Stadium of Domitian

| Stadium of Domitian | |

|---|---|

Arcade of the Stadium of Domitian | |

| Location | Regio XI Circus Maximus |

| Built in | AD 80 |

| Built by/for | Domitian |

| Type of structure | Stadium |

| Related | List of ancient monuments in Rome |

Stadium of Domitian | |

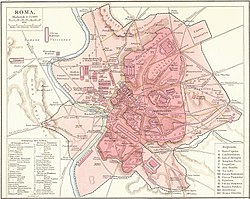

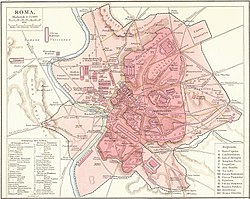

The Stadium of Domitian (Italian: Stadio di Domiziano), also known as the Circus Agonalis, was located to the north of the Campus Martius in Rome, Italy. The Stadium was commissioned around AD 80 by the Emperor Titus Flavius Domitianus as a gift to the people of Rome, and was used mostly for athletic contests.

History[]

Construction and design[]

The Stadium of Domitian was dedicated in AD 86, as part of an Imperial building programme at the Field of Mars, following the damage or destruction of most of its buildings by fire in AD 79. It was Rome's first permanent venue for competitive athletics. It was patterned after the Greek model and seated approximately 15,000 - 20,000 – a smaller, more appropriate venue for foot-races than the Circus Maximus, although a catalogue complied at the end of the 4th century recorded that the stadium's seating capacity was 33,080 persons.[1][2][3] The substructures and support frames were made of brick and concrete – a robust, fire-retardant and relatively cheap material – clad in marble. Stylistically, the Stadium facades would have resembled those of the Colosseum; its floor plan followed the same elongated, U-shape as the Circus Maximus, though on a much smaller scale. Various modern sources estimate the arena length to have been approximately 200 – 250 metres, the height of its outer perimeter benches as 30 m (100 ft) above ground level and its inner perimeter benches as 4.5 m (15 ft) above the arena floor.[4] This arrangement offered a clear view of the track from most seats. The typically Greek layout gave the Stadium its Latinised Greek name, in agones (the place or site of the competitions). The flattened end was sealed by two vertically staggered entrance galleries and the perimeter was arcaded beneath the seating levels, with travertine pilasters between its cavea (enclosures). The formation of a continuous arena trackway by a raised "spina" or strip has been conjectured.[5]

The Stadium of Domitian was the northernmost of an impressive series of public buildings on the Campus Martius. To its south stood the smaller and more intimate Odeon of Domitian, used for recitals, song and orations. The southernmost end of the Campus was dominated by the Theater of Pompey, restored by Domitian during the same rebuilding program.[6]

Uses[]

The Stadium was used almost entirely for athletic contests. For "a few years", following fire-damage to the Colosseum in AD 217, it was used for gladiator shows.[7] According to the Historia Augusta's garish account of Emperor Elagabalus, the arcades were used as brothels[8] and the emperor Severus Alexander funded his restoration of the Stadium partly with tax-revenue from the latter.[9] In Christian martyr-legend, St Agnes was put to death there during the reign of the emperor Diocletian, in or near one of its arcades. With the economic and political crises of the later Imperial and post-Imperial eras, the Stadium seems to have fallen out of its former use; the arcades provided living quarters for the poor and the arena a meeting place. It may have been densely populated: "With the decline of the city after the barbarian invasions, the rapidly dwindling population gradually abandoned the surrounding hills and was concentrated in the campus Martius, which contained the main part of Rome until the new developments in the nineteenth century."[10] Substantial portions of the structure survived into the Renaissance era, when they were mined and robbed for building materials.

Legacy[]

The Piazza Navona sits over the interior arena of the Stadium. The sweep of buildings that embrace the Piazza incorporates the Stadium's original lower arcades. They include the most recent rebuilding of the Church of Sant'Agnese in Agone, first founded in the ninth century at the traditional place of St. Agnes' martyrdom.[11]

See also[]

Notes[]

- ^ Gregorovius, Ferdinand, History of the City of Rome in the Middle Ages, Vol. 1, (1894), pg. 47

- ^ Humphrey, John H., Roman Circuses: Arenas for Chariot Racing, University of California Press, 1986, p.3: link Humphrey gives a seating capacity estimate of 150,000 for the Circus Maximus.

- ^ Contemporaneous references to seating capacity are implausibly high if their reference to loci is assumed to mean "seating places", but less so when taken as "per foot run of seating". Regarding the seating at the Circus Maximus, "the Notitia [says] that in the fourth century it had 385,000 loca [which] has been interpreted to mean that number of running feet of seats, which would accommodate about 200,000 spectators." See Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby): A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, London: Oxford University Press, 1929.p. 119: Bill Thayer's website link

- ^ The slightly higher estimate for seating numbers, and the lower estimate for arena length are in Richardson, L., A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. pp. 366 - 7, showing reconstructed ground plan: convenience link

- ^ Arena seating and length estimates from Samuel Ball Platner (as completed and revised by Thomas Ashby): A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome, London: Oxford University Press, 1929, p.496: Bill Thayer's website link

- ^ Platner, Ibid, Campus Martius: Bill Thayer's website link

- ^ Cassius Dio, Roman History, (epitome), 78, 25.2: link This ruinous Colosseum fire was caused by lightning – one of many divine signs to anticipate the death of the emperor Macrinus.

- ^ Historia Augusta, The Life of Elagabalus, 26.3.

- ^ Richardson, L., A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992. pp. 366 - 7 has "numerous brothels... and probably shops and workshops as well," like the Circus Maximus.

- ^ Platner, Ibid, 94: Bill Thayer's website link

- ^ Mariano Armellini, Le Chiese di Roma dal secolo IV al XIX, pubblicato Dalla Tipografia Vaticana, 1891: (Italian only; Bill Thayer's website link)

- 86

- 80s establishments in the Roman Empire

- 1st-century establishments in Italy

- Buildings and structures completed in the 1st century

- Ancient Roman circuses in Rome

- Domitian

- Rome R. VI Parione