Street Fighting Man

| "Street Fighting Man" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Single by the Rolling Stones | ||||

| from the album Beggars Banquet | ||||

| B-side | "No Expectations (US) Surprise, Surprise & Everybody Needs Somebody to Love (UK)" | |||

| Released |

| |||

| Recorded | April–May 1968 | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length |

| |||

| Label | London | |||

| Songwriter(s) | Jagger/Richards | |||

| Producer(s) | Jimmy Miller | |||

| The Rolling Stones US singles chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Audio sample | ||||

| ||||

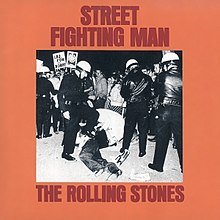

| Alternative cover | ||||

French single picture sleeve | ||||

"Street Fighting Man" is a song by English rock band the Rolling Stones featured on their 1968 album Beggars Banquet. Called the band's "most political song",[4] Rolling Stone ranked the song number 301 on its list of the 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.

Background[]

In an interview with Marc Myers, Keith Richards said that he wrote most of the music for the song in late 1966 or early 1967, and got the "dry, crisp" sound that he wanted by strumming an acoustic guitar with an open tuning in front of a portable Philips cassette recorder microphone. The melody was influenced by the sound of police sirens.[5]

Originally titled and recorded as "Did Everyone Pay Their Dues?", containing the same music but very different lyrics about adult brutality,[5] "Street Fighting Man" is known as one of Mick Jagger and Keith Richards' most politically inclined works to date. Jagger allegedly wrote it about Tariq Ali after he attended a 1968 anti-war rally at London's US embassy, during which mounted police attempted to control a crowd of 25,000.[6][7] He also found inspiration in the rising violence among student rioters on Paris' Left Bank,[8] the precursor to a period of civil unrest in May 1968.

Jagger explained in a 1995 interview with Jann Wenner in Rolling Stone:

Yeah, it was a direct inspiration, because by contrast, London was very quiet ... It was a very strange time in France. But not only in France but also in America, because of the Vietnam War and these endless disruptions ... I thought it was a very good thing at the time. There was all this violence going on. I mean, they almost toppled the government in France; de Gaulle went into this complete funk, as he had in the past, and he went and sort of locked himself in his house in the country. And so the government was almost inactive. And the French riot police were amazing.[9]

Richards said, only a few years after recording the track in a 1971 Rolling Stone interview with Robert Greenfield, that the song had been "interpreted thousands of different ways". He mentioned how Jagger went to the Grosvenor Square demonstrations in London and was even charged by the police, yet he ultimately claims, "it really is ambiguous as a song".[10]

Recording[]

Recording on "Street Fighting Man" took place at Olympic Sound Studios from April until May 1968. With Jagger on lead vocals and both he and Richards on backing, Brian Jones performs the song's distinctive sitar and also tamboura. Richards plays the song's acoustic guitars as well as bass, the only electric instrument on the recording. Charlie Watts plays drums while Nicky Hopkins performs the song's piano which is most distinctly heard during the coda. Shehnai is performed on the track by Dave Mason. On the earlier, unreleased "Did Everybody Pay Their Dues" version, Rick Grech played a very prominent electric viola.

Watts said in 2003:

"Street Fighting Man" was recorded on Keith's cassette with a 1930s toy drum kit called a London Jazz Kit Set, which I bought in an antiques shop, and which I've still got at home. It came in a little suitcase, and there were wire brackets you put the drums in; they were like small tambourines with no jangles ... The snare drum was fantastic because it had a really thin skin with a snare right underneath, but only two strands of gut ... Keith loved playing with the early cassette machines because they would overload, and when they overload they sounded fantastic, although you weren't meant to do that. We usually played in one of the bedrooms on tour. Keith would be sitting on a cushion playing a guitar and the tiny kit was a way of getting close to him. The drums were really loud compared to the acoustic guitar and the pitch of them would go right through the sound. You'd always have a great backbeat.[11]

Richards commented on the recording:

The basic track of that was done on a mono cassette with very distorted recording, on a Philips with no limiters. Brian is playing sitar, it twangs away. He's holding notes that wouldn't come through if you had a board, you wouldn't be able to fit it in. But on a cassette if you just move the people, it does. Cut in the studio and then put on a tape. Started putting percussion and bass on it. That was really an electronic track, up in the realms.[10]

Critical reception[]

The song opens with a strummed acoustic guitar riff. In his review, Richie Unterberger says of the song, "[I]t's a great track, gripping the listener immediately with its sudden, springy guitar chords and thundering, offbeat drums. That unsettling, urgent guitar rhythm is the mainstay of the verses. Mick Jagger's typically half-buried lyrics seem at casual listening like a call to revolution."[12]

Everywhere I hear the sound of marching, charging feet, boy

'Cause summer's here and the time is right for fighting in the street, boy

Hey! think the time is right for a palace revolution, but where I live the game to play is compromise solution

Hey, said my name is called Disturbance; I'll shout and scream, I'll kill the King, I'll rail at all his servants

Well now what can a poor boy do except to sing for a rock & roll band?

Cause in sleepy London Town there's just no place for a street fighting man, no

Unterberger continues, "Perhaps they were saying they wished they could be on the front lines, but were not in the right place at the right time; perhaps they were saying, as John Lennon did in the Beatles' "Revolution", that they didn't want to be involved in violent confrontation. Or perhaps they were even declaring indifference to the tumult."[12]

Other writers' interpretations varied. In 1976, Roy Carr assessed it as a "great summer street-corner rock anthem on the same echelon as 'Summer in the City', 'Summertime Blues', and 'Dancing in the Street'."[8] In 1979, Dave Marsh wrote that as part of Beggars Banquet, "Street Fighting Man" was the "keynote, with its teasing admonition to do something and its refusal to admit that doing it will make any difference; as usual, the Stones were more correct, if also more faithless, philosophers than any of their peers."[13] In fact, the second line of the first verse alludes to "Dancing in the Street"; a similar line had been present in the aforementioned song, where "fighting" instead was "dancing".[14]

Backlash in the United States[]

The song was released within a week of the violent confrontations between the police and anti-Vietnam War protesters at the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.[12] Worried about the possibility of the song inciting further violence, Chicago radio stations refused to play the song. This was much to the delight of Mick Jagger, who stated: "I'm rather pleased to hear they have banned (the song). The last time they banned one of our records in America, it sold a million."[15] Jagger said he was told they thought the record was subversive, to which he snapped: "Of course it's subversive! It's stupid to think you can start a revolution with a record. I wish you could."[15]

Keith Richards weighed into the debate when he said that the fact a couple of radio stations in Chicago banned the record "just goes to show how paranoid they are". At the same time they were still requested to do live appearances and Richards said: "If you really want us to cause trouble, we could do a few stage appearances. We are more subversive when we go on stage."[15]

Retrospective views[]

Bruce Springsteen would comment in 1985, after including "Street Fighting Man" in the encores of some of his Born in the U.S.A. Tour shows: "That one line, 'What can a poor boy do but sing in a rock and roll band?' is one of the greatest rock and roll lines of all time ... [The song] has that edge-of-the-cliff thing when you hit it. And it's funny; it's got humour to it."[16]

Jagger continues in the Rolling Stone interview when asked about the song's resonance thirty years on; "I don't know if it [has any]. I don't know whether we should really play it. I was persuaded to put it [on Voodoo Lounge Tour] because it seemed to fit in, but I'm not sure if it really has any resonance for the present day. I don't really like it that much."[9] Despite this, the song has been performed on a majority of the Stones' tours since its introduction to their canon of work, and is usually played second to last before their usual closing track Jumpin' Jack Flash.

Releases[]

Released as Beggars Banquet's lead single in August 1968 in the US, "Street Fighting Man" was popular on release, but did not reach the Top 40 (reaching number 48) of the US charts in response to many radio stations' refusal to play the song based on what were perceived as subversive lyrics.[15] "No Expectations", also from Beggars Banquet, was used as the single's B-side. As usual with Stones' album tracks in the 60s, the single did not see a release at the time in the UK. It was released in 1971 (backed with "Surprise, Surprise", previously released in the UK on the various artists Decca LP compilation "14" in 1965.

The US single version was released in mono with an additional vocal overdub on the choruses, and thus is different from the Beggars Banquet album's stereo version. While many of the US London picture sleeves are rare and collectable, the sleeve for this single is particularly scarce and is considered their most valuable.

The album version of the song has been included on the compilations Through the Past, Darkly (Big Hits Vol. 2) (1969), Hot Rocks 1964-1971 (1971), 30 Greatest Hits (1977), Singles Collection: The London Years (1989 edition), Forty Licks (2002), and GRRR! (2012). The US single version was included on the 2002 edition of Singles Collection: The London Years and on Stray Cats, a collection of singles and rarities released as part of the box set The Rolling Stones in Mono (2016).

A staple at Rolling Stones live shows since the band's American Tour of 1969, concert recordings of the song have been captured and released for the live albums Get Yer Ya-Ya's Out! (recorded 1969, released 1970), Stripped (1995; rereleased on Totally Stripped in 2016), Live Licks (recorded 2003, released 2004), and Hyde Park Live (2013).

Personnel[]

The Rolling Stones

- Mick Jagger – vocals, claves

- Keith Richards – acoustic guitars, bass guitar

- Brian Jones – sitar, tamboura

- Charlie Watts – drums

Additional personnel

- Dave Mason – shehnai, bass drum

- Nicky Hopkins – piano

Charts[]

| Chart (1968) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| Austria (Ö3 Austria Top 40)[17] | 7 |

| Belgium (Ultratop 50 Flanders)[18] | 13 |

| Canada Top Singles (RPM)[19] | 32 |

| Germany (Official German Charts)[20] | 7 |

| Netherlands (Single Top 100)[21] | 5 |

| Switzerland (Schweizer Hitparade)[22] | 4 |

| US Billboard Hot 100[23] | 48 |

| Chart (1971) | Peak position |

| UK Singles (OCC)[24] | 21 |

References[]

- ^ Milward, John (2013). Crossroads: How the Blues Shaped Rock 'n' Roll (and Rock Saved the Blues). Northeastern. p. 128. ISBN 978-1555537449.

- ^ Willis, Ellen (2011). Out of the Vinyl Deeps: Ellen Willis on Rock Music. University of Minnesota Press. p. 80. ISBN 978-0816672837.

- ^ Schaffner, Nicholas (1982). The British Invasion: From the First Wave to the New Wave. Mcgraw-Hill. p. 77. ISBN 978-0070550896.

- ^ "News". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 15 March 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Myers, Marc (2016). Anatomy of a Song. Grove Press. pp. 121–125. ISBN 978-1-61185-525-8.

- ^ Azania, Malcolm. "Tariq Ali: The time is right for a palace revolution" Archived 4 December 2017 at the Wayback Machine. Vue Weekly. 2008 (accessed 5 June 2017).

- ^ "Tariq Ali: The time is right for a palace revolution" Archived 17 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine. TruthDig. 2015 (accessed 5 June 2017).

- ^ Jump up to: a b Roy Carr, The Rolling Stones: An Illustrated Record, Harmony Books, 1976. ISBN 0-517-52641-7. p. 55.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Wenner, Jann. "Jagger Remembers". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 14 July 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Greenfield, Robert. "Keith Richards – Interview". Rolling Stone (magazine) 19 August 1971.

- ^ Jagger, Mick; Richards, Keith; Watts, Charlie; Wood, Ronnie (2003). According to the Rolling Stones. Chronicle Books. pp. 116, 119. ISBN 0811840603.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Unterberger, Richie. "Rolling Stones: Street Fighting Man – review". AllMusic. Retrieved 22 July 2006.

- ^ Rolling Stone Record Guide, Rolling Stone Press, 1979. ISBN 0-394-73535-8 pp. 329-330

- ^ Peraino, Judith A. (September 2015). "Mick Jagger as Mother" (PDF). Social Text. 33 (3): 94. doi:10.1215/01642472-3125707. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Paytress, Mark (2003). The Rolling Stones: Off the Record. Omnibus Press. p. 153. ISBN 0-7119-8869-2.

- ^ Marsh, Dave. Glory Days: Bruce Springsteen in the 1980s. Pantheon Books, 1987. ISBN 0-394-54668-7. pp. 229-230.

- ^ "Austriancharts.at – The Rolling Stones – Street Fighting Man" (in German). Ö3 Austria Top 40. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Ultratop.be – The Rolling Stones – Street Fighting Man" (in Dutch). Ultratop 50. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Top RPM Singles: Issue 5863." RPM. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Offiziellecharts.de – The Rolling Stones – Street Fighting Man" (in German). GfK Entertainment Charts. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Dutchcharts.nl – The Rolling Stones – Street Fighting Man" (in Dutch). Single Top 100. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Swisscharts.com – The Rolling Stones – Street Fighting Man". Swiss Singles Chart. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "The Rolling Stones Chart History (Hot 100)". Billboard. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ^ "Rolling Stones: Artist Chart History". Official Charts Company. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

External links[]

- 1968 singles

- 1968 songs

- Decca Records singles

- London Records singles

- Oasis (band) songs

- Obscenity controversies in music

- Protest songs

- Raga rock songs

- Rage Against the Machine songs

- Ramones songs

- Song recordings produced by Jimmy Miller

- Songs written by Jagger/Richards

- The Rolling Stones songs