in the issuer is transferred to the credential holder.[3] This basic structure of SSI with three participants is sometimes called "the trust triangle".[4]

It is generally recognized that for an identity system to be self-sovereign, users control the verifiable credentials that they hold and their consent is required to use those credentials.[5] This reduces the unintended sharing of users' personal data. This is contrasted with the centralized identity paradigm where identity is provided by some outside entity.[6]

In an SSI system, holders generate and control unique identifiers called decentralized identifiers. Most SSI systems are decentralized, where the credentials are managed using crypto wallets and verified using public-key cryptography anchored on a distributed ledger.[7] The credentials may contain data from an issuer's database, a social media account, a history of transactions on an e-commerce site, or attestation from friends or colleagues.

European Union SSI[]

The European Union is creating an eIDAS compatible European Self-Sovereign Identity Framework (ESSIF). The ESSIF makes use of decentralized identifiers (DIDs) and the European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI).[8][9]

References[]

- ^ "Decentralized Identifiers (DIDs)". World Wide Web Consortium. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ^ Ferdous, Md Sadek; Chowdhury, Farida; Alassafi, Madini O. (2019). "In Search of Self-Sovereign Identity Leveraging Blockchain Technology". IEEE Access. 7: 103059–103079. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2931173. ISSN 2169-3536.

- ^ Mühle, Alexander; Grüner, Andreas; Gayvoronskaya, Tatiana; Meinel, Christoph (2018). "A survey on essential components of a self-sovereign identity". Computer Science Review. 30 (1): 80–86. arXiv:1807.06346. doi:10.1016/j.cosrev.2018.10.002.

- ^ Reed, Drummond; Preukschat, Alex (2021). Self-Sovereign Identity. Manning. p. Chapter 2. ISBN 9781617296598.

- ^ Allen, Christopher (April 25, 2016). "The Path to Self-Sovereign Identity". Life With Alacrity. Retrieved February 19, 2021.

Users must control their identities.… Users must agree to the use of their identity.

- ^ "eIDAS supported self-sovereign identity" (PDF). European Commission. May 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Blockchain and digital identity" (PDF). eublockchainforum.eu. 2 May 2019. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- ^ "Understanding the European Self-Sovereign Identity Framework (ESSIF)". ssimeetup.org. 7 July 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ^ "European Blockchain Services Infrastructure (EBSI)". European Commission. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

See also[]

- Authentication methods

- Computer access control

- Digital technology

- Federated identity

- Identity management

- Sovereignty