Shofar

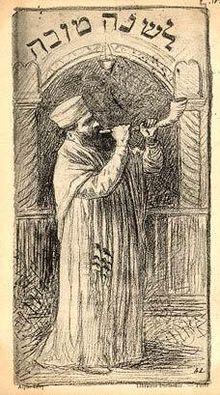

A shofar (pron. /ʃoʊˈfɑːr/, from Hebrew: ![]() שׁוֹפָר (help·info), pronounced [ʃoˈfaʁ]) is an ancient musical horn typically made of a ram's horn, used for Jewish religious purposes. Like the modern bugle, the shofar lacks pitch-altering devices, with all pitch control done by varying the player's embouchure. The shofar is blown in synagogue services on Rosh Hashanah and at the end of Yom Kippur; it is also blown every weekday morning in the month of Elul running up to Rosh Hashanah.[1] Shofars come in a variety of sizes and shapes, depending on the choice of animal and level of finish.

שׁוֹפָר (help·info), pronounced [ʃoˈfaʁ]) is an ancient musical horn typically made of a ram's horn, used for Jewish religious purposes. Like the modern bugle, the shofar lacks pitch-altering devices, with all pitch control done by varying the player's embouchure. The shofar is blown in synagogue services on Rosh Hashanah and at the end of Yom Kippur; it is also blown every weekday morning in the month of Elul running up to Rosh Hashanah.[1] Shofars come in a variety of sizes and shapes, depending on the choice of animal and level of finish.

Bible and rabbinic literature[]

The shofar is mentioned frequently in the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud and rabbinic literature. In the first instance, in Exodus 19, the blast of a shofar emanating from the thick cloud on Mount Sinai makes the Israelites tremble in awe.

The shofar was used to announce the new moon[2] and the Jubilee year.[3] The first day of Tishrei (now known as Rosh Hashana) is termed a "memorial of blowing",[4] or "day of blowing",[5] the shofar. Shofars were used for signifying the start of a war.[6] They were also employed in processions[7] as musical accompaniment,[8] and were inserted into the temple orchestra by David.[9] Note that the "trumpets" described in Numbers 10 are a different instrument, described by the Hebrew word for 'trumpet' (Hebrew: חצוצרה, romanized: ḥaṣoṣrah), not shofar (Hebrew: שופר).[10]

In the Temple in Jerusalem, the shofar was sometimes used together with the trumpet. On Rosh Hashana the principal ceremony was conducted with the shofar, which instrument was placed in the center with a trumpet on either side; it was the horn of a wild goat and straight in shape, being ornamented with gold at the mouthpiece. On fast days the principal ceremony was conducted with the trumpets in the center and with a shofar on either side. On those occasions the shofarot were rams' horns curved in shape and ornamented with silver at the mouthpieces.[11]

On Yom Kippur of the jubilee year the ceremony was performed with the shofar as on New Year's Day.[12] Shofar first indicated in Yovel (Jubilee Year—Lev. 25:8–13). Indeed, in Rosh Hashanah 33b, the sages ask why the Shofar sounded in Jubilee year. Rosh Hashanah 29a indicates that in ordinary years both Shofars and trumpets are sounded but in the Jubilee Year only the Shofar blasts. The Rabbi's created the practice of the Shofar's sounding every Yom Kippur rather than just on the Jubilee Year (once in 50 years).

Otherwise, for all other special days, the Shofar is sounded shorter and two special silver Trumpets announced the sacrifice. When the trumpets sound the signal, all the people who were within the sacrifice prostrate themselves, stretching out flat, face down, and on the ground.[citation needed]

The shofar was blown in the times of Joshua to help him capture Jericho. As they surrounded the walls, the shofar was blown and the Jews were able to capture the city.[13] The shofar was commonly taken out to war so the troops would know when a battle would begin. The person who would blow the shofar would call out to the troops from atop a hill. All of the troops were able to hear the call of the shofar from their position because of its distinct sound.[citation needed]

Post-Biblical times[]

While the shofar is best known nowadays for its use on Rosh Hashana, it also has a number of other ritual uses. It is blown each morning during the month of Elul,[15] and to mark the end of the day of fasting on Yom Kippur, once the services have been completed in the evening.[16] In Talmudic times it was also blown to introduce Shabbat.[17] At the inception of the diaspora, during the short-lived ban on playing musical instruments, the shofar was enhanced in its use, as a sign of mourning for the destruction of the temple. The declaration of the ban's source was in fact set to the music itself as the lamentation "Al Naharoth Bavel" within a few centuries of the ban. (A full orchestra played in the temple. The ban was so that this would not be taken for granted, hence the wording of the ban, "if I forget thee O Jerusalem, over my chiefest joy...".)[citation needed] The shofar is generally no longer used for secular purposes (see a notable exception in a section further down).[18]

Halakha (Jewish law) rules that the Rosh Hashana shofar blasts may not be sounded on Shabbat, due to the potential that the ba'al tekiah (shofar sounder) may inadvertently carry it, which is in a class of forbidden Shabbat work.[19] Originally, the shofar was sounded on Shabbat in the Temple in Jerusalem. After the temple's destruction, the sounding of the shofar on Shabbat was restricted to the place where the great Sanhedrin was located. However, when the Sanhedrin ceased to exist, the sounding of the shofar on Shabbat was discontinued.[20]

Mitzvah[]

The Sages indicated that the mitzvah was to hear the sounds of the shofar. If a shofar was blown into a pit or cave, one fulfilled the mitzvah if they heard the original sound, but not if they heard the echo.[21] Thus, most modern halakhic authorities hold that hearing a shofar on the radio or the Internet would not be valid to satisfy the mitzvah because "electronically reproduced sounds do not suffice for mitzvot that require hearing a specific natural sound.... However, one should consult a competent rabbi if an unusually pressing situation arises, as some authorities believe that performing mitzvot through electronically reproduced sound is preferable to not performing them at all."[22]

According to Jewish law women and minors are exempt from the commandment of hearing the shofar blown (as is the case with any positive, time-bound commandment), but they are encouraged to attend the ceremony.

If the ba'al tekiah (shofar sounder) blows with the intention that all who hear will perform the mitzvah, then anyone listening—even someone passing by—who intends to hear the Shofar can perform the mitzvah because the community blower blows for everybody. If the listener stands still, it is presumed he intends to hear.[23] If one hears the blast but with no intention of fulfilling the mitzvah, then the mitzvah has not been fulfilled.

Qualifications[]

The expert who blows (or "blasts" or "sounds") the shofar is termed the ba'al tokeah or ba'al tekiah (lit. "master of the blast"). Being a ba'al tekiah is an honor. Every male Jew is eligible for this sacred office, providing he is acceptable to the congregation. The one who blows the shofar on Rosh Hashanah should be learned in the Torah and shall be God-fearing.

The Shulchan Aruch discusses who is fit to blow the shofar on behalf of a congregation:

- Anyone not obligated to fulfill the mitzvah of sounding the shofar cannot fulfill the commandment for (cover) another whose duty it is to perform the mitzvah.

- Although a woman (who is exempt from this mitzvah because it is time-bound) may not blow the shofar for men (whose duty it is to perform the mitzvah), a woman may intone the shofar for herself and other women. Similarly, she may say a blessing over the mitzvah even though it is not mandatory (the requisite blessing contains the words "asher kid'shanu b'mitzvotav v'tzivanu", "who sanctified us with His commandments [mitzvot] and commanded us to ...", but women are not commanded in this mitzvah).

- Only a freeman (not even a slave who will become free in the next month) can be a Ba'al Tekiah.[24]

Shape and material[]

Choice of animal[]

According to the Talmud, a shofar may be made from the horn of any animal from the Bovidae family except that of a cow,[25] although a ram is preferable.[26] Bovidae horns are made of a layer of keratin (the same material as human toenails and fingernails) around a core of bone, with a layer of cartilage in between, which can be removed to leave the hollow keratin horn. An antler, on the other hand, is made of solid bone, so an antler cannot be used as a shofar because it cannot be hollowed out.

There is no requirement for ritual slaughter (shechita). Theoretically, the horn can come from a non-kosher animal, because under most (but not all) interpretations of Jewish law, the shofar is not required to be muttar be-fikha ('permissible in your mouth'); the mitzvah is hearing the shofar, not eating the animal it came from.[27] The shofar falls into the category of tashmishei mitzvah – objects used to perform a mitzvah that do not themselves have inherent holiness.[28] Moreover, because horn is always inedible, it is considered afra be-alma ('mere dust') and not an unkosher substance.[29]

The Elef Hamagen (586:5) delineates the order of preference: 1) curved ram; 2) curved other sheep; 3) curved other animal; 4) straight—ram or otherwise; 5) non-kosher animal; 6) cow. The first four categories are used with a bracha (blessing), the fifth without a bracha, and the last, not at all.[30]

A Dall Sheep with horns.

Greater Kudu, Namibia.

Construction[]

In practice two species are generally used: the Ashkenazi and Sefardi shofar is made from the horn of a domestic ram, while a Yemeni shofar is made from the horn of a kudu. A Moroccan shofar is flat, with a single, broad curve. A crack or hole in the shofar affecting the sound renders it unfit for ceremonial use. A shofar may not be painted in colors, but it may be carved with artistic designs.[31] Shofars (especially the Sephardi shofars) are sometimes plated with silver across part of their length for display purposes, although this invalidates them for use in religious practices.

The horn is flattened and shaped by the application of heat, which softens it. A hole is made from the tip of the horn to the natural hollow inside. It is played much like a European brass instrument, with the player blowing through the hole while buzzing the lips, causing the air column inside to vibrate. Sephardi shofars usually have a carved mouthpiece resembling that of a European trumpet or French horn, but smaller. Ashkenazi shofars do not.

Because the hollow of the shofar is irregular in shape, the harmonics obtained when playing the instrument can vary: rather than a pure perfect fifth, intervals as narrow as a fourth, or as wide as a sixth may be produced.

A small shofar made from a ram's horn.

A shofar made from the horn of a Greater kudu.

A small shofar made from a ram's horn.

Use in modern Jewish prayer[]

The shofar is used mainly on Rosh Hashanah. It is customary to blow the shofar 100 or 101 times on each day of Rosh Hashanah; however, halakha only requires that it be blown 30 times. The various types of blast are known as tekiah, shevarim, and teruah. The 30 required blasts consist of the sequences tekiah-shevarim-teruah-tekiah, tekiah-shevarim-tekiah, tekiah-teruah-tekiah, each sequence repeated three times.

The shofar is also blown in synagogue at the conclusion of Yom Kippur. Some only blow a tekiah gedolah; others blow tekiah-shevarim-teruah-tekiah.

Because of its inherent ties to the Days of Repentance and the inspiration that comes along with hearing its piercing blasts, the shofar is also blown after morning services for the entire month of Elul, the last month of the Jewish civil year, preceding Rosh Hashana. It is not blown on the last day of Elul, however, to mark the difference between the voluntary blasts of the month and the mandatory blasts of Rosh Hashana. Shofar blasts are also used during penitential rituals such as Yom Kippur Katan and optional prayer services called during times of communal distress. The exact modes of sounding can vary from location to location.

In an effort to improve the skills of shofar blowers, an International Day of Shofar Study is observed on Rosh Chodesh Elul, the start of the month preceding Rosh Hashanah.[32]

A Jewish Haredi man blowing a Shofar, 2012

Hasidic Jew, blowing the kudu shofar in Uman, Ukraine, 2010

A Jewish Israeli man blows the shofar at the Western Wall, Jerusalem.

Non-religious usage[]

National liberation[]

During the Ottoman and the British rule of Jerusalem, Jews were not allowed to sound the shofar at the Western Wall. After the Six-Day War, Rabbi Shlomo Goren famously approached the Wall and sounded the shofar. This fact inspired Naomi Shemer to add an additional line to her song "Jerusalem of Gold", saying, "a shofar calls out from the Temple Mount in the Old City."[33]

The Shofar has been sounded as a sign of victory and celebration. Jewish elders were photographed blowing multiple shofars after hearing that the Nazis surrendered on May 8, 1945. The shofar has played a major role in the pro-Israel movement and often played in the Salute to Israel Parade and other pro-Israel demonstrations.

Non-religious musical usage[]

In pop music, the shofar is used by the Israeli Oriental metal band Salem in their adaptation of "Al Taster" (Psalm 27). The late trumpeter Lester Bowie played a shofar with the Art Ensemble of Chicago. In the film version of the musical Godspell, the first act opens with cast member David Haskell blowing the shofar. In his performances, Israeli composer and singer Shlomo Gronich uses the shofar to produce a very wide range of notes.[34] Since 1988 Rome-based American composer Alvin Curran's project Shofar features the shofar as a virtuoso solo instrument and in combination with sets of natural and electronic sounds. Madonna used a shofar played by on the Confessions Tour and the album Confessions on a Dance Floor for the song "Isaac", based on Im Nin'alu. In 2003, The Howard Stern Show featured a contest called "Blow the Shofar", which asked callers to correctly identify popular songs played on the shofar. Additionally, Stern Show writer Benjy Bronk has repeatedly used a shofar in his antics.[35] The shofar is sometimes used in Western classical music. Edward Elgar's oratorio The Apostles includes the sound of a shofar, although other instruments, such as the flugelhorn, are usually used instead.

The shofar has been used in a number of films, both as a sound effect and as part of musical underscores. Elmer Bernstein incorporated the shofar into several cues for his score for Cecil B. DeMille's The Ten Commandments; one of the shofar calls recorded by Bernstein was later reused by the sound editors for Return of the Jedi for the Ewoks' horn calls. Jerry Goldsmith's scores to the films Alien and Planet of the Apes also incorporate the shofar in their orchestration.

See also[]

- Adhan, the Islamic call to prayer

- Church bells

- Conch (instrument)

- Erkencho

- Shankha

- Shofar blowing

Notes[]

- ^ "Jewish prayer-book". Cambridge Digital Library. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ^ Psalm 81:3 (4)

- ^ Leviticus 25:9

- ^ Hebrew: זכרון תרועה, lit. 'zikron teruˁah', Leviticus 23:24

- ^ Hebrew: יום תרועה, lit. 'yom teruˁah', Numbers 29:1

- ^ Joshua 6:4; Judges 3:27; 7:16, 20

- ^ 2 Samuel 6:15; 1 Chronicles 15:28

- ^ Psalm 98:6; compare Psalm 47:5

- ^ Psalm 150:3

- ^ Sidney B. Hoenig, "Origins of the Rosh Hashanah Liturgy", The Jewish Quarterly Review, New Series, Vol. 57, The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary Volume of the Jewish Quarterly Review (1967), pp. 312–331. • Published by University of Pennsylvania Press. Accessed 31 December 2009

- ^ Mishnah Rosh Hashana 3:3

- ^ Mishnah Rosh Hashana 3:4

- ^ Joshua 6

- ^ It has been said that when the Mashiach comes, the Sephardic community will be ready to anoint him and blow the shofar to announce his arrival. Legend has it there is a tunnel from under the Yohanan Ben Zakkai synagogue that leads directly to the Temple Mount.

- ^ Kitzur Shulchan Aruch 128:2

- ^ Kitzur Shulchan Aruch 133:26

- ^ Shabbat 35b

- ^ Judith Kaplan Eisenstein, Heritage of Music, New York: UAHC, 1972, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Rosh Hashanah 29b

- ^ Kieval, The High Holy Days, p. 114

- ^ Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 3:5; Mishnah Berurah 587:1–3

- ^ "Fulfilling Mitzvot Through Electronic Hearing Devices", Chaim Jachter and Ezra Frazer, Gray Matter volume 2 pp. 237–244. ISBN 1-933143-10-X

- ^ Mishnah Berurah 590:9

- ^ Shulchan Aruch, Orach Chaim 589:1–6

- ^ Rosh Hashanah, 26a. Although Maimonides ruled differently (Mishneh Torah Hilchot Shofar 1:1: "…the shofar with which they make the blast, whether on Rosh Hashanah or the Yovel, is the curved horn of sheep. Now all [other] horns are invalid, except the horn of a sheep…"), the custom of Israel was to make use of other horns, and not only that of the ram (the male sheep). Some would use the horn of the wild goat (Walia ibex) on Rosh Hashanah, while others made use of the long, spiraling horn of the kudu antelope because of its deep, reverberating sound. Compare the teaching of Rabbi Isaac b. Judah ibn Giat, who wrote: "All shofars are valid, excepting that of a cow since it is a [solid] horn. Said Rabbi Levi: 'The shofar of Rosh Hashanah and of Yom Kippurim are curved, while those of the entire year are straight, and thus is the Halacha.' Why is it that they blow with a shofar of a ram on Rosh Hashanah? Said the Holy One, blessed be He: 'Blow before me the shofar of a ram so that I might remember on your behalf the binding of Isaac the son of Abraham, and I impute it over you as if you had bound yourselves before me.'..." (Rabbi Isaac ibn Giat, Sefer Shaarei Simchah (Me'ah She'arim), vol. 1, Firta 1861, p. 32 [Hebrew])

- ^ Mishnah Berurah 586:1

- ^ Navon, Mois (2001). "The Ḥillazon and the Principle of "Muttar be-Fikha"" (PDF). The Torah U-Madda Journal. 10/2001: 142–162. Retrieved 15 June 2016. see pages 147-148 ff.

- ^ Megillah 26b

- ^ Avot 67b

- ^ Elef Hamagen, Rabbi Shemarya Hakreti, edited by Aharon Erand, Jerusalem: Mekitzei Nirdamim, 2003

- ^ Shulkhan Arukh, Orach Chayim 586:17

- ^ International Day of Shofar Study

- ^ Jerusalem of Gold Archived 29 November 1999 at the Wayback Machine accessed 9 December 2008

- ^ The Abraham Fund Initiatives: Press Clips - Crossing the Middle Eastern Tightrope Archived 9 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ From ‘Star Wars’ To Madonna: 7 Times Shofars Showed Up Outside Shul

References[]

- Arthur L. Finkle, Easy Guide to Shofar Sounding, Los Angeles: Torah Aura, 2003

- Hearing Shofar: The Still Small Voice of the Ram's Horn by Michael T. Chusid, a three volume compendium of shofar information.

Further reading[]

- Arthur l. Finkle, Shofar Sounders Reference Manual at the Wayback Machine (archived 26 October 2009), LA: Torah Aura, 1993

- Montagu, Jeremy. 2016. The Shofar: Its History and Usage. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers.

External links[]

Media related to Shofars at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Shofars at Wikimedia Commons- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Shulkhan Arukh limited English translation includes Rosh Hashanah chapters 585–590 regarding the shofar.

- Shofar sounds several videos with shofar sounds and explanations

- biblicaltrumpets.org - A research site on the use of trumpets in both Old and New Testament.

- The origins of the Shofar - Ajudaica 101

- Elul

- Ancient Hebrew musical instruments

- Natural horns and trumpets

- Hebrew words and phrases

- High Holy Days

- Jewish ritual objects

- Rosh Hashanah

- Israeli musical instruments

- Animal products

- Jewish symbols

- Hebrew words and phrases in the Hebrew Bible

- Hebrew words and phrases in Jewish law

- Hornpipes

- Sacred musical instruments