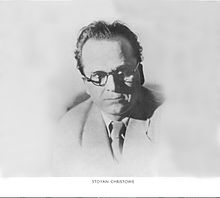

Stoyan Christowe

hideThis article has multiple issues. Please help or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Stoyan Christowe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Stoyan Naumoff [Стоян Hayмoв] 1 September 1898 Konomladi, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 28 December 1995 (aged 97) Brattleboro, Vermont, US |

| Occupation | writer, publicist, journalist, senator |

| Nationality | USA |

| Education | Valparaiso University |

| Genre | ethnology, cultural history, politics |

| Notable works | My American Pilgrimage This is my Country The Eagle and the Stork |

| Spouse | Margaret Wooters |

| Website | |

| myamericanpilgrimagemovie | |

Stoyan Christowe (also known as Stojan Hristoff) was an American author, journalist and noted Vermont political figure. Born in then Konomladi (then a part of the Ottoman Empire), he is best remembered as the author of six books written about the Balkans and as a Vermont legislator committed to promoting social justice and literacy. He was awarded an honorary doctorate from the Ss. Cyril and Methodius University of Skopje in the Republic of Macedonia and was elected an honorary member of the Macedonian Academy of Arts and Sciences (MANU).

Early life[]

Stoyan Christowe (Naumof) was born in Ottoman Macedonia, in the village of Konomladi, (present day Makrochori in Greece) on September 1, 1898 to Mitra and Christo Naumof as the first of three children (including a brother Vasil and a sister Mara). Born at a time when the Ottoman Empire was disintegrating, Stoyan, like many children, dreamed of being a komitadji, a freedom fighter, who would, unlike the heroes of bygone days, succeed in overthrowing what had become the oppressive, 500-year long Ottoman rule and bring freedom and liberty to Macedonia.[1]

After the failure of the Ilinden-Preobrazhenie Uprising, many locals started leaving, seeking better economic life in America. Some would periodically come back to the village like triumphant heroes, wearing new and exotic clothes, sporting gold teeth, carrying gold watches and most importantly telling fantastic stories about this magical America.[2] Stoyan longed to discover this place where wires encased in glass bulbs illuminated houses instead of candles; where horseless carriages, not mules, were used to transport people. He developed a burning need to live in this far off country.[citation needed] Not for money, not for prestige – no, he was driven by a passion to know and understand America and become one with it.[3]

The Amerikantzi of my boyhood days brought back to my native soil a powerful virus, an infectious America-mania that affected the young and middle-aged so that they were no longer content to till the thin mountain soil.[4]

In 1911, aged 13, Stoyan Naumoff (he would later change his name to Hristov, and in 1924 anglicize it to "Christowe") boarded the "Oceanic" in Naples, Italy—destination America. Ellis Island records indicate that he passed himself of as 16 year old Italian named Giovanni Chorbadji believing that he would be admitted to the US easier if he were not a "Balkan peasant."

Following his immigration screening at Ellis Island, he immediately headed to St. Louis. There he bunked in squalid conditions with other men from Macedonia, taking on a succession of menial jobs, first in a shoe factory, then as a soda jerk and later in St. Louis Union Station. The pay was low, the days were long and the work was both dangerous and boring to this young man, whose every waking moment seemed to be dedicated to assimilating the country he had already adopted in his mind. As he gradually learned English, he absorbed all that he could around him about this strange new world. To his uncle, and nearly all who lived in their transplanted Balkan world, the sole objective was to live as cheaply as possible for a few years, work endlessly, save money, then to return to Macedonia to "live like a pasha."

Their beings were not inoculated with the leaven of America that worked so powerfully with earlier immigrants from other lands. They were familiar with the heat of the steel mills and iron foundries and roundhouses but never came in contact with the heat of the melting pot. America had not put her finger on their minds or hearts as it had done to millions before them and as it would to their children and grandchildren.[5]

Life in the United States[]

But Stoyan did not share their goals or values and thus distanced himself from his fellow villagers. America had stolen his mind and heart and it was in this country that he planned to stay, striving to become more and more Americanized each day.

With my growing knowledge of the language America itself grew before my vision, etched itself out more clearly, and captivated my soul more enduringly. There began to seep through my being, like a strong potion, a vitalizing American serum. My young body became possessed of a passionate yearning to be absorbed by America. I longed, like a youth in love, to lay my head on the breast of America.[6]

After 3 years in St. Louis Stoyan left on a journey that would take him across America. First, traveling west, he worked for the Union Pacific Railway in Montana and Wyoming. In 1918 he enrolled at Valparaiso University to get his high school diploma and there he began his writing career as a contributor to the Torch, the college newspaper.

In 1922 he moved to a Chicago suburb in search of a real job and eventually starred freelancing as a book reviewer for the Chicago Daily News. Between 1927 and 1929 he was dispatched to the Balkans as a correspondent. During this time he was stationed in Bulgaria and became a comrade of and Elin Pelin. In 1928 Hristov visited Greece, but not his village due to fears to be conscripted as a soldier in the Greek army. As a correspondent in Sofia he interviewed Ivan Mihailov, Tsar Boris III, Vlado Chernozemski and others. Stoyan eventually became a well recognized expert on that region and his book, Heroes and Assassins, became required reading for those seeking to understand the post World War Balkans, and the factional politics of Macedonia, the principal player in it being the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organization.[7]

I belong spiritually as well as chronologically to the generations of immigrants who had to Americanize as well as acculturate, integrate, assimilate, coalesce, all at the same time. With me, the process had begun even before I had set foot on American soil. Robert Frost expressed it when he said at John F. Kennedy’s inauguration that ‘We were the land, before the land was ours.[8]

Christowe visited Bulgaria once again in 1934, just after the military government crackdown on the IMRO. In the 1930s Stoyan moved to New York City and spent ten years penning articles and writing book reviews for major magazines of the day, like the Dial, the Story Magazine, Harper's Bazaar and myriad of others, establishing himself as a respected author and critic. Stoyan's fourth book, "This is My Country", was in fact found on president Franklin D. Roosevelt bedside table when he died, a present from his wife Eleanor.

In his thirties Stoyan began a quest to untangle his roots. He had struggled with the issue of his identity since his teenage years. In 1929, in an article in The Outlook and Independent he addressed the issue candidly:[9]

What has been there result of this long gestation in the womb of America? Despite the readiness and zeal with which I tossed myself in the melting pot I still am not wholly an American and never will be. It is not my fault. I have done all I could. America will not accept me. America wanted more, it wanted complete transformation inward and outward. That is impossible in one generation. Then what is my fate? What am I? Am I still what I was before I came to America, or am I a half American and half something else? To me, precisely, there lies our tragedy. I am neither one nor the other, I am an orphan. Spiritually, physically, linguistically I have not been wholly domesticated.[10]

His passage from discombobulated newcomer, to hyphenated-American, to articulate chronicler of the migrant’s experience, offers a primary source that changes over the thirty years of his writing.

Personal life[]

In 1939, Stoyan married Margaret Wooters, a feisty young writer from Philadelphia. They had met seven years earlier while he was working on his first book, Heroes and Assassins, as writer in residence at the Yaddo Writing Retreat.

He and Margaret moved to Vermont in 1939. In 1941, shortly after the US entered World War II, Stoyan was called to duty and worked as a military analyst covering the Balkans in the War Department for two years, 1941-1943. In December 1943 he returned to Vermont and refocused on his true calling, writing.

He spent the next ten years writing articles, editorial pieces and book reviews for major American newspapers and magazines.[11] However, the matters of his identity, his roots, and his place in American society continued to haunt him.

In the early 1950s he traveled through Austria, Germany and Yugoslavia speaking at college campuses and lecturing about the American ideals. In 1952, Stoyan visited Skopje, the capital of Yugoslav Macedonia. The culture he walked away from as a child he began to embrace as a man. We also glimpse at the democratic values that Stoyan had come to cherish and the strength of his personality when, in 1953, he met Marshal Josip Broz Tito in Belgrade. In relentless defense of the freedom of expression, Stoyan did not hesitate to criticize the Marshal for his treatment of political dissidents.

The privilege to speak is a basic and important privilege…. Just think what would happen if the privilege to speak was taken away from me, you too would be affected for you could not listen to me.. let alone speak.…"

Craggy soil sprung a rebel, April 27, 1958 The New York Times

In my life I had two mothers, Macedonia who gave me birth, and America who adopted me.

source unknown

In 1985 he revisited Yugoslavia, where he was awarded with the title Doctor Honoris Causa of the in Skopje, the capital of the Republic of Macedonia.

In first half of his life, Stoyan Christowe identified himself as Bulgarian, but after World War II and the establishment of Macedonian state within the Yugoslav Federation, he redefined his understanding of who he was, and proclaimed himself an ethnic Macedonian.[12][13][14][15][16][17][18] This change was a result of the fact, that during the 20th century, the Slav Macedonian national feelings had shifted. At the beginning of the 20th century, Slavic patriots in Macedonia felt a strong attachment to their homeland, but most of them saw themselves as Bulgarians. By the middle of the 20th. century, however Macedonian Slavs began to see Macedonian and Bulgarian loyalties as mutually exclusive and Macedonian regionalism had become Macedonian nationalism.[19][20][21][22][23]

Work and political career[]

After graduating from Valparaiso University, Stojan became a correspondent for the Chicago Daily News.[24]

A 'New Yorker' from 1930 to 1939 he worked as a freelance writer and from 1941 to 1943 as a military analyst at the War Department. In Vermont, from January 1944 to 1959 he was a writer, book reviewer, lecturer and a newspaper Correspondent for The North American Newspaper Alliance in 1951-52.

In 1960, as Stoyan continued his quest to understand the meaning of 'Americanness', and, relentless in his effort to become an exemplary American, he run for a seat in the Vermont Legislature, won and served as a state representative from 1961-1962.

In 1963 he ran for a senate seat, and won the Republican nomination for his county by a landslide. Reelected in 1968, he retired in 1972 [25] and was succeeded by republican .[26]

His colleague, senator William Doyle, called him "an original" and his fight for freedom, equality and education for all is best remembered in a speech he made on the occasion of a proposed amendment to change the Constitution of Vermont.

Mr. President! The idea that our State’s Constitution needs redefining of some of its most sacred definitions is preposterous. What’s wrong with the way it’s now? Do you want the Constitution to discriminate? Our constitution speaks of natural and naturalized citizens - a distinction without discrimination. These terms give us all the right to feel equally American!

Redefining it to read ‘citizen’ and ‘natural citizen’ implies that to be a citizen is less than if you are a natural citizen. Mr. Chairman, it is just as important that America is born in the man, and maybe even more so, than the man is born in America

— Vermont Senate, 1971

Retiring from the Senate in 1972, Stoyan immediately went back to his writing. His last autobiographical novel, The Eagle and the Stork, was published in 1976 and is by far his most widely read book.

Stoyan Christowe enjoyed relative notoriety as a writer during the 1930 and 1940s. As an author he had the power to move and persuade, and his many works, especially those written during his years as a correspondent in the Balkans, add to our understanding of Southeastern European history between the two World Wars.[27] At home, during his years as a politician he served as a beacon shining light on what was good and right in America. But, his message to those not born in the US was to have faith in oneself, accept this country and its language and grow with it, and embrace one's own inner changes. And, he admonished, embrace your roots as well. "America has room for people who are Americans with origins elsewhere, it is the genius of the country."

Christowe's Legacy[]

| External image | |

|---|---|

- In 2006, the Macedonian Arts Council in a joint venture with the city government of Dover, Vermont erected a land marker, to honor its most famous resident.[28]

- In 2010,The Stoyan Christowe Scholarship Fund was established by the Macedonian Arts Council and is available only to students of literature and political science, at universities in Macedonia.[29]

Bibliography[]

Books[]

- , Robert M. McBride, (1935) (Хероu и убujцu, Мuсла 1985)

- , Thomas Y. Crowell Co., (1937) (Една Българка, Смрикаров, 1943); (Мара, Мuсла -1985)

- , Carrick & Evans, Inc., (1938)(Ова е моjaта татковuна, Мuсла 1985) - one of the favorite books of Franklin Roosevelt.

- The Lion Of Yanina, Modern Age Books, (1941) (Лavoт oд Janina, 1985)

- , Little, Brown and Company, 1947 (Ṃоjoт Амерuканскu Аu̯uлак, Мuсла 1985)

- The Eagle and the Stork, , (1976) (Орелот u штркот, Мuсла 1985)

- („Невестата на доселеникот“), изд. куќа „Дијалог“, Скопје (2010) (in Macedonian)[30]

- Partial bibliography of Stoyan Christowe's writings

See also[]

- Macedonian writers

- Macedonian American

- Macedonian nationalism

References[]

- ^ Delphos_Daily_Herald, 1903 The 1903 St. Elijas Uprising

- ^ Stoyan Christowe (January 1, 1976). The Eagle and the Stork. Harper's Magazine Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-06-121545-2.

- ^ Stoyan Christowe (January 1, 1976). The Eagle and the Stork. Harper's Magazine Press. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-06-121545-2.

- ^ Stoyan Christowe (January 1, 1976). The Eagle and the Stork. Harper's Magazine Press. p. 328. ISBN 978-0-06-121545-2.

- ^ Stoyan Christowe (January 1, 1976). The Eagle and the Stork. Harper's Magazine Press. p. 75. ISBN 978-0-06-121545-2.

- ^ The eagle and the stork, p. 75

- ^ Christowe, Stoyan (January 1, 1929). "The Secret Government of Macedonia". : 332–335. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ The Eagle and the Stork, p. 74

- ^ Stanley I. Kutler (1976). "Assimilation: Two views". Looking for America: Since 1865 (PDF). Canfield Press. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-06-384761-3.

- ^ Christowe, Stoyan (December 4, 1929). "Half an American". The Outlook and Independent: 530–531.

- ^ Homo Vermonticus, Vermont Life, Automn Edition, 1953

- ^ America in the Age of the Titans: The Progressive Era and World War I, Sean Dennis Cashman, NYU Press, 1988, ISBN 0814714110, p. 184.

- ^ Culture and history of the Bulgarian people, their Bulgarian and American parallels, Duquesne University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, April 1981, Walter W. Kolar, p. 133.

- ^ "While I am not a whole American, neither am I what I was when I first landed here; that is, a Bulgarian.... I have outwardly and inwardly deviated so much from a Bulgarian that when recently visiting in that country I felt like a foreigner.... In Bulgaria I am not wholly a Bulgarian; in the United States not wholly an American." Stoyan Christowe in 1919, cited in Ellis Island: An Illustrated History of the Immigrant Experience, edited by Ivan Chermayeff et al. (New York: Macmillan, 1991), ISBN 0025844415, p. 74.

- ^ This is my country, autobiography by Stoyan Christowe, Carrick & Evans, 1938, p. 262: Thought born a Bulgarian, I had never before been in Bulgaria proper, having come directly to America from Macedonia.

- ^ Para una tipología del exilio literario sudeslavo. Francisco Javier, Departamento de Filología Románica, Filología Eslava y Lingüística General, Universidad Complutense de Madrid: "born in Bulgarian village near Salonica,... after 1944 he was attracted by Tito's postwar Macedonism". p. 179.

- ^ Salvation abroad, Macedonian migration to North America and the making of modern Macedonia, 1870-1970, Gregory Michaelidis, Doctor of Philosophy, 2005, p.16: Coming initially as a sojourner following other men from his native village of Konomladi, Christowe saw himself, alternately, as both Macedonian and Bulgarian, a common phenomenon among early-century migrants. His passage from discombobulated newcomer, to hyphenated-American, to articulate chronicler of the migrant’s experience, offers an exquisite primary source that changes over the thirty years of his writing.

- ^ Selected works of Stoyan Christowe were published on Macedonian language in 1985, when he has given his approval to the editors, all the passages related to him and containing the identification Bulgarian to be replaced with Macedonian. Џукески, Александар: Стојан Христов во одбрана на македонскиот литературен јазик. Избор од емитуваните содржини на Третата програма на Радио Скопје. 1985, стр. 75 - 81. (Stoyan Christowe in defense of the Macedonian Literary Language, A selection of broadcasts on MKRadio, Channel 3, Skopje 1985. Pg.75-81)

- ^ Region, Regional Identity and Regionalism in Southeastern Europe, Ethnologia Balkanica Series, Klaus Roth, Ulf Brunnbauer, LIT Verlag Münster, 2010, ISBN 3825813878, p. 127.

- ^ "At the end of the First World War there were very few historians or ethnographers, who claimed that a separate Macedonian nation existed... Of those Slavs who had developed then some sense of national identity, the majority probably considered themselves to be Bulgarians, although they were aware of differences between themselves and the inhabitants of Bulgaria... The question as of whether a Macedonian nation actually existed in the 1940s when a Communist Yugoslavia decided to recognize one is difficult to answer. Some observers argue that even at this time it was doubtful whether the Slavs from Macedonia considered themselves to be a nationality separate from the Bulgarians. "The Macedonian conflict: ethnic nationalism in a transnational world", Loring M. Danforth, Princeton University Press, 1997, ISBN 0-691-04356-6, pp. 65-66.

- ^ The key fact about Macedonian nationalism is that it is new: in the early twentieth century, Macedonian villagers defined their identity religiously—they were either "Bulgarian," "Serbian," or "Greek" depending on the affiliation of the village priest. While Bulgarian was most common affiliation then, mistreatment by occupying Bulgarian troops during WWII cured most Macedonians from their pro-Bulgarian sympathies, leaving them embracing the new Macedonian identity promoted by the Tito regime after the war. "Modern hatreds: the symbolic politics of ethnic war." New York: Cornell University Press. Kaufman, Stuart J. (2001); p. 193. ISBN 0-8014-8736-6.

- ^ Zielonka, Jan; Pravda, Alex (2001). Democratic consolidation in Eastern Europe. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-19-924409-6. Unlike the Slovene and Croatian identities, which existed independently for a long period before the emergence of SFRY Macedonian identity and language were themselves a product federal Yugoslavia, and took shape only after 1944.

- ^ Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Stephan Thernstrom, Belknap Press, 1980, ISBN 0674375122, p. 692, The Macedonians: Immigrants from Macedonia came to the United States in significant numbers during the early years of the 20th century. Until World War II almost all of them thought of themselves as Bulgarians and identified themselves as Bulgarians or Macedonian Bulgarians...The greatest advances in the growth of a distinct Macedonian-American community have occurred since the late 1950s. The new immigrants came from Yugoslavia's Socialist Republic of Macedonia, where since World War II they had been educated to believe that Macedonians composed a culturally and linguistically distinct nationality; thc historic ties with Bulgarians in particular were deemphasized. These new immigrants not only are convinced of their own Macedonian national identity but also have been instrumental in transmitting these feelings to older Bulganan-oriented immigrants from Macedonia.

- ^ Elliott Robert Barkan (January 1, 2001). Making it in America: A Sourcebook on Eminent Ethnic Americans. ABC-CLIO. p. 72. ISBN 978-1-57607-098-7.

- ^ Christowe's resignation stirs the area, Brattleboro Reformer, April 1972

- ^ STILTS, JOSH (August 27, 2012). "Robert Gannett - 'genuine statesman' - dies at 95". Battleboro Reformer. Retrieved July 21, 2015.

- ^ Christowe, Stoyan (July 1, 1939). "Where the Axes Cross". : 408–411.

- ^ Avard, Christian (2010). "Pilgrimage ended in Dover". Deerfield Valley News. Retrieved July 17, 2015.

- ^ "The Stoyan Christowe Endowment Fund". Macedonian Arts Council. 2015. Retrieved July 2, 2015.

- ^ Објавен досега непознат роман од Стојан Христов (Stoyan Christowe’s last unknown manuscript published in Macedonian.)

External links[]

- Stoyan Christowe - Vermont Historical Society.

- Bibliography of Stoyan Christowe's works

- My American Pilgrimage Movie

- Macedonian Arts Council

- Works by or about Stoyan Christowe at Internet Archive

- 1898 births

- 1995 deaths

- Macedonian writers

- American people of Macedonian descent

- Bulgarians from Aegean Macedonia

- American people of Bulgarian descent

- People from Kastoria (regional unit)