Social history of Postwar Britain (1945–1979)

| 8 May 1945 – 3 May 1979 | |

The Beatles, a band originating from Liverpool who became synonyms with the cultural changes of the 1960s, arrive in New York in 1964. | |

| Preceded by | Second World War |

|---|---|

| Followed by | Modern Era |

| Monarch(s) |

|

| Leader(s) |

|

| History of the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

|

|

| Periods in English history |

|---|

|

| Timeline |

The social history of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1979 began with the aftermath of the Second World War. The United Kingdom was one of the victors, but victory was costly in social and economic terms. Thus, the late 1940s was a time of austerity and economic restraint, which gave way to prosperity in the 1950s. The Labour Party, led by wartime Deputy Prime Minister Clement Attlee, won the 1945 postwar general election in an unexpected landslide and formed their first ever majority government. Labour governed until 1951, and granted independence to India in 1947. Most of the other major overseas colonies became independent in the late 1950s and early 1960s. The UK collaborated closely with the United States during the Cold War after 1947, and in 1949; helped to form NATO as a military alliance against the spread of Soviet Communism. After a long debate and initial scepticism, the United Kingdom joined the European Economic Community along with the Republic of Ireland and Denmark on 1 January 1973. Immigration from the British Empire and Commonwealth laid the foundations for the multicultural society in today's Britain, while traditional Anglican and other denominations of Christianity declined.

Prosperity returned in the 1950s, reaching the middle class and, to a large extent, the working class across Britain. London remained a world centre of finance and culture, but the nation was no longer a superpower. In foreign policy, the UK promoted the Commonwealth (in the economic sphere) and the Atlantic Alliance (in the military sphere). In domestic policy, a post-war consensus saw the leadership of the Labour and Conservative parties largely agreed on Keynesian policies, with support for trade unions, regulation of business, and nationalisation of many older industries. The discovery of North Sea oil eased some financial pressures, but the 1970s saw slow economic growth, rising unemployment, and escalating labour strife. Deindustrialisation or the loss of heavy industry, especially coal mining, shipbuilding and manufacturing, grew worse after 1970 as the British economy shifted to services. London and the South East maintained prosperity, as London became the leading financial centre in Europe and played a major role in world affairs.

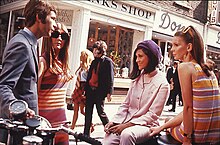

Substantial educational reform took place in this period with developments including increases to the school leaving age, the introduction of the modern day split between primary and secondary school and the expansion and later largely dismantling of the grammar school system. Liberalising social reforms took place in areas such as abortion, divorce, LGBT rights and the death penalty. The status of women slowly improved. A youth culture emerged from the 1960s with such iconic international celebrities as The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

Post-war era[]

Age of Austerity[]

In May 1945 the governing coalition dissolved, triggering the long-overdue 1945 general election.[1] Labour won just under 50% of the vote and a majority of 145 seats.[2] The new Prime Minister Clement Attlee proclaimed, "This is the first time in the history of the country that a labour movement with a socialist policy has received the approval of the electorate."[3]

During the war, surveys showed public opinion moving to the left and in favour of wide social reform.[4] The public associated the Conservative Party with the poverty and mass unemployment of the inter-war years.[5] Historian Henry Pelling, noting that polls showed a steady Labour lead after 1942, points to the usual swing against the party in power; the Conservative loss of initiative; wide fears of a return to the high unemployment of the 1930s; the theme that socialist planning would be more efficient in operating the economy; and the mistaken belief that Churchill would continue as prime minister regardless of the result.[6] The sense that all Britons had joined in a "People's War" and all deserved a reward animated voters.[7]

As the war ended and American Lend Lease suddenly and unexpectedly ended,[8] the Treasury was near bankruptcy and Labour's new programmes would be expensive.[citation needed] The economy did not reach prewar levels until the 1950s. Due to continued and increased rationing, the immediate post-war years were called the Age of Austerity, (not to be confused with the 21st-century Age of Austerity).[9][citation needed]

The war almost bankrupted Britain, while the country maintained a global empire in an attempt to remain a global power.[10] It operated a large air force and a conscript army.[11] Without Lend Lease, bankruptcy loomed. The government secured a low-interest $3.75 billion loan from the US in December 1945.[12] Rebuilding necessitated fiscal austerity in order to maximise export earnings, while Britain's colonies and other client states were required to keep their reserves in pounds as "sterling balances".[13] An additional $3.2 billion – which did not have to be repaid – came from the American Marshall Plan in 1948–52. However the Plan did require Britain to modernise its business practices and remove trade barriers. Britain was an enthusiastic supporter of the Marshall Plan and used it as a lever to more directly promote European unity.[14] Britain was an enthusiastic cofounder of the NATO military alliance formed in 1949 against the Soviets.[15]

Rationing, especially of food, continued in the post-war years as the government tried to control demand and normalise the economy.[16] Anxieties were heightened when the country suffered one of the worst winters on record in 1946–47: the coal and railway systems failed, factories closed, and a large proportion of the population suffered due to the cold.[17]

Rationing[]

Wartime rationing continued and was for the first time extended to bread in order to feed the German civilians in the British sector of occupied Germany.[18] During the war the government had banned ice cream and had rationed sweets such as chocolates and confections; all sweets were rationed until 1954.[19] Rationing was beneficial for many of the poor because their rationed diet was of greater nutritional value than their pre-war diet. Housewives organised to oppose the austerity.[20] The Conservatives gained support by attacking socialism, austerity, rationing and economic controls and returned to power in 1951.[21]

Morale was boosted by the marriage of Princess Elizabeth to Philip Mountbatten in 1947,[22] and by the 1948 Summer Olympics held in London.[23] Reconstruction had begun in London but no funding was available for new facilities.[24]

Welfare state[]

The most important Labour initiatives were the expansion of the welfare state, the founding of the National Health Service and nationalisation of the coal, gas, electricity, railways and other primary industries. The welfare state was expanded by the National Insurance Act 1946, which built upon the comprehensive system of social security originally set up in 1911.[25] People of working age had to pay a weekly contribution (by buying a stamp) and in return were entitled to a wide range of benefits, including a pension, health and unemployment benefits, and widows' benefits.[26]

The National Health Service began operations in July 1948.[27] It promised to give cradle to grave free hospital and medical care for everyone in the country, regardless of income. Labour went on to expand low cost council housing for the poor.[28]

The Treasury, headed by Chancellor of the Exchequer Hugh Dalton, faced urgent problems. Half of the wartime economy had been devoted to mobilising soldiers, warplanes, bombs and munitions; a transition to a peacetime budget was begun while attempting to control inflation.[29] New loans from the US and Canada to replace Lend Lease were essential to sustain living conditions.[30]

Housing[]

Housing was a critical shortage.[31] Air raids had destroyed half a million housing units; upgrades and repairs on undamaged units had been postponed.[32] Three-quarters of a million new dwellings were needed.[33] The government aimed for 300,000 annually,[34] compared to the maximum prewar rate of 350,000. However, shortages of builders, materials,[35] and money limited progress.[30] Not counting 150,000 temporary prefabricated units, the shortage reached 1,500,000 units by 1951.[36] Legislation kept rents down[37] but did not lead to an increase in the number of new homes. The ambitious New Towns project did not provide enough units.[38] The Conservatives made housing a high priority and oversaw the building of 2,500,000 new units, two-thirds of them through local councils. Haste made for dubious quality and policy increasingly shifted towards renovation of existing properties rather than the construction of new ones. Slums were cleared, opening the way for gentrification in the inner cities.[39]

Nationalisation[]

Martin Francis argues there was Labour Party consensus by 1945, both on the National Executive Committee and at party conferences, on a definition of socialism that stressed moral as well as material improvement. The Attlee government was committed to rebuilding British society as an ethical commonwealth, using public ownership and controls to abolish extremes of wealth and poverty. Labour's ideology contrasted sharply with the contemporary Conservative Party's defence of individualism, inherited privileges, and income inequality.[40]

Attlee's government nationalised major industries and utilities. It developed and implemented the "cradle to grave" welfare state conceived by liberal economist William Beveridge. The creation of Britain's publicly funded National Health Service under health minister Aneurin Bevan remains Labour's proudest achievement.[41]

However the Labour Party had developed no detailed nationalization plans.[42] Improvising, they started with the Bank of England, civil aviation, coal and Cable & Wireless. Then came railways, canals, road haulage and trucking, electricity, and gas. Finally came iron and steel, which was a special case because it was a manufacturing industry. Altogether, about one fifth of the economy was taken over. Labour dropped the notion of nationalising farms.

On the whole nationalisation went smoothly, with two exceptions. Nationalising hospitals was strongly opposed by practising physicians. Compromises allowed them also to have a private practice, and the great majority decided to work with the National Health Service. Much more controversial was the nationalisation of the iron and steel industry — unlike coal, it was profitable and highly efficient. Nationalisation was opposed by industry owners and executives, the business community as a whole and the Conservative Party as a whole. The House of Lords was also opposed, but the Parliament Act 1949 reduced its power to delay legislation to just one year. Finally in 1951, iron and steel were nationalised, but then Labour lost its majority. The Conservatives in 1955 returned them to private ownership.[43]

The procedure used was developed by Herbert Morrison, who as Lord President of the Council chaired the Committee on the Socialisation of Industries. He followed the model that was already in place of setting up public corporations such as the BBC in broadcasting (1927). The owners of corporate stock were given government bonds and the government took full ownership of each affected company, consolidating it into a national monopoly. The managers remained the same, only now they became civil servants working for the government. For the Labour Party leadership, nationalisation was a way to consolidate economic planning. It was not designed to modernise old industries, make them efficient, or transform their organisational structure. There was no money for modernisation, although the Marshall Plan, operated separately by American planners, did force many British businesses to adopt modern managerial techniques. Hard line British Marxists were fervent believers in dialectical materialism and in fighting against capitalism and for workers' control, trade unionism, nationalisation of industry and centralized planning. They were now disappointed, as the nationalised industries seemed identical to the old private corporations, and national planning was made virtually impossible by the government's financial constraints. At Oxford a "New Left" started to emerge that rejected old-line approaches.[44] Socialism was in place, but it did not seem to make a major difference. Rank-and-file workers had long been motivated to support Labour by tales of the mistreatment of workers by foremen and management. The foremen and the managers were the same people as before, with much the same power over the workplace. There was no worker control of industry. The unions resisted government efforts to set wages. By the time of the general elections in 1950 and 1951, Labour seldom boasted about its nationalisations. Instead Conservatives decried the inefficiency and mismanagement, and promised to reverse the treatment of steel and trucking.[45][46]

Labour weaknesses[]

Labour struggled to maintain its support. Realising the unpopularity of rationing, in 1948–49 the government ended the rationing of potatoes, bread, shoes, clothing and jam, and increased the petrol ration for summer drivers. However, meat was still rationed, and in very short supply, at high prices.[47] Militant socialist Aneurin Bevan, the Minister of Health, said at a party rally in 1948, "no amount of cajolery... can eradicate from my heart a deep burning hatred for the Tory Party.... They are lower than vermin." Bevan, a coal miner's son, had gone too far in a land that took pride in self-restraint, and he never lived down the remark.[48]

Labour narrowly won the 1950 general election with a majority of five seats. Defence became one of the divisive issues for Labour itself, especially defence spending, which reached 14% of GDP in 1951 during the Korean War. These costs strained public finances. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, Hugh Gaitskell, introduced prescription charges for NHS dentures and spectacles, leading Bevan, along with Harold Wilson (President of the Board of Trade) to resign. A decade of turmoil ensued in the Party, much to the advantage of the Conservatives who won again and again by ever larger majorities.[49]

David Kynaston argues that the Labour Party under Attlee was led by conservative parliamentarians who always worked through constitutional parliamentary channels; they saw no need for large demonstrations, boycotts or symbolic strikes. The result was a solid expansion and coordination of the welfare system, most notably the concentrated and centralised NHS. Private sector nationalisation focused on older, declining industries, most notably coal mining. Labour kept promising systematic economic planning, but never established adequate mechanisms. Much of the planning was forced upon them by the Marshall Plan, which insisted on a modernisation of business procedures and government regulations.[50] The Keynesian model accepted by Labour emphasised that planning could be handled indirectly through national spending and tax policies.[51]

Cold War[]

Britain faced severe financial constraints, lacking cash for needed imports. It responded by reducing its international entanglements as in Greece, and by sharing the hardships of an "age of austerity".[52] Early fears that the US would veto nationalisation or welfare policies proved groundless.[53]

Under Attlee foreign policy was the domain of Ernest Bevin, who looked for innovative ways to bring western Europe together in a military alliance. One early attempt was the Dunkirk Treaty with France in 1947.[54] Bevin's commitment to the West European security system made him eager to sign the Treaty of Brussels in 1948. It drew Britain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg into an arrangement for collective security, opening the way for the formation of NATO in 1949. NATO was primarily aimed as a defensive measure against Soviet expansion, while helping bring its members closer together and enabled them to modernise their forces along parallel lines, also encouraging arms purchases from Britain.[55]

Bevin began the process of dismantling the British Empire when it granted independence to India and Pakistan in 1947, followed by Burma (Myanmar) and Ceylon (Sri Lanka) in 1948.[56] In January 1947, the government decided to proceed with the development of Britain's nuclear weapons programme, primarily to enhance Britain's security and also its status as a superpower. A handful of top elected officials made the decision in secret, ignoring the rest of the cabinet, in order to forestall the Labour Party's pacifist and anti-nuclear wing.[57]

Return of Churchill[]

In the late 1940s the Conservative Party exploited and incited growing public anger at food rationing, scarcity, controls, austerity and omnipresent government bureaucracy. They used the dissatisfaction with their opponent's socialist and egalitarian policies to rally middle-class supporters and score a political victory at the 1951 general election. Their appeal was especially effective to housewives, who faced more difficult shopping conditions after the war than during it.[58]

The Labour Party kept slipping, interrupted by good moments such as the Festival of Britain in summer 1951, a national exhibition and fair held throughout the country. Historian Kenneth O. Morgan says the Festival was a "triumphant success" as every day thousands:

- flocked to the South Bank site [in London], to wander around the Dome of Discovery, gaze at the Skylon, and generally enjoy a festival of national celebration. Up and down the land, lesser festivals enlisted much civic and voluntary enthusiasm. A people curbed by years of total war and half-crushed by austerity and gloom, showed that it had not lost the capacity for enjoying itself....Above all, the Festival made a spectacular setting as a showpiece for the inventiveness and genius of British scientists and technologists.[59]

The Conservative Party restored its credibility on economic policy with the Industrial Charter written by Rab Butler, which emphasised the importance of removing unnecessary controls, while going far beyond the laissez-faire attitude of old towards industrial social problems. Churchill was party leader, but he brought in a Party Chairman to modernise the institution. Lord Woolton was a successful department store owner and wartime Minister of Food. As Party Chairman 1946–55, he rebuilt its local organisations with an emphasis on membership, money and a unified national propaganda appeal on critical issues. To broaden the base of potential candidates, the national party provided financial aid and assisted local organisations in raising local money. Lord Woolton emphasised a rhetoric that characterised the opponents as "Socialist" rather than "Labour". The libertarian influence of Professor Friedrich Hayek's 1944 best-seller Road to Serfdom was apparent in the younger generation, but that took another quarter century to have a policy impact. By 1951, Labour's factions were bitterly divided.

The Conservatives narrowly won the October 1951 election, although Labour got considerably more votes. Most of the new programmes passed by Labour were accepted by the Conservatives and became part of the "post war consensus" that lasted until the 1970s.[60] The Conservatives ended rationing and reduced controls, and sold the famous Skylon for scrap. They were conciliatory towards unions and retained nationalisation and the welfare state, while privatising the steel and road haulage industries in 1953.[61]

Golden Age[]

In the 1950s, rebuilding continued, and immigrants from Commonwealth nations, mostly from the Caribbean and the Indian subcontinent, began arriving in a steady flow. The shock of the Suez Crisis of 1956 made clear that Britain had lost its role as a superpower. It already knew it could no longer afford its large Empire. This led to decolonisation, and a withdrawal from almost all of its colonies by 1970.

In 1957 Prime Minister Macmillan boasted:[62]

Let us be frank about it: most of our people have never had it so good. Go round the country, go to the industrial towns, go to the farms and you will see a state of prosperity such as we have never had in my lifetime – nor indeed in the history of this country.

Unemployment figures[63] show that unemployment was significantly lower during the Golden Age than before or after:

| Epoch | Date range | % of British labour force unemployed |

|---|---|---|

| Pre–Golden Age | 1921–1938 | 13.4 |

| Golden Age | 1950–1969 | 1.6 |

| Post–Golden Age | 1970–1993 | 6.7 |

In addition to superior economic performance, other social indexes were higher in the golden age; for example, the proportion of Britain's population saying they are "very happy" registered at 52% in 1957 but fell to just 36% in 2005.[64][65]

The 1950s and 1960s experienced continued modernisation of the economy.[66] Representative was the construction of the first motorways. Britain maintained and increased its financial role in the world economy, and used the English language to promote its educational system to students from around the globe. With relatively low unemployment during this period, the standard of living continued to rise, with new private and council housing developments increasing and the number of slum properties diminishing.

During the period, unemployment in Britain averaged only 2%. As prosperity returned after the war, Britons became more family-centred.[67] Leisure activities became more accessible to more people. Holiday camps, which had first opened in the 1930s, became popular holiday destinations in the 1950s – and people increasingly had the ability to pursue personal hobbies. The BBC's early television service was given a major boost in 1953 with the coronation of Elizabeth II, attracting a worldwide audience of twenty million, plus tens of millions more by radio. Many middle-class people bought televisions to view the event. In 1950 just 1% owned television sets; by 1965 25% did, and many more were rented. As austerity receded after 1950 and consumer demand kept growing, the Labour Party hurt itself by shunning consumerism as the antithesis of the socialism it demanded.[68]

Small neighbourhood shops were increasingly replaced by chain stores and shopping centres. Cars were becoming a significant part of British life, with city-centre congestion and ribbon developments springing up along major roads. These problems led to the idea of a green belt to protect the countryside, which was at risk from development of new housing units.[69]

The post-war period witnessed a dramatic rise in the average standard of living, with a 40% rise in average real wages from 1950 to 1965.[70][page needed] Workers in traditionally poorly paid semi-skilled and unskilled occupations saw a particularly marked improvement in their wages and living standards. Consumption, became more equal, especially as the landed gentry was pressed to pay its taxes and had to reduce its level of consumption. The rise in wages spurred consumer spending to increase by about 20% during the period, while economic growth continued at about 3%. The last food rations were ended in 1954, along with hire-purchase controls. As a result of these changes, large numbers of the working classes were able to participate in the consumer market for the first time.[71] The number one major purchase was a washing machine. Ownership jumped from 18 percent in 1955 to 29 percent in 1958 and 60 percent in 1966.[72]

Various fringe benefits became more common. In 1955, 96% of manual labourers were entitled to two weeks' holiday with pay, compared with 61% in 1951. By the end of the 1950s, Britain had become one of the world's most affluent countries, and by the early Sixties, most Britons enjoyed a level of prosperity that had previously been the privilege of only a small minority.[73] For the first time in decades, the young and unattached had spare cash for leisure, clothes and even luxuries. In 1959, Queen magazine declared that "Britain has launched into an age of unparalleled lavish living." Average wages were high while jobs were plentiful, and people saw their personal prosperity climb even higher. Prime Minister Harold Macmillan claimed that "the luxuries of the rich have become the necessities of the poor." As summed up by R. J. Unstead,

Opportunities in life, if not equal, were distributed much more fairly than ever before and the weekly wage-earner, in particular, had gained standards of living that would have been almost unbelievable in the thirties.[74]

Labour historian Martin Pugh stated:

Keynesian economic management enabled British workers to enjoy a golden age of full employment which, combined with a more relaxed attitude towards working mothers, led to the spread of the two-income family. Inflation was around 4 per cent, money wages rose from an average of £8 a week in 1951 to £15 a week by 1961, home-ownership spread from 35 per cent in 1939 to 47 per cent by 1966, and the relaxation of credit controls boosted the demand for consumer goods.[75]

By 1963, 82% of all private households had a television, 72% a vacuum cleaner, 45% a washing machine, and 30% a refrigerator. John Burnett notes that ownership had spread down the social scale so that the gap between consumption by professional and manual workers had considerably narrowed. The provision of household amenities steadily improved in the late decades of the century. From 1971–1983, households having the sole use of a fixed bath or shower rose from 88% to 97%, and those with an indoor toilet from 87% to 97%. In addition, the number of households with central heating almost doubled during that same period, from 34% to 64%. By 1983, 94% of all households had a refrigerator, 81% a colour television, 80% a washing machine, 57% a deep freezer, and 28% a tumble-drier.[76]

From a European perspective, however, the UK was not keeping pace. Between 1950–1970, it was overtaken by most of the countries of the European Common Market in terms of telephones, refrigerators, television sets, cars and washing machines per household.[77] Education grew, but not as fast as in rival nations. By the early 1980s, some 80% to 90% of school leavers in France and West Germany received vocational training, compared with 40% in the United Kingdom. By the mid-1980s, over 80% of pupils in the United States and West Germany and over 90% in Japan stayed in education until the age of eighteen, compared with barely 33% of British pupils.[78] In 1987, only 35% of 16-to-18-year-olds[where?] were in full-time education or training, compared with 80% in the United States, 77% in Japan, 69% in France, and 49% in the United Kingdom.[79]

1970s economic crises[]

In comparing economic prosperity (using gross national product per person), the British record was one of steady downward slippage from seventh place in 1950, to twelfth in 1965, to twentieth in 1975. Labour politician Richard Crossman, after visiting prosperous Canada, returned to England with a

- sense of restriction, yes, even of decline, the old country always teetering on the edge of a crisis, trying to keep up appearances, with no confident vision of the future.[80]

Economists provided four overlapping explanations. The "early start" theory said that Britain's rivals were doing so well because they were still moving large numbers of farm workers into more lucrative employment, which Britain had done in the nineteenth century. A second theory emphasised the "rejuvenation by defeat", whereby Germany and Japan had been forced to re-equip, rethink and restructure their economies. The third approach emphasised the drag of "imperial distractions", saying that responsibilities to its large empire handicapped the home economy, especially through defence spending, and economic aid. Finally, the theory of "institutional failure" stressed the negative roles of discontinuity, unpredictability, and class envy. The last theory blamed trade unions, public schools, and universities for perpetuating an elitist anti-industrial attitude.[81]

In the 1970s, the exuberance and the radicalism of the 1960s ebbed. Instead a mounting series of economic crises, including many trade union strikes, pushed the British economy further and further behind European and world growth. The result was a major political crisis, and a Winter of Discontent in the winter of 1978–79, when widespread strikes by public sector trade unions seriously inconvenienced and angered the public.[82][83]

Historians Alan Sked and Chris Cook summarise the general consensus of historians regarding Labour in power in the 1970s:

If Wilson's record as prime minister was soon felt to have been one of failure, that sense of failure was powerfully reinforced by Callaghan's term as premier. Labour, it seemed, was incapable of positive achievements. It was unable to control inflation, unable to control the unions, unable to solve the Irish problem, unable to solve the Rhodesian question, unable to secure its proposals for Welsh and Scottish devolution, unable to reach a popular modus vivendi with the Common Market, unable even to maintain itself in power until it could go to the country and the date of its own choosing. It was little wonder, therefore, that Mrs. Thatcher resoundingly defeated it in 1979.[84]

Bright spots included large deposits of oil that were found in the North Sea, allowing Britain to become a major oil exporter to Europe in the era of the 1970s energy crisis.[85]

Long term economic factors[]

While economic historians concentrate on statistical parameters, cultural historians added to the list of factors to explain Britain's long-term relative economic decline. According to Peter Hennessy, these include:

- Excessive trade union power.

- Too much nationalisation.

- Insufficient entrepreneurship.

- Too many wars, both hot and cold.

- The distraction of imperialism.

- A feeble political class.

- A weak civil service

- An enduring aristocratic tradition disparaged management.

- Weak vocational education at all levels.

- Social class rigidities interference with progress.[clarification needed][86]

Northern Ireland and the Troubles[]

In the 1960s, moderate Unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland Terence O'Neill tried to reform the system and give a greater voice to Catholics, who comprised 40% of the population of Northern Ireland. His goals were blocked by militant Protestants led by Reverend Ian Paisley.[87] The increasing pressures from nationalists for reform and from unionists for "No surrender" led to the appearance of the civil rights movement under figures such as John Hume and Austin Currie. Clashes escalated out of control, as the army could barely contain the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA) and the Ulster Defence Association. British leaders feared their withdrawal would lead to a "doomsday scenario", with widespread communal strife, followed by the mass exodus of hundreds of thousands of refugees. The UK Parliament in London shut down Northern Ireland's parliament and imposed direct rule. By the 1990s, the failure of the IRA campaign to win mass public support or achieve its aim of a British withdrawal led to negotiations that in 1998 produced what is commonly referred to as the 'Good Friday Agreement'. This won popular support and largely ended the most violent aspects of The Troubles.[88][89]

Social and cultural forces[]

Secularisation[]

In the late 1940s Britain was still a Christian nation, with its religiosity reinforced by the wartime experience. Peter Forster found that in answering pollsters, the British people reported an overwhelming belief in the truth of Christianity, a high respect for it, and a strong association between it and moral behaviour.[90] Peter Hennessy argued that long-held attitudes did not stop change; by mid-century "Britain was still a Christian country only in a vague attitudinal sense, belief generally being more a residual husk than the kernel of conviction."[91][page needed] Kenneth O. Morgan agreed, noting that "the Protestant churches, Anglican, and more especially non-conformist, all felt the pressure of falling numbers and of secular challenges.... Even the drab Sabbath of Wales and Scotland was under some threat, with pressure for opening cinemas in Wales and golf-courses in Scotland."[92]

Status of women[]

The occupation housewife[]

The 1950s was a bleak period for feminism. In the aftermath of World War II, a new emphasis was placed on traditional marriage and the nuclear family as a foundation of the new welfare state.[93] Women were expected to raise children and maintain the home while their husbands worked. The result was the popularization of the term 'occupation housewife', which emphasized a woman finding full-time work inside the home through childcare, cooking, cleaning and shopping.[94]

In 1951, the proportion of adult women who were (or had been) married was 75%; more specifically, 84.8% of women between the ages of 45 and 49 were married.[95] At that time: "marriage was more popular than ever before."[96] In 1953, a popular book of advice for women states: "A happy marriage may be seen, not as a holy state or something to which a few may luckily attain, but rather as the best course, the simplest, and the easiest way of life for us all".[97] Age at first marriage had also fallen consistently. By the end of the 1960s, both men and women were marrying at the lowest average age recorded for the past century at 27.2 and 24.7 years respectively.[98]

While at the end of the war, childcare facilities were closed and assistance for working women became limited, the social reforms implemented by the new welfare state included family allowances meant to subsidise families, that is, to support women in their "capacity as wife and mother".[99] Sue Bruley argues that "the progressive vision of the New Britain of 1945 was flawed by a fundamentally conservative view of women".[100]

Women's commitment to traditional marriage was echoed by the popular media: films, radio, books and popular women's magazines. In the 1950s, women's magazines had considerable influence on forming opinion in all walks of life, including the attitude to women's employment. A book published in 1950 called The Practical Home Handywoman was a guide for the 'occupational housewife' on topics including sewing, cooking, and basic carpentry.[101]

Daytime television also served to reinforce gender roles. As men were frequently at work during the day, programmes were primarily aimed at women. Marguerite Patten, a cooking show host during this 50s and 60s, became a household name. Her shows discussed ideal recipes for women to use during a time when rationing was still very much in place by incorporating easily accessible ingredients.[102]

Education also played a major role in the indoctrination of young girls into traditional gender roles. With greater funding and focus on public education, more and more British girls were being enrolled beyond primary school. However, the government took advantage of this for furthering a national agenda focused on returning to a pre-war family home by "[embedding] gendered curricula in secondary modern education".[103] Distinctions became particularly evident during 'domestic science lessons', which aimed to introduce girls to the kinds of domestic education they would have previously received at home.[104] Classes such as cooking, sewing, and family budgeting were common. Many of these classes lasted well into the late twentieth-century, only being gradually phased out as an emphasis on equal education for all children became the norm.[105]

Shifting attitudes[]

At the same time, women were increasingly interested in pursuing careers outside of the home, and this was certainly reflected in the politics of housewives' associations. Initially these organizations were formed to pressure local and national governments to pass policies that would protect mothers, through superior suburban infrastructure and more affordable homegoods.[103] However, by the end of the century their goals had shifted significantly to be more in line with demands made by working women, although their policy stances varied by organisation. The National Federation of Women's Institutes (WI) positioned themselves more conservatively, opting for 'married women' shift patterns that would have women work only during the school day and have more flexibility with time off should their child be sick.[103] By contrast, the National Council of Women (NCW) accepted research that childcare facilities did not have negative impacts on the wellbeing of children, and thus advocated for their expansion.[103]

1950s Britain moved to equal pay for teachers (1952) and for men and women in the civil service (1954), thanks to activists like Edith Summerskill.[106] Barbara Caine argues: "Ironically here, as with the vote, success was sometimes the worst enemy of organised feminism, as the achievement of each goal brought to an end the campaign which had been organised around it, leaving nothing in its place."[107]

Feminist writers of the early postwar period, such as Alva Myrdal and Viola Klein, started to allow for the possibility that women should be able to combine home duties with outside employment. Feminism was strongly connected to social responsibility and involved the well-being of society as a whole. This often came at the cost of the liberation and personal fulfillment of self-declared feminists. Even those women who regarded themselves as feminists strongly endorsed prevailing ideas about the primacy of children's needs, as advocated, for example, by John Bowlby the head of the Children's Department at the Tavistock Clinic and by Donald Winnicott.[108]

Career novels were a child and young adult genre that became very popular during this period.[109] These novels had a strong emphasis on working women with drive and ambition for their careers. Of course, realism was important, and many of the novels' heroines still married and found love, but these relationships were always represented as equal partnerships without professional sacrifice on the part of the main character.[109] However, it is important to note that the success of the career novel genre in UK was not as successful as its American counterpart, and some of the themes could be quite subtle.[109]

Equal pay entered the agenda at the 1959 general election, when the Labour Party's Manifesto proposed a charter of rights including: "the right to equal pay for equal work". Polls in 1968-9 showed public opinion moving in favour of equal pay for equal work; nearly three-quarters of those polled favoured the principle. The Equal Pay Act 1970 was passed by a Labour government with support from the Conservatives; it took effect in 1975. Women's wages for like work rose sharply from 64% in 1970 to 74% by 1980, then stalled because of high unemployment, and public-sector cuts that hit women working part-time.[110][111]

Sexuality in 1960s and 1970s[]

In the 1960s, the generations divided sharply regarding sexual freedoms demanded by youth that disrupted long-held norms such as no sex before marriage, and no adultery.[112]

Sexual morals changed rapidly. One notable event was the publication of D. H. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover by Penguin Books in 1960. Although first printed in 1928, the release in 1960 of an inexpensive paperback prompted a court case. The prosecutor's question, "Would you want your wife or servants to read this book?" highlighted how far society had changed, and how little some people had noticed. The book was seen as one of the first events in a general relaxation of sexual attitudes. The national media, based in London with its more permissive social norms, led in explaining and exploring the new permissiveness.[113]

Other elements of the sexual revolution included the development of the contraceptive pill, Mary Quant's miniskirt and the partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality in 1967. The incidence of divorce and abortion rose along with a resurgence of the women's liberation movement, whose campaigning helped secure the Equal Pay Act 1970 and the Sex Discrimination Act 1975.

Irish Catholics, traditionally the most puritanical of the ethno-religious groups, eased up a little, especially as the membership disregarded the bishops' teaching that contraception was sinful.[114]

The feminist movement drew inspiration primarily from the United States, and from the experience of left-wing British women experiencing discrimination by male activists. Efforts to form a national movement in the mid-1970s foundered on a bitter split between the (predominantly heterosexual) socialists, and the (predominantly lesbian) radicals. The most visible spokesperson was Germaine Greer, whose The Female Eunuch (1970) called on women to rebel against marriage and instead live in heterosexual communes. Paul Addison concludes, "in popular culture, feminism was generally treated as a bit of a joke."[115]

Teenagers[]

"Teenager" is an American word that first appeared in the British social scene in the late 1930s. National attention focused on them from the 1950s onwards.[116][117][118] Improved nutrition across the entire population was causing the age of menarche to fall on average by three or four months every decade, for well over a century. Young people aged between 12–20 were physically much more mature than before. They were better-educated, and their parents had more money.[119] National Service—the conscription of young men age 17–21 for compulsory military service-- was introduced in 1948; when it was abolished in 1960, the young men who would have reached conscription age had eighteen more months of freedom. The widespread use of washing machines, vacuum cleaners, kitchen appliances and prepared foods meant that teenage girls were no longer needed for so many household chores.[120]

The middle and upper-class populations were mostly still enrolled in school, so that much of the teenage phenomena of the postwar years was a product of the working-class. There are two dimensions of special importance, first the economics of teenage consumerism, and secondly; a middle-class moral panic about the decline in British morality. Looking just at the population of unmarried young people between 15–25 years of age, there were 5,000,000 of them in 1960, and they controlled about 10% of all personal income in Britain. They had blue-collar jobs that paid fairly well after the austerity years had ended. They typically lived at home, and did not spend their allowances and wages on housing, groceries, taxes, appliances, furniture or savings for the future. Instead, came the immediate need to urgently keep up with the standards of their peers; the present moment mattered, not the next again year. New stylish clothes as worn by the trend-setters were promptly copied. The weekend dances and musical performances were very well attended. One estimate in 1959 calculated the teenagers spent 20% of their money on clothes, cosmetics and shoes; 17% on drink and cigarettes; 15% on sweets, snacks and soft drinks; the rest, almost half, went to many forms of pop entertainment, from cinemas and dance halls to sports, magazines and records. Spending was a device that gave a person is sense of belonging to the group.[121]

Moral panics broke out in time of dramatic social change. Bouts of them appeared often in the Sexual Revolution and other events that widely changed social norms.[122][123] Teenager troubles first came to public attention during the war years, when there was a surge of juvenile delinquency.[124] By the 1950s, there was widespread concern about bellicose American comic books that adolescents liked to read. Censorship was imposed on these books in 1955.[125][126] By that point, the British media presented the teenagers in terms of generational rebellion, portraying them as rebellious and impulsive.[127] Subcultures such as skinheads and Teddy Boys appeared very ominous to the older generationd.[128] The moral panic among politicians and the older generation was typically belied by the growth in intergenerational co-operation between parents and children. Many working-class parents, enjoying newfound economic prosperity, eagerly took the opportunity to encourage their teens to enjoy more adventurous lives.[129] Schools were portrayed as dangerous blackboard jungles under the control of rowdy kids.[130]

Starting in the late 1960s, the counterculture movement spread from the United States like a wildfire.[131] Bill Osgerby argues that:

the counterculture's various strands developed from earlier artistic and political movements. On both sides of the Atlantic the 1950s "Beat Generation" had fused existentialist philosophy with jazz, poetry, literature, Eastern mysticism and drugs – themes that were all sustained in the 1960s counterculture.[132]

The UK did not experience the intense social turmoil produced in the US by the Vietnam War and racial tensions. Nevertheless, British youth readily identified with their American counterparts' desire to cast off the older generation's social mores. Music was a powerful force. British groups and stars such as The Beatles, Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Pink Floyd and many others gained huge followings in the UK and around the world, leading young people to question convention in everything from clothing to the class system.[133][134]

The anti-war movement in Britain was fueled by the counterculture. It collaborated with American counterparts, moving from an emphasis on nuclear war with Russia, to support for insurgents in the Southeast Asian jungles.[135]

Educational reform[]

The Education Act 1944 was an answer to surging social and educational demands created by the war and the widespread demands for social reform that approached utopianism.[136] It was prepared by Conservative MP Rab Butler after wide consultation. The Act took effect in 1947 and created the modern split between primary education and secondary education at the age of eleven years, previously, state educated children had often attended the same school from enrolment at about five years old until leaving school in their early teens. The newly-elected Labour government adopted the Tripartite System, consisting of grammar schools, secondary modern schools and secondary technical schools, rejecting the comprehensive school proposals favoured by many in the Labour Party as more equalitarian.[137] Under the tripartite model, students who passed an exam were able to attend a prestigious grammar school. Those who did not pass the selection test attended secondary modern schools, or technical schools. The school leaving age was raised to fifteen years. The elite system of public schools was practically unchanged.[138] The new law was widely praised by the Conservatives because it honoured religion and social hierarchy, and by Labour because it opened new opportunities for the working-class, and also by the general public; because it ended the fees they previously had to pay.[139] The Education Act became a permanent part of the Post-war consensus supported by the three major political parties.[140][141]

While the new law formed a part of the widely accepted Post-war consensus agreed to in general by the major parties, one part generated controversy. Left-wing critics attacked grammar schools as being elitist because a student had to pass a test at the age of eleven in order to enrol. Opponents, mostly in the Conservative Party, argued that grammar schools allowed pupils to obtain a good education through merit rather than through family income. By 1964, one in ten students were in comprehensive schools that did not sort children at the age of eleven. Labour education minister Anthony Crosland (from 1965) crusaded to speed up the process.[142] When Margaret Thatcher was appointed as Minister for Education in 1970, one in three schools were comprehensives; The proportion doubled by 1974, despite her efforts to resist the trend against grammar schools. By 1979, over 90% of schools in the UK were comprehensives.[143]

Higher education[]

Higher education expanded dramatically. Provincial university colleges were upgraded at Nottingham, Southampton and Exeter. By 1957, 21 universities were in existence. Expansion came even faster in the 1960s, with new universities such as: Keele, East Anglia, Essex, Kent, Sussex and York — bringing the total to 46 in 1970. Specialisation allowed national centres of excellence to emerge in Medicine at Edinburgh, engineering at Manchester, Science at Imperial College London, and Agriculture at Reading. Oxford and Cambridge; however, remained intellectually, culturally and politically dominant. They attracted top students from across the Commonwealth, but lost many of their best researchers to the United States, where salaries and research facilities were much more generous. Into the 1960s, student bodies remained largely middle and upper-class in origins; the average enrollment was only 2,600 in 1962.

Media[]

For the BBC the central postwar mission was to block threats from American private broadcasting and to continue John Reith's mission of cultural uplift.[144] The BBC remained a powerful force, despite the arrival of Independent Television in 1955.[145] Newspaper barons had less political power after 1945. Stephen Koss explains that the decline was caused by structural shifts: the major Fleet Street papers became properties of large, diversified capital empires with more interest in profits than politics. The provincial press virtually collapsed, with only the Manchester Guardian playing a national role; in 1964 it relocated to London. Growing competition arose from non-political journalism and from other media such as the BBC; independent press lords emerged who were independent of the political parties.[146]

Sport[]

Spectator sports became increasingly fashionable in postwar Britain, as attendance soared across the board.[147] Despite the omnipresent austerity, the government were very proud to host the 1948 Olympics, even though Britain's athletes won only three gold medals compared to 38 for the Americans.[148] Budgets were tight and no new facilities were built. Athletes were given the same bonus rations as dockers and miners, 5,467 calories a day instead of the normal 2,600. Athletes were housed in existing accommodation. Male competitors stayed at nearby RAF and Army camps, while the women were housed in London dormitories.[149] Sporting competitions were minimal during the war years, but by 1948, 40 million a year were watching football matches, 300,000 per week went to motorcycle speedways and half a million watched greyhound races. Cinemas were jammed and dance halls were filled. The great cricket hero Denis Compton was ultimately dominant; the Daily Telegraph reported he:

made his run gaily and with a smile. His happy demeanour and his good looks completed a picture of the beau ideal of a sportsman. I doubt if any game at any period has thrown up anyone to match his popular appeal in the England of 1947–1949.[150]

Cinema[]

The United Kingdom has had a significant film industry for over a century.[151] While film output peaked in 1936, the "golden age" of British cinema occurred in the 1940s, during which the directors David Lean, Michael Powell, Emeric Pressburger, Carol Reed and Richard Attenborough produced their most highly acclaimed work. Many postwar British actors achieved international fame and critical success, including: Maggie Smith, Michael Caine, Sean Connery, Peter Sellers and Ben Kingsley.[152] A handful of the films with the largest-ever box office returns have been made in the United Kingdom, including the second and third highest-grossing film series (Harry Potter and James Bond).[153]

Immigration[]

After decades of low immigration, new arrivals became a significant factor after 1945. In the decades after the second world war immigration was greatest from the former British Empire especially Ireland, India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, the Caribbean, South Africa, Kenya and Hong Kong..[154]

The new immigrants generally entered tight-knit ethnic communities. For example, the new Irish arrivals became integrated within a working-class Irish Catholic environment that shaped their behaviour whilst maintaining a distinct ethnic identity in terms of religion, culture and Labour politics.[155]

Enoch Powell, a Conservative MP, broke from the broad consensus supporting immigration in April 1968 to warn of long-term violence, unrest and internal discord should immigration continued from non-White countries. His speech foresaw "Rivers of Blood" and predicted that White "native" English citizens would be unable to access social services and be overwhelmed by foreign cultures. While political, social and cultural elites were harshly critical of Powell and he was removed from the Shadow Cabinet, Powell developed substantial public support.[156]

Historiography[]

Post-war consensus[]

The post-war consensus is a historians' model of political agreement from 1945 to 1979, when newly elected Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher rejected and reversed it. .[60] The concept claims there was a widespread consensus that covered support for a coherent package of policies that were developed in the 1930s, promised during the Second World War, and enacted under Attlee. The policies dealt with a mixed economy, Keynesianism, and a broad welfare state.[157] In recent years the validity of the interpretation has been debated by historians.

The historians' model of the post-war consensus was most fully developed by Paul Addison.[citation needed][158] The basic argument is that in the 1930s Liberal Party intellectuals led by John Maynard Keynes and William Beveridge developed a series of plans that became especially attractive as the wartime government promised a much better post-war Britain and saw the need to engage every sector of society. The coalition government during the war, headed by Churchill and Attlee, signed off on a series of white papers that promised Britain a much improved welfare state after the war. The promises included the national health service, and expansion of education, housing, and a number of welfare programmes. It did not include the nationalisation of all industries, which was a Labour Party design. The Labour Party did not challenge the system of elite public schools—they became part of the consensus, as did comprehensive schools. Nor did Labour challenge the primacy of Oxford and Cambridge. However, the consensus did call for building many new universities to dramatically broaden educational base of society. Conservatives did not challenge the socialised medicine of the National Health Service; indeed, they boasted they could do better job of running it.[159] In foreign policy, the consensus called for an anti-Communist Cold War policy, decolonisation, close ties to NATO, the United States, and the Commonwealth, and slowly emerging ties to the European Community.[160]

The model states that from 1945 until the arrival of Thatcher in 1979, there was a broad multi-partisan national consensus on social and economic policy, especially regarding the welfare state, nationalised health services, educational reform, a mixed economy, government regulation, Keynesian macroeconomic policies, and full employment. Apart from the question of nationalisation of some industries, these policies were broadly accepted by the three major parties, as well as by industry, the financial community and the labour movement. Until the 1980s, historians generally agreed on the existence and importance of the consensus. Some historians such as Ralph Miliband expressed disappointment that the consensus was a modest or even conservative package that blocked a fully socialised society.[161] Historian Angus Calder complained bitterly that the post-war reforms were an inadequate reward for the wartime sacrifices, and a cynical betrayal of the people's hope for a more just post-war society.[162] In recent years, there has been a historiographical debate on whether such a consensus ever existed.[163]

See also[]

- Social history of England § Since 1945

- History of gambling in the United Kingdom

- The Spirit of '45, a 2013 documentary film

References[]

- ^ Oaten, Mark (2007). Coalition: The Politics and Personalities of Coalition Government from 1850. Petersfield: Harriman House. p. 157. ISBN 978-1905641284.

N/A

- ^ "History - World Wars: Why Churchill Lost in 1945". BBC. Archived from the original on 26 December 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Kynaston 2010, p. 75.

- ^ "BBC Bitesize – National 5 History – Social Impact of WWII in Britain – Revision 2". www.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 December 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Morgan 1985, Chapter 1.

- ^ Pelling, Henry (1980). "The 1945 general election reconsidered". Historical Journal. 23 (2): 399–414. doi:10.1017/s0018246x0002433x. JSTOR 2638675.

- ^ "Designing Britain learning module". vads.ac.uk. Brighton University Of. 8 August 2002. Archived from the original on 25 October 2016. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ "What's a little debt between friends?". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Kynaston 2010.

- ^ "BBC – History – British History in depth: Britain, the Commonwealth and the End of Empire". Archived from the original on 8 January 2020. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Vinen, Richard (28 August 2014). "National Service: Conscription in Britain, 1945–1963". The Times Higher Education. Archived from the original on 21 September 2018. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- ^ Grant Jr, Philip A. (1995). "President Harry S. Truman and the British Loan Act of 1946". Presidential Studies Quarterly. 25 (3): 489–96.

- ^ Das, Dilip (2004). The Economic Dimensions of Globalization. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 70. ISBN 978-1349514335.

N/A

- ^ Rhiannon Vickers, Manipulating Hegemony: State Power, Labour and the Marshall Plan in Britain (2000) pp 44–48, 112–30

- ^ Morgan 1985, pp. 269–77.

- ^ Ina Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Austerity in Britain: Rationing, Controls, and Consumption, 1939–1955 (2000)[page needed]

- ^ Robertson, Alex J. (July 1989). The Bleak Midwinter, 1947. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2347-7.[page needed]

- ^ Hughes, R. Gerald (2007). Britain, Germany and the Cold War: The Search for a European Détente 1949–1967. Taylor & Francis. p. 11.

- ^ Richard Farmer, "'A Temporarily Vanished Civilisation': Ice Cream, Confectionery and Wartime Cinema-Going", Historical Journal of Film, Radio & Television, (December 2011) 31#4 pp 479–497,

- ^ Hinton, James (1994). "Militant Housewives: The British Housewives' League and the Attlee Government". History Workshop (38): 128–156. JSTOR 4289322.

- ^ Zweiniger-Bargileowska, Ina (1994). "Rationing, austerity and the Conservative party recovery after 1945". Historical Journal. 37 (1): 173–197. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00014758. JSTOR 2640057.

- ^ Kynaston 2010, pp. 445–453.

- ^ "London 1948 Summer Olympics – results & video highlights". International Olympic Committee. 31 January 2017. Archived from the original on 10 October 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Penrose, Sefryn (2012). "London 1948: the sites and after-lives of the austerity Olympics". World Archaeology. 44 (2): 306–325. doi:10.1080/00438243.2012.669647.

- ^ Reeves, Rachel; McIvor, Martin (2014). "Clement Attlee and the foundations of the British welfare state". Renewal: A Journal of Labour Politics. 22 (3/4): 42+. Archived from the original on 15 December 2018. Retrieved 3 August 2016.

- ^ Barr, N. A. (1993). The Economics of the Welfare State. Stanford UP. p. 33.

- ^ "The NHS history (1948–1959) – NHS England". NHS Choices. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Tomlinson, Jim (20 June 2002). Democratic Socialism and Economic Policy: The Attlee Years, 1945–1951. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-89259-9.

- ^ Thompson, Noel (2006). Political Economy and the Labour Party: The Economics of Democratic Socialism, 1884–2005. Manchester: Manchester University Press. pp. NB. ISBN 978-0415328814.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "BBC NEWS | UK | UK settles WWII debts to allies". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "BBC – Standard Grade Bitesize History – Urban housing : Revision, Page 3". Archived from the original on 14 October 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Catherine Flinn, Rebuilding Britain's Blitzed Cities: Hopeful Dreams, Stark Realities (Bloomsbury Academic, 2019) online review Archived 2020-01-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History of UK Housing | Economics Help". www.economicshelp.org. Archived from the original on 24 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Castella, Tom de (13 January 2015). "Why can't the UK build 240,000 houses a year?". BBC News. Archived from the original on 25 December 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "The History of Council Housing". fet.uwe.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 9 November 2016. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ "When Britain demanded fair shares for all". The Independent. 27 July 1995. Archived from the original on 11 August 2018. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Wilson, Wendy (30 March 2017). A short history of rent control (Report). House of Commons Library. Archived from the original on 8 October 2019. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ Levine, B.N. (1983). "British New Town Planning: A Wave of the Future or a Ripple across the Atlantic". Journal of Legislation. 10: 246–264. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017 – via NDL Scholarship.

- ^ Burnett 1986.

- ^ Francis, Martin (1 January 1995). "Economics and EthicsThe Nature of Labour's Socialism, 1945–1951". Twentieth Century British History. 6 (2): 220–243. doi:10.1093/tcbh/6.2.220. ISSN 0955-2359.

- ^ "Proud of the NHS at 60". Labour Party. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 15 March 2010.

- ^ Sked & Cook 1979, p. 29.

- ^ Sked & Cook 1979, Chapters 2–4.

- ^ Jack C. Ellis; Betsy A. McLane (2005). A New History of Documentary Film. A&C Black. p. 203.

- ^ Sked & Cook 1979, pp. 31–34.

- ^ Hutchison Beer, Samuel (1966). British politics in the collectivist age. Knopf. pp. 188–216.

- ^ Medlicott, William Norton (1967). Contemporary England: 1914–1964. D. McKay Company.

- ^ Kynaston 2010, p. 284.

- ^ Foot, Michael (6 October 2011). Aneurin Bevan: A Biography: Volume 2: 1945–1960. Faber & Faber. pp. 280–346. ISBN 978-0-571-28085-8.

- ^ Hogan, Michael J. (1987). The Marshall Plan: America, Britain and the Reconstruction of Western Europe, 1947–1952. Cambridge UP. pp. 143–45.

- ^ Pugh, Martin (26 January 2017). State and Society: A Social and Political History of Britain since 1870. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. Chapter 16. ISBN 978-1-4742-4347-6.

- ^ Kynaston 2010, Chapter 4.

- ^ Williamson, James (2008). "British Socialism and the Marshall Plan". History Today. 59 (2): 53–59.

- ^ Baylis, John (1982). "Britain and the Dunkirk Treaty: The Origins of NATO". Journal of Strategic Studies. 5 (2): 236–247. doi:10.1080/01402398208437111.

- ^ Baylis, John (1984). "Britain, the Brussels Pact and the continental commitment". International Affairs. 60 (4): 615–29. doi:10.2307/2620045. JSTOR 2620045.

- ^ Brendon, Piers (28 October 2008). The Decline and Fall of the British Empire, 1781–1997. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. Chapter 13–16. ISBN 978-0-307-27028-3.

- ^ Karp, Regina Cowen, ed. (1991). Security With Nuclear Weapons: Different Perspectives on National Security. Oxford U.P. pp. 145–47.

- ^ Zweiniger-Bargileowska, Ina (1994). "Rationing, austerity and the Conservative party recovery after 1945". Historical Journal. 37 (1): 173–97. doi:10.1017/S0018246X00014758.

- ^ Morgan 1992, p. 110.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Toye, Richard (2013). "From 'Consensus' to 'Common Ground': The Rhetoric of the Postwar Settlement and its Collapse". Journal of Contemporary History. 48 (1): 3–23. doi:10.1177/0022009412461816.

- ^ Morgan 1992, p. 114.

- ^ "1957: Britons 'have never had it so good'". BBC. 20 July 1957. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ^ Sloman, John; Garratt, Dean; Alison Wride (6 January 2015). Economics. Pearson Education Limited. p. 811. ISBN 978-1-292-06484-0.

- ^ Easton, Mark (2 May 2006). "Britain's happiness in decline". BBC. Archived from the original on 16 February 2009. Retrieved 12 March 2009.

- ^ Healey, Nigel, ed. (26 September 2002). Britain's Economic Miracle: Myth Or Reality?. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-89226-6.

- ^ Black, Lawrence; Pemberton, Hugh (28 July 2017). An Affluent Society?: Britain's Post-War 'Golden Age' Revisited. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-95917-9.

- ^ Kynaston 2009.

- ^ Gurney, Peter (2005). "The Battle of the Consumer in Postwar Britain". Journal of Modern History. 77 (4): 956–987. doi:10.1086/499831. JSTOR 10.1086/499831.

- ^ Van Vliet, Willem (1987). Housing Markets and Policies Under Fiscal Austerity. Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-25409-3.

- ^ Addison & Jones 2008.

- ^ Hollow, Matthew (2011). 'The Age of Affluence': Council Estates and Consumer Society. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ^ Sandbrook, Dominic (5 February 2015). Never Had It So Good: A History of Britain from Suez to the Beatles. Little, Brown Book Group. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-349-14127-5.

- ^ Hill, Charles Peter (1985). British Economic and Social History, 1700–1982. E. Arnold. ISBN 978-0-7131-7382-6.

- ^ Unstead, R. J. (1967). A Century of Change, 1837-today. Betterway. p. 224.

- ^ Pugh, Martin (2011). Speak for Britain!: A New History of the Labour Party. Vintage Books. pp. 315–. ISBN 978-0-09-952078-8.

- ^ Burnett 1986, p. 302.

- ^ Lapping, Brian (1970). The Labour Government, 1964–70. Penguin Books.

- ^ MacDowall, David (2000). Britain in Close-up: An In-depth Study of Contemporary Britain. Longman.

- ^ Anthony Sampson, The Essential Anatomy of Britain: Democracy in Crisis (1993) p 64

- ^ Harrison 2011, p. 305.

- ^ Harrison 2011, p. 305-6.

- ^ Turner, Alwyn W. (19 March 2009). Crisis? What Crisis?: Britain in the 1970s. Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-851-6.

- ^ Beckett, Andy (7 May 2009). When the Lights Went Out: Britain in the Seventies. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-25226-8.

- ^ Sked & Cook 1979, p. 324.

- ^ Bending, Richard; Eden, Richard (1984). UK Energy: Structure, Prospects and Policies. CUP Archive. ISBN 978-0-521-26708-3.

- ^ Hennessy, Peter (2007). Having it So Good: Britain in the Fifties. Penguin. p. 45.

- ^ Mulholland, M. (7 April 2000). Northern Ireland at the Crossroads: Ulster Unionism in the O'Neill Years, 1960–69. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-0-333-97786-6.

- ^ Dixon, Paul (26 September 2008). Northern Ireland: The Politics of War and Peace. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-05424-1.

- ^ Farrington, C. (28 February 2006). Ulster Unionism and the Peace Process in Northern Ireland. Springer. ISBN 978-0-230-80072-4.

- ^ Forster, Peter G. (1972). "Secularization in the English Context : Some Conceptual and Empirical Problems". Sociological Review. 20 (2): 153–68. doi:10.1111/j.1467-954x.1972.tb00206.x.

- ^ Hennessy 2006.

- ^ Morgan 1985, p. 299.

- ^ Pugh, Martin (1990). "Domesticity and the Decline of Feminism 1930–1950". In Smith, Harold L. (ed.). British feminism in the twentieth century. Elgar. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-85278-096-8..

- ^ Simonton, Deborah (2011). Women in European Culture and Society: Gender, Skill, and Identity from 1700. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge. pp. 321–323. ISBN 978-0-415-21308-0.

- ^ Lewis, Jane (1984). Women in England 1870–1950: Sexual Divisions and Social Change. Wheatsheaf Books. ISBN 978-0-7108-0186-9.

- ^ Sue Bruley, Women in Britain since 1900 (1999) p 131

- ^ Phyllis Whiteman, Speaking as a Woman (1953) p 67

- ^ "Marriages in England and Wales". www.ons.gov.uk. Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 19 April 2020. Retrieved 7 August 2020.

- ^ Martin Pugh, "Domesticity and the Decline of Feminism 1930–1950". p 158"

- ^ Bruley, Women in Britain since 1900 p 118

- ^ The Practical Home Handywoman: A Book of Basic Principles for the Self-Reliant Woman Dealing with All the Problems of Home-Making and Housekeeping. London: Odhams Press. 1950. p. 233.

- ^ Gillis, Stacy; Hollows, Joanne (7 September 2008). Feminism, Domesticity and Popular Culture. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-89426-9. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Beaumont, Caitríona (2 January 2017). "What Do Women Want? Housewives' Associations, Activism and Changing Representations of Women in the 1950s". Women's History Review. 26 (1): 147–162. doi:10.1080/09612025.2015.1123029. ISSN 0961-2025. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Spencer, Stephanie (July 2004). "Reflections on the 'site of struggle': girls' experience of secondary education in the late 1950s". History of Education. 33 (4): 437–449. doi:10.1080/0046760042000221817. ISSN 0046-760X. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Noddings, Nel. Education and democracy in the 21st century. New York. ISBN 978-0-8077-5396-5. OCLC 819105053. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Martin Pugh, Women and the women's movement in Britain, 1914–1999, (2000) p 284

- ^ Barbara Caine, English Feminism 1780–1980 (1997) p. 223

- ^ Finch and Summerfield (1991) p 11

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Spencer, Stephanie (July 2000). "Women's dilemmas in postwar Britain: career stories for adolescent girls in the 1950s". History of Education. 29 (4): 329–342. doi:10.1080/00467600050044680. ISSN 0046-760X. Archived from the original on 20 August 2020. Retrieved 8 August 2020.

- ^ Harrison 2009, p. 233.

- ^ Conley, Hazel (2014). "Trade unions, equal pay and the law in the UK" (PDF). Economic and Industrial Democracy. 35 (2): 309–323. doi:10.1177/0143831x13480410. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 May 2018. Retrieved 24 October 2018.

- ^ Andrew August, "Gender and 1960s Youth Culture: The Rolling Stones and the New Woman", Contemporary British History, (2009) 23#1 pp 79–100,

- ^ Frank Mort, Capital affairs: London and the making of the permissive society (Yale UP, 2010) online review Archived 2017-01-18 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ David Geiringer, "Catholic Understandings of Female Sexuality in 1960s Britain". Twentieth Century British History (2016) doi: 10.1093/tcbh/hww051

- ^ Paul Addison, No turning back: the peacetime revolutions of post-war Britain (2010). pp 218–19, 342–43

- ^ Melanie Tebbutt, Making Youth: A History of Youth in Modern Britain (2016).[page needed]

- ^ David Fowler, Youth culture in modern Britain, c. 1920-c. 1970: from ivory tower to global movement-a new history (2008).[page needed]

- ^ Bill Osgerby, Youth in Britain since 1945 (1998).[page needed]

- ^ Brian Harrison, Seeking a Role: The United Kingdom 1951 – 1970 (2009) pp 260–63,

- ^ Dominic Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good: A history of Britain from Suez to the Beatles (2005) pp 429–32.

- ^ Sandbrook, 435–36, citing Mark Abrams, Teenage Consumer Spending in 1959 (1961) pp 4–5.

- ^ Philip Jenkins, Intimate Enemies: Moral Panics in Contemporary Great Britain (1992).[page needed]

- ^ Eileen Yeo, "'The Boy is the Father of the Man': Moral Panic Over Working-Class Youth, 1850 to The Present". Labour History Review 69#2 (2004): 185–199.

- ^ David F. Smith, "Delinquency and welfare in London: 1939–1949". The London Journal 38#1 (2013): 67–87.

- ^ Sandbrook, 409–11.

- ^ Martin Barker, A Haunt of Fears, the Strange History of British Horror Comics Campaign (1984)

- ^ Sandbrook, 442–48.[incomplete short citation]

- ^ Mike Brake, "The skinheads: An English working class subculture". Youth & Society 6.2 (1974): 179–200.

- ^ Selina Todd, and Hilary Young. "Baby-Boomers to 'Beanstalkers' Making the Modern Teenager in Post-War Britain". Cultural and Social History 9#3 (2012): 451–467.

- ^ Tisdall, Laura (2015). "Inside the 'blackboard jungle' male teachers and male pupils at English secondary modern schools in fact and fiction, 1950 to 1959". Cultural and Social History. 12 (4): 489–507. doi:10.1080/14780038.2015.1088265.

- ^ Nelson, Elizabeth (25 September 1989). British Counter-Culture 1966–73: A Study Of The Underground Press. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-20217-1.[page needed]

- ^ Addison & Jones 2008, p. 132.

- ^ Stark, Steven D. (13 October 2009). Meet the Beatles: A Cultural History of the Band That Shook Youth, Gender, and the World. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-184252-8.

- ^ Faulk, Barry J. (23 May 2016). British Rock Modernism, 1967-1977: The Story of Music Hall in Rock. Routledge. pp. 5–. ISBN 978-1-317-17152-2.[page needed]

- ^ Sylvia A. Ellis, "Promoting solidarity at home and abroad: the goals and tactics of the anti-Vietnam War movement in Britain". European Review of History: Revue européenne d'histoire 21.4 (2014): 557–576.

- ^ Fry, G. (2001). The Politics of Crisis: An Interpretation of British Politics, 1931–1945. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 187–89.

- ^ Francis, Martin (1995). "A socialist policy for education?: Labour and the secondary school, 1945‐51". History of Education. 24 (4): 319–335. doi:10.1080/0046760950240404.

- ^ Anthony Howard, RAB: The Life of R. A. Butler (1987). pp 118–22

- ^ Paul Addison, The road to 1945: British politics and the Second World War (1975). pp 237–38.

- ^ Jeffereys, Kevin (1984). "R. A. Butler, the Board of Education and the 1944 Education Act". History. 69 (227): 415–431. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229x.1984.tb01429.x.

- ^ Simon, Brian (1986). "The 1944 Education Act: A Conservative Measure?". History of Education. 15 (1): 31–43. doi:10.1080/0046760860150104.

- ^ Dennis Dean, "Circular 10/65 Revisited: The Labour Government and the 'Comprehensive Revolution' in 1964‐1965". Paedagogica historica 34#1 (1998): 63–91.

- ^ Reitan, Earl Aaron (2003). The Thatcher Revolution: Margaret Thatcher, John Major, Tony Blair, and the Transformation of Modern Britain, 1979–2001. p. 14.

- ^ Simon Potter, Broadcasting Empire: The BBC and the British World, 1922–1970 (2012) ch 5–7

- ^ Garnham, Nicholas (1994). "The broadcasting market and the future of the BBC". Political Quarterly. 65 (1): 11–19. doi:10.1111/j.1467-923x.1994.tb00386.x.

- ^ Stephen Koss, The Rise and Fall of the Political Press in Britain. Vol. II, The Twentieth Century (1981)[page needed]

- ^ With the exception of Greyhound racing Harrison 2011, p. 386

- ^ Peter J. Beck, "The British government and the Olympic movement: the 1948 London Olympics". International Journal of the History of Sport 25#5 (2008): 615–647.

- ^ Hampton, Janie (1 January 2012). The Austerity Olympics: When the Games Came to London in 1948. Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-78131-001-4.[page needed]

- ^ Hennessy 2006, pp. 306, 316.

- ^ Curran, James; Porter, Vincent (1983). British cinema history. Weidenfeld and Nicolson.[page needed]

- ^ Babington, Bruce (2001). British Stars and Stardom: From Alma Taylor to Sean Connery. Manchester University Press. pp. 6–18. ISBN 978-0-7190-5841-7.

- ^ "Harry Potter becomes highest-grossing film franchise". The Guardian. London. 11 September 2007. Archived from the original on 18 February 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2010.

- ^ Hansen, Randall (2000). Citizenship and Immigration in Postwar Britain. Oxford University Press.[page needed]

- ^ Henrietta Ewart, "'Coventry Irish': Community, Class, Culture and Narrative in the Formation of a Migrant Identity, 1940–1970". Midland History (2013) pp 225–244.

- ^ Amy Whipple, "Revisiting the 'Rivers of Blood' Controversy: Letters to Enoch Powell". Journal of British Studies 48#3 (2009): 717–735.

- ^ Kavanagh, Dennis (1992). "The Postwar Consensus". Twentieth Century British History. 3 (2): 175–190. doi:10.1093/tcbh/3.2.175.

- ^ Addison, Paul (31 May 2011). The Road To 1945: British Politics and the Second World War Revised Edition. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4464-2421-6.

- ^ Klein, Rudolf (1985). "Why Britain's conservatives support a socialist health care system". Health Affairs. 4 (1): 41–58. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.4.1.41. PMID 3997046.[page needed]

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. (1969). Conflict and Consensus in Labour's Foreign Policy, 1914–1965. Stanford University Press. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-0-8047-0686-5.

- ^ Miliband, Ralph (1972). Parliamentary socialism: a study in the politics of labour. Merlin Press.[page needed]

- ^ Calder, Angus (31 July 2012). The People's War: Britain 1939–1945. Random House. ISBN 978-1-4481-0310-2.[page needed]

- ^ Ritschel, Daniel (January 2003). "Consensus in the Postwar Period After 1945". In Loades, D. M. (ed.). Reader's Guide to British History. 1. Taylor & Francis. pp. 296–297. ISBN 978-1-57958-242-5.

Further reading[]

- Addison, Paul; Jones, Harriet (2008). A Companion to Contemporary Britain, 1939–2000. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4051-4140-6.

- Addison, Paul (2010). No Turning Back: The Peacetime Revolutions of Post-War Britain. Oxford UP. ISBN 978-0-19-102984-4. excerpt and text search

- Black, Jeremy (2004). Britain Since the Seventies: Politics and Society in the Consumer Age. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-201-0. excerpt and text search

- Black, Lawrence; Pemberton, Hugh, eds. (2017). An Affluent Society?: Britain's Post-War 'Golden Age' Revisited. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-95917-9. online review