Spanish Hill

| Spanish Hill | |

|---|---|

Spanish Hill from the south, as depicted in an 1881 lithograph | |

| |

| Location | Bradford County, Pennsylvania, USA |

| Coordinates | 41°59′45″N 76°32′58″W / 41.9959074°N 76.5493893°WCoordinates: 41°59′45″N 76°32′58″W / 41.9959074°N 76.5493893°W |

| Elevation | 978 feet (298 m) |

Spanish Hill is a hill located in the borough of South Waverly, Pennsylvania. Opinions regarding the origin of structures found on the site vary from embankments created by early farmers, to the remnants of a Native American village and battlements, due to the site's similarity to the description found in the account of Étienne Brûlé of a settlement called Carantouan. The area in the hill's vicinity was previously occupied by Susquehannock Native Americans. It was a common site for both amateur and professional archaeology, as well as relic hunting. The source of the name remains unknown, but various theories have been proposed as to its origin.

Geography[]

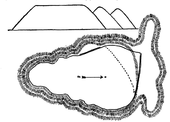

In 1795, François Alexandre Frédéric visited Spanish Hill while en route to Canada.[1] He described the hill as "a mountain in the shape of a sugar loaf, about 100 feet high, with level top, on which are remains of intrenchments. One perpendicular breastwork is still remaining, plainly indicating a parapet and ditch."[2] In 1833, another individual visiting the hill described "the remains of a wall which runs around the whole exactly on the brow, and within a deep ditch or intrenchment running round the whole summit."[2] In 1898, I.P. Shepard created a sketch of Spanish Hill, including the portions still visible at the time as well as those no longer extant.[3] Shepard enlisted the assistance of a longtime local resident, Charles Henry Shepard, who claimed to remember "fortifications as consisting of an embankment with a trench behind, giving a height of four or five feet on the inside."[3] In addition, an indent was discovered on the site which was pronounced to be a corn cache by Beauchamp.[4]

According to John S. Clark, a surveyor and historian active in the area until the early twentieth century, the topography and size of the site were appropriate to correspond with Brûlé's description of Carantouan;[2] Brûlé described a palisaded town, populated by approximately 800 warriors and 4,000 individuals in total.[5] He also described the dwellings and fortifications as being similar to those utilized by the Wyandot people.[5] Clark's conclusions were based in part on surveys he conducted at the site in 1878, when he observed what he believed were fortifications atop the hill.[1] Amateur archaeologist Ellsworth C. Cowles conducted an excavation at the base of the hill in 1932, uncovering what he described as "seventy five postholes extending east and west," as well as the "effigy of a huge animal."[6]

History[]

Originally created by receding glaciers,[2] Spanish Hill comprises approximately 10 acres (40,000 m2) of earth in a site that is part of the Sayre quadrangle.[7][8] Located at an elevation of 978 feet (298 m) above sea level,[8] it rises approximately 230 feet (70 m) over the nearby floodplain of the Chemung River.[7] The hill is located in South Waverly, Pennsylvania, in Bradford County,[7] just south of the state border with New York, inside of territory once occupied by the Susquehannock people. It has been acknowledged and studied by historians and archaeologists for over two hundred years.[7] The source of the name is unknown, but individuals traveling through the area between 1795 and 1804 described "Spanish Ramparts" as a feature of the hill,[2] and some of the earliest settlers to the region report that local Native Americans referred to the hill either as "Hispan" or "Espan."[9] In 1615, Étienne Brûlé was sent to the area by Samuel de Champlain to meet with Native American tribes in the hope of finding assistance to fight the Iroquois, against whom Champlain had allied with the Wyandot people.[10] During his voyage, Brûlé recorded a town called Carantouan (meaning "Big Tree," according to ethnologist William Martin Beauchamp),[11] which was subsequently included on a map published by de Champlain in 1632.[12] In the early nineteenth-century, a Native American man who lived in the area near Spanish Hill reportedly refused to ascend it, for fear of a deadly spirit that lived on top.[13] According to the man, the spirit spoke with a thunderous voice and "made holes through Indians' bodies."[13] Archaeologist Louise Welles Murray suggested that this could be a reference to cannon or musket fire.[13]

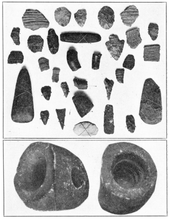

In the early twentieth century, archaeological and historical research was conducted regarding a potential connection between Carantouan and the structures described on the hill.[14] After surveying the area in spring and fall, archaeologist L.D. Shoemaker discovered evidence of Native American habitation, including shell heaps, corn and flint chips, along with various other implements.[15] In 1918, historian and archaeologist George P. Donehoo, after a survey of the site, determined that it was impossible for Spanish Hill to have been the site of the town described by Brûlé.[16] He cited the sharp incline, which would have made ascension difficult, as well as the lack of water and archaeological evidence on the hill as evidence against it having been the location of Carantouan.[16] Speculation that Spanish Hill was the site of the village was also countered by James Bennett Griffin, who found nothing of interest in the area following an archaeological survey in 1931.[17] However, historian Deb Twigg suggests that prior excavations conducted by early twentieth-century archaeologist Warren Moorehead, as well as years of heavy farming activity in the area may have contributed to the lack of artifacts found during the Griffin expedition.[17] As Twig wrote: “Until more information is known, it seems imprudent to eliminate Spanish Hill as a possible site related to the nation of Carantouan, as some researchers have done.”[18]

The site was a popular location, both for archaeological excavations and amateur collecting.[6] According to Twigg, Spanish Hill was "looted" by Moorehead, and his finds likely sold to collectors.[17] In addition, the area was heavily scoured by relic collectors approximately since the early nineteenth-century.[15]

On October 15, 1915, the Historical Society of Bradford County, Pennsylvania, dedicated a memorial on Spanish Hill in honor of the tricentennial of the arrival of Brûlé to the present-day border of Pennsylvania.[19] Later, in 1939, Section of Painting and Sculpture artist Musa McKim depicted the hill in a mural entitled "Spanish Hill and the Early Inhabitants of the Vicinity," for display in the United States Post Office branch of nearby Waverly, New York.[20] The hill was nearly demolished and used for highway fill in 1970, but the efforts were reportedly halted due to lobbying by local amateur archaeologist Ellsworth Cowles.[21]

References[]

- ^ a b Twigg 2005, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e Murray 1921, p. 289.

- ^ a b Murray 1908, p. 58.

- ^ Murray 1908, p. 59.

- ^ a b Parkman 1897, p. 235.

- ^ a b Lenik 2009, p. 114.

- ^ a b c d Lenik 2009, p. 113.

- ^ a b "Spanish Hill (Pennsylvania)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ^ Murray 1908, pp. 61–62.

- ^ Blue & Naden 2004, p. 32.

- ^ Murray 1908, p. 61.

- ^ Minderhout 2013, pp. 37–38.

- ^ a b c Murray 1908, p. 64.

- ^ Murray 1921, pp. 289–290.

- ^ a b Murray 1921, p. 290.

- ^ a b Donehoo 1918, p. 132.

- ^ a b c Minderhout 2013, p. 38.

- ^ Twigg 2005, p. 32.

- ^ Twigg 2005, p. 24.

- ^ "New York New Deal Art". wpamurals.com. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ^ Twigg 2005, p. 31.

Bibliography[]

- Blue, Rose J.; Naden, Corinne J. (2004). Exploring the St. Lawrence River Region. Chicago, Illinois: Raintree. p. 32. ISBN 141090337-0.

- Donehoo, George P. (1918). "Report of the Work of the Susquehanna Archaeological Expedition". Second Report of the Pennsylvania Historical Commission. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: New Era Printing Company.

- Lenik, Edward J. (2009). Making Pictures in Stone: American Indian Rock Art of North America. Tuscaloosa: The University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-1629-7.

- Minderhout, David J. (2013). Native Americans in the Susquehanna River Valley, Past and Present. Lewisburg: Bucknell University Press, co-published with The Rowman & Littlefield Pub. Group, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61148-487-8.

- Murray, Louise Welles (1908). A History of Old Tioga Point and Early Athens, Pennsylvania. Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: The Raeder Press.

- Murray, Louise Welles (July–September 1921). "Aboriginal Sites in and Near "Teaoga," Now Athens, Pennsylvania". American Anthropologist. American Anthropological Association. 23 (3): 183–214. doi:10.1525/aa.1921.23.2.02a00070. JSTOR i227229.(subscription required)

- Parkman, Francis (1897). Pioneers of France in the New World: France and England in North America. Part First, Volume II. Little Brown and Company, Boston. p. 235.

- Twigg, Deborah (Fall 2005). "Revisiting the Mystery of "Carantouan" and Spanish Hill". Pennsylvania Archaeologist. Society for Pennsylvania Archaeology. 75 (2).

External links[]

- Archaeological sites in Pennsylvania

- Landforms of Bradford County, Pennsylvania

- Geologic formations of Pennsylvania

- Archaeological controversies