Stanford prison experiment

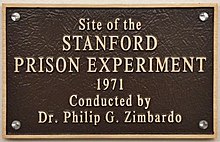

The Stanford prison experiment (SPE) was a role-play and simulation, held at Stanford University in summer 1971. It was intended to examine the effects of situational variables on participants' reactions and behaviors, in a two-week simulation of a prison environment. Stanford psychology professor Philip Zimbardo led the research team who conducted the experiment.[1]

The controversial experiment gained a large amount of publicity over the ensuing decades. However, the experiment's scientific validity has now been discredited[2][3] and its methods described as "deeply flawed",[4] and "a lie".[5] The experiment was described in many introductory social psychology textbooks,[6] although some exclude it due to concerns about its methodology and ethics.[7] In 2019, the American Psychological Association advised of "the need for teachers and textbook authors to both revise and repurpose the coverage of the SPE in their classes and textbooks, respectively".[8] The experiment's findings have been called into question, and the experiment has been criticized for unscientific methodology.[9] The day before the experiment began, Zimbardo's team coached the "guards" about their roles and what was (and was not) acceptable for them to do to "prisoners." One recurring criticism of the SPE is that participants were biased in their behavior based on demand characteristics.

The US Office of Naval Research funded the experiment as an investigation into behavior. Certain portions of it were filmed, and excerpts of footage are publicly available.[10]

The first official day of the experiment was August 15, 1971. The experiment began with prisoners being arrested in their own neighborhoods by real Palo Alto police. Some guards exhibited abusive behavior toward prisoners, which led Zimbardo, at the urging of Christina Maslach, to stop the experiment before it was due to conclude. The study was cancelled six days later on August 20. After debriefing with his "guards" and "prisoners", Zimbardo analyzed the data and published his findings.[11][12]

While SPE cannot ethically be replicated, actual prisons can see even more intense abuse and conflict between guards. On August 21, 1971, the day after SPE ended, six people died in an escape attempt and prison riot inside San Quentin State Prison.

Zimbardo's goals[]

The official website of the Stanford Prison Experiment describes the experiment goal as follows:

We wanted to see what the psychological effects were of becoming a prisoner or prison guard. To do this, we decided to set up a simulated prison and then carefully note the effects of this institution on the behavior of all those within its walls.[13]

A 1997 article from the Stanford News Service described the experiment goal in a more detailed way:

Zimbardo's primary reason for conducting the experiment was to focus on the power of roles, rules, symbols, group identity and situational validation of behavior that generally would repulse ordinary individuals. "I had been conducting research for some years on deindividuation, vandalism and dehumanization that illustrated the ease with which ordinary people could be led to engage in anti-social acts by putting them in situations where they felt anonymous, or they could perceive of others in ways that made them less than human, as enemies or objects," Zimbardo told the Toronto symposium in the summer of 1996.[14]

The study was funded by the US Office of Naval Research to understand anti-social behaviour.[15] The United States Navy and the United States Marine Corps wanted to investigate conflict between military guards and prisoners.[16]

The experiment[]

Recruitment[]

After receiving approval from the university to conduct the experiment, study participants were recruited using an ad in the "help wanted" section of the Palo Alto Times and The Stanford Daily newspapers in August 1971:

Male college students needed for psychological study of prison life. $15 per day for 1–2 weeks, beginning Aug. 14. For further information and applications, come to room 248 Jordan Hall, Stanford University.

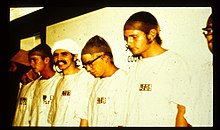

75 men applied, and after screening assessments and interviews, 24 were selected to participate in a two-week prison simulation. The applicants were predominantly white, middle-class, and appeared to be psychologically stable and healthy. The group of subjects was intentionally selected to exclude those with criminal backgrounds, psychological impairments, or medical problems. On a random basis, half of the subjects were assigned the role of "guard (nine plus three potential substitutes)," and half were assigned to the role of prisoner (also nine plus three potential substitutes). They all agreed to participate for a 7- to 14-day period for $15 per day (roughly equivalent to $101 in 2021).[17]

The day before the experiment officially began, the participants playing "guards" were given uniforms and equipment, specifically chosen to mimic the de-individuating uniforms professional prison guards and military often wear.

The experiment was conducted in a 35-foot (10.5 m) section of the basement of Jordan Hall, Stanford's psychology building. The prison had two fabricated walls: one at the entrance, and one at the cell wall to block observation. Each cell (6 × 9 feet, or 1.8 × 2.7 m) had room enough for three, a cot (with mattress, sheet, and pillow) for each prisoner, and was unlit.[18] Prisoners were confined 24 hours a day. In contrast, the guards lived in a different environment, separate from the prisoners. The guards were given access to special areas for rest and relaxation.

Zimbardo took on the role of the Superintendent and an undergraduate research assistant, David Jaffee, took on the role of the Warden.[11]

Day 0: setup[]

Saturday, August 14

The researchers held an orientation session for the guards the day before the experiment began, during which "guards" were instructed not to harm the prisoners physically or withhold food or drink, but to maintain law and order. The researchers provided the guards with wooden batons to establish their "status", clothing similar to that of an actual prison guard (khaki shirt and pants from a local military surplus store), and mirrored sunglasses to prevent eye contact and create anonymity.

The small mock prison cells were set up to hold three prisoners each. There was a small corridor for the prison yard, a closet for solitary confinement, and a bigger room across from the prisoners for the guards and warden. The prisoners were to stay in their cells and the yard all day and night until the end of the study. The guards were told to work in teams of three for eight-hour shifts. The guards were not required to stay on-site after their shift.[11]: 1–2

Day 1: arrests[]

Sunday, August 15

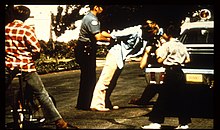

The prisoners were "arrested" at their homes or assigned sites, "charged" with armed robbery, and burglary, Penal Codes 211, and 459. The local Palo Alto police department assisted Zimbardo's team with the simulated arrests and conducted full booking procedures on the prisoners at the Palo Alto City police headquarters, which included warning of Miranda rights, fingerprinting and taking mug shots. All of these actions were video-documented by a local San Francisco TV station reporter travelling around in Zimbardo’s car. Meanwhile, three guards prepped for the arrival of the inmates. The prisoners were then transported to the mock prison from the police station, sirens wailing. In the Stanford County Jail they were systematically strip searched, given their new identities (Inmate identification number), and uniform. Prisoners wore uncomfortable, ill-fitting smocks and stocking caps, as well as a chain around one ankle. Guards were instructed to call prisoners by their assigned numbers, sewn on their uniforms, instead of by name, thereby dehumanizing prisoners. The prisoners were then greeted by the warden, who conveyed the seriousness of their offense and their new status as prisoners. With the rules of the prison presented to them, the inmates retired to their cells for the rest of the first day of the experiment.[11]: 2–5

Day 2: prisoners rebel[]

Monday, August 16

Guards referred to prisoners by their identification and confined them to their small cells. At 2:30 am the prisoners rebelled against guards’ wake up calls of whistles and clanging of batons. Prisoners refused to leave their cells to eat in the yard, ripped off their inmate number tags, took off their stocking caps and insulted the guards.

In response, guards sprayed fire extinguishers at the prisoners to reassert control. The three back-up guards were called in to help regain control of the prison. Guards removed all of the prisoners’ clothes, removed mattresses and sentenced the main instigators time in The Hole. They attempted to dissuade any further rebellion using psychological warfare. One of the guards said to the other that, “these are dangerous prisoners.”[11]: 5–8

Day 3: guards strike back[]

Tuesday, August 17

In order to restrict further acts of disobedience, the guards separated and rewarded prisoners who had minor roles in the rebellion. The three spent time in the "good" cell where they received clothing, beds, and food denied to the rest of the jail population. After an estimated 12 hours, the three returned to their old cells that lacked beds.

Guards abused their power to humiliate the inmates. They had the prisoners count off and do pushups arbitrarily, restricted access to the bathrooms, and forced them to relieve themselves in a bucket in their cells.

Prisoner #8612 began to show signs of a mental breakdown, he began screaming in rage. Upon seeing his suffering, research assistant Craig Haney immediately released #8612.[11]: 8–11

Day 4: prisoners divided[]

Wednesday, August 18

Witnessing that guards divide prisoners based on their good or rebellious behavior, the inmates started to distance themselves from one another. Rioters believed that other prisoners were snitches and vice versa. Other prisoners saw the rebels as a threat to the status quo since they wanted to have their sleeping cots and clothes again.

Prisoner #819 began showing symptoms of distress: he began crying in his cell. A priest was brought in to speak with him, but #819 declined to talk and instead asked for a medical doctor. After hearing him cry, Zimbardo reassured him of his actual identity and removed the prisoner. When #819 was leaving, the guards cajoled the remaining inmates to loudly and repeatedly decry that "#819 is a bad prisoner."[11]: 11–12

Day 5: growing concerns[]

Thursday, August 19

The day was scheduled for visitations by friends and family of the inmates in order to simulate the prison experience.

Zimbardo and the guards made visitors wait for long periods of time to see their loved ones. Only two visitors could see any one prisoner and only for just ten minutes while a guard watched. Parents grew concerned about their sons' wellbeing and whether they had enough to eat. Some parents left with plans to contact lawyers to gain early release of their ward.

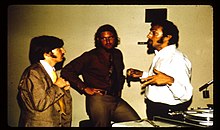

On the same day, Zimbardo's colleague Gordon H. Bower arrived to check on the experiment and questioned Zimbardo about the independent variable in play. Furthermore, Christina Maslach visited the prison that night, and was distressed by observing the guards abusing the prisoners, forcing them to wear bags over their heads. She challenged Zimbardo about his lack of caring oversight, and the immorality of the study. Finally, she made evident that Zimbardo had been changed by his role as Superintendent into someone she did not recognize and did not like. Her direct challenges prompt Zimbardo to end the SPE the next day.[11]: 13–16

Day 6: study canceled[]

Friday, August 20

Due to Maslach's outrage, the parents' concerns, and the increasing brutality exhibited by guards in the experiment, Zimbardo ended the study on Day 6. Zimbardo gathered the participants (guards, prisoners, and researchers) to let them know that the experiment was over, and arranged to pay them the full fee for 14 days, $210 (equivalent to $1435 in 2021). Zimbardo then met for several hours of informed debriefing first with all of the prisoners, then the guards, and finally everyone came together to share their experiences. Next, all participants were asked to complete a personal retrospective to be mailed to him subsequently. Finally, all participants were invited to return a week later to share their opinions and emotions.

Later, the physical components of the Stanford County Jail were taken down and out of the basement of Jordan Hall as the cells returned to their usual function as grad student offices. Zimbardo and his graduate student research team, Craig Haney and Curtis Banks, began compiling the multiple sources of data that would be the basis for several articles they soon wrote about their experiment, and for Zimbardo's later expanded and detailed review of the SPE in The Lucifer Effect (2007).[11]: 16–17 [19]

Conclusions[]

According to Zimbardo's interpretation of the SPE, it demonstrated that the simulated-prison situation, rather than individual personality traits, caused the participants' behavior. Using this situational attribution, the results are compatible with those of the Milgram experiment, where random participants complied with orders to administer seemingly dangerous and potentially lethal electric shocks to a shill.[20]

The experiment has also been used to illustrate cognitive dissonance theory and the power of authority.[21]

Participants' behavior may have been shaped by knowing that they were watched (Hawthorne effect).[22] Instead of being restrained by fear of an observer, guards may have behaved more aggressively when supervisors observing them did not step in to restrain them.[20]

Zimbardo instructed the guards before the experiment to disrespect the prisoners in various ways. For example, they had to refer to prisoners by number rather than by name. This, according to Zimbardo, was intended to diminish the prisoners' individuality.[23] With no control, prisoners learned they had little effect on what happened to them, ultimately causing them to stop responding and give up.[24]

One positive result of the study is that it has altered the way US prisons are run. For example, juveniles accused of federal crimes are no longer housed before trial with adult prisoners, due to the risk of violence against them.[22]

Shortly after the study was completed, there were bloody revolts at both the San Quentin and Attica prison facilities, and Zimbardo reported his findings on the experiment to the US House Committee on the Judiciary.[25]

Criticism and response[]

There has been controversy over both the ethics and scientific rigor of the Stanford prison experiment since nearly the beginning, and it has never been successfully replicated.[26]

Some of the guards' behavior allegedly led to dangerous and psychologically damaging situations.[27] Ethical concerns surrounding the experiment often draw comparisons to the similarly controversial experiment by Stanley Milgram, conducted ten years earlier in 1961 at Yale University when he studied obedience to authority.[20] With the treatment that the guards were giving to the prisoners, the guards would become so deeply absorbed into their role as a guard that they would emotionally, physically and mentally humiliate the prisoners:

"Each prisoner was systematically searched and stripped naked. He was then deloused with a spray, to convey our belief that he may have germs or lice[...] Real male prisoners don't wear dresses, but real male prisoners do feel humiliated and do feel emasculated. Our goal was to produce similar effects quickly by putting men in a dress without any underclothes. Indeed, as soon as some of our prisoners were put in these uniforms they began to walk and to sit differently, and to hold themselves differently – more like a woman than like a man."[28]

Conclusions and observations drawn by the experimenters were largely subjective and anecdotal, and the experiment is practically impossible for other researchers to accurately reproduce. Erich Fromm claimed to see generalizations in the experiment's results and argued that the personality of an individual does affect behavior when imprisoned. This ran counter to the study's conclusion that the prison situation itself controls the individual's behavior. Fromm also argued that the amount of sadism in the "normal" subjects could not be determined with the methods employed to screen them.[29]

In 2018, digitized recordings available on the official SPE website were widely discussed, particularly one where "prison warden" David Jaffe tried to influence the behavior of one of the "guards" by encouraging him to "participate" more and be more "tough" for the benefit of the experiment.[30] The study was criticized in 2013 for demand characteristics by psychologist Peter Gray, who argued that participants in psychological experiments are more likely to do what they believe the researchers want them to do, and specifically in the case of the Stanford prison experiment, "to act out their stereotyped views of what prisoners and guards do."[31] Other critics have argued that selection bias may have played a role in the results due to the ad describing a need for prisoners and guards rather than a social psychology study.[32]

Ethical issues[]

The experiment was perceived by many to involve questionable ethics, the most serious concern being that it was continued even after participants expressed their desire to withdraw. Despite the fact that participants were told they had the right to leave at any time, Zimbardo did not allow this.[22]

Since the time of the Stanford prison experiment, ethical guidelines have been established for experiments involving human subjects.[33][34][35] The Stanford prison experiment led to the implementation of rules to preclude any harmful treatment of participants. Before they are implemented, human studies must now be reviewed and found by an institutional review board (US) or ethics committee (UK) to be in accordance with ethical guidelines set by the American Psychological Association (US) or British Psychological Society (UK).[22] These guidelines involve the consideration of whether the potential benefit to science outweighs the possible risk for physical and psychological harm.

A post-experimental debriefing is now considered an important ethical consideration to ensure that participants are not harmed in any way by their experience in an experiment. Though Zimbardo did conduct debriefing sessions, they were several years after the Stanford prison experiment. By that time, numerous details were forgotten; nonetheless, many participants reported that they experienced no lasting negative effects.[22] Current standards specify that the debriefing process should occur as soon as possible to assess what psychological harm, if any, may have been done and to rehabilitate participants, if necessary. If there is an unavoidable delay in debriefing, the researcher is obligated to take steps to minimize harm.[36]

Comparisons to Abu Ghraib[]

When acts of prisoner torture and abuse at the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq were publicized in March 2004, Zimbardo himself, who paid close attention to the details of the story, was struck by the similarity with his own experiment. He was dismayed by official military and government representatives' shifting the blame for the torture and abuses in the Abu Ghraib American military prison onto "a few bad apples", rather than acknowledging the possibly systemic problems of a formally established military incarceration system.[citation needed]

Eventually, Zimbardo became involved with the defense team of lawyers representing one of the Abu Ghraib prison guards, Staff Sergeant Ivan "Chip" Frederick. Zimbardo was granted full access to all investigation and background reports, and testified as an expert witness in Frederick's court martial, which resulted in an eight-year prison sentence for Frederick in 2004.[37]

Zimbardo drew from his participation in the Frederick case to write the book The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil, which deals with the similarities between his own Stanford prison experiment and the Abu Ghraib abuses.[19]

Similar studies[]

BBC prison study

Psychologists Alex Haslam and Steve Reicher conducted the BBC Prison Study in 2002 and published the results in 2006.[38] This was a partial replication of the Stanford prison experiment conducted with the assistance of the BBC, which broadcast events in the study in a documentary series called The Experiment. Their results and conclusions differed from Zimbardo's and led to a number of publications on tyranny, stress, and leadership. The results were published in leading academic journals such as British Journal of Social Psychology, Journal of Applied Psychology, Social Psychology Quarterly, and Personality and Social Psychology Review. The BBC Prison Study is now taught as a core study on the UK A-level Psychology OCR syllabus.

While Haslam and Reicher's procedure was not a direct replication of Zimbardo's, their study casts further doubt on the generality of his conclusions. Specifically, it questions the notion that people slip mindlessly into roles and the idea that the dynamics of evil are in any way banal. Their research also points to the importance of leadership in the emergence of tyranny of the form displayed by Zimbardo when briefing guards in the Stanford experiment.[39][40]

Experiments in the United States

In 1967, The Third Wave experiment involved the use of authoritarian dynamics similar to Nazi Party methods of mass control in a classroom setting by high school teacher Ron Jones in Palo Alto, California with the goal of vividly demonstrating to the class how the German public in World War II could have acted in the way it did.[41] Although the veracity of Jones' accounts has been questioned, several participants in the study have gone on record to confirm the events.[42]

In both experiments, participants found it difficult to leave the study due to the roles they were assigned. Both studies examine human nature and the effects of authority. Personalities of the subjects had little influence on both experiments despite the test before the prison experiment.[43]

In both the Milgram and the Zimbardo studies, participants conform to social pressures. Conformity is strengthened by allowing some participants to feel more or less powerful than others. In both experiments, behavior is altered to match the group stereotype.

In popular culture[]

Italian filmmaker Carlo Tuzii was the first director to film a story based on the experiment when, in 1977, he directed the television film La gabbia («The cage»), for Rai 1. Tuzii's original story called for a group of twenty young people from various social backgrounds, who were randomly divided into "guards" and "prisoners" and instructed to spend one month on opposite sides of an enormously high gate, with barbed wire on top, build in the middle of a large park. Before principal photography started, however, some concerns from RAI executives forced Tuzii and the screenwiters to alter the script into a very similar story to the actual Stanford experiment, including the outcome. Miguel Bosé starred as lead "prisoner" Carlo; progressive pop band Pooh scored the film and had a hit in Italy with a 7-inch edit of the theme tune.

The 2001 film Das Experiment starring Moritz Bleibtreu is based on the experiment. It was remade in 2010 as The Experiment.[44][45]

The 2015 film The Stanford Prison Experiment is based on the experiment.[46]

The YouTube series Mind Field, hosted by Michael Stevens, features an episode discussing the experiment.[47]

In Season 3, Episode 2 of the television series Veronica Mars, entitled "My Big Fat Greek Wedding", a similar experiment is featured.[48]

In The Overstory by Richard Powers, the fictional character Douglas Pavlicek is a prisoner in the experiment, an experience which shapes later decisions.[49]

In Season 15, Episode 10 of television show American Dad, "American Data", Roger recruits Steve, Toshi, Snot and Barry into a similar experiment.[50]

See also[]

- Person-situation debate

- Trier social stress test

- Unethical human experimentation in the United States

- Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil

- Milgram experiment

- The Third Wave (experiment)

- Project MKUltra

- Rhythm 0

Footnotes[]

- ^ Bekiempis, Victoria (August 4, 2015). "What Philip Zimbardo and the Stanford Prison Experiment Tell Us About Abuse of Power". Newsweek.

- ^ Le Texier, Thibault (October 2019). "Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment". American Psychologist. 74 (7): 823–839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 31380664. S2CID 199437070.

- ^ "Time to change the story | The Psychologist". thepsychologist.bps.org.uk. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Geggel, Laura (June 15, 2018). "One of Psychology's Most Famous Experiments Was Deeply Flawed". livescience.com. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Blum, Ben (September 6, 2019). "The Lifespan of a Lie". GEN. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ "Intro to psychology textbooks gloss over criticisms of Zimbardo's Stanford Prison Experiment". September 7, 2014.

- ^ "Psychology Itself Is Under Scrutiny".

- ^ "APA PsycNet". doi.apa.org: 298–304. doi:10.1037/stl0000163. S2CID 203052521. Retrieved October 11, 2021.

- ^ Le Texier, Thibault (August 5, 2019). "Debunking the Stanford Prison Experiment". American Psychologist. 74 (7): 823–839. doi:10.1037/amp0000401. ISSN 1935-990X. PMID 31380664. S2CID 199437070.

- ^ "FAQ on official site". Archived from the original on September 9, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "A Simulation Study of the Psychology of Imprisonment" (PDF). Stanford University. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "8. Conclusion". Stanford Prison Experiment. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Slideshow on official site". Prisonexp.org. p. Slide 4. Archived from the original on May 12, 2000.

- ^ "The Stanford Prison Experiment: Still powerful after all these years (1/97)". News.stanford.edu. August 12, 1996. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

In the prison-conscious autumn of 1971, when George Jackson was killed at San Quentin and Attica erupted in even more deadly rebellion and retribution, the Stanford Prison Experiment made news in a big way. It offered the world a videotaped demonstration of how ordinary people, middle-class college students, can do things they would have never believed they were capable of doing. It seemed to say, as Hannah Arendt said of Adolf Eichmann, that normal people can take ghastly actions.

- ^ "More Information". Stanford Prison Experiment. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "The Stanford Prison Experiment | Psychology Today". www.psychologytoday.com. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Haney, C.; Banks, W. C.; Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). "Interpersonal dynamics in a simulated prison". International Journal of Criminology and Penology. 1: 69–97.

- ^ "Index of /downloads". zimbardo.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ a b "The Lucifer Effect". lucifereffect.com.

- ^ a b c Konnikova, Konnikova (June 12, 2015). "The Real Lesson of the Stanford Prison Experiment". New Yorker. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

Occasionally, disputes between prisoner and guards got out of hand, violating an explicit injunction against physical force that both prisoners and guards had read prior to enrolling in the study. When the "superintendent" and "warden" overlooked these incidents, the message to the guards was clear: all is well; keep going as you are. The participants knew that an audience was watching, and so a lack of feedback could be read as tacit approval. And the sense of being watched may also have encouraged them to perform.

- ^ "What Is The Cognitive Dissonance Theory Of The Stanford... | ipl.org". www.ipl.org. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Zimbardo – Stanford Prison Experiment | Simply Psychology". www.simplypsychology.org. Retrieved November 11, 2015.|quote=Zimbardo (1973) was interested in finding out whether the brutality reported among guards in American prisons was due to the sadistic personalities of the guards (i.e., dispositional) or had more to do with the prison environment (i.e., situational).

- ^ Zimbardo (2007), The Lucifer Effect , p.54.

- ^ "Index of /downloads". zimbardo.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2015.

- ^ No. 3, United States Congress House Committee on the Judiciary Subcommittee (1971). Corrections: Hearings Before Subcommittee No. 3 of the Committee on the Judiciary, House of Representatives, Ninety-second Congress, First [and Second] Session on Corrections. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ^ Blum, Ben. "The Lifespan of a Lie – Trust Issues". Medium. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ "Conclusion". Stanford Prison Experiment.

- ^ "3. Arrival". Stanford Prison Experiment. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ "1971: Philip Zimbardo, Stanford Prison Experiment – precursor for Abu Ghraib torture. – AHRP". AHRP. December 28, 2014. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ Masterson, Andrew (July 9, 2018). "New evidence shows Stanford Prison Experiment conclusions "untenable"". Cosmos. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

Archival recordings show one of the world's most famous psychology experiments was poorly designed – and its use to justify brutality baseless.

- ^ Gray, Peter (2013). "Why Zimbardo's Prison Experiment Isn't in My Textbook". Freedom to Learn blog.

- ^ Carnahan, Thomas; McFarland, Sam (2007). "Revisiting the Stanford prison experiment: could participant self-selection have led to the cruelty?" (PDF). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 33 (5): 603–14. doi:10.1177/0146167206292689. PMID 17440210. S2CID 15946975.

- ^ US Department of Health & Human Services Code of Federal Regulations, Title 45, Part 46, Protection of Human Subjects

- ^ The Belmont Report, Office of the Secretary, Ethical Principles and Guidelines for the Protection of Human Subjects of Research, The National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects for Biomedical and Behavioral Research, April 18, 1979

- ^ US Department of Health and Human Services, The Nuremberg Code

- ^ American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct, Sec. 8.07. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/

- ^ "Top-Ranked Abu Ghraib Soldier Gets 8 Years in Prison". Los Angeles Times. October 21, 2004. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Welcome to the official site for the BBC Prison Study. Home – The BBC Prison Study". bbcprisonstudy.org.

- ^ Interview of Alex Haslam at The Guardian

- ^ Reicher, Steve; Haslam, Alex. "Learning from the Experiment". The Psychologist (Interview). Interviewed by Briggs, Pam. Archived from the original on February 21, 2009.

- ^ Jones, Ron (1976). "The Third Wave". The Wave Home. Archived from the original on February 2, 2015. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ "Lesson Plan: The Story of the Third Wave (The Wave, Die Welle)". lessonplanmovie.com.

- ^ "Comparing Milgram's Obedience and Zimbardo's Prison Studies". PSY 101 – Introduction to Psychology by Jeffrey Ricker, Ph.D. November 25, 2011. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- ^ "1971 Experiment 'hard to believe'". Arkansas Online. August 21, 2015. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ The Experiment (2001) – IMDb, March 8, 2001, retrieved August 19, 2021

- ^ Highfill, Samantha (July 17, 2015). "Billy Crudup turns college students into prison guards in The Stanford Prison Experiment". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Milligan, Kaitlin. "MIND FIELD Revisits The Stanford Prison Experiment in New Episode". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "Veronica Mars S 03 E 02 My Big Fat Greek Rush Week / Recap". TV Tropes. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ Rich, Nathaniel (May 11, 2018). "The Novel That Asks, 'What Went Wrong With Mankind?'". The Atlantic. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

- ^ "American Dad: Season 15 Episode 12 – TV on Google Play". play.google.com. Retrieved August 19, 2021.

References[]

- Haney, C.; Banks, W. C.; Zimbardo, P. G. (1973). "A study of prisoners and guards in a simulated prison". Naval Research Review. 30: 4–17.

- Haslam, S. A.; Reicher, S. D. (2003). "Beyond Stanford: questioning a role-based explanation of tyranny". Dialogue (Bulletin of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology). 18: 22–25.

- Haslam, S. A.; Reicher, S. D. (2006). "Stressing the group: social identity and the unfolding dynamics of responses to stress". Journal of Applied Psychology. 91 (5): 1037–1052. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.5.1037. PMID 16953766. S2CID 14058651.

- Haslam, S. A.; Reicher, S. D. (2012). "When prisoners take over the prison: A social psychology of resistance". Personality and Social Psychology Review. 16 (2): 154–179. doi:10.1177/1088868311419864. PMID 21885855. S2CID 30021002.

- Musen, K. & Zimbardo, P. G. (1991). Quiet rage: The Stanford prison study. Video recording. Stanford, CA: Psychology Dept., Stanford University.

- Reicher; Haslam, S. A. (2006). "Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC Prison Study". British Journal of Social Psychology. 45 (Pt 1): 1–40. doi:10.1348/014466605X48998. PMID 16573869.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (1971). "The power and pathology of imprisonment", Congressional Record (Serial No. 15, 1971-10-25). Hearings before Subcommittee No. 3, of the United States House Committee on the Judiciary, Ninety-Second Congress, First Session on Corrections, Part II, Prisons, Prison Reform and Prisoner's Rights: California. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office.

- Zimbardo, P. G. (2007). "Understanding How Good People Turn Evil." Interview transcript. Democracy Now!, March 30, 2007. Accessed January 17, 2015.

External links[]

- Stanford Prison Experiment, a website with info on the experiment and its impact

- Interviews with guards, prisoners, and researchers in July/August 2011 Stanford Magazine

- Zimbardo, P. (2007). From Heavens to Hells to Heroes. In-Mind Magazine.

- The official website of the BBC Prison Study

- "The Lie of the Stanford Prison Experiment", The Stanford Daily (April 28, 2005), p. 4 —Criticism by Carlo Prescott, ex-con and consultant/assistant for the experiment

- BBC news article – 40 years on, with video of Philip Zimbardo

- Philip G. Zimbardo Papers (Stanford University Archives)

- Photographs at cbsnews.com

Abu Ghraib and the experiment:

- 1971 in science

- 1971 in California

- August 1971 events in the United States

- Academic scandals

- Conformity

- Group processes

- History of psychology

- Human subject research in psychiatry

- Human subject research in the United States

- Imprisonment and detention

- Psychology experiments

- Research ethics

- Stanford University

- Fictional prisons