Science and technology in the United Kingdom

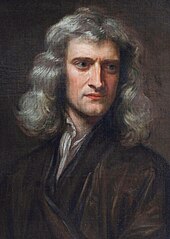

Science and technology in the United Kingdom has a long history, producing many important figures and developments in the field. Major theorists from the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland include Isaac Newton whose laws of motion and illumination of gravity have been seen as a keystone of modern science and Charles Darwin whose theory of evolution by natural selection was fundamental to the development of modern biology. Major scientific discoveries include hydrogen by Henry Cavendish, penicillin by Alexander Fleming, and the structure of DNA, by Francis Crick and others. Major engineering projects and applications pursued by people from the United Kingdom include the steam locomotive developed by Richard Trevithick and Andrew Vivian, the jet engine by Frank Whittle and the World Wide Web by Tim Berners-Lee. The United Kingdom continues to play a major role in the development of science and technology and major technological sectors include the aerospace, motor and pharmaceutical industries.

Important advances made by British people[]

England and Scotland were leading centres of the Scientific Revolution from the 17th century[1] and the United Kingdom led the Industrial Revolution from the 18th century,[2] and has continued to produce scientists and engineers credited with important advances.[3] Some of the major theories, discoveries and applications advanced by people from the United Kingdom are given below.

- The development of empiricism and its role in scientific method, by Francis Bacon (1561–1626).[4]

- The laws of motion and illumination of gravity, by physicist, mathematician, astronomer, natural philosopher, alchemist and theologian, Sir Isaac Newton (1643–1727).[5]

- The discovery of hydrogen, by Henry Cavendish (1731–1810).[6]

- The steam locomotive, by Richard Trevithick (1771–1833) and Andrew Vivian (1759–1842).[7]

- An early electric motor, by Michael Faraday (1771–1867), who largely made electricity viable for use in technology.[8]

- The theory of aerodynamics, by Sir George Cayley (1773–1857).[9]

- The first public steam railway, by George Stephenson (1781–1848).[10]

- The first commercial electrical telegraph, co-invented by Sir William Fothergill Cooke (1806–79) and Charles Wheatstone (1802–75).[11][12]

- First tunnel under a navigable river, first all iron ship and first railway to run express services, contributed to by Isambard Kingdom Brunel (1806–59).[13]

- Evolution by natural selection, by Charles Darwin (1809–82).[14]

- The invention of the incandescent light bulb, by Joseph Swan (1826–1914).[8]

- The unification of electromagnetism, by James Clerk Maxwell (1831–79).[15]

- The first practical telephone, patented by Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922).[note 2][16]

- The discovery of penicillin, by biologist and pharmacologist, Sir Alexander Fleming (1881–1955).[17]

- The world's first working television system, and colour television, by John Logie Baird (1888–1946).[18][19]

- The first meaningful synthesis of quantum mechanics with special relativity by Paul Dirac (1902–84) in the equation named after him, and his subsequent prediction of antimatter.[20]

- The invention of the jet engine, by Frank Whittle (1907–96).[21]

- The invention of the hovercraft, by Christopher Cockerell (1910–99).[22]

- The colossus computer, by Alan Turing (1912–54), an early digital computer (a code breaker in WWII made in Bletchley Park).[21]

- The structure of DNA, by Francis Crick (1916–2004) and others.[23]

- The theoretical breakthrough of the Higgs mechanism to explain electroweak symmetry breaking and why some particles have mass, by Peter Higgs (1929–).[24]

- Theories in cosmology, quantum gravity and black holes, by Stephen Hawking (1942–2018).[25]

- The invention of the World Wide Web, by Tim Berners-Lee (1955–).[26]

Technology-based industries[]

The United Kingdom plays a leading part in the aerospace industry, with companies including Rolls-Royce playing a leading role in the aero-engine market; BAE Systems acting as Britain's largest and the Pentagon's sixth largest defence supplier, and large companies including GKN acting as major suppliers to the Airbus project.[27] Two British-based companies, GlaxoSmithKline and AstraZeneca, ranked in the top five pharmaceutical companies in the world by sales in 2009[28] and UK companies have discovered and developed more leading medicines than any other country apart from the US.[29] The UK remains a leading centre of automotive design and production, particularly of engines, and has around 2,600 component manufacturers.[30] Investment by venture capital firms in UK technology companies was $9.7 billion from 2010 to 2015.[31]

More than 40 percent of all inventions are British too. Nanotechnology, space mining, superconductivity, smart materials, AI, supercomputers, geothermal and hydrogen energy and all potential application can serve a wide research base for the development of British research and the use of private funding. The UK will need to establish new industries, new trade links and new avenues of revenue as a result of diversifying its economy in the wake of Brexit and Covid.

Scientific research[]

Scientific research and development remains important in British universities, with many establishing science parks to facilitate production and co-operation with industry.[32] Between 2004 and 2012, the United Kingdom produced 6% of the world's scientific research papers and had an 8% share of scientific citations, the third- and second-highest in the world (after the United States' 9% and China's 7% respectively).[33][34] Scientific journals produced in the UK include Nature, the British Medical Journal and The Lancet.[35]

Britain was one of the largest recipients of research funding from the European Union. From 2007 to 2013, the UK received €8.8 billion out of a total of €107 billion expenditure on research, development and innovation in EU Member States, associated and third countries. At the time, this represented the fourth largest share in the EU.[36] The European Research Council granted 79 projects funding in the UK in 2017, more than any other EU country.[37][38] The United Kingdom was ranked 4th in the Global Innovation Index 2020, up from 5th in 2019.[39][40][41]

See also[]

- Government Office for Science

- Internet in the United Kingdom

- List of exports of the United Kingdom

- Manufacturing in the United Kingdom

- Telecommunications in the United Kingdom

Notes[]

- ^ Watt steam engine image: located in the lobby of into the Superior Technical School of Industrial Engineers of the UPM (Madrid)

- ^ Alexander Graham Bell, born and raised in Scotland, made a number of inventions as a British citizen, notably the telephone in 1876; he did not become an American citizen until 1882, and then spent the remaining years of his life predominately living in Canada at a summer residence.

References[]

- ^ J. Gascoin, "A reappraisal of the role of the universities in the Scientific Revolution", in David C. Lindberg and Robert S. Westman, eds, Reappraisals of the Scientific Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), ISBN 0-521-34804-8, p. 248.

- ^ "European Countries – United Kingdom". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- ^ E. E. Reynolds and N. H. Brasher, Britain in the Twentieth Century, 1900–1964 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1966), p. 336.

- ^ Urbach, Peter (1987). Francis Bacon's Philosophy of Science: An Account and a Reappraisal. La Salle, Ill.: Open Court Publishing Co. ISBN 9780912050447. p. 192.

- ^ E. A. Burtt, The Metaphysical Foundations of Modern Science (Mineola, NY: Courier Dover, 1924, rpt., 2003), ISBN 0-486-42551-7, p. 207.

- ^ Christa Jungnickel and Russell McCormmach, Cavendish (American Philosophical Society, 1996), ISBN 0-87169-220-1.

- ^ I. James, Remarkable Engineers: From Riquet to Shannon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), ISBN 0-521-73165-8, pp. 33–6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b B. Bova, The Story of Light (Sourcebooks, 1932, rpt., 2002), ISBN 1-4022-0009-9, p. 238.

- ^ Ackroyd, J.A.D. Sir George Cayley, the father of Aeronautics Notes Rec. R. Soc. Lond. 56 (2), 167–181 (2002). Retrieved: 29 May 2010.

- ^ Davies, Hunter (1975). George Stephenson. Weidenfeld and Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-76934-7.

- ^ Hubbard, Geoffrey (1965) Cooke and Wheatstone and the Invention of the Electric Telegraph, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London p. 78

- ^ The electric telegraph, forerunner of the internet, celebrates 170 years BT Group Connected Earth Online Museum - Retrieved March 2010

- ^ R. Tames, Isambard Kingdom Brunel (Osprey Publishing, 3rd edn., 2009), ISBN 0-7478-0758-2.

- ^ Jump up to: a b C. Hatt, Scientists and Their Discoveries (London: Evans Brothers, 2006), ISBN 0-237-53195-X, p. 46.

- ^ C. Hatt, Scientists and Their Discoveries (London: Evans Brothers, 2006), ISBN 0-237-53195-X, p. 30.

- ^ "Alexander Graham Bell (1847–1922)", Scottish Science Hall of Game, 159 (4035): 297, 1947, Bibcode:1947Natur.159Q.297., doi:10.1038/159297a0, S2CID 4072391, archived from the original on 21 June 2011.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 1945 Sir Alexander Fleming, Ernst B. Chain, Sir Howard Florey", Nobelprize.org, archived from the original on 21 June 2011.

- ^ "John Logie Baird (1888–1946)", BBC History, archived from the original on 21 June 2011.

- ^ The World's First High Definition Colour Television System McLean, p. 196.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Physics 1933". The Nobel Foundation. Retrieved 2007-11-24.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Jeffrey Cole, Ethnic Groups of Europe: An Encyclopedia (London: ABC-CLIO, 2011), ISBN 1-59884-302-8, p. 121.

- ^ "Sir Christopher Sydney Cockerell" Archived 2008-07-06 at the Wayback Machine, Hovercraft Museum, retrieved 24 June 2011.

- ^ C. Hatt, Scientists and Their Discoveries (London: Evans Brothers, 2006), ISBN 0-237-53195-X, p. 56.

- ^ Griffiths, Martin (20070501) physicsworld.com The Tale of the Blog's Boson Retrieved on 2008-05-27.

- ^ C. Hatt, Scientists and Their Discoveries (London: Evans Brothers, 2006), ISBN 0-237-53195-X, p. 16.

- ^ webfoundation.org/.../history-of-the-web

- ^ O’Connell, Dominic, "Britannia still rules the skies", The Sunday Times.

- ^ "IMS Health" (PDF), IMS Health, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2011.

- ^ "The Pharmaceutical sector in the UK", The National Archives, 8 August 2007, archived from the original on 7 August 2007.

- ^ "Automotive industry", Department of Business Innovation and Skills, archived from the original on 21 June 2011.

- ^ "UK tech firms smash venture capital funding record". London & Partners. 6 January 2016. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- ^ M. Castells, P. Hall, P. G. Hall, Technopoles of the World: the Making of Twenty-First-Century Industrial Complexes (London: Routledge, 1994), ISBN 0-415-10015-1, pp. 98–100.

- ^ Knowledge, networks and nations: scientific collaborations in the twenty-first century (PDF), Royal Society, 2011, ISBN 978-0-85403-890-9, archived from the original (PDF) on 22 June 2011.

- ^ MacLeod, Donald (March 21, 2006). "Britain Second in World Research Rankings". The Guardian. London. Retrieved May 14, 2006.

- ^ McCook, Alison (2006), "Is peer review broken?", The Scientist, 20 (2): 26, archived from the original on 21 June 2011.

- ^ "How much research funding does the UK get from the EU and how does this compare with other countries?". Royal Society. 23 November 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ^ "Boost for hopes of post-Brexit co-operation as EU awards Britain more research grants than anywhere else". The Telegraph. 6 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "ERC Starting Grants 2017" (PDF). European Research Council. 6 September 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2017.

- ^ "Release of the Global Innovation Index 2020: Who Will Finance Innovation?". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ "Global Innovation Index 2019". www.wipo.int. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- ^ "RTD - Item". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 2021-09-02.

- Science and technology in the United Kingdom