Sonny Bono

Sonny Bono | |

|---|---|

Bono in 1966 | |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from California's 44th district | |

| In office January 3, 1995 – January 5, 1998 | |

| Preceded by | Al McCandless |

| Succeeded by | Mary Bono |

| 16th Mayor of Palm Springs | |

| In office April 1988 – April 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Frank Bogert |

| Succeeded by | Lloyd Maryanov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Salvatore Phillip Bono February 16, 1935 Detroit, Michigan, U.S. |

| Died | January 5, 1998 (aged 62) Stateline, Nevada, U.S. |

| Cause of death | Skiing accident |

| Resting place | Desert Memorial Park, Cathedral City, California, U.S. |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Donna Rankin

(m. 1954; div. 1962)Cher

(m. 1964; div. 1975)Susie Coelho

(m. 1981; div. 1984) |

| Children | 4, including Chaz |

| Residence | Palm Springs, California, U.S. |

| Musical career | |

| Origin | Inglewood, California, U.S. |

| Genres | |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Years active | 1963–1995 |

| Associated acts | Cher Sonny & Cher |

Salvatore Phillip "Sonny" Bono (/ˈboʊnoʊ/; February 16, 1935 – January 5, 1998) was an American singer-songwriter, producer, actor, and politician who came to fame in partnership with his second wife Cher as the popular singing duo Sonny & Cher. He was mayor of Palm Springs, California, from 1988 to 1992, and the Republican congressman for California's 44th district, elected during the Republican Revolution and serving from 1995 until his death in 1998.

The United States Copyright Term Extension Act of 1998, which extended the term of copyright by 20 years, was named in honor of Bono when it was passed by Congress nine months after his death. Mary Bono (Sonny's last wife) had been one of the original sponsors of the legislation, commonly known as the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act.[1]

Early life[]

Bono was born in Detroit to Santo Bono (born in Montelepre, Palermo, Italy) and Zena "Jean" Bono (née DiMercurio).[2] His mother called him "Sono" as a term of endearment, which evolved over time into "Sonny".[3][4] Sonny was the youngest of three siblings; he had two sisters, Fran and Betty.[2] The family moved to Inglewood, California, when he was seven, and his parents divorced soon afterwards.[2] Bono decided early in life to become part of the music business, and began writing songs as a teenager.[5] "Koko Joe", a song he wrote at age 16, was recorded by Don and Dewey in 1958, and later covered by several other artists including The Righteous Brothers.[6] Bono attended Inglewood High School, but did not graduate, opting to drop out so he could begin to pursue a career as a songwriter and performer.[2][7] He worked at a variety of jobs while trying to break into the music business, including waiter, truck driver, construction laborer, and butcher's helper.[8]

Career[]

Entertainment career[]

Bono began his music career as a songwriter at Specialty Records, where his song "Things You Do to Me" was recorded by Sam Cooke, and went on to work for record producer Phil Spector in the early 1960s as a promotion man, percussionist and "gofer". One of his earliest songwriting efforts, "Needles and Pins" was co-written with Jack Nitzsche, another member of Spector's production team. Later in the same decade, he achieved commercial success with his wife Cher in the singing duo Sonny and Cher. Bono wrote, arranged and produced a number of hit records including the singles "I Got You Babe" and "The Beat Goes On", although Cher received more attention as a performer.[9] He played a major part in Cher's solo recording career, writing and producing singles including "Bang Bang" and "You Better Sit Down Kids".

Bono co-wrote "She Said Yeah",[citation needed] covered by The Rolling Stones on their 1965 LP December's Children. His lone hit single as a solo artist, "Laugh at Me", was released in 1965 and peaked at No. 10 on the Billboard Hot 100. In live concerts, Bono introduced the song by saying "I'd like to sing a medley of my hit". His only other single as a solo artist, "The Revolution Kind", reached No. 70 on the Billboard Hot 100 later that year. His solo album, Inner Views, was released in 1967.[10]

Sonny continued to work with Cher through the early and mid-1970s, starring in a popular television variety show, The Sonny and Cher Comedy Hour, which ran on CBS from 1971 to 1974. From 1976 to 1977, the duo, since divorced, returned to perform together on The Sonny and Cher Show. Their last appearance together was on Late Night with David Letterman on November 13, 1987, on which they sang "I Got You Babe".[11][12]

"What we call a hook hits you, ... then you're almost not writing, lyrics come to you, a sort of magic takes over, and it's not like work at all."

-Sonny Bono on songwriting, 1967 Pop Chronicles interview.[9]

In 2011, Sonny Bono was inducted into the Michigan Rock and Roll Legends Hall of Fame.[13]

Film and television[]

Bono's acting career included bit parts as a guest performer in such television series as Fantasy Island, Charlie's Angels, The Love Boat, The Six Million Dollar Man and CHiPs. In the 1975 TV movie Murder on Flight 502, he played the role of rock star Jack Marshall. He appeared in the 1980 miniseries Top of the Hill. He played the role of mad bomber Joe Selucci in Airplane II: The Sequel (1982) and appeared in the horror film Troll (1986). He also portrayed racist entrepreneur Franklin von Tussle in the John Waters film Hairspray (1988). In Men in Black (1997), Bono is one of several oddball celebrities seen on a wall of video screens that monitor extraterrestrials living among us. He also appeared as the Mayor of Palm Springs (which he actually was at the time) in several episodes of P.S. I Luv U during the 1991–92 TV season, and on Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman (in season 1, episode 9, which aired November 21, 1993), in which he played Mayor Frank Berkowitz. He also made a minor appearance as himself in the comedy film First Kid (1996).

Bono guest-starred as himself on The Golden Girls episode "Mrs. George Devereaux" (originally broadcast November 17, 1990), in which he vied with Lyle Waggoner for Dorothy's (Bea Arthur) affection in a dream sequence. In Blanche's (Rue McClanahan) dream, her husband is still alive, and Bono uses his power as Mayor of Palm Springs to have Waggoner falsely arrested so he can have Dorothy to himself. Sophia (Estelle Getty) had been hoping for Sonny and Dorothy to get together and actively supported Sonny.

The picture of Bono was seen briefly in the Silly Songs segment, "Love My Lips", in the VeggieTales video Dave and the Giant Pickle (released in 1996) until it was removed in the 1998 re-issue after his death.

Political career[]

Bono entered politics after experiencing great frustration with local government bureaucracy in trying to open a restaurant in Palm Springs, California. Bono made a successful bid to become the new mayor of Palm Springs. He served four years, from 1988 to 1992.[14] He was instrumental in spearheading the creation of the Palm Springs International Film Festival, which is held each year in Bono's memory.

Bono ran for the Republican nomination for United States Senate in 1992, but the nomination went to the more conservative Bruce Herschensohn, and the election to the Democrat Barbara Boxer. Bono and Herschensohn became close friends after the campaign. Bono was elected to the United States House of Representatives in 1994 to represent California's 44th congressional district. He was one of twelve co-sponsors of a House bill extending copyright.[15] Although that bill was never voted on in the Senate, a similar Senate bill was passed after his death and named the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act in his memory. It is also known (derisively) as the Mickey Mouse Protection Act.[16]

He championed the restoration of the Salton Sea,[17] bringing the giant lake's plight to national attention. In 1998, then Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich made a public appearance and speech at the shore of the lake on Bono's behalf.

In their book Tell Newt to Shut Up, David Maraniss and Michael Weisskopf credit Bono with being the first person to recognize Gingrich's public relations problems in 1995. Drawing on his long experience as a celebrity and entertainment producer, Bono (according to Maraniss and Weisskopf) recognized that Gingrich's status had changed from politician to celebrity and that he was not making allowances for that change:

You're a celebrity now, ... The rules are different for celebrities. I know it. I've been there. I've been a celebrity. I used to be a bigger celebrity. But let me tell you, you're not being handled right. This is not political news coverage. This is celebrity status. You need handlers. You need to understand what you're doing. You need to understand the attitude of the media toward celebrities.

Bono remains the only member of Congress to have scored a number-one pop single on the US Billboard Hot 100 chart.[18]

Personal life[]

Marriages[]

Bono was married four times. He married his first wife, Donna Rankin, on November 3, 1954. Their daughter Christine ("Christy") was born on June 24, 1958. They divorced in 1962.

In 1964, Bono married singer and actress Cher. They had one child, Chaz Bono, born March 4, 1969, and divorced in 1975.[7]

Bono married actress-model Susie Coelho on New Year's Eve 1981;[19] they divorced in 1984.[20]

He wed Mary Whitaker in 1986 and they had two children, son Chesare Elan in 1988 and daughter Chianna Maria in 1991.[7]

Godparent[]

Bono was named a godparent of Anthony Kiedis, who became a musical artist with his band, Red Hot Chili Peppers. Sonny was a close friend of Kiedis's father, Blackie Dammett, and often took the boy on weekend trips.[21][22]

Salton Sea[]

Bono was a champion of the Salton Sea in southeastern California, where a park was named in his honor. The 2005 documentary film Plagues & Pleasures on the Salton Sea[23] (narrated by John Waters) features Bono and documented the lives of the inhabitants of Bombay Beach, Niland and Salton City, as well as the ecological issues associated with the Sea.

Religion[]

He became interested in Scientology and took Scientology courses partly because of the influence of Mimi Rogers, but stated that he was a Roman Catholic on all official documents, campaign materials and websites.[24] His wife Mary also took Scientology courses.[25][26] However, after his death, Mary Bono stated that "Sonny did try to break away [from the Church of Scientology] at one point, and they made it very difficult for him." The Church of Scientology said there was no estrangement from Bono.[27]

Death[]

| External video | |

|---|---|

Bono died on January 5, 1998, of injuries incurred when he hit a tree while skiing at Heavenly Mountain Resort in South Lake Tahoe, California.[28][29] After Bono's death, Mary Bono said that Sonny had been addicted to prescription drugs (mainly Vicodin and Valium) and that she believed her husband's drug use caused the accident. No drugs or alcohol were found in his body.[28]

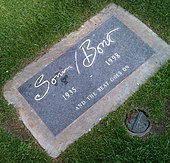

At Mary's request, Cher gave a eulogy at Sonny's funeral. He was buried at Desert Memorial Park in Cathedral City, California.[30][31] The epitaph on Bono's headstone reads AND THE BEAT GOES ON.[32]

Mary Bono was elected to fill the remainder of her husband's congressional term. She was elected in her own right seven subsequent times before being defeated in the election of 2012.[33]

Honors and tributes[]

Sonny Bono has been honored and memorialized with:

- A Golden Palm Star on the Palm Springs Walk of Stars: dedicated to him in 1996.[34]

- Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act: Extended copyright protections effective October 27, 1998.

- Sonny Bono Salton Sea National Wildlife Refuge: a nature reserve on the Salton Sea was renamed in Bono's honor in 1998.

- Sonny Bono Memorial Park, a small park in Washington, D.C., was named in his honor in 1998.

- Sonny Bono Memorial Interchange: an interchange on California State Route 60 at Nason Street in Moreno Valley, California, was named for Bono in September 2000.[35]

- Sony Bono Memorial Freeway: a 40-mile stretch of Interstate Highway 10 near Palm Springs was dedicated January 10, 2002.[36]

- Sonny Bono Concourse: a concourse at Palm Springs International Airport dedicated October 22, 2002.[37]

- Sonny Bono Memorial Fountain and Statue: Located in downtown Palm Springs, California, the statue was dedicated in November 2002.[38]

See also[]

- List of actor–politicians

- List of famous skiing deaths

- List of United States Congress members who died in office (1950–99)

Citations[]

- ^ "U.S. Copyright Office: Annual Report 2002: Litigation". Copyright.gov. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Larocque, Jason (2013). Cher: You Haven't Seen The Last of Me. Charlotte, NC: Baker & Taylor. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-300-88858-1.

- ^ "Sonny Bono Biography". Yahoo! Movies. Archived from the original on February 17, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Kephart, Robert (February 16, 2016). "Palm Springs Remembers Sonny Bono – February 16, 1935 – January 5, 1998". I Love Palm Springs!. Palm Springs, CA: Palm Springs Guru.

- ^ Morris, Chris; Holland, Bill (January 17, 1998). "Bono Recalled as Politician and Performer". Billboard. New York, NY. p. 16.

- ^ Hodenfield, Chris (May 24, 1973). "As Bare As You Dare With Sonny and Cher". Rolling Stone. New York, NY.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Yates, Nona (January 7, 1998). "Sonny Bono, a Chronology". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Bego, Mark (2001). Cher: If You Believe. Lanham, MD: Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-58979-135-0.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gilliland, John (1969). "Show 44 – Revolt of the Fat Angel: Some samples of the Los Angeles sound. [Part 4]" (audio). Pop Chronicles. University of North Texas Libraries. Track 1.

- ^ "Sonny Bono – Inner Views – from Rhino Handmade". Rhinohandmade.com. Retrieved February 10, 2015.

- ^ "Sonny & Cher Boost Ratings". The New Mexican. Santa Fe, New Mexico. November 29, 1987, p. 35, accessed through NewspaperARCHIVE.com on March 13, 2009.

- ^ "Sonny and Cher Reunited on David Letterman Show." Aiken Standard. Aiken, South Carolina. November 15, 1987. p. 3. accessed through NewspaperARCHIVE.com on March 13, 2009.

- ^ Johnson, Gary. "Michigan Rock and Roll Legends – Sonny Bono". www.michiganrockandrolllegends.com.

- ^ "Bono, Sonny – Biographical Information". Bioguide.congress.gov. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ "Bill Summary & Status – 105th Congress (1997–1998) – H.R.2589 – THOMAS (Library of Congress)". Thomas.loc.gov. March 26, 1998. Archived from the original on November 27, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ Lawrence Lessig, Copyright's First Amendment, 48 UCLA L. Rev. 1057, 1065 (2001)

- ^ "Salton Sea rescue to be named for Sonny Bono". CNN. January 16, 1998.

- ^ "Rewinding the Charts: Fifty Years Ago, Sonny & Cher 'Got' to No. 1". Billboard. Retrieved December 2, 2017.

- ^ "Singer-actor Sonny Bono". Reading Eagle. (Pennsylvania). UPI photo. January 2, 1982. p. 6.

- ^ "Bono Takes Third Trip To The Altar". The Tampa Tribune. January 2, 1982.

- ^ "Anthony Kiedis". Angelfire. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ "Kiedis' Bedroom Joy With Cher". Contactmusic.com. October 11, 2004. Retrieved April 25, 2012.

- ^ "Plagues & Pleasures on the Salton Sea". Saltonseadoc.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2010. Retrieved October 8, 2009.

- ^ Wright, Lawrence (November 5, 2013). Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood, and the prison of belief. New York City: Vintage. pp. 249–50. ISBN 978-0307745309.

- ^ Pareene, Alex (February 10, 2011). "The Cult of Scientology's friends in Washington". Salon. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ^ Bardach, Ann (August 1999). "Proud Mary Bono". George. Retrieved May 17, 2015.

- ^ Babington, Charles (July 15, 1999). "Bono Not Receptive to Scientologists". The Washington Post. p. A5. Retrieved September 24, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Claiborne, William (January 7, 1998). "Sonny Bono Is Killed in Ski Crash". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Sonny Bono Killed in Skiing Accident". CNN. January 6, 1998. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2016.

- ^ "Palm Springs Cemetery District "Interment Information"" (PDF).

- ^ Brooks, Patricia; Brooks, Jonathan (2006). "Chapter 8: East L.A. and the Desert". Laid to Rest in California: a guide to the cemeteries and grave sites of the rich and famous. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot Press. pp. 239–40. ISBN 978-0762741014.

- ^ Pilato, Herbie J. (July 20, 2016). Dashing, Daring, and Debonair: TV's Top Male Icons from the 50s, 60s, and 70s. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781630760533 – via Google Books.

- ^ Lochhead, Carolyn (November 7, 2012). "Mary Bono Mack defeated in Palm Springs upset". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved November 7, 2012.

- ^ "Palm Springs Walk of Stars by date dedicated" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 13, 2012.

- ^ Leech, Marie (September 14, 2000). "Proposed Fountain Would Honor Sonny Bono". The Desert Sun.

- ^ Trone, Kimberly (January 11, 2002). "Freeway Signs Pay Tribute to Bono". The Desert Sun. p. B1.

- ^ "Airport Adds Sonny Bono Concourse". Billboard. AP. October 29, 2002. Retrieved June 18, 2019.

- ^ Guzman, Richard (November 17, 2001). "Palm Springs inaugurates Bono tribute". The Desert Sun.

Further reading[]

- Sonny Bono: And the Beat Goes On. New York: Pocket Books 1991. ISBN 0-671-69366-2

- Joel Whitburn's Top Pop Singles, 12th edition. Menomonee Falls, WI: Record Research, 2009. ISBN 978-0-89820-180-2.

- Bono vs. Bono: A Battle Royal , Bobby Soxers, 2013. ISBN 978-1492349976.

External links[]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sonny Bono. |

- Biography at the Biographical Directory of the United States Congress

- Sonny Bono at IMDb

- Sonny Bono at the TCM Movie Database

- Sonny Bono interviewed on the Pop Chronicles (1969)

- Sonny Bono: Pop Songs & Politics at the TCM Movie Database

- FBI Records: The Vault – Salvatore Phillip "Sonny" Bono at vault.fbi.gov

- S.505: Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act

- Appearances on C-SPAN

| show |

|---|

- Sonny Bono

- 1935 births

- 1998 deaths

- American actor-politicians

- American male film actors

- American male singer-songwriters

- American people of Italian descent

- American politicians of Italian descent

- Record producers from California

- American Scientologists

- American singer-songwriters

- American male television actors

- Burials at Desert Memorial Park

- California Republicans

- Mayors of Palm Springs, California

- Members of the United States House of Representatives from California

- Male actors from Detroit

- Skiing deaths

- Specialty Records artists

- Sports deaths in California

- Sonny & Cher

- 20th-century American male actors

- Musicians from Inglewood, California

- Male actors from Palm Springs, California

- Atco Records artists

- Republican Party members of the United States House of Representatives

- 20th-century American singers

- 20th-century American politicians

- The Wrecking Crew (music) members

- Catholics from California

- 20th-century male singers