Strafgesetzbuch section 86a

The German Strafgesetzbuch (Criminal Code) in section § 86a outlaws "use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations" outside the contexts of "art or science, research or teaching". The law does not name the individual symbols to be outlawed, and there is no official exhaustive list. However, the law has primarily been used to outlaw Nazi, Communist, and Islamic extremist symbols. The law was adopted during the Cold War and notably affected the Communist Party of Germany, which was banned as unconstitutional in 1956, the Socialist Reich Party (banned in 1952) and several small far-right parties.

The law prohibits the distribution or public use of symbols of unconstitutional groups—in particular, flags, insignia, uniforms, slogans and forms of greeting.[1]

Text[]

The relevant excerpt of the German criminal code reads:[1][2][3]

§ 86 StGB Dissemination of Means of Propaganda of Unconstitutional Organizations

- Whoever domestically disseminates or produces, stocks, imports or exports or makes publicly accessible through data storage media for dissemination domestically or abroad, means of propaganda:

shall be punished with imprisonment for not more than three years or a fine.

- of a party which has been declared to be unconstitutional by the Federal Constitutional Court or a party or organization, as to which it has been determined, no longer subject to appeal, that it is a substitute organization of such a party;

- ...

- means of propaganda, the contents of which are intended to further the aims of a former National Socialist organization,

- ...

- Subsection (1) shall not be applicable if the means of propaganda or the act serves to further civil enlightenment, to avert unconstitutional aims, to promote art or science, research or teaching, reporting about current historical events or similar purposes.

§ 86a StGB Use of Symbols of Unconstitutional Organizations

- Whoever:

shall be punished with imprisonment for not more than three years or a fine.

- domestically distributes or publicly uses, in a meeting or in writings (§ 11 subsection (3)) disseminated by him, symbols of one of the parties or organizations indicated in § 86 subsection (1), nos. 1, 2 and 4; or

- produces, stocks, imports or exports objects which depict or contain such symbols for distribution or use domestically or abroad, in the manner indicated in number 1,

- Symbols, within the meaning of subsection (1), shall be, in particular, flags, insignia, uniforms, slogans and forms of greeting. Symbols which are so similar as to be mistaken for those named in sentence 1 shall be deemed to be equivalent thereto.

- The exceptions from §86 subsection (3) and (4) apply accordingly.

Symbols affected[]

The text of the law does not name the individual symbols to be outlawed, and there is no official exhaustive list. A symbol may be a flag, emblem, uniform, or a motto or greeting formula. The prohibition is not tied to the symbol itself but to its use in a context suggestive of association with outlawed organizations. Thus, the Swastika is outlawed if used in a context of völkisch ideology, while it is legitimate if used as a symbol of religious faith, particularly any South Eastern or East Asian religions. Similarly, the Wolfsangel is outlawed if used in the context of the Junge Front but not in other contexts such as heraldry, or as the emblem of "landscape poet" Hermann Löns[citation needed].

Due to the law, German Neo-Nazis took to displaying modified symbols similar but not identical with those outlawed. In 1994, such symbols were declared equivalent to the ones they imitate (Verbrechensbekämpfungsgesetz Abs. 2). As a result of the ban on Nazi symbols, German Neo-Nazis have used older symbols such as the black-white-red German Imperial flag (which was also briefly used by the Nazis alongside the party flag as one of two official flags of Nazi Germany from 1933 until 1935) as well as variants of this flag such as the one with the Eisernes Kreuz (Iron Cross) and the Reichsdienstflagge variants, the Imperial-era Reichskriegsflagge, and the flag of the Strasserite Black Front – a splinter Nazi organization – as alternatives.[citation needed]

Affected by the law according to Federal Constitutional Court of Germany rulings are:

- Sozialistische Reichspartei (1952)[4]

- Kommunistische Partei Deutschlands (1956)[5]

- Volkssozialistische Bewegung Deutschlands/Partei der Arbeit (1982)

- Aktionsfront Nationaler Sozialisten/Nationale Aktivisten (1983)

- Deutsche Alternative (1992)

- Nationalistische Front (1992)

- Wiking-Jugend (1994)

- Freiheitliche Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (1995)

- Blood and Honour, Germany chapter (2000)

Symbols known to fall under the law are:

- the swastika as a symbol of the Nazi Party, prohibited in all variants, including mirrored, inverted etc. (exceptions are only applied to swastikas used as religious symbols in Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain temples)

- a stylized Celtic cross, prohibited as a symbol of the VSBD/PdA and in the variant used by the White Power movement. The legal status of the symbol used in non-political contexts is uncertain, but non-political use is not acted upon in practice.[6]

- the solar cross as a symbol of the Ku Klux Klan (symbol of cross burning from the "second Klan" era onward),[7] the German Faith Movement, the Thule Society and the 5th and 11th Waffen SS divisions

- the Sig rune as used by the SS

- the Sturmabteilung emblem

- the legal status of the Othala rune is disputed;[clarification needed] prohibited as a symbol of the Hitler-Jugend/Wiking-Jugend. Post war military usage was incorporated into the Bundeswehr with a stylized "Othala rune" being featured on the shoulder insignia of the Hauptfeldwebel with it also being used by the ranks succeeding it.[8][circular reference]

- the Wolfsangel as used by the 2nd, 4th and 34th Waffen SS divisions, Hitlerjugend and Junge Front

- badges (2002)[9]

- Reichskriegsflagge: prohibited in the Third Reich version including a swastika.

- the "Heil Hitler" greeting (1970)[10]

- the "Sieg Heil" greeting (1990)[11]

- Unsere/Meine Ehre heißt Treue, along with the Totenkopf symbol, as the motto of the Waffen-SS and Mit deutschem Gruß as the verbal equivalent of the Hitler salute.[12]

- The Reichsadler with the Nazi swastika.

- the Horst-Wessel-Lied (the anthem of the Nazi Party) and Unsre Fahne flattert uns voran (a song of the Hitler-Jugend) (1991)[13]

- the hammer and sickle, red star and red flag when used as emblems of the Communist Party of Germany

- The Black Standard of the Islamic State; widely considered the chief sigil or flag of the jihadi group.[14][15]

- the People's Protection Units (YPG) pennant was explicitly banned as symbol related to the PKK on 2 March 2017,[16][17][18] even though the organisation itself is not currently recognised as terrorist.[19]

Illustration of the emblems mentioned in the list above:

Nazi swastika

Party Eagle (Parteiadler) of the Nazi Party.

Solar cross

Celtic cross as used by White Power movements

Broken solar cross of the Thule Society and the German Faith Movement

Ku Klux Klan (1915–current) "fiery cross" from a 1905 novel about the Klan, and the novel's 1915 movie adaptation[20][21]

Odal rune

Sturmabteilung emblem

Schutzstaffel sig runes

Flag of the Nazi Party

Reichskriegsflagge 1938–1945 (National war flag)

Reichsdienstflagge 1935–1945 (Reich Service Flag)

Emblem of the Communist Party of Germany (redrawn after a historical lapel pin)

Reverse side of the Red flag of the Communist Party of Germany

IS / ISIL / ISIS / Daesh version of the Black Standard

Flag of the People's Protection Units

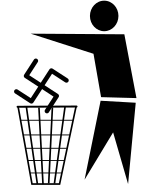

Anti-fascism symbols[]

In 2005, a controversy was stirred about the question whether the paragraph should be taken to apply to the display of crossed-out swastikas as a symbol of anti-fascism.[22] In late 2005 police raided the offices of the punk rock label and mail order store "Nix Gut Records" and confiscated merchandise depicting crossed-out swastikas and fists smashing swastikas. In 2006 the Stade police department started an inquiry against anti-fascist youths using a placard depicting a person dumping a swastika into a trashcan. The placard was displayed in opposition to the campaign of right-wing nationalist parties for local elections.[23]

On Friday 17 March 2006, a member of the Bundestag, Claudia Roth, reported herself to the German police for displaying a crossed-out swastika in multiple demonstrations against Neo-Nazis, and subsequently got the Bundestag to suspend her immunity from prosecution. She intended to show the absurdity of charging anti-fascists with using fascist symbols: "We don't need prosecution of non-violent young people engaging against right-wing extremism." On 15 March 2007, the Federal Court of Justice of Germany (Bundesgerichtshof) reversed the charge, holding that the crossed-out symbols were "clearly directed against a revival of national-socialist endeavors", thereby settling the dispute for the future.[24][25][26]

Application to forms of media[]

Section 86a includes a social adequacy clause that allows the use of the symbols that fall within it for the purposes of "art or science, research or teaching". This generally as allows these symbols to be used in literature, television shows as with the 1960s Star Trek episode, Patterns of Force, itself allowed after 1995,[27] films, and other works of art without censoring or modification and stay within the allowance for the clause. For example, German theaters were allowed to screen Raiders of the Lost Ark and Inglourious Basterds—films which feature frequent displays of Nazi symbols—without censorship.

Up until 2018, video games were not included in the social adequacy clause. A High District Frankfurt Court ruling in 1998 over the video game Wolfenstein 3D determined that because video games do attract young players, "this could lead to them growing up with these symbols and insignias and thereby becoming used to them, which again could make them more vulnerable for ideological manipulation by national socialist ideas".[28] Since this ruling, the Unterhaltungssoftware Selbstkontrolle (USK), the German content ratings board, would refuse to rate any game that includes symbols under Section 86a, effectively banning them from retail sales within Germany. This led to software developers and publishers to either avoid publication in Germany, or create alternate, non-offending symbols to replace them, such as in Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, where the developer had to replace the game's representation of Adolf Hitler with a version without the moustache and named "Chancellor Heiler".[28]

In August 2018, the German government reversed this ruling as a result of a ruling from April 2018. The web-based game Bundesfighter II Turbo was released prior to the September 2017 elections, which included parodies of the candidates fighting each other; this included Alexander Gauland, who had a special move that involved Swastika imagery. When this was noticed by public authorities, they began prosecution of the game in December 2017, submitting it to the Public Prosecutor General's office for review based on the Wolfenstein 3D decision. The Attorney General declined to consider the game illegal under Section 86a, stating that the 1998 ruling was outdated; since then, USK had adopted age ratings for video games, and that there was no reason not to consider video games as art within the social adequacy clause.[29] As a result, the Supreme Youth Protection Authority of the Federal States adapted the Attorney General's ruling to be applicable for all video games within Germany, and subsequently the USK announced in August 2018 this change; USK will still review all games to judge if the use of imagery under Section 86a remains within the social adequacy clause and deny ratings to those that fail to meet this allowance.[28]

See also[]

- Bans on Communist symbols

- Censorship

- Freedom of speech

- Horst-Wessel-Lied

- List of symbols designated by the Anti-Defamation League as hate symbols in the United States

- Memory law

- Modern display of the Confederate flag

- Nazi symbolism

- Post–World War II legality of Nazi flags

- Swastika

- Thor Steinar

- Verbotsgesetz 1947 in Austria

References[]

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Section 86a Use of Symbols of Unconstitutional Organizations". Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch, StGB). German Law Archive.

- ^ Andreas Stegbauer; German Law Journal. "The Ban of Right-Wing Extremist Symbols According to Section 86a of the German Criminal Code" (PDF). germanlawjournal.com.

- ^ World Bank. "GERMAN CRIMINAL CODE Criminal Code in the version promulgated on 13 November 1998, Federal Law Gazette [Bundesgesetzblatt] I p. 3322, last amended byArticle 3 of the Law of 2 October 2009, Federal Law Gazette I p. 3214" (PDF). worldbank.org.

- ^ Urteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts vom 23. Oktober 1952, Aktenzeichen 1 BvB 1/51; Fundstelle: 2, 1

- ^ Urteil des Bundesverfassungsgerichts vom 17. August 1956, Aktenzeichen 1 BvB 2/51; Fundstelle: BVerfGE 5, 85 Archived 12 February 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Isoliertes Verwenden eines stilisierten Keltenkreuzes grundsätzlich strafbar" (in German). Der Bundesgerichtshof. 14 November 2008.

- ^ Huhn, Wilson (1970). "CROSS BURNING AS HATE SPEECH UNDER THE FIRST AMENDMENT TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION". amsterdamlawforum.org. Free University Amsterdam. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

In the United States one particularly virulent form of expression is associated with hatred and prejudice – the burning of a cross. Originally a traditional Scottish custom of signalling, following the American Civil War cross burning was adopted by guerrilla groups such as the Ku Klux Klan (Klan) as a symbol of racial supremacy and as a means of terrorising the newly freed slaves. The burning cross was glorified in the wicked movie The Birth of a Nation (1915) that depicted the Klan as heroes and saviors. Cross burnings were common at Klan rallies throughout the 1920s at a time when lynchings were commonplace and the Klan was at the height of its power. The burning cross was used as a warning and a threat to any person seeking to improve the political or economic condition of the black race.

- ^ Hauptfeldwebel (rank)

- ^ "Gauwinkel". Die Tageszeitung: Taz (in German). taz.de. 2 December 2005. p. 13.

- ^ Entscheidung des Oberlandesgerichts Celle, Neue Juristische Wochenschrift 1970, 2257

- ^ Entscheidung des Oberlandesgerichts Düsseldorf vom 6. September 1990, (MDR) 1991, 174

- ^ Entscheidung des Bundesgerichtshofes, Aktenzeichen 3 StR 280/76, 27,1

- ^ Entscheidung des Oberlandesgerichts Celle, NJW 1991, 1498

- ^ Eddy, Melissa (12 September 2014). "Germany Bans Support for ISIS". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 November 2014.

Germany on Friday [September 12, 2014] announced a ban on activities that support the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, including any displays of its black flag, as part of an effort to suppress the extremist group’s propaganda and recruitment work among Germans.

- ^ "Germany 2014 human rights report - US Department of State" (PDF). state.gov. United States Department of State. 2014. p. 11. Retrieved 11 September 2018.

On September 12 (2014), the Federal Interior Ministry banned any activities of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), including recruitment, fundraising, and the use of the group’s symbols under the name “Islamic State” (German: Islamischer Staat), such as the black flag bearing ISIL’s name.

- ^ "German police raid leftist for posting Kurdish YPG flag - DW - 19.08.2017". DW.COM.

- ^ "German lawmaker sparks criticism after displaying banned YPG flag in parliament". DailySabah. 21 November 2017.

- ^ Gude, Hubert (10 March 2017). "De Maizière verbietet Öcalan-Porträts" [De Maizière bans portraits of Öcalan]. Spiegel Online (in German). Hamburg. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Yücel, Deniz (24 February 2016). "Gute Kurden, böse Kurden. Wer ist Terrorist?" [Good Kurds, bad Kurds. Who is terrorist?]. Welt (in German). Berlin. Retrieved 4 February 2018.

- ^ Dixon, Thomas, 1864–1946. Arthur I. Keller, illustr. The clansman; an historical romance of the Ku Klux Klan New York Doubleday, pages 324-327

- ^ Cecil Adams (18 June 1993). "Why does the Ku Klux Klan burn crosses?". The Straight Dope. Retrieved 24 December 2009.

- ^ "Stuttgart Seeks to Ban Anti-Fascist Symbols". Journal Chrétien. 4 April 2006.

- ^ "Plakate sind Thema im Landtag" (in German). Tageblatt Online. 23 September 2006. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009.

- ^ "Bundesgerichtshof, decision (Urteil) of the 15 March 2007, file reference: 3 StR 486/06" (PDF).

- ^ "Durchgestrichenes Hakenkreuz kein verbotenes Kennzeichen" (in German). Der Bundesgerichtshof. 15 March 2007.

- ^ "Bundesgerichtshof: Anti-Nazi-Symbole sind nicht strafbar" (in German). Der Spiegel. 15 March 2007.

- ^ "5 original Star Trek episodes that were banned overseas".

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Orland, Kyle (10 August 2018). "Germany says games with Nazi symbols can get "artistic" exception to ban". Ars Technica. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ^ Schwiddessen, Sebastian (8 May 2018). "German Attorney General: Video game with Swastika does not violate the law; constitutes art". . Retrieved 26 August 2019.

External links[]

- German criminal law

- Anti-fascism in Germany

- Censorship in Germany

- Nazi symbolism