Stand-up comedy

| Stand-up comedy | |

|---|---|

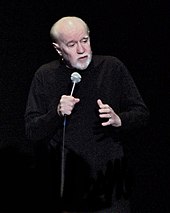

George Carlin performing his stand-up comedy routine in April 2008 | |

| Medium | Performing arts, talk radio, live action, social media |

| Ancestor arts | Monologist, humorist, clown, tummler |

| Descendant arts | Podcaster, social media influencer |

| Originating culture | the scene (geographical) |

| Performing arts |

|---|

|

Stand-up comedy is a comedy performance and narrative craft whereby a comedian communicates to a live audience, speaking directly to them through a microphone.[1][2][3] The performer is commonly known as a comic, stand-up comic, comedian, comedienne, stand-up comedian, or simply a stand-up.[4] Stand-up comedy is a dialogic monologue, or a grouping of humorous stories, jokes, and one-liners, typically called a shtick, routine, act, or set.[17] Stand-ups may fuse props, music, magic tricks, or ventriloquism.[18] Stand-up comedians perform quasi-autobiographical and fictionalized extensions of their offstage selves.[30]

Overview[]

Stand-up comedy can be performed in comedy clubs, comedy festivals, bars, pubs, nightclubs, colleges, theatres, niche locations, etc.[31][32] Stand-up is also distributed commercially via live action, audio, streaming, etc.[33][4][34]

It can take an amateur comedian about 10 years to perfect the technique needed to be a professional comedian;[35][36][37] this is a constant process of learning through failure.[43]

Genres[]

Just as within any art form, stand-up has multiple genres and styles, with their own formats, unwritten rules, and target audience. Some of these include:

- Alternative comedy which defines itself against the backdrop of mainstream comedy

- Character comedy where the comedian performs partly or throughout their set as one or more invented characters.

- Comedy music where a comedian will mostly or significantly use a music instrument or their voice within their set.

- DIY Comedy which is a "new alternative" reaction to Alternative Comedy.[44]

- Improvised comedy where the bulk of the comedian's material is invented on-stage, often based on information or events in the audience.

- Insult comedy based on ridiculing the audience or a 'common enemy', deriving humour from those outside of the insult enjoying the joke.

- Observational comedy uses normality and social norms as a type of relatable fulcrum.[45][25][46]

- Political satire where the political figures, establishment or ideologies are subject of ridicule.

- Surreal humour often including long, meandering stories or unusual characters

Circuits[]

Bookers book comedians on the basis of how clean or dirty their act is, their popularity, and their ability to draw an audience.[53]

A comedy venue, like a music venue or sports venue, is a building, structure, or place where comedy takes place.

Stand-up comedy show[]

Audiences expect a stand-up comedian to provide a constant stream of laughs,[58] and a performer may feel pressured to deliver, especially during the first two minutes.[65] The late Phyllis Diller holds the record for most laughs per minute, at twelve laughs per minute.[66][67][68]

Basic format[]

Opener, feature, headliner[]

The host, compère (UK), master of ceremonies (MC or emcee), mistress of ceremonies, or opener, performs for around ten minutes, warming up the audience, interacting, making announcements, and introducing the other performers; this is followed by the middle/feature who does around thirty minutes; then, the headliner, performs for roughly an hour.[75] An opener can also double as a feature for travelling headliners.[76][72]

Showcase format[]

Showcase format has a host/MC with several other acts who perform for roughly equal lengths of time.[77]

Festivals[]

Comedy festivals are arts festivals.[78][79] Industry professionals, or scouts, use comedy festivals to seek out new comedians to hire.[80][81][82][83]

Open mic[]

Stand-ups use open mics to practice.[84][85] Industry scouts rarely watch open mics.[86]

Bringer shows[]

Bringer shows are open mics that require amateur performers to bring a specified number of paying guests to receive stage time. Some view this as exploitation.[87][88][89] The guests pay a cover charge and there is often a minimum number of drinks that must be ordered. These shows are often "showcase" format. Different bringer-show venues have different requirements.[90][89]

Guest set[]

A five-to-ten minute, time slot.[91]

Salary[]

Most comedians have day jobs.[96] In a comedian's first five years, they will lose money from traveling and performing.[102]

Stand-ups start getting paid by hosting.[103] While it can take around a decade to make a living at comedy,[99] unknown comedians may achieve great financial success.[104][105][106]

Hosts and MCs are paid $0-$200, depending on location and the time of week (emcees average $25[107]); showcase spots get $10-$75; features get approximately $300-$600; a headliner with no following gets $150-$1500, depending on many factors; headliners with a following or TV credits can make $1,500-$10,000 per show.[108][109][110][111] The headliner makes "10 times" more money than the feature act.[73] Famous headliners get paid from "door deals," or a percentage of the revenue, based on the number of seats sold; these comics rely on their notoriety to fill seats, which makes them more money than headliners with no following.[112][113] Comics will sell merchandise after their shows; this will make up for other expenses, like traveling.[114]

Mark Normand has stated that a set on Conan pays "a couple grand" for five minutes.[115] In 2012, Comedy Central routinely offered $15,000 for a half-hour special.[116] As of 2015, Comedy Central will pay comedians about $20,000 for a thirty-minute set; an hour, Comedy Central special can be up to $150,000;[117] as of 2018, Netflix will pay comedians $26,000+ for a fifteen-minute set; Netflix pays celebrity-comedians different amounts from one another.[118][119]

The cruise-circuit comedian can make up to $10,000 per week,[120] Cruiseliners have both clean comedy and blue comedy at different times during the day, but opinionated political material is frowned upon.[121] some $85,000 per year; and, a college-circuit comedian can make six figures per year or thousands of dollars per gig.[116][122][123] Christian circuit comedy headliners make $1,500-$2,500 per show.[124] Although one source states that newer comics on the national (L.A.) circuit make $1,250-$2,500 per week, another source claims that this is very inaccurate, and the amount of money one makes is closer to $20 for a spot.[125][126]

Famous comedians may pay other professional comedians for jokes and hire them on as writers,[127][128] but many famous comedians do not reveal this, as it is considered a taboo to admit purchasing material for stand-up comedy sets.[129] Comedians may knowingly sell plagiarized jokes.[130]

History[]

Stand-up comedy got its start in the 1840s from the three-act, variety show format of minstrel shows (via blackface performances of the Jim Crow character); Frederick Douglass criticized these shows for profiting from and perpetuating racism.[131][132] Minstrelsy monologists performed second-act, stump-speech monologues from within minstrel shows until 1896, although traces of these racist performances continued to be used until the mid-1900s.[133][134] Stand-up comedy also has roots in various traditions of popular entertainment of the late 19th century, including vaudeville (via minstrel shows, dime museums, concert saloons, freak shows, variety shows, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus), American burlesque (via Lydia Thompson's feminization of the minstrel show, concert saloons, English music halls, and circus clown antics), and humorist monologues like those delivered by Mark Twain in his first (1866) touring show, Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands.[135][136][137][138] Unadulterated, vaudeville monologuist run-times were 10–15 minutes.[139]

The room[]

| Semiotics |

|---|

| General concepts |

|

| Fields |

|

| Methods |

|

| Semioticians |

|

| Related topics |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Emotions |

|---|

|

|

The room is a colloquialism for the space where the interaction between the stand-up and the audience occurs.[146] A comedian will read the room by interpreting signs from the audience.[153] A stand-up will work the room in symbolically interacting with the audience, delivering signs (q.v., POV).[154][155][156] A stand-up will walk the room when punters become so personally offended by a joke that they physically leave the room.[157][158] Playing to the back of the room is an in-joke among comedians.

Soft architecture of the room[]

The quality of the room affects how the audience perceives the stand-up's performance.[163] The flow to the room has a hot and cold cognition.[168] The energy of the room changes with substances.[172] Comedic genres are separated by experiences.[177]

A warm-up comedian (or crowd warmer) warms up cold audiences as the opening act or before the filming of television comedies in front of studio audiences.[164][166][178]

Humor through the room[]

Comedians create psychological tensions in the room that are relieved with laughter.[185] Comedians observe normality and social norms as a type of relatable audience fulcrum.[45][25][46] Punching up and punching down are political terms for the direction in which a joke punches, or who should be the butt of the joke.[186][187][188] It carries with it the assumption that, relative to the comedian's socio-political identity, comedy should punch up at the powerful rather than punch down at the marginalized.[189][190][191]

There is no consensus among the comedy community as to which is most important for getting laughs: persona, material, or fame.[199] A stand-up defines their craft, in part, by how they convince the audience to laugh and by their development of a persona.[207]

The audience[]

Punter is a regional term for a member of the audience.[208] The audience's feedback at a stand-up performance, even from the moment they enter the venue, is instant and crucial for the comedian's ever-changing act.[216] Audience members, in a comedy setting that doesn't have fixed seating, are seated very close to one another.[224]

The comedian's act and set[]

A stand-up comedian frames the tone and mood of the room as a construct of play.[225] Audiences license the suspension of normal social conventions. Stand-ups appeal to telling jokes for the sake of joking. Stand-ups design their sets through the construction and onstage revision of jokes.[38][144][226]

When a stand-up does well by making the audience collectively laugh in unison, they are killing; if the stand-up is doing poorly, they are dying.[231]

Crowd work[]

Stand-ups use second person to address the audience.[232] Comedians perform crowd work by communicating directly with audience members through forethought, improvisation, or some of both. [233] One result of crowd work is an inside joke.

In stand-up, a heckler is a person who interrupts a comedian's set. Comedians will often have a repertoire of comebacks for hecklers.[234] Comedians rarely get into physical altercations with hecklers.[235][236]

Onstage personality[]

When a professional stand-up is at ease or in stage repose, they still possess the characteristics of a professional stand-up, such as being interesting, entertaining, engaging, and relatable.[241] Mugging is to facially pose in a way that reveals one’s identity and emotions (i.e., common phrase ham-/mug-/clown for the camera)(q.v., chew the scenery).[246] Pointing is when the comic puts an inflection on the laugh-line that comes before the audience reaction.[247][248]

Modern stand-up relies on narrative.[256] Character is tied to narrative.[267] Persona is not a character but a self-managed version of one's offstage personality that comes from onstage, audience feedback.[278] The performer's reputation is a continuity of onstage and offstage image.[279][280][281]

One-person show[]

These performances are stylistically dominated by autobiographical storytelling.[282][283][250] One-person, stand-up comedy shows became popular in the 1990s.[284][285]

The routine[]

Bits (linked jokes) and chunks (linked bits) are an arrangement of interlinked thematic units from within the set or routine.[296] A stand-up routine is a gestalt that emerges from performing interconnected jokes, bits, and chunks to a live audience.[301] Stand-ups structure jokes, bits, and chunks to end on climactic laughter.[306] Comedians often end their jokes with taglines, toppers, or afterthoughts for increased laughter.[311] A segue is the link between jokes.[312][313][314] A callback is a reference to a previous thing that was experienced by the audience during that set, designed to create an inside joke.[318] Bombing refers to when a comedian has failed to get an intended laugh.[319][320]

Intro[]

The opening remarks to a stand-up comedian's set are the hook.[321][60][63]

Stand-up joke[]

Stand-ups deliver canned jokes through the use of thematic narrative structure.[328] A stand-up comedian delivers the joke through the use of timing: the setup and then the punch line, or laugh line.[334] A joke is made of a premise, point of view, and then the reveal.[342] The setup to a joke contains the information needed by the audience in order to understand the punchline.[349] Most of stand-up comedy's jokes are the juxtaposition of two incongruous things.[361] Stand-ups use jester's privilege, or comic license, to feign sincerity for maintaining a close aesthetic distance with the audience (e.g., they frame their stories as having happened "recently").[372] The comedian's delivery of a joke is integral to the process—the comedian's voice, pauses, intonation, inflection, attitude, energy, and other elements.[378] Comedians often include stylistic and comedic devices, such as tropes, idioms, stop consonants, archetypes, soliloquy, expletive infixation, and wordplay.[379][380][381][382] A paraprosdokian is a popular method of joke structuring by using a surprising punchline that causes the listener to reinterpret the setup.[383][384] Stand-ups will often use the rule of three.[385][386][387][388]

A comedian's ideas and jokes will fail nine times out of ten; this may require a comedian to write hundreds of jokes to achieve enough successful ones to fill a set.[393] A stand-up comedian cannot know if their material has succeeded without an audience to give feedback.[398]

Tight five[]

A tight five is a five-minute stand-up routine that is well-rehearsed and consists of a stand-up comedian's best material that reliably gets laughs.[399] It is often used for auditions or delivered when audience response is minimal.[400][401][402] A tight five is the stepping stone to getting a paid spot.[403][404]

Memorization[]

Comics memorize their jokes through the use of on-stage practice/blocking.[405] Some professional stand-ups are known to use a mnemonic device called the method of loci.[406][407] Professionals may use a set list; this is generally hidden (e.g., on a cue card or a stage monitor).[408][409]

Terminology[]

- Chi-chi room

- A chi-chi room may be the ritzy room of an establishment, a small nightclub, or a comedy venue with niche performances.[410][411][412][413]

- Clapter

- Coined by comedian Seth Meyers, a term for when an audience is coaxed to cheer or applaud for a joke, topic, feeling, or opinion that they agree with but that is not funny enough to get a laugh.[414][415][416][417]

- Corpsing

- Corpsing is a regional term for laughing when one is supposed to be playing it straight.

- Hack

- A hack is a pejorative term for a comedian with rushed, unoriginal, low-quality, or clichéd material.[425] One proposed amelioration to hackneyed material is an essay by George Orwell called "Politics and the English Language: The Six Rules".[426]

- Joke theft

- Modern stand-up is predicated upon originality; appropriation and plagiarism are social crimes.[427][428] When someone is accused of stealing a joke, the accused's defense is sometimes cryptomnesia[429] or parallel thinking.[430]

- Smelling the road

- Claiming that one can "smell the road" on a comic is a pejorative phrase for a comedian who has compromised their own originality to get laughs while travelling.[434]

Other media[]

- The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel

List of comedians[]

- List of comedians

- List of humorists

- List of stand-up comedians

- List of musical comedians

- List of Australian comedians

- List of British comedians

- List of Canadian comedians

- List of Filipino Comedian

- List of Finnish comedians

- List of German language comedians

- List of Indian comedians

- List of Italian comedians

- List of Japanese comedians

- List of Mexican comedians

- List of Pakistani comedians

- List of Puerto Rican comedians

Other types of stand-up[]

- Badchen (Yiddish)

- Macchietta — Italian 19th century comedy act

- Manzai — style of Double act comedy in Japan

- — style of stand-up comedy in Japan

- Rakugo — Japanese verbal solo entertainment similar to stand-up comedy, but kneeling instead of standing.[435]

- Tummler (Yiddish)

- Xiangsheng — Chinese traditional stand-up comedy

See also[]

Comedy portal

Comedy portal- 2019 in stand-up comedy

- 2020 in stand-up comedy

- Alter ego

- Artistic license

- Auxesis (figure of speech)

- Bandwagon effect

- Celebrity culture

- Comedy troupe

- Diegesis

- Eutrapelia

- Flow state

- Flyting

- Generalized other

- Green room

- Groupthink

- Improvisational theatre

- Interpersonal communication

- List of humor research publications

- Looking-glass self

- Magical thinking

- Metatheatre

- Non-sequitur

- Paradoxe sur le comédien

- Radio comedy

- Roast

- Self-awareness

- Set and setting (drug experience)

- Shibboleth

- Social skills

- Situation comedy

- Stage name

- Straight man

- Superficial charm

- Tag and one-liner (graffiti)

- The Comedian's Comedian with Stuart Goldsmith

- The Clown's Prayer

- The History of Comedy

- Theories of humor

- Unreliable narrator

- WTF with Marc Maron

- You Made It Weird with Pete Holmes

References[]

- ^ Mintz, Lawrence E. (Spring 1985). "Special Issue: American Humor" (PDF). American Quarterly. The Johns Hopkins University Press. 37 (1): 71–72. doi:10.2307/2712763. JSTOR 2712763. Retrieved 2 August 2020.

A strict, limiting definition of standup comedy would describe an encounter between a single, standing performer behaving comically and/or saying funny things directly to an audience, unsupported by very much in the way of costume, prop, setting, or dramatic vehicle. Yet standup comedy's roots are ... entwined with rites, rituals, and dramatic experiences that are richer, more complex than this simple definition can embrace. We must ... include seated storytellers, comic characterizations that employ costume and prop, team acts[,] ... manifestations of standup comedy routines ... such as skits, improvisational situations, and films ... and television sitcoms ... however our definition should stress relative directness of artist/audience communication and the proportional importance of comic behavior and comic dialogue versus the development of plot and situation

- ^ Shouse, Eric (2020). "Person, Persona, and Act: The Dark and Light Sides of George Carlin, Richard Pryor, and Robin Williams". In Oppliger, Patrice A.; Shouse, Eric (eds.). The Dark Side of Stand-up Comedy. United Kingdom: Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 34. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37214-9_2. ISBN 978-3-030-37213-2. S2CID 216341557.

[The microphone allows] comedians to speak in a 'natural register' in a manner that closely resemble[s] everyday conversation ... As a result, stand-up comics can create the 'illusion of intimacy' with a large group of people ... The intimate tone and style of address are further amplified by a context in which 'theatrical stagecraft [is kept] to a bare minimum'

- ^ Brodie, Ian (2008). "Stand-up Comedy as a Genre of Intimacy". Ethnologies. Cape Breton University. 30 (2): 156–157. doi:10.7202/019950ar. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

[S]tand-up comedy ... cannot exist without technological advances ... what distinguishes it as a whole from other forms of verbal comedy, and where one can deduce its origins, is the advanced use of the microphone ... antecedents and forebears are suggested ranging from the court jester to Mark Twain and Will Rogers. Such suggestions of ancestry are not without merits, but as a form or, more precisely, as an emic genre with an attendant set of expectations, including the dialogic properties ... stand-up comedy, contemporary or otherwise, does not exist without amplification.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Fisher, J Tommy Cooper: Always Leave Them Laughing ISBN 978-0-00-721511-9

- ^ Fallatah, Wafaa (2017). "Bilingual creativity in Saudi stand-up comedy". World Englishes. 36 (4): 670. doi:10.1111/weng.12239. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

By stand-up comedy, I refer to the special genre of comedy where an individual comedian uses his or her shared culture, historical background, social assumptions, and nuances of language to provide live entertainment through a monologue, consisting of jokes, anecdotes, and sketches intended to make an audience laugh (Stevenson 2010)

- ^ Lindfors, Antti (6 May 2019). "Cultivating Participation and the Varieties of Reflexivity in Stand-Up Comedy". University of Turku, Finland. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 29 (3): 282–283. doi:10.1111/jola.12223. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

To begin with, indiscriminate in address and open to every (paying) customer, stand-up comedy can be regarded as closer to public rhetoric rather than actual dialogue (see also Peters 1999, chapter 1).

- ^ Lintott, Sheila (2020). "Stand-Up Comedy and Mental Health: Critiquing the Troubled Stand-Up Stereotype". In Oppliger, Patrice A.; Shouse, Eric (eds.). The Dark Side of Stand-up Comedy. United Kingdom: Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 215. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37214-9_10. ISBN 978-3-030-37213-2. S2CID 216475748.

it is inherent to the very nature of stand-up that they [stand-ups] convincingly perform as if they are simply being themselves and talking off the cuff

- ^ Lee, Judith Yaross (2006). "Mark Twain as a Stand-up Comedian". The Mark Twain Annual. Penn State University Press. 4 (4): 5. JSTOR 41582220.

[S]tand-up is marked above all by face-to-face interaction that imitates a (mostly one-way) conversation.

- ^ Seizer, Susan (2011). Stewart Huff. "On the Uses of Obscenity in Live Stand-Up Comedy". Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 84 (1): 213. doi:10.1353/anq.2011.0001. JSTOR 41237487. S2CID 144137009.

[S]tand-up is not so much public speech as it is talk. Though it may be 'heavily one-sided,' it is nevertheless a dialogic form 'that allows for reaction, participation, and engagement on the part of those to whom the stand-up comedian is speaking'

- ^ Wayne Federman (9 July 2019). "S2 Ep. 06: Meltdown". The History of Standup (Podcast). Dana Gould. The Podglomerate. Event occurs at 21:40-21:54. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

A low ceiling and proximity to the stage is important because standup comedy is not a performance. It is a conversation in which the comedian does all of the talking.

- ^ Morris, Andrea (26 July 2018). "A Robot Stand-Up Comedian Learns The Nuts And Bolts Of Comedy". Forbes. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

[A lot of] stand-up comedy ... as a general art form ... is pre-scripted

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 16. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

Jerry Seinfeld explains: 'Comedy is a dialogue, not a monologue—that's what makes an act click. The laughter becomes the audience's part, and the comedian responds'

- ^ Stewart Lee (3 July 2013). On Not Writing (Lecture) (YouTube). St Edmund Hall: University of Oxford. Event occurs at 48:54-48:58. Retrieved 13 February 2019.

On the whole, you have to give the illusion that it's a dialogue

- ^ Dean, Greg (2000). Step by Step to Stand-up Comedy. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann. p. 190. ISBN 0-325-00179-0.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 90. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

A comic's material about his life may have some connection to reality, but basically an act is just that, an act—it's a fictionalized account with a few actual facts thrown in to make the act believable and, perhaps, more relevant to people's lives.

- ^ Brodie, Ian (2014). "Stand-Up Comedy and a Folkloristic Approach". A Vulgar Art: A New Approach to Stand-up Comedy. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-62846-182-4.

[S]tand-up comedy is a dialogic form. No matter how one-sided the conversation between the performer and the audience might be, there is a required reciprocity between performer and audience.

- ^ [5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16]

- ^ Martin, Steve (2007). Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life. New York: Scribner. pp. 40–42. ISBN 978-1-4165-5364-9.

I was demonstrating tricks eight to twelve hours a day

- ^ Lee, Judith Yaross (2006). "Mark Twain as a Stand-up Comedian". The Mark Twain Annual. Penn State University Press. 4 (4): 4. JSTOR 41582220.

Stand-up comedians purport to speak autobiographically and in their own voice while engaging in apparently authentic, if not convincingly spontaneous, communication with the audience, and their punch lines typically cap extended anecdotes and observations instead of one-line jokes.

- ^ Smith, Daniel R. (2018). "Part II: Synthetic[:] Representation: Stand-up: representing whom?". COMEDY AND CRITIQUE: Stand-up comedy and the professional Ethos of laughter. Bristol Shorts Research. UK: Bristol University Press. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-5292-0015-7.

[S]tand-up comedians (often) appear 'as themselves' ... stand-up comedy is a form of theatre; it is not life ... stand-up is about the re-presentation of self as if it were everyday life

- ^ Ajaye, Franklyn (2002). Comic Insights: The Art of Stand-up Comedy. Quote by Jerry Seinfeld. Los Angeles: Silman-James Press. p. 199. ISBN 1-879505-54-1.

That's the goal—to become yourself.

- ^ Mendrinos, James (2004). The Complete Idiot's Guide to Writing Comedy. NY, New York: ALPHA: A member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. p. 12. ISBN 1-59257-231-6.

- ^ Munro, David (2018). "The Art of the Joke". CRAFTSMANSHIP Quarterly: The Architecture of Excellence. The Craftsmanship Initiative. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Evans, Bradford (7 August 2012). "Stand-Up Comedians and Their Alternate On-Stage Personas". Vulture: Devouring Culture. NEW YORK MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 15 March 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp. 90–91. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

[A stand-up's] act [is a] fictionalized account with a few actual facts thrown in to make the act believable and, perhaps more relevant to people's lives ... Every stand-up goes onstage as a character to some extent. Some may adopt a persona that's very similar to their own personality, but it's still a separate entity ... even observational comics ... use truth ... as a foundation on which to build jokes by taking the truth to its farthest [sic] extreme.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 262. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

(loosely) autobiographical comedy is the dominant form of stand-up today.

- ^ Ajaye, Franklyn (2002). Comic Insights: The Art of Stand-up Comedy. Gary Shandling. Los Angeles: Silman-James Press. p. 209. ISBN 1-879505-54-1.

I [Gary Shandling] think you can only be on stage what you are in real life.

- ^ Katzif, Mike (16 November 2018). "Mo Amer: Working The Classroom Comedy Circuit". NPR. Retrieved 11 September 2019.

[I]f you're not real ... people will sniff that out.

- ^ Wilde, Larry (2000) [1968]. "Johnny Carson". Great Comedians Talk About Comedy. Johnny Carson. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Executive Books. p. 168. ISBN 0-937539-51-1.

Larry Wilde: Charlie Chaplin in a Life magazine story said, 'You cannot be funny without an attitude. Being without an attitude in comedy is like something amiss in one's make-up.' What exactly is a comic attitude? ... [Johnny Carson:] Generally, it is your outlook on things. It is, in a way, an extension of your personality.

- ^ [19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29]

- ^ Louis C.K. (22 April 2011). Talking Funny (Film). Event occurs at 11:55-12:12.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Chris Dipetta. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 68. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

The average club seats [250] people

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2015). Why Stand-up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-4725-7893-8.

Laughter and ticket or DVD sales are, therefore, not universally considered the most important markers of success, and nor is laughter the only thing ever demanded of comedians.

- ^ Fearless delivery sets Will Ferrell apart. The Denver Post, 24 June 2005. Accessed on 29 March 2010.

- ^ Ajaye, Franklyn (2002). Comic Insights: The Art of Stand-up Comedy. George Wallace. Los Angeles: Silman-James Press. p. 240. ISBN 1-879505-54-1.

How did you answer them? 'By being George Wallace, and finding out who you are as a comedian. And that takes between seven and eleven years.'

- ^ Ajaye, Franklyn (2002). Comic Insights: The Art of Stand-up Comedy. Jerry Seinfeld. Los Angeles: Silman-James Press. p. 200. ISBN 1-879505-54-1.

How long did it take you to figure out your individual comedic essence? 'I'd [Jerry Seinfeld] say ten years.'

- ^ Louis C.K., Charlie Rose (7 May 2014). Louis C.K. (Interview) (TV Show). HBO. Event occurs at 3:59-4:03. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

A stage presence comes pretty quickly [but] how to write jokes and how to generate material and know it's going to work; [concerning these, the] first ten years are building the [base] skills

- ^ Jump up to: a b Naessens, Edward David (2020). "Busting the Sad Clown Myth: From Cliché to Comic Stage Persona". In Oppliger, Patrice A.; Shouse, Eric (eds.). The Dark Side of Stand-up Comedy. United Kingdom: Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 227. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37214-9_11. ISBN 978-3-030-37213-2. S2CID 216338873.

Each minute of performance is backed up by countless hour of hit-and-miss writing, editing, road-testing, and practice. While some say they do not actually 'write down' their material ... [in actuality] they run it over consistently in their heads.

- ^ Bobby Lee (interviewee) (2017). Dying Laughing (Motion picture). Gravitas Ventures. Event occurs at 1:02:38-1:02:48.

Bombing is a necessary event. It's the only way one gets better, but every time it happens, it's very painful.

- ^ John Thomson (interviewee) (2017). Dying Laughing (Motion picture). Gravitas Ventures. Event occurs at 1:02:52-1:02:55.

You've got to die to get good.

- ^ Seabaugh, Julie (18 March 2014). "Hannibal Buress: 'Bombing Can Be Good'". The Village VOICE. Hannibal Buress. VILLAGE VOICE, LLC. Retrieved 4 February 2019.

Yeah, bombing can be good ... you grow up and realize it's about continuing to work. It's about making progress.

- ^ Fox, Jesse David (11 May 2021). "Who Should John Mulaney Be Now?". Vulture: Devouring Culture. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

[Chris] Rock's process involves intentionally bombing early on, so that the laughs don't interfere with his read on how the audience feels about certain topics.

- ^ [38][39][40][41][42]

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2015). Why Stand-up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-1-4725-7893-8.

[T]he ‘new alternative’ known as DIY comedy. It opposed the commercialist ethos that had come to dominate alternative comedy and responded to an ‘increasing sense of purposelessness and loneliness among young persons in Western society’.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Quirk, Sophie (2015). Why Stand-up Matters: How Comedians Manipulate and Influence. New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. p. 154. ISBN 978-1-4725-7893-8.

Observational comedy works by mocking 'normal' behaviours but, even as it does so, it often affirms and promotes a fixed idea of what 'normal' is.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Double, Oliver (2014) [2005]. Getting the Joke: the inner workings of stand-up comedy (2nd ed.). New York: Bloomsbury Methuen Drama. p. 208. ISBN 978-1-4081-7460-9.

Eddie Izzard observes: 'Your observations need to be something that people can relate to, for the audience to pick up on it.'

- ^ Seizer, Susan (2011). "On the Uses of Obscenity in Live Stand-Up Comedy". Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 84 (1): 212. doi:10.1353/anq.2011.0001. JSTOR 41237487. S2CID 144137009.

In the stand-up business, 'dirty' and 'clean' are treated as polar opposites. Swearing is the difference between the two, and bookings are based on the distinction. Club owners, event sponsors, and media executives let comics know, usually through bookers or agents, whether they will hire someone who works blue or whether they are interested in those who will refrain from uttering obscenities.

- ^ Shouse, Eric (2020). "Shit Talking and Ass Kicking: Heckling, Physical Violence and Realistic Death Threats in Stand-Up Comedy". In Oppliger, Patrice A.; Shouse, Eric (eds.). The Dark Side of Stand-up Comedy. United Kingdom: Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 253. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37214-9_12. ISBN 978-3-030-37213-2. S2CID 216523473.

Profanity is commonplace in contemporary stand-up comedy (so much so that 'clean comedy' is a marketable commodity).

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (November 2011). "Containing the Audience: The 'Room' in Stand-Up Comedy" (PDF). University of Kent, UK. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies. 8 (2): 221. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

Across the UK, there are hundreds of small, informal gigs that run on enthusiasm, for little or no financial profit. It is in these that most comedians get their start. They learn their craft and gradually work their way up through larger audiences and more prestigious venues. The lucky minority come to a point where they can tour their own show, their fame perhaps fuelled by appearances on television. The very few become famous enough to graduate to the arena gigs or produce a best-selling DVD. Importantly, it is the live circuit of small-to-medium gigs which fuels the upper echelons of the comedy industry, training and nurturing the talent that big business will adopt. In this sense, those small-to-medium rooms are fundamental to all levels of stand-up production.

- ^ Brodie, Ian (2014). "Stand-Up Comedy Broadcasts". A Vulgar Art: A New Approach to Stand-up Comedy. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-62846-182-4.

Obscenity and other risky material are not inherently part of stand-up comedy, but their avoidance can require a self-censoring and circumnavigation of certain topics that might not be present in conversation among intimates ... [t]ogether the performer and the audience negotiate what is appropriate and what is inappropriate.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Seizer, Susan (2011). "On the Uses of Obscenity in Live Stand-Up Comedy". Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 84 (1): 211–212. doi:10.1353/anq.2011.0001. JSTOR 41237487. S2CID 144137009.

[I]n a bar, dirty language is not out of place at all ... Audiences attending live stand-up in such night spots expect to hear speech onstage that would be otherwise, and elsewhere, unmentionable ... The easy way for a comic to meet such expectations—and here I employ a phrase commonly used in the business itself—is to tell 'dick jokes.' The phrase refers metonymically to a whole category of sex jokes in which 'dirty' words are used to refer directly to 'dirty' body parts ... as well as to acts and sexual functions ... Among insiders, comics who tell dick jokes are considered hacks, and the laughs they raise cheap. The self-respecting road comic tries to come up with original material that not only audiences but also their peers—those with whom they work and those who book their work—will appreciate

- ^ Creviston, James (2019-10-15). "What Is Considered Clean Comedy (And Why It Matters)". Comedypreneur. Schema.org. Retrieved 21 April 2021.

- ^ [47][48][49][50][51][52]

- ^ Chris Rock (interviewee) (2017). Dying Laughing (Motion picture). Gravitas Ventures. Event occurs at 11:24-11:31.

A lot of comedians just want laugh, laugh, laugh ... every, what is it, 15 seconds they say?

- ^ Nevins, Jake (4 October 2017). "Learning laughter: an expert's guide on how to master standup comedy". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

Comedy club audiences ... expect upwards of four laughs per minute.

- ^ Roye, Steve. "How Many Jokes Are In A Minute Of Stand-up Comedy Material?". Stand-up Comedy Tips. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

If a comedian wants to generate headliner laughter levels, they need to average 4-6+ laughs per minute.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp. 253–254. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

As each comic's usage of material varies (some say they use as few as two jokes a minute, other comics say they need a laugh every fifteen seconds or the act goes 'in the toilet')

- ^ [54][55][56][57]

- ^ Frances-White, Deborah; Shandur, Marsha (2016). Off the Mic: The World's Best Stand-up Comedians Get Serious About Comedy. Stephen K Amos. NY, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 209. ISBN 978-1-4725-2638-0.

The first two minutes is very important with a stand-up

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pete Lee (2017). I Need You To Kill (Motion picture). Comedy Dynamics. Event occurs at 31:27-31:56.

I call the first two minutes, your flash. And that's where you ... go up there and ... hook them with whatever material it is, so that they know exactly what's funny about you and they trust you and they'll come along with you for everything.

- ^ MacInnes, Paul (15 August 2004). "How can he show his face?". The Guardian. Karen Koren. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

If you don't make them laugh in the first two minutes, you're fucked

- ^ Neill, Geoffrey (22 December 2015). Hitting Your Funny Bone: Writing Stand-up Comedy, and Other Things That Make You Swear. San Bernardino, CA. p. Chapter 5. ISBN 9781515180661.

If you have a strong first minute ... the minutes that follow will be great, too.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wilde, Larry (2000) [1968]. "Joey Bishop". Great Comedians Talk About Comedy. Joey Bishop. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Executive Books. p. 107. ISBN 0-937539-51-1.

[Joey Bishop:] As the unknown [comedian], you've got to make a compromise and the compromise is in the first few minutes—to get their attention. You are just a salesman then. Once you've got their attention, you can then do your type of comedy.

- ^ See also Captatio benevolentiae

- ^ [59][60][61][62][63][64]

- ^ Carter, Judy (2001). The Comedy Bible. Quote from Phyllis Diller, 'who is listed in The Guinness Book of World Records as having gotten the most laughs per minute of any comic alive or dead'. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7432-0125-4.

I [Phyllis Diller] actually got twelve laughs in one minute from an audience ... Most comics do setup, payoff, setup, payoff, in other words six jokes per minute. In my case of twelve, one setup got twelve payoffs.

- ^ Gorman, Steve (20 August 2012). "Pioneering comedian Phyllis Diller dies at age 95". Reuters. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

Diller prided herself on keeping her jokes tightly written and boasted that she held a world record for getting 12 laughs a minute.

- ^ King, Susan (22 December 2006). "Diller can still pack a punch line". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

[Phyllis Diller] still holds the Guinness Book of World Records for doling out 12 punch lines a minute.

- ^ Malone, Michael. "8 Rules to Emceeing a Comedy Show". Malone Comedy. Wav Records. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

- ^ Durham, Rob (2011). Don't Wear Shorts on Stage: the stand-up guide to comedy. Middletown, DE. pp. 67–68. ISBN 9781468004847.

- ^ Rutter, Jason (1997). "6.3 Compere's Introduction" (PDF). Stand-up as Interaction: Performance and Audience in Comedy Venues. Department of Sociology. CORE (PhD). University of Salford: Institute for Social Research. pp. 149–150. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

In comedy venues, proceedings are managed and organised throughout the performance by a compere who acts as an anchor for the evening's events in the venue. Comperes are more than just an announcer who brings on the acts. They provide continuity between acts who often have divergent styles and or different performance skills; they perform routines between acts using their own material; they pass comment on the performers; they share details of the evening itinerary, they may run a joke competition for the audience, and they encourage the audience's participation. In short, the compere acts to frame a series of performances into a single event.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Seizer, Susan (2011). "On the Uses of Obscenity in Live Stand-Up Comedy". Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 84 (1): 215–216. doi:10.1353/anq.2011.0001. JSTOR 41237487. S2CID 144137009.

On this [road comedy] circuit, shows generally consist of three to four comics: Headliner, Feature act, Opener and/or Emcee (i.e., Master of Ceremonies). The Headliner does roughly an hour of original material. The Feature act does 25-30 minutes. The Opener has a ten minute slot, and the Emcee squeezes in a joke or two between acts (if the Opener is not also acting as the Emcee) ... transitioning between ranks is usually a matter of years of practice at each stage.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Rosenfield, Stephen (2018). Mastering Stand-Up: The Complete Guide to Becoming a Successful Comedian. Chicago, Illinois: Chicago Review Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-1-61373-692-0.

- ^ Ron White (2018). Ron White: If you Quit Listening, I'll Shut Up (Motion Picture). Event occurs at 39:21-39:41. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

[T]raditionally in American comedy clubs, there's three acts: there's an opening act ... a feature act ... and [then] a headliner

- ^ [69][70][71][72][73][74]

- ^ Martin, Steve (2007). Born Standing Up: A Comic's Life. New York: Scribner. pp. 136, 139. ISBN 978-1-4165-5364-9.

One week, I opened for a show ... I was now capable of doing two different twenty-five-minute sets per evening

- ^ Shydner, Ritch; Schiff, Mark, eds. (2006). "A Little Comedy From The Audience: Vic Henley". I Killed: True Stories of the Road From America's Top Comics. Vic Henley (First Paperback ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 222. ISBN 978-0-307-38229-0. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

The Comedy Store in London ... [is] a showcase format, with a host and five comics doing sets, with ... [a] guest thrown in from time to time.

- ^ Brown, Georgia (16 March 2007). "Five top comedy festivals around the world". The Guardian. Guardian News & Media Limited. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Bakare, Lanre (8 July 2020). "No joke: 77% of comedy venues in UK face closure within a year, finds survey". The Guardian. UK. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

Unlike theatre, opera or the visual arts, comedy is not supported by Arts Council England and does not receive funding from the Department for Digital, Culture, Music, and Sport (DCMS).

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2018). The Politics of British Stand-Up Comedy: The New Alternative. Palgrave Studies in Comedy. London, UK: palgrave macmillan. p. 99. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01105-5. ISBN 978-3-030-01104-8. LCCN 2018956867.

Friedman notes the manipulative power of the comedy scouts whose task it is to pluck talent from the great wash of Edinburgh Fringe offerings and—in a more covert function—direct those comedians towards the audience that the scout decides is the comedian’s natural fit

- ^ Frances-White, Deborah; Shandur, Marsha (2016). Off the Mic: The World's Best Stand-up Comedians Get Serious About Comedy. Jim Jefferies. NY, New York: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-4725-2638-0.

Go to festivals, because that's where you get noticed by the media ... [and] gauge [yourself against] everybody else.

- ^ Ajaye, Franklyn (2002). Comic Insights: The Art of Stand-up Comedy. Buddy Mora. Los Angeles: Silman-James Press. p. 280. ISBN 1-879505-54-1.

I [Buddy Morra] go to the Montreal and Aspen comedy festivals, but I haven't seen much that's knocked me out.

- ^ Mendrinos, James (2004). The Idiot's Complete Guide To Comedy Writing. 375 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014: Alpha: A member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc. p. 199. ISBN 1-59257-231-6.

Jim McCue, the founder of The Boston International Comedy and Movie Festival, spoke about the role of the festival in the industry: 'A festival is a great way to get attention for someone who might not have the connections other people do. This festival is constantly looking for under-appreciated talent. Hopefully, we can do our part and let people see the next generation of comedy genius.'

CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Oswalt, Patton (14 June 2014). "A Closed Letter to Myself About Thievery, Heckling and Rape Jokes". Patton Oswalt. Patton Oswalt. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

Open mikes are where, as a comedian [like Daniel Tosh and his controversy], you're supposed to be allowed to fuck up.

- ^ Gillota, David (2019). "Reckless Talk: Exploration and Contradiction in Dave Chappelle's Recent Stand-Up Comedy". Studies in Popular Culture. Popular Culture Association in the South. 42 (1): 1–22. JSTOR 26926330. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

Chappelle’s meta-commentary—in which he articulates stand-up comedy as a space for risk, uncertainty, and inconsistency

- ^ Schaefer, Sara (16 March 2012). "Advice to a Young Comedian (& Myself)". Sara Schaefer. Archived from the original on 24 February 2020. Retrieved 1 February 2019.

the next day, my friend who was also on the show ['in a theatre above a porn shop across from the Port Authority'], told me a scout from casting at Fox was in the audience and they wanted to meet with him.

- ^ Dunican, Angus (10 September 2012). "What do 'bringer' shows REALLY bring to the circuit?". Chortle. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

it gets tarred with the brush of new-act exploitation and lumped in with less scrupulous nights and the insidious blight of pay-to-play ... [but] I, personally, have found it to be a very nice room.

- ^ Kelly-Clyne, Luke (20 September 2018). "I Want Out How to Leave the Boring Job You Don't Like and Start Your Comedy Career". Vulture: Devouring Culture. NEW YORK MEDIA LLC.

In order to get stage time at [bringer shows] ... you [have to] bring ... 5 to 15 friends, each of whom must show up and agree to buy at least two drinks ... Some people think bringers are a scam, and they kind of are. They're a cash grab for club owners

- ^ Jump up to: a b Strauss, Neil (24 January 1999). "My Brief, Weird Life as a Stand-Up Comic". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 February 2019.

- ^ Richardson, Jim (11 December 2013). "Evil "Bringer Shows" & "Pay-to-Play Shows" Are even worse Than the already discredited Open Mic system". Jim Richardson's Organized Comedy. Retrieved 28 January 2019.

Some clubs require 10 bringers/show. If you show up with 9 people, you will not get on and your friends will not get their money back.

- ^ Durham, Rob (2011). Don't Wear Shorts on Stage: the stand-up guide to comedy. Middletown, DE. p. 63. ISBN 9781468004847.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bruce, Lenny (2016) [1965]. How to Talk Dirty & influence people: an autobiography. Philadelphia, PA: Da Capo. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-306-82529-3.

Comedy is an amorphous craft in the sense that there are no academies, there are no formulas. There are no books on comedy that can train an aspirant to command a salary of $200,000 a year, but it is a craft and it can be learned.

- ^ Guglielmi, Jodi (24 June 2013). "12 jobs comedians had before they were famous: Kevin Hart, Jon Stewart, Louis C.K. and more!". LaughSpin. LaughSpin. Archived from the original on 6 September 2013. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ Lintott, Sheila (2020). "Stand-up Comedy and Mental Health: Critiquing the Troubled Stand-Up Stereotype". In Oppliger, Patrice A.; Shouse, Eric (eds.). The Dark Side of Stand-up Comedy. United Kingdom: Springer Nature Switzerland AG: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 201–202. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-37214-9_10. ISBN 978-3-030-37213-2. S2CID 216475748.

[T]he concept of the 'professional' [stand-up comedian] is vague at best, making it quite difficult to say with any certainty whether a given comedian is professional. Should it be ... only those making their living primarily through stand-up comedy? Why not include stand-ups who earn their living otherwise, but regularly perform stand-up for supplementary income? Indeed, why not include stand-ups who make relatively little through stand-up, in some cases, nothing, but spend most of their evenings performing and their free-time writing stand-up? It’s overly simplistic to decide who counts as a stand-up comedian based on income, time devoted to writing or performing, number of performances, or talent.

- ^ Bergson, Henri (1900). Laughter: an Essay on the Meaning of the Comic. Translated by Brereton, Cloudesley; Rothwell, Fred. The Macmillan Company (published 1912).

the comic whose varieties might be calculated beforehand. This we shall call the professional comic

- ^ [92][93][94][95]

- ^ Lindsay Goldwert (18 April 2016). "Mark Normand: Funny for Money 002". SPENT (Podcast). Event occurs at 4:14-4:40.

I didn't start getting anywhere until ... five years in, financially ... even then, it was month to month [in New York City].

- ^ Buck, Jerry (9 December 1987). "Comedian has last laugh". Observer Reporter (AP TV Writer). Yakov Smirnoff. Retrieved 8 April 2019.

It took four or five years before I [Yakov Smirnoff] could make a living as a comedian.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ajaye, Franklyn (2002). Comic Insights: The Art of Stand-up Comedy. Jay Leno. Silman-James Press. pp. 124–125. ISBN 1-879505-54-1.

I've [Jay Leno] always told comedians that if you can do this for seven years, I mean physically make it to the stage for seven years, you'll always make a living ... You start to get paid at the end of the fourth or fifth year—I mean paid in terms of here's $500 dollars for one night, not $15 or $20 for a set.

- ^ Shydner, Ritch; Schiff, Mark, eds. (2006). "My Ride is Here: Ant". I Killed: True Stories of the Road From America's Top Comics. Ant (comedian) (First Paperback ed.). New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-307-38229-0. Archived from the original on 1 May 2012. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

Early in a comic's career, you get calls from ... bookers ... I would never again take a gig where it cost me more to get there than the pay, but back then I just needed stage time.

- ^ Koester, Megan (26 June 2014). "How to Be a Touring Stand-Up Comic". VICE. VICE MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

- ^ [97][98][99][100][101]

- ^ Durham, Rob (2011). Don't Wear Shorts on Stage: the stand-up guide to comedy. Middletown, DE. p. 12. ISBN 9781468004847.

The first paying position a comic can land is to emcee or host a show.

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (2018). The Politics of British Stand-Up Comedy: The New Alternative. Palgrave Studies in Comedy. London, UK: palgrave macmillan. p. 66. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01105-5. ISBN 978-3-030-01104-8. LCCN 2018956867.

Stand-up comedy is a solo art form in which the individualised voice of the performer is celebrated, it proffers a level of autonomy and creative freedom of which most workers are deprived and offers its most commercially successful proponents the opportunity to amass significant wealth.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Chris Dipetta. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 67. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

People like Leno and Wright can make ten thousand dollars a show now—that's not shocking. What's shocking is that I'm a virtually unknown comic and I make about one hundred twenty-five thousand dollars a year.

- ^ Seizer, Susan (2011). Stewart Huff. "On the Uses of Obscenity in Live Stand-Up Comedy". Anthropological Quarterly. The George Washington University Institute for Ethnographic Research. 84 (1): 212–213. doi:10.1353/anq.2011.0001. JSTOR 41237487. S2CID 144137009.

One of his main bookers nags him [the comedian] about losing the [foul] language, promising him so many more gigs ... and higher-paying ones at that, as these different kinds of gigs include corporate affairs, cruise ships, and Christian rallies.

- ^ Durham, Rob (2011). Don't Wear Shorts on Stage: the stand-up guide to comedy. Middletown, DE. p. 79. ISBN 9781468004847.

An emcee will make usually from $10-$35 a show. It's usually $25.

- ^ Ron White (2018). Ron White: If you Quit Listening, I'll Shut Up (Motion Picture). Event occurs at 39:21-39:41. Retrieved 29 March 2020.

I was the feature act at The Punchline Comedy Club in Sacramento, California. And ... traditionally in American comedy clubs, there's three acts: there's an opening act that makes between a hundred and two hundred [dollars] a week for nine shows, there's a feature act ... makes between four and five hundred bucks a week for nine shows, and a headliner, who can make absolutely anything depending on who they are.

- ^ Strauss, Duncan (3 November 1988). "Comedy: The Clubbing of America: The rise of comedy club chains". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

At the better chains, middle acts earn a weekly salary of $600 and up; headliners, anywhere from $2000 to $10,000, plus air fare and lodging – usually at the club's 'comedy condo' in town ... The chief variable is drawing power, based on accumulated TV and movie credits.

- ^ Hofstetter, Steve (2 July 2015). "What to Expect when You're Expecting ... to be Paid at a Club". Comedy Hints. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ^ O'Brien, Jane (21 October 2015). "No laughing matter: The secrets behind comedy success". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

If it's somebody starting off in the business it could be $1,500 a show. For somebody who's had some TV credits you could go from $4,500 to $7,500.

- ^ Durham, Rob (2011). Don't Wear Shorts on Stage: the stand-up guide to comedy. Middletown, DE. p. 87. ISBN 9781468004847.

the famous comics have what's called a "door deal" and get paid based on the amount of people in the crowd.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Rick Messina. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 68. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

It depends on the TV exposure of the comic, whether the comic draws and if he can command a higher ticket price.

- ^ Breidbart, Shaun Eli (2018-07-09). "13 Things a Stand-Up Comedian Won't Tell You". Reader's Digest. Trusted Media Brands, Inc. Retrieved 22 March 2019.

Those T-shirts and CDs we sell are what we make our real money on ... And when we do book a paying gig? We spend most of the money on transportation to get there.

- ^ Goldwert, Lindsay (16 October 2016). "Comedians explain the improbable economics of stand-up". QUARTZ. Quartz Media, Inc. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Zinoman, Jason; Megan, Angelo (2012-11-02). "Clever, How They Earn That Laugh". The New York Times. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ^ mattoo, Priyanka (22 September 2015). "What Comedy Pays". Vulture: Devouring Culture. NEW YORK MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ Simons, Seth (24 January 2018). "How Much Does Netflix Pay for 15 Minutes of Stand-Up?". PASTE. Retrieved 3 February 2019.

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (15 June 2018). "'I Sold the Same Special Twice!' How Netflix Is Driving an L.A. Comedy Gold Rush". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

Netflix is wooing superstar comics with eight-figure deals, including Dave Chappelle (a reported $60 million), Louis C.K. ($26 million), Amy Schumer ($20 million) and Jim Gaffigan ($10 million).

- ^ Bauer-Wolf, Jeremy (30 August 2018). "College Comedy: Provocative Yet ... PC?". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved 10 February 2019.

- ^ Golden, Fran (11 September 2014). "The best cruise lines for comedy". Great Falls Tribune. Retrieved 11 February 2019.

- ^ Holm, Heather (26 March 2009). "'Quick-witted' Burress set for laughs". Daily Eastern News: Tell the truth and don't be afraid. The Daily Eastern News. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

Hannibal Burress was the most popular comedian in Caponera's (2009) price range of $2,000.

- ^ Flanagan, Caitlin (September 2015). "That's Not Funny! Today's college students can't seem to take a joke". The Atlantic. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

Keith is one of the kings of the college circuit. A few years ago, he was the most-booked college comic, playing 120 campuses. He charges $2,300 for a single performance.

- ^ Leon, Harmon (1 July 2015). "God's Comics: Inside the World of Christian Stand-Up". VICE. VICE MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 18 February 2019.

Headliners can reap $1,500 to $2,500 per church comedy show

- ^ Abramovitch, Seth (15 June 2018). "'I Sold the Same Special Twice!' How Netflix Is Driving an L.A. Comedy Gold Rush". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

A newer comic on the national circuit can earn anywhere from $1,250 to $2,500 per week, according to one prominent touring agent; more established names can pull in anywhere from $10,000 to $100,000 in the same period.

- ^ Caffir, Justin (20 June 2018). "Comedians Reveal What the L.A. Stand-up Scene Actually Pays". Vulture: Devouring Culture. NEW YORK MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

it's very hard to make that amount even on the road ... To mislead someone with a figure that is beyond an exaggeration and just ridiculous.

- ^ Durham, Rob (2011). Don't Wear Shorts on Stage: the stand-up guide to comedy. Middletown, DE. p. 36. ISBN 9781468004847.

Bigger name comics have been known to pay thousands for jokes and hire writers ... After a famous comic has an HBO Special, they almost always hire writers to help them pump out more material.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Barry Sand. Simon & Schuster, Inc. pp. 239–240. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

Comics need material badly, especially once they get to be in demand—they've got to keep coming up with the stuff ... Often, once a comic becomes successful, his requirements for material begin to exceed his ability to create it—particularly in the case of TV spots, which 'eat' it instantly.

- ^ Hesse, Josiah (25 September 2014). "Should All Standup Comics Write Their Own Jokes?". Vulture: Devouring Culture. NEW YORK MEDIA LLC. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ Borns, Betsy (1987). Comic Lives: Inside the World of American Stand-up comedy. Rita Rudner. Simon & Schuster, Inc. p. 241. ISBN 0-671-62620-5.

[T]hat's another thing people do—write down jokes they see on TV, then sell them to other comics who don't realize what they're doing.

- ^ Kippola, Karl M. (August 2012). "Conclusion: Affirming White Masculinity by Deriding the Other". Acts of Manhood: The Performance of Masculinity on the American Stage, 1828-1865. Palgrave Studies in Theatre and Performance History. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 176–77. doi:10.1057/9781137068774. ISBN 978-1-349-34304-1.

Thomas D. Rice (1808-1860) originated the Jim Crow character, inspiring the minstrel show, which evolved into one of the most popular forms of variety entertainment through the end of the century and into the first distinctly American form of theatrical entertainment ... In the 1840s and 50s, the Virginia and Christy Minstrels built upon Rice’s success, formalizing a three-act structure of music and humor, variety entertainment, and scenes from plantation life (or burlesques of popular plays). Appealing across class lines, the minstrel show employed archetypal characters, created derogatory and fictitious pictures of African American males, and provided a lens through which whites viewed blacks ... Frederick Douglass described the purveyors of minstrel entertainment as 'filthy scum of white society, who have stolen from us a complexion denied to them by nature, in which to make money, and pander to the corrupt taste of their white fellow citizens.' Minstrelsy relied on the promise of presenting 'real' Southern life.

- ^ Parker, Bethany (12 September 2008). "Probing Question: What are the roots of stand-up comedy?". Research. PennState News. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 24 February 2019.

American stand-up comedy has its beginnings in the minstrel shows of the early 1800s

- ^ "Forms of Variety Theater". American Variety Stage: Vaudeville and Popular Entertainment: 1870-1920. Library of Congress (exhibit). Retrieved 24 January 2021.

[T]he minstrel show was the most popular form of public amusement in the United States from the 1840s through the 1870s. It virtually ended, in its original form, by 1896, although vestiges lasted well into the twentieth century. Much humor in later comedy forms originated in minstrelsy and adapted itself to new topics and circumstances. The minstrel show also provided American burlesque and other variety forms with a prototypical three-part format. The minstrel show began with a 'walk around' with a verbal exchange between the 'end' men and the interlocutor. An 'olio,' or variety section, followed. Finally, a one-act skit completed the show.

- ^ Oliar, Dotan; Sprigman, Christopher (2008). "There's No Free Laugh (Anymore): The Emergence of Intellectual Property Norms and the Transformation of Stand-Up Comedy". Virginia Law Review. 94 (8): 1843. JSTOR 25470605. Retrieved 16 September 2020.

Stand-up’s early roots can also be traced back to minstrel, a variety show format based in racial stereotypes which was widely performed in America between the 1840s and the 1940s. Minstrel acts would script dedicated ad-lib moments for direct actor-audience communication: these spots often were used for telling quick jokes.

- ^ Lee, Judith Yaross (2006). "Mark Twain as a Stand-up Comedian". The Mark Twain Annual. Penn State University Press. 4 (4): 5. JSTOR 41582220.

[Mark Twain] toured his first lecture, usually known as 'Our Fellow Savages of the Sandwich Islands,' for 100 performances beginning in 1866

- ^ Dudden, Arthur Power, ed. (1987). "The Importance of Mark Twain". American Humor. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 47–48. ISBN 0-19-504212-3.

[Mark Twain] is a reference figure for ... what we want to perceive to be the American character. As a public speaker and lecturer, indeed, the mature Mark Twain was very possibly our last performing humorist who presented himself as a 'general' personage—neither an easterner nor exactly a westerner, the embodiment ... of national regionalism, all parts equal, none predominating. This 'generic' persona, so different from Will Roger's lariat-twirling actor, is equally remote from the ethnic shtick of Woody Allen and Richard Pryor or the urban neurosis of Joan Rivers and David Brenner. He has no direct, obvious successors, only his impersonators; the humor of our contemporary nightclubs is fragmented and typecast. The foe of humbug, explicitly rebelling against outworn Romantic forms and themes, he detested high airs and smug complacency—putting him in the progression that has led to the stand-up insults of W.C. Fields as well as Lenny Bruce ... Among other feats, he contrived his public persona so as to convey the impression of (feigned) laziness, lack of erudition, easy success ... Mark Twain endures because he is greater than any of his possible classifications—crackerbarrel philosopher, literary comedian ... vernacular humorist, after-dinner speaker

- ^ Zoglin, Richard. "Stand-up comedy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved 8 March 2019.

- ^ "Forms of Variety Theater". American Variety Stage: Vaudeville and Popular Entertainment: 1870-1920. Library of Congress (exhibit). Retrieved 24 January 2021.

The popular burlesque show of the 1870s though the 1920s referred to a raucous, somewhat bawdy style of variety theater. It was inspired by Lydia Thompson and her troupe, the British Blondes, who first appeared in the United States in the 1860s, and also by early 'leg' shows such as 'The Black Crook' (1866). Its form, humor, and aesthetic traditions were largely derived from the minstrel show. One of the first burlesque troupes was the Rentz-Santley Novelty and Burlesque Company, created in 1870 by M.B. Leavitt, who had earlier feminized the minstrel show with her group Madame Rentz's Female Minstrels. Burlesque rapidly adapted the minstrel show's tripartite structure: part one was composed of songs and dances rendered by a female company, interspersed with low comedy from male comedians. Part two was an 'olio' of short specialties in which the women did not appear. The show's finish was a grand finale. The popular burlesque show of this period eventually evolved into the strip tease which became the dominant ingredient of burlesque by the 1930s.

- ^ Page, Brett (March 2004) [1915]. Writing for Vaudeville (10 ed.). Project Gutenberg.

The pure vaudeville monologue, which was defined as a humorous talk spoken by one person, possesses unity of character, is not combined with any other entertainment form, is marked by compression [word economy], follows a definite form of construction, and usually requires from ten to fifteen minutes for delivery. Humor is its most notable characteristic; unity of the character delivering it, or of its 'hero,' is its second most important requirement. Each point, or gag, is so compressed that to take away or add even one word would spoil its effect; each is expressed so vividly that the action seems to take place before the eyes of the audience. Finally, every point leads out of the preceding point so naturally, and blends into the following point so inevitably, that the entire monologue is a smooth and perfect whole.

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (November 2011). "Containing the Audience: The 'Room' in Stand-Up Comedy" (PDF). University of Kent, UK. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies. 8 (2): 220. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

The term 'room' means more than just the physical space in which the performance takes place; it is the term used to summarise a combination of factors which include the nature of the space, the way that space is set up, the character of the audience and more.

- ^ Brodie, Ian (2014). "Stand-Up Comedy and a Folkloristic Approach". A Vulgar Art: A New Approach to Stand-up Comedy. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-62846-182-4.

All writers on stand-up comedy, without exception, specifically emphasize that a stand-up comedian is on a stage talking with an audience. Stand-up comedy is neither a series of narratives nor a series of jokes: it is a form of small talk

- ^ Ricny, Benedikt (2014). A Look behind the Curtains of Stand-Up Comedy: Psychology in Stand-Up Comedy (PDF) (PhD). Palacký University Olomouc. Retrieved 29 December 2020.

- ^ Lefebvre, Henri (2002) [1974]. The Production of Space. Translated by Nicholson-Smith, Donald. Blackwell Publishing. p. 288. ISBN 0-631-18177-6.

For, while abstract space remains an arena of practical action, it is also an ensemble of images, signs and symbols. It is unlimited, because it is empty, yet at the same time it is full of juxtapositions, of proximities ('proxemics'), of emotional distances and limits. ... the same abstract space may serve profit

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Merrifield, Andrew (26 June 1993). "Place and Space: A Lefebvrian Reconciliation". Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers). 18 (4): 516–531. doi:10.2307/622564. ISSN 0020-2754. JSTOR 622564. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

[S]ocial space becomes a force of production itself (Lefebvre, 1979; Harvey, 1982; Swyngedouw, 1991, 1992), representing simultaneously a network of exchange and a flow of commodities, communication, energy and resources.

- ^ Fox, Jesse David (11 May 2021). "Who Should John Mulaney Be Now?". Vulture: Devouring Culture. Retrieved 12 May 2021.

Stand-ups need the audience to know what's funny, what's interesting, what they think. In exchange for their vulnerability, they get connection.

- ^ [140][141][142][143][144][145]

- ^ Lindfors, Antti (6 May 2019). "Cultivating Participation and the Varieties of Reflexivity in Stand-Up Comedy". University of Turku, Finland. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology. 29 (3): 283. doi:10.1111/jola.12223. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

In the heat of real-time performance ... comics can 'read the room' through jokes that are optimal for gauging their interlocutors' intellectual, moral, emotional, or other boundaries and preferences, e.g., through lowbrow, strategically ambiguous, or perhaps seemingly offensive bits.

- ^ Lefebvre, Henri (2002) [1974]. The Production of Space. Translated by Nicholson-Smith, Donald. Blackwell Publishing. p. 142. ISBN 0-631-18177-6.

Semiology is also the source of the claim that space is susceptible of a 'reading,' and hence the legitimate object of a practice (reading/writing). The space of the city is said to embody a discourse, a language.

- ^ Maran, Timo; Kull, Kalevi (2014). "Ecosemiotics: Main Principles and Current Developments". Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 96 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1111/geob.12035. JSTOR 43299746. S2CID 145068550. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

The consideration of geographic space or landscape as a text (Duncan 1992; Spirn 1998) is also an instance of semiotic approach.

- ^ Sebeok, Thomas A. (2001). Signs: An Introduction to Semiotics (PDF) (2 ed.). Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press Incorporated. p. 7. ISBN 0-8020-8472-9.

Messages can be constructed on the basis of single signs or, more often than not, as combinations of them. The latter are known as texts. A text constitutes, in effect, a specific 'weaving together' of signs in order to communicate something. The signs that go into the make-up of texts belong to specific codes.

- ^ Morais, Robert J. (2007). "Conflict and Confluence in Advertising Meetings". Human Organization. Society for Applied Anthropology. 66 (2): 150–159. doi:10.17730/humo.66.2.p480687204l735h5. ISSN 0018-7259. JSTOR 44127108. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

'Read the room.' His meaning: assess client reactions as ideas are presented and adjust ... They scan faces for confusion, comprehension, and delight. They study eyes and body language. ... The process of reading the room is like comprehending the difference between a wink and a blink (Geertz 1973:6-7). It requires contextual understanding: knowing the psychology of the participants, the strength of the creative work

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bouissac, Paul (2015). The Semiotics of Clowns and Clowning: Rituals of Transgression and the Theory of Laughter. Bloomsbury Advances in Semiotics. NY: Bloomsbury. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4725-2173-6.

From a semiotic perspective—that is, the investigation of its meaning-making potential—the human face has been equated with a display board upon which interacting individuals can read and interpret each others' moods and intentions.

- ^ [147][148][149][150][151][152]

- ^ Dore, Margherita (January 2018). "Laughing at you or laughing with you? Humor negotiation in intercultural stand-up comedy" (PDF). Sapienza University of Rome. John Benjamins Publishing Company: 2. Retrieved 13 March 2021.

Comedians start their routines by 'working the room' and asking the audience rapid-fire questions (which can result in insults or quick punch lines) to verify whether both parties share the same values, thus contributing to setting the mood of the show (Mintz, 1985: 78–79)

- ^ Wiley, Norbert (1994). The Semiotic Self. The University of Chicago Press. pp. 160, 161. ISBN 0-226-89816-4.

All signs have points of view built into them. ...As I mentioned in chapter 4, the interpretant is responding to and reflexive of the sign.

- ^ Maran, Timo; Kull, Kalevi (2014). "Ecosemiotics: Main Principles and Current Developments". Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography. 96 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1111/geob.12035. JSTOR 43299746. S2CID 145068550. Retrieved 5 May 2021.

Semiotic construction makes (re-designs) the artefacts surrounding the organism. This means that sign processes not only permanently re-design our concepts but they also, and simultaneously, redesign our surrounding matter.

- ^ Marc Maron (13 April 2021). "Doug Stanhope / Janeane Garofalo". WTF with Marc Maron (Podcast). Retrieved 13 April 2021.

- ^ Gillota, David (2019). "Reckless Talk: Exploration and Contradiction in Dave Chappelle's Recent Stand-Up Comedy". Studies in Popular Culture. Popular Culture Association in the South. 42 (1): 1–22. JSTOR 26926330. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

In his refusal to 'feel bad' about what he says on stage, Chappelle suggests that his first responsibility is to his craft. He acknowledges, however, that such a responsibility may end up creating discomfort for audience members and himself. ... Chappelle suggests that offended audience members should also blame themselves because they have 'got to remember' that he is only saying these things because they are [audience-tested] funny.

- ^ Quirk, Sophie (November 2011). "Containing the Audience: The 'Room' in Stand-Up Comedy" (PDF). University of Kent, UK. Participations: Journal of Audience & Reception Studies. 8 (2): 236. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

A good room can implicitly invite the 'right kind' of audience, and tell that audience how to behave and how to respond to the comedian's material. It can orchestrate the physical arrangement of the audience within the space, such that the performer is faced with minimal competition for audience attention. It can work on the audience's confidence, allowing each audience member to feel part of a homogenised group and creating acoustics which allow each laugh to fuel the next. The room can also send the message that the event is exciting; a success of which the audience are part. A good gig is not founded on the hope that a comedian can battle through any circumstance, but is rather a matter of creating, proactively, that fine balance between numerous factors which will allow for the best possible interaction.

- ^ Petty, Margaret Maile (2012). "Curtains and the Soft Architecture of the American Postwar Domestic Environment" (PDF). Home Cultures. 9 (1): 35–56. doi:10.2752/175174212X13202276383779. S2CID 114998722. Retrieved 16 May 2021.

[L]ighting techniques could also have a 'psychological effect,' creating 'reassuring' and 'less formal' spaces—characteristics typically expected of the domestic environment. Color choice, Kelly advised, also affected the mood or psychological conditions of the interior.

- ^ Schielke, Thomas (2019). "The Language of Lighting: Applying Semiotics in the Evaluation of Lighting Design". LEUKOS. 15 (2–3): 227–248. doi:10.1080/15502724.2018.1518715. ISSN 1550-2724.

Semiotics became useful for analyzing stage lighting and the communication between the performer and the audience and to identify lighting signs associated with productions (Moran 2007).

- ^ Thomas, James M. (2015). "Laugh through it: Assembling difference in an American stand-up comedy club". Ethnography. Sage Publications, Inc. 16 (2): 166–186. doi:10.1177/1466138114534336. JSTOR 26359086. S2CID 144390090. Retrieved 4 May 2021.

Deleuze and Guattari’s ontology of a book is useful for framing the relationship of other cultural forms to their exterior conditions. Arguing that '[t]here is no longer a tripartite division between a field of reality [e.g. social world], a field of representation [e.g. the performance], and a field of subjectivity [e.g. the individual comic]' (Deleuze and Guattari, 1987:23), the concept of assemblage is meant to demonstrate empirically [connections, viz., social world, the performance, and the individual comic].

- ^ [159][160][161][162]

- ^ Jump up to: a b Antoine, Katja (2016). "'Pushing the Edge' of Race and Gender Hegemonies through Stand-up Comedy: Performing Slavery as Anti-racist Critique". Etnofoor. Stichting Etnofoor. 28 (1): 41. JSTOR 43823941. Retrieved 15 September 2020.

The first comic on stage carries the burden of 'building the energy in the room'. The comedians who follow in the line-up have to sustain it. Should someone fail at doing this and leave the audience 'cold', the next comic has to 'bring the energy back up' ... Ideally [the comedians] arrive at a venue when the show starts in order to 'read' the audience. Reading the audience is a visual practice (What are the demographics?[)]…and an affective practice (How are they responding to the comic on stage?[)]…At the very least, comics will show up a few acts ahead of their own for that purpose. They have to know the energy of the room in order to work the crowd right.