Sleep debt

Sleep debt or sleep deficit is the cumulative effect of not getting enough sleep. A large sleep debt may lead to mental or physical fatigue.

There are two kinds of sleep debt: the results of partial sleep deprivation and total sleep deprivation. Partial sleep deprivation occurs when a person or a lab animal sleeps too little for several days or weeks. Total sleep deprivation means being kept awake for at least 24 hours. There is debate in the scientific community over the specifics of sleep debt, and it is not considered to be a disorder.[citation needed]

Phosphorylation of proteins[]

In mice there are 80 proteins in the brain, called "sleep need index phosphoproteins" (SNIPPs), which become more and more phosphorylated during waking hours, and are dephosphorylated during sleep. The phosphorylation is aided by the gene Sik3. A type of Laboratory mouse called Sleepy with an altered version of this protein (called SLEEPY) which is more active than the regular version, resulting in the mice showing more slow-wave activity during non-REM sleep, which is the best measurable index of sleep need known. Inhibition of the Sik3 gene decreases phosphorylation and slow-wave activity in both normal and modified mice.[2]

Physiological effects of sleep debt[]

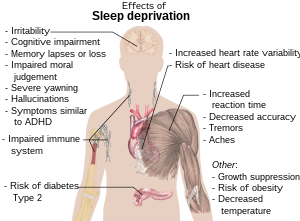

Chronic sleep debt has a substantial health impact on the human body, specifically on metabolic and endocrine functions.[3] A study published in The Lancet investigated the physiological effects of sleep debt by assessing the sympathovagal balance (an indicator of the sympathetic nervous system activity), thyrotropic function, HPA axis activity as well as the carbohydrate metabolism of 11 young adult males whose sleep period for six nights was either restricted to four hours per night or extended to 12 hours in bed per night.[4] Results revealed that in the sleep-debt condition, thyrotropin concentrations were decreased while lowered glucose and insulin responses indicated a clear impairment of carbohydrate tolerance, a 30% decrease than in the well-rested sleep condition.[4] On the other hand, males who were sleep-restricted showed significantly elevated concentrations of evening cortisol (the "stress" hormone) and elevated sympathetic nervous system activity in comparison to those who enjoyed a full sleep, over a period of 6 nights.[4][5] Chronic sleep debt has a detrimental impact on human (neuro)physiological functioning and can disrupt immune, endocrine and metabolic function while increasing the severity of cardiovascular and age-related illnesses over a period of time.[4]

Neuropsychological effects of sleep debt on emotions[]

Accumulated and continuous short-term sleep deficit has been shown to increase and intensify psychophysiological reactions in humans to emotional stimuli.[6] The amygdala plays a strong functional role in the expression of negative emotions such as fear, and through its anatomical connections with the medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) has an important function in subjective suppression of and the reframing and reappraisal of negative emotions.[6] A study assessing sleep deficit in young Japanese men over a 5-day period during which they slept only 4 hours per day showed that there was greater left amygdala activation to fearful faces but not happy faces, and an overall subjective mood deterioration.[6] As a result, even short-term continuous sleep debt, or deprivation, has been shown to reduce this functional relationship between the amygdala and mPFC, inducing negative mood changes through increased fear and anxiety to unpleasant emotional stimuli and events.[7] Thus, a full and uninterrupted 7-hour sleep is crucial for the proper functioning of the amygdala in modulating an individual's mood states by reducing negative emotional intensities and increasing reactivity to positive emotional stimuli.[6]

Sleep debt and obesity[]

Epidemiological research has solidified the association between sleep debt and/or deprivation and obesity as a result of an elevated body mass index (BMI) through various ways such as disruptions in the hormones leptin and ghrelin that regulate appetite, higher food consumption and poor diets, and a decrease in overall calorie burning.[5] However, in recent years, multimedia usage such as Internet and television consumption that play an active role in sleep deficit has also been linked to obesity by provoking unhealthy, sedentary lifestyles and habits as well as higher food consumption.[5] Moreover, work-related behaviors such as long working and commuting hours and irregular work timings such as during shift work also function as contributing factors to being overweight or obese as a result of shorter sleeping periods.[5] In comparison to adults, children exhibit a more consistent association between sleep debt and obesity.[5]

Sleep debt and mortality[]

Several studies have shown that sleep duration, specifically sleep deficit or shorter sleep duration, has an effect on mortality, whether it be weekdays or weekends.[8] In people aged 65 years and younger, a daily sleep duration of 5 hours or less (amounting to a sleep deficit of 2 hours per day) during weekends correlated with a 52% higher mortality rate compared to a control group who slept for 7 hours.[8] Consistent weekday sleep debt exhibited a detrimental association with mortality and morbidity, but this effect was negated when compensated with long sleep during weekends.[8][9] However, the harmful consequences of sleep debt over weekdays and weekends was not seen in individuals aged 65 years and older.[8]

Scientific debate[]

There is debate among researchers as to whether the concept of sleep debt describes a measurable phenomenon. The September 2004 issue of the journal Sleep contains dueling editorials from two leading sleep researchers, David F. Dinges[10] and Jim Horne.[11] A 1997 experiment conducted by psychiatrists at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine suggested that cumulative nocturnal sleep debt affects daytime sleepiness, particularly on the first, second, sixth, and seventh days of sleep restriction.[12]

In one study, subjects were tested using the psychomotor vigilance task (PVT). Different groups of people were tested with different sleep times for two weeks: 8 hours, 6 hours, 4 hours, and total sleep deprivation. Each day they were tested for the number of lapses on the PVT. The results showed that as time went by, each group's performance worsened, with no sign of any stopping point. Moderate sleep deprivation was found to be detrimental; people who slept 6 hours a night for 10 days had similar results to those who were completely sleep deprived for 1 day.[13][14]

Evaluation[]

Sleep debt has been tested in a number of studies through the use of a sleep onset latency test.[15] This test attempts to measure how easily a person can fall asleep. When this test is done several times during a day, it is called a multiple sleep latency test (MSLT). The subject is told to go to sleep and is awakened after determining the amount of time it took to fall asleep. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS), an eight item questionnaire with scores ranging from 0 to 24, is another tool used to screen for potential sleep debt.

A January 2007 study from Washington University in St. Louis suggests that saliva tests of the enzyme amylase could be used to indicate sleep debt, as the enzyme increases its activity in correlation with the length of time a subject has been deprived of sleep.[16][17]

The control of wakefulness has been found to be strongly influenced by the protein orexin. A 2009 study from Washington University in St. Louis has illuminated important connections between sleep debt, orexin, and amyloid beta, with the suggestion that the development of Alzheimer's disease could hypothetically be a result of chronic sleep debt or excessive periods of wakefulness.[18]

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Reference list is found on image page in Commons: Commons:File:Effects of sleep deprivation.svg#References

- ^ Wang Z, Ma J, Miyoshi C, Li Y, Sato M, Ogawa Y, et al. (June 2018). "Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis of the molecular substrates of sleep need". Nature. 558 (7710): 435–439. Bibcode:2018Natur.558..435W. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0218-8. PMC 6350790. PMID 29899451.

- ^ Leproult, Rachel; Van Cauter, Eve (2009), Loche, S.; Cappa, M.; Ghizzoni, L.; Maghnie, M. (eds.), "Role of Sleep and Sleep Loss in Hormonal Release and Metabolism", Endocrine Development, KARGER, 17: 11–21, doi:10.1159/000262524, ISBN 978-3-8055-9302-1, PMC 3065172, PMID 19955752

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Spiegel K, Leproult R, Van Cauter E (October 1999). "Impact of sleep debt on metabolic and endocrine function". Lancet. 354 (9188): 1435–9. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(99)01376-8. PMID 10543671. S2CID 3854642.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Bayon V, Leger D, Gomez-Merino D, Vecchierini MF, Chennaoui M (August 2014). "Sleep debt and obesity". Annals of Medicine. 46 (5): 264–72. doi:10.3109/07853890.2014.931103. PMID 25012962. S2CID 36653608.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Motomura Y, Kitamura S, Oba K, Terasawa Y, Enomoto M, Katayose Y, Hida A, Moriguchi Y, Higuchi S, Mishima K (2013). "Sleep debt elicits negative emotional reaction through diminished amygdala-anterior cingulate functional connectivity". PLOS ONE. 8 (2): e56578. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...856578M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0056578. PMC 3572063. PMID 23418586.

- ^ Minkel JD, Banks S, Htaik O, Moreta MC, Jones CW, McGlinchey EL, et al. (October 2012). "Sleep deprivation and stressors: evidence for elevated negative affect in response to mild stressors when sleep deprived". Emotion. 12 (5): 1015–20. doi:10.1037/a0026871. PMC 3964364. PMID 22309720.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Åkerstedt T, Ghilotti F, Grotta A, Zhao H, Adami HO, Trolle-Lagerros Y, Bellocco R (February 2019). "Sleep duration and mortality - Does weekend sleep matter?". Journal of Sleep Research. 28 (1): e12712. doi:10.1111/jsr.12712. PMC 7003477. PMID 29790200.

- ^ Grandner, Michael A.; Hale, Lauren; Moore, Melisa; Patel, Nirav P. (June 2010). "Mortality associated with short sleep duration: The evidence, the possible mechanisms, and the future". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 14 (3): 191–203. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2009.07.006. PMC 2856739. PMID 19932976.

- ^ Dinges DF (September 2004). "Sleep debt and scientific evidence". Sleep. 27 (6): 1050–2. PMID 15532196.

- ^ Horne J (September 2004). "Is there a sleep debt?". Sleep. 27 (6): 1047–9. PMID 15532195.

- ^ Dinges DF, Pack F, Williams K, Gillen KA, Powell JW, Ott GE, et al. (April 1997). "Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 hours per night". Sleep. 20 (4): 267–77. PMID 9231952.

- ^ Walker, M.P. (2009, October 21). *Sleep Deprivation III: Brain consequences – Attention, concentration and real life.* Lecture given in Psychology 133 at the University of California, Berkeley, CA.

- ^ Knutson KL, Spiegel K, Penev P, Van Cauter E (June 2007). "The metabolic consequences of sleep deprivation". Sleep Medicine Reviews. 11 (3): 163–78. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.01.002. PMC 1991337. PMID 17442599.

- ^ Klerman EB, Dijk DJ (October 2005). "Interindividual variation in sleep duration and its association with sleep debt in young adults". Sleep. 28 (10): 1253–9. doi:10.1093/sleep/28.10.1253. PMC 1351048. PMID 16295210.

- ^ Fisher M. "Sleeping well isn't easy, but it doesn't have to be hard either". supplementyoursleep.com. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- ^ "First Biomarker for Human Sleepiness Identified". Washington University in St. Louis. January 25, 2007.

- ^ Kang JE, Lim MM, Bateman RJ, Lee JJ, Smyth LP, Cirrito JR, et al. (November 2009). "Amyloid-beta dynamics are regulated by orexin and the sleep-wake cycle". Science. 326 (5955): 1005–7. Bibcode:2009Sci...326.1005K. doi:10.1126/science.1180962. PMC 2789838. PMID 19779148.

Further reading[]

- Dement WC (1999). The Promise of Sleep. New York: Delacorte Press, Random House Inc.

External links[]

- Sleeplessness and sleep deprivation

- Sleep physiology

- Sleep medicine

- Sleep disorders