Sulla

Sulla | |

|---|---|

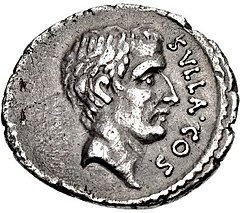

Portrait of Sulla on a denarius minted in 54 BC by his grandson Pompeius Rufus[1] | |

| Born | 138 BC[2][3][4][5] |

| Died | 78 BC (aged 60) |

| Nationality | Roman |

Notable credit(s) | Constitutional reforms of Sulla |

| Office | Dictator (82–79 BC)[6] Consul (88, 80 BC) |

| Political party | Optimates |

| Opponent(s) | Gaius Marius |

| Spouse(s) | |

| Children |

|

| Military career | |

| Service years | 107–82 BC |

| Wars | |

| Awards | Grass Crown |

Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix[7] (/ˈsʌlə/; 138–78 BC), commonly known as Sulla, was a Roman general and statesman. He won the first large-scale civil war in Roman history, and became the first man of the republic to seize power through force.

Sulla had the distinction of holding the office of consul twice, as well as reviving the dictatorship. He was a gifted and innovative general and achieved numerous successes in wars against different opponents, both foreign and domestic. Sulla rose to prominence during the war against the Numidian king Jugurtha, whom he captured as a result of Jugurtha's betrayal by the king's allies, although his superior Gaius Marius took credit for ending the war. He then fought successfully against Germanic tribes during the Cimbrian War, and Italic tribes during the Social War. He was awarded the Grass Crown for his command in the latter war.

Sulla played an important role in the long political struggle between the optimates and populares factions at Rome. He was a leader of the former, which sought to maintain the senatorial supremacy against the populist reforms advocated by the latter, headed by Marius. In a dispute over the command of the war against Mithridates, initially awarded to Sulla by the Senate, but withdrawn as a result of Marius' intrigues, Sulla marched on Rome in an unprecedented act and defeated Marian forces in battle. The populares nonetheless seized power once he left with his army to Asia. He returned victorious from the east in 82 BC, marched a second time on Rome, and crushed the populares and their Italian allies at the Battle of the Colline Gate. He then revived the office of dictator, which had been inactive since the Second Punic War, over a century before. He used his powers to purge his opponents, and reform Roman constitutional laws, to restore the primacy of the Senate and limit the power of the tribunes of the plebs. Resigning his dictatorship in 79 BC, Sulla retired to private life and died the following year.

Sulla's military coup—ironically enabled by Marius' military reforms that bound the army's loyalty with the general rather than to the republic—permanently destabilized the Roman power structure. Later political leaders such as Julius Caesar would follow his precedent in attaining political power through force.[8]

Early years[]

Sulla, the son of Lucius Cornelius Sulla and the grandson of Publius Cornelius Sulla,[9] was born into a branch of the patrician gens Cornelia, but his family had fallen to an impoverished condition at the time of his birth. The reason behind this was because an ancestor, Publius Cornelius Rufinius, was banished from the Senate after having been caught possessing more than 10 pounds of silver plate.[10][11] As a result of this, Sulla's branch of the gens lost public standing and never retained the position of consul or dictator until Sulla came.[8] A story says that when he was a baby, his nurse was carrying him around the streets, until a strange woman walked up to her and said, "Puer tibi et reipublicae tuae felix." This can be translated as, "The boy will be a source of luck to you and your state."[12] Lacking ready money, Sulla spent his youth among Rome’s comedians, actors, lute players, and dancers. During these times on the stage, after initially singing, he started writing plays, Atellan farces, a kind of crude comedy.[13] He retained an attachment to the debauched nature of his youth until the end of his life; Plutarch mentions that during his last marriage – to Valeria – he still kept company with "actresses, musicians, and dancers, drinking with them on couches night and day."[14]

Sulla almost certainly received a good education. Sallust declares him well-read and intelligent, and he was fluent in Greek, which was a sign of education in Rome. The means by which Sulla attained the fortune, which later would enable him to ascend the ladder of Roman politics, the cursus honorum, are not clear, although Plutarch refers to two inheritances - one from his stepmother (who loved him dearly, as if he were her own son)[15] and the other from Nicopolis, a (possibly Greek) low-born woman who became rich.[16]

Capture of Jugurtha[]

The Jugurthine War had started in 112 BC when Jugurtha, grandson of Massinissa of Numidia, claimed the entire kingdom of Numidia, in defiance of Roman decrees that divided it among several members of the royal family.

Rome declared war on Jugurtha in 111 BC, but for five years, the Roman legions were unsuccessful. Several Roman commanders were bribed (Bestia and Spurius), and one (Aulus Postumius Albinus) was defeated. In 109, Rome sent Quintus Caecilius Metellus to continue the war. Gaius Marius, a lieutenant of Metellus, saw an opportunity to usurp his commander and fed rumors of incompetence and delay to the publicani (tax gatherers) in the region. These machinations caused calls for Metellus' removal; despite delaying tactics by Metellus, in 107 BC, Marius returned to Rome to stand for the consulship. Marius was elected consul and took over the campaign, while Sulla was nominated as quaestor to him.

Under Marius, the Roman forces followed a very similar plan as under Metellus and ultimately defeated the Numidians in 106 BC, due in large part to Sulla's initiative in capturing the Numidian king. He had persuaded Jugurtha's father-in-law, King Bocchus I of Mauretania (a nearby kingdom), to betray Jugurtha, who had fled to Mauretania for refuge. It was a dangerous operation, with King Bocchus weighing up the advantages of handing Jugurtha over to Sulla or Sulla over to Jugurtha.[17] The publicity attracted by this feat boosted Sulla's political career. A gilded equestrian statue of Sulla donated by King Bocchus was erected in the Forum to commemorate his accomplishment. Although Sulla had engineered this move, as Sulla was serving under Marius at the time, Marius took credit for this feat.

The Cimbri and the Teutones[]

In 104 BC, the Cimbri and the Teutones, two Germanic tribes who had bested the Roman legions on several occasions, seemed to be heading for Italy. As Marius, fresh from his victory over Jugurtha, was considered to be Rome's best military commander at that particular time, the Senate allowed him to lead the campaign against the northern invaders. Sulla, who had served under Marius during the Jugurthine War, joined his old commander as tribunus militum (military tribune). First, he helped Marius in recruiting and training legionaries; then, he led troops to subdue the Volcae Tectosages, and succeeded in capturing their leader Copillus. In 103, Sulla succeeded in persuading the Germanic Marsi tribe to become friends and allies of Rome; they detached themselves from the Germanic confederation and went back to Germania.

In 102, when Marius became consul for the fourth time, an unusual separation occurred between Marius and Sulla. For reasons unknown, Sulla requested a transfer to the army of Quintus Lutatius Catulus, Marius' consular partner. While Marius marched against the Teutones and Ambrones in Gaul, Catulus was tasked with keeping the Cimbri out of Italy. Catulus tasked Sulla with subduing the tribes in the north of Cisalpine Gaul to keep them from joining the Cimbri. Overconfident, Catulus tried to stop the Cimbri, but he was severely outnumbered and his army suffered some losses. Meanwhile, Marius had completely defeated the Ambrones and the Teutones at the Battle of Aquae Sextiae.

In 101, the armies of Marius and Catulus joined forces and faced the enemy tribes at the Battle of Vercellae. During the battle, Sulla commanded the cavalry on the right and was instrumental in achieving victory.[18] Sulla and his cavalry routed the barbarian cavalry and drove them into the main body of the Cimbri, causing chaos. Catulus, seeing an opportunity, threw his men forward and followed up on Sulla's successful action. By noon, the warriors of the Cimbri were defeated. Victorious at Vercellae, Marius and Catulus were both granted triumphs as the co-commanding generals. Sulla's role in the Vercellae victory was also hard to ignore, and formed the launchpad for his political career.

Cilician governorship[]

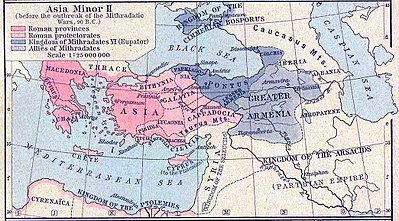

Returning to Rome, Sulla was elected praetor urbanus for 97 BC.[19] In 96 BC, he was appointed propraetor of the province of Cilicia in Asia Minor. A serious problem had arisen with pirates there, and he was commonly assumed to have been sent there to deal with them.[20]

While governing Cilicia, Sulla received orders from the Senate to restore King Ariobarzanes to the throne of Cappadocia. Ariobarzanes had been driven out by Mithridates VI of Pontus, who wanted to install one of his own sons (Ariarathes) on the Cappadocian throne. Despite initial difficulties, Sulla succeeded in restoring Ariobarzanes to the throne. The Romans among his troops were sufficiently impressed by his leadership that they hailed him imperator on the field.[21]

Sulla's campaign in Cappadocia had led him to the banks of the Euphrates, where he was approached by an embassy from the Parthian Empire. Sulla was the first Roman magistrate to meet a Parthian ambassador. At the meeting, he took the seat between the Parthian ambassador, Orobazus, and King Ariobarzanes, hereby, perhaps unintentionally, slighting the Parthian king by portraying the Parthians and the Cappadocians as equals and himself and Rome as superior. The Parthian ambassador, Orobazus, was executed upon his return to Parthia for allowing this humiliation. At this meeting, Sulla was told by a Chaldean seer that he would die at the height of his fame and fortune. This prophecy was to have a powerful hold on Sulla throughout his lifetime.[22][23]

In 94 BC, Sulla repulsed the forces of Tigranes the Great of Armenia from Cappadocia.[24] In 93 BC, Sulla left the east and returned to Rome, where he aligned himself with the optimates, in opposition to Gaius Marius. Sulla was regarded to have done well in the east - restoring Ariobarzanes to the throne, being hailed imperator on the field by his men, and being the first Roman to make a treaty with the Parthians.[25]

Social War[]

The Social War resulted from Rome's intransigence regarding the civil liberties of the Socii, Rome's Italian allies. The Socii (such as the Samnites) had been enemies of Rome, but had eventually submitted, whereas the Latins were confederates of longer standing. As a result, the Latins were given more respect and better treatment.[26] Subjects of the Roman Republic, these Italian provincials could be called to arms in its defense or could be subjected to extraordinary taxes, but they had no say in the expenditure of these taxes or in the uses of the armies that might be raised in their territories. The Social War was, in part, caused by the continued rebuttal of those who sought to extend Roman citizenship to the Socii. The Gracchi, Tiberius and Gaius, were successively killed by optimate supporters who sought to maintain the status quo. The assassination of Marcus Livius Drusus the Younger, a tribune, whose reforms were intended not only to strengthen the position of the Senate, but also to grant Roman citizenship to the allies, greatly angered the Socii. In consequence, most allied against Rome, leading to the outbreak of the Social War.

At the beginning of the Social War, the Roman aristocracy and Senate were beginning to fear Gaius Marius' ambition, which had already given him six consulships (including five in a row, from 104 to 100 BC). They were determined that he should not have overall command of the war in Italy. In this last rebellion of the Italian allies, Sulla outshone both Marius and the consul Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo (the father of Pompey).

Serving under Lucius Caesar (90 BC)[]

Sulla first served under the consul of 90, Lucius Julius Caesar, and fought against the southern group of the Italian rebels (the Samnites) and their allies. Sulla and Caesar defeated Gaius Papius Mutilus, one of the leaders of the Samnites, at Acerrae. Then, commanding one of Caesar's divisions and working in tandem with his old commander Marius, Sulla defeated an army of the Marsi and the Marruncini. Together, they killed 6,000 rebels, as well as the Marruncini general Herius Asinus.[27][28] When Lucius Caesar returned to Rome, he ordered Sulla to reorganize the legions for deployment next year.[29]

In sole command (89 BC)[]

In 89 BC, now a praetor, Sulla served under the consul Lucius Porcius Cato Licinianus. Cato got himself killed early on while storming a rebel camp.[30] Sulla, being an experienced military man, took command of Rome's southern army, and continued the fight against the Samnites and their allies. He besieged the rebel cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum. The admiral in command of the fleet blockading Pompeii, Aulus Postumius Albinus, offended his troops, which caused them to stone him to death. When news of this reached Sulla, he declined to punish the murderers, because he needed the men and he figured Albinus had brought it on himself.[31] During the siege of Pompeii, rebel reinforcements under the command of a general called Lucius Cleuntius arrived.[32][33] Sulla drove off Cleuntius and his men, and pursued them all the way to the city of Nola, a town to the northeast of Pompeii.[32] At Nola, a terrible battle ensued; Cleuntius' troops were desperate and fought savagely, but Sulla's army killed them almost to the last man, with 20,000 rebels dying in front of the city walls.[32] Sulla is said to have killed Cleuntius with his own hands. The men who had fought with Sulla at the battle before the walls of Nola hailed him imperator on the field, and also awarded him the Grass Crown, or Corona Graminea.[32] This was the highest Roman military honor, awarded for personal bravery to a commander who saves a Roman legion or army in the field. Unlike other Roman military honors, it was awarded by acclamation of the soldiers of the rescued army, and consequently, very few were ever awarded. The crown, by tradition, was woven from grasses and other plants taken from the actual battlefield.[34] Sulla then returned to the siege of Pompeii. After taking Pompeii and Herculaneum, Sulla captured Aeclanum, the chief town of the Hirpini (he did this by setting the wooden breastworks on fire).[35][36]

After forcing the capitulation of all the rebel-held cities in Campania, with the exception of Nola, Sulla launched a dagger thrust into the heartland of the Samnites. He was able to ambush a Samnite army in a mountain pass (in a reversal of the Battle of the Caudine Forks) and then, having routed them, he marched on the rebel capital, storming it in a brutal, three-hour assault. Although Nola remained defiant, along with a few other pockets of resistance, Sulla had effectively finished the rebellion in the south for good.[37][38]

Consul of Rome (88 BC)[]

As a result of his success in bringing the Social War to a successful conclusion, he was elected consul for the first time in 88 BC, with Quintus Pompeius Rufus (soon his daughter's father-in-law) as his colleague. Sulla was 50 years old by then (most Roman consuls being in their early 40s), and only then had he finally achieved his rise into Rome's ruling class. He also married his third wife, Caecilia Metella, which connected him to the mighty Caecilii Metelli family.[39]

Sulla started his consulship by passing two laws designed to regulate Rome's finances, which were in a very sorry state after all the years of continual warfare. The first of the leges Corneliae concerned the interest rates, and stipulated that all debtors were to pay simple interest only, rather than the common compound interest that so easily bankrupted the debtors. The interest rates were also to be agreed between both parties at the time that the loan was made, and should stand for the whole term of the debt, without further increase.[40]

The second law concerned the sponsio, which was the sum in dispute in cases of debt, and usually had to be lodged with the praetor before the case was heard. This, of course, meant that many cases were never heard at all, as poorer clients did not have the money for the sponsio. Sulla's law waived the sponsio, allowing such cases to be heard without it. This, of course, made him very popular with the poorer citizens.[40]

After passing his laws, Sulla temporarily left Rome to attend to the cleaning-up of the Italian allies, especially Nola, which was still holding out. While Sulla was besieging Nola, his political opponents were moving against him in Rome.[41]

First march on Rome[]

As senior consul, Sulla had been allocated the command of the First Mithridatic War against King Mithridates VI of Pontus.[42][43][44] This war against Mithridates promised to be a very prestigious and also a very lucrative affair.[43] Marius, Sulla's old commander, also ran for the command, but Sulla was fresh from his victories in Campania and Samnium, and almost 20 years younger (50 vs. Marius' 69), so Sulla was confirmed in the command against the Pontic king.[42] Before he left Rome, Sulla passed two laws (the first of the leges Corneliae) and then went south, into Campania, to take care of the last Italian rebels.[41][45][46] Before leaving, Sulla and his consular colleague Quintus Pompeius Rufus blocked the legislation of the tribune Publius Sulpicius Rufus, meant to ensure the rapid organization of the Italian allies into Roman citizenship.[47][43][44] Sulpicius found an ally in Marius, who said he would support the bill, at which point Sulpicius felt confident enough to tell his supporters to start a riot.

Sulla was besieging Nola when he heard that rioting had broken out in Rome. He quickly returned to Rome to meet with Pompeius Rufus; however, Sulpicius' followers attacked the meeting, forcing Sulla to take refuge in Marius' house, who in turn forced him to support Sulpicius' pro-Italian legislation in exchange for protection from the mob.[48][49][50] Sulla's son-in-law (Pompeius Rufus' son) was killed in the midst of these violent riots.[48] After leaving Rome again for Nola, Sulpicius (who was given a promise from Marius to wipe out his enormous debts) called an assembly of the people to reverse the Senate's previous decision to grant Sulla military command, and instead transfer it to Marius.[48] Sulpicius also used the assembly to forcefully eject senators from the Senate until not enough of them were present to form a quorum. Violence in the Forum ensued, and some nobles tried to lynch Sulpicius (as had been done to the brothers Gracchi, and to Saturninus), but failed in the face of his bodyguard of gladiators.

Sulla received news of this new turmoil while at his camp at Nola, surrounded by his Social War veterans, the men whom he had personally led to victory, who had hailed him imperator and who had awarded him the Grass Crown.[51][52][53] His soldiers stoned envoys of the assemblies who came to announce that the command of the Mithridatic War had been transferred to Marius. Sulla then took five of the six legions stationed at Nola and marched on Rome. This was an unprecedented event, as no general before him had ever crossed the city limits, the pomerium, with his army. Most of his commanders (with the exception of his kinsman through marriage, Lucullus), though, refused to accompany him. Sulla justified his actions on the grounds that the Senate had been neutered; the mos maiorum ("the way of the elders"/"the traditional way", which amounted to a Roman constitution, though none of it was codified as such) had been offended by the Senate's negation of the rights of the year's consuls to fight the year's wars. Even the armed gladiators were unable to resist the organized Roman soldiers, and although Marius offered freedom to any slave who would fight with him against Sulla (an offer which Plutarch says only three slaves accepted),[54] his followers and he were forced to flee the city.[55][56]

Sulla consolidated his position, declared Marius and his allies hostes (enemies of the state), and addressed the Senate in a harsh tone, portraying himself as a victim, presumably to justify his violent entrance into the city. After restructuring the city's politics and strengthening the Senate's power, Sulla once more returned to his military camp and proceeded with the original plan of fighting Mithridates in Pontus.

Sulpicius was later betrayed and killed by one of his slaves, whom Sulla subsequently freed and then executed (being freed for giving the information leading to Sulpicius, but sentenced to death for betraying his master). Marius, however, fled to safety in Africa until he heard Sulla was once again out of Rome, when he began plotting his return. During his period of exile, Marius became determined that he would hold a seventh consulship, as foretold by the Sibyl decades earlier. By the end of 87 BC, Marius returned to Rome with the support of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, and in Sulla's absence, took control of the city. Marius declared Sulla's reforms and laws invalid, and officially exiled him. Marius and Cinna were elected consuls for the year 86 BC, but Marius died a fortnight later, thus Cinna was left in sole control of Rome.

First Mithridatic War[]

This section does not cite any sources. (June 2018) |

In the spring of 87 BC, Sulla landed at Dyrrhachium, in Illyria, at the head of five veteran legions.[57][58] Asia was occupied by the forces of Mithridates under the command of Archelaus. Sulla’s first target was Athens, ruled by a Mithridatic puppet, the tyrant Aristion. Sulla moved southeast, picking up supplies and reinforcements as he went. Sulla's chief of staff was Lucullus, who went ahead of him to scout the way and negotiate with Bruttius Sura, the existing Roman commander in Greece. After speaking with Lucullus, Sura handed over the command of his troops to Sulla. At Chaeronea, ambassadors from all the major cities of Greece (except Athens) met with Sulla, who impressed on them Rome's determination to drive Mithridates from Greece and the province of Asia. Sulla then advanced on Athens.

Sack of Athens[]

On arrival, Sulla threw up siegeworks encompassing not only Athens, but also the port of Piraeus. At the time, Archelaus had command of the sea, so Sulla sent Lucullus to raise a fleet from the remaining Roman allies in the eastern Mediterranean. His first objective was Piraeus, as Athens could not be resupplied without it. Huge earthworks were raised, isolating Athens and its port from the landside. Sulla needed wood, so he cut down everything, including the sacred groves of Greece, up to 100 miles from Athens. When more money was needed, he took from temples and sibyls alike. The currency minted from this treasure was to remain in circulation for centuries and was prized for its quality.

Despite the complete encirclement of Athens and its port, and several attempts by Archelaus to raise the siege, a stalemate seemed to have developed. Sulla, however, patiently bided his time. Soon, Sulla's camp was to fill with refugees from Rome, fleeing the massacres of Marius and Cinna. These also included his wife and children, as well as those of the optimate faction who had not been killed. Athens by now was starving, and grain was at famine levels in price. Inside the city, the population was reduced to eating shoe leather and grass. A delegation from Athens was sent to treat with Sulla, but instead of serious negotiations, they expounded on the glory of their city. Sulla sent them away, saying, "I was sent to Athens not to take lessons, but to reduce rebels to obedience."

His spies then informed him that Aristion was neglecting the Heptachalcum (part of the city wall), and Sulla immediately sent sappers to undermine the wall. About 900 feet of wall were brought down between the Sacred and Piraeic gates on the southwest side of the city. A midnight sack of Athens began, and after the taunts of Aristion, Sulla was not in a mood to be magnanimous. Blood was said to have literally flowed in the streets;[59] only after the entreaties of a few of his Greek friends (Midias and Calliphon) and the pleas of the Roman senators in his camp did Sulla decide enough was enough.[citation needed] He then concentrated his forces on the port of Piraeus, and Archelaus, seeing his hopeless situation, withdrew to the citadel and then abandoned the port to join up with his forces under the command of Taxiles. Sulla, as of yet not having a fleet, was powerless to prevent Archelaus' escape. Before leaving Athens, he burned the port to the ground. Sulla then advanced into Boeotia to take on Archelaus' armies and remove them from Greece.

Battle of Chaeronea[]

Sulla lost no time in intercepting the Pontic army, occupying a hill called Philoboetus that branched off mount Parnassus, overlooking the Elatean plain, with plentiful supplies of wood and water. The army of Archelaus, presently commanded by Taxiles, had to approach from the north and proceed along the valley towards Chaeronea. Over 120,000 men strong, it outnumbered Sulla's forces by at least three to one. Archelaus was in favor of a policy of attrition with the Roman forces, but Taxiles had orders from Mithridates to attack at once. Sulla got his men digging and occupied the ruined city of Parapotamii, which was impregnable and commanded the fords on the road to Chaeronea. He then made a move that looked to Archelaus like a retreat, abandoning the fords and moving in behind an entrenched palisade. Behind the palisade was the field artillery from the siege of Athens.

Archelaus advanced across the fords and tried to outflank Sulla’s men, only to have his right wing hurled back, causing great confusion in the Pontic army. Archelaus’ chariots then charged the Roman center, only to be destroyed on the palisades. Next came the phalanges, but they too found the palisades impassable, and received withering fire from the Roman field artillery. Then, Archelaus flung his right wing at the Roman left; Sulla, seeing the danger of this maneuver, raced over from the Roman right wing to help. Sulla stabilized the situation, at which point Archelaus flung in more troops from his right flank. This destabilized the Pontic army, slewing it towards its right flank. Sulla dashed back to his own right wing and ordered the general advance. The legions, supported by cavalry, dashed forward, and Archelaus’ army folded in on itself, like closing a pack of cards. The slaughter was terrible, and some reports estimate that only 10,000 men of Mithridates' original army survived. Sulla had defeated a vastly superior force in terms of numbers.

[]

The government of Rome (under the de facto rule of Cinna) then sent out Valerius Flaccus with an army to relieve Sulla of command in the east; Flaccus' second in command was Flavius Fimbria, who had few virtues. The two Roman armies camped next to each other, and Sulla, not for the first time, encouraged his soldiers to spread dissention among Flaccus' army. Many deserted to Sulla before Flaccus packed up and moved on north to threaten Mithridates' northern dominions. Meanwhile, Archelaus had been reinforced by 80,000 men brought over from Asia Minor by Dorylaeus, another of Mithridates' generals, and was embarking his army from his base on Euboea. The return of a large Mithridatic army caused a revolt of Boeotians against the Romans, and Sulla immediately marched his army back south.[60]

He chose the site of the battle to come — Orchomenus, a town in Boeotia that allowed a smaller army to meet a much larger one, due to its natural defenses, and was ideal terrain for Sulla's innovative use of entrenchment. This time, the Pontic army was in excess of 150,000, and it encamped itself in front of the busy Roman army, next to a large lake. It soon dawned on Archelaus what Sulla was up to; Sulla had not only been digging trenches, but also dikes, and he had the Pontic army in deep trouble before long. Desperate sallies by the Pontic forces were repulsed by the Romans, and the dikes moved onward.

On the second day, Archelaus made a determined effort to escape Sulla’s web of dikes; the entire Pontic army was hurled at the Romans, but the Roman legionaries were pressed together so tightly that their short swords were like an impenetrable barrier, through which the enemy could not escape. The battle turned into a rout, with slaughter on an immense scale. Plutarch notes that, 200 years later, armor and weapons from the battle were still being found. The battle of Orchomenus was another of the world's decisive battles, determining that the fate of Asia Minor would lay with Rome and its successors for the next millennium.

Sulla's victory and settlement[]

In 86 BC, after Sulla's victory in Orchomenos, he initially spent some time re-establishing Roman authority. His legatus soon arrived with the fleet he was sent to gather, and Sulla was ready to recapture lost Greek islands before crossing into Asia Minor. The second Roman army under the command of Flaccus, meanwhile, moved through Macedonia and into Asia Minor. After the capture of Philippi, the remaining Mithridatic forces crossed the Hellespont to get away from the Romans. Fimbria encouraged his forces to loot and create general havoc as they went. Flaccus was a fairly strict disciplinarian, and the behavior of his lieutenant led to discord between the two.

At some point, as this army crossed the Hellespont to pursue Mithridates' forces, Fimbria seems to have started a rebellion against Flaccus. While seemingly minor enough to not cause immediate repercussions in the field, Fimbria was relieved of his duty and ordered back to Rome. The return trip included a stop at the port city of Byzantium, though, and here, rather than continuing towards home, Fimbria took command of the garrison. Flaccus, hearing of this, marched his army to Byzantium to put a stop to the rebellion, but walked right into his own undoing. The army preferred Fimbria (not surprisingly, considering his leniency in regard to plundering) and a general revolt ensued. Flaccus attempted to flee, but was captured and executed shortly afterwards. With Flaccus out of the way, Fimbria took complete command.

The following year (85 BC), Fimbria took the fight to Mithridates, while Sulla continued to operate in the Aegean. Fimbria quickly won a decisive victory over the remaining Mithridatic forces and moved on the capital of Pergamum. With all vestige of hope crumbling for Mithridates, he fled Pergamum to the coastal city of Pitane. Fimbria, in pursuit, laid siege to the town, but had no fleet to prevent Mithridates' escape by sea. Fimbria called upon Sulla's legate, Lucullus, to bring his fleet around to blockade Mithridates, but Sulla seemingly had other plans.

Sulla apparently had been in private negotiation with Mithridates to end the war. He wanted to develop easy terms and get the ordeal over as quickly as possible. The quicker it was dealt with, the faster he would be able to settle political matters in Rome. With this in mind, Lucullus and his navy refused to help Fimbria, and Mithridates "escaped" to Lesbos. Later, at Dardanus, Sulla and Mithridates met personally to negotiate terms. With Fimbria re-establishing Roman hegemony over the cities of Asia Minor, Mithridates' position was completely untenable, yet Sulla, with his eyes on Rome, offered uncharacteristically mild terms. Mithridates was forced to give up all his conquests (which Sulla and Fimbria had already managed to take back by force), surrender any Roman prisoners, provide a 70-ship fleet to Sulla along with supplies, and pay a tribute of 2,000 to 3,000 gold talents. In exchange, Mithridates was able to keep his original kingdom and territory and regain his title of "friend of the Roman people".

Things in the east, though, were not settled yet. Fimbria was enjoying free rein in the province of Asia, and led a cruel oppression of both those who were involved against the Romans and those who were now in support of Sulla. Unable to leave a potentially dangerous army in his rear, Sulla crossed into Asia. He pursued Fimbria to his camp at Thyatira, where Fimbria was confident in his ability to repulse an attack. Fimbria, however, soon found that his men wanted nothing to do with opposing Sulla, and many deserted or refused to fight in the coming battle. Sensing all was lost, Fimbria took his own life, while his army went over to Sulla.

To ensure the loyalty of both Fimbria's troops and his own veterans, who were not happy about the easy treatment of their enemy, Mithridates, Sulla now started to penalize the province of Asia. His veterans were scattered throughout the province and allowed to extort the wealth of local communities. Large fines were placed on the province for lost taxes during their rebellion and the cost of the war.

As 84 BC began, Cinna, still consul in Rome, was faced with minor disturbances among Illyrian tribes. Perhaps in an attempt to gain experience for an army to act as a counter to Sulla's forces, or to show Sulla that the Senate also had some strength of its own, Cinna raised an army to deal with this Illyrian problem. Conveniently, the source of the disturbance was located directly between Sulla and another march on Rome. Cinna pushed his men hard to move to position in Illyria, and forced marches through snow-covered mountains did little to endear Cinna to his army. A short time after departing Rome, Cinna was stoned to death by his own men. Hearing of Cinna's death, and the ensuing power gap in Rome, Sulla gathered his forces and prepared for a second march on the capital.

Second march on Rome[]

In 83 BC, Sulla prepared his five legions and left the two originally under Fimbria to maintain peace in Asia Minor. In the spring of that year, Sulla crossed the Adriatic with a large fleet from Patrae, west of Corinth, to Brundisium and Tarentum in the heel of Italy.[61][62] Landing uncontested, he had ample opportunity to prepare for the coming war.

In Rome, the newly elected consuls, Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus (Asiagenus) and Gaius Norbanus, levied and prepared armies of their own to stop Sulla and protect the Republican government. Norbanus marched first, with the intention of blocking Sulla's advance at Canusium. Seriously defeated, Norbanus was forced to retreat to Capua, where no respite remained. Sulla followed his defeated adversary and won another victory in a very short time. Meanwhile, Asiagenus was also on the march south with an army of his own, but neither Asiagenus nor his army seemed to have any motivation to fight. At the town of Teanum Sidicinum, Sulla and Asiagenus met face-to-face to negotiate, and Asiagenus surrendered without a fight. The army sent to stop Sulla wavered in the face of battle against experienced veterans, and certainly along with the prodding of Sulla's operatives, gave up the cause, going over to Sulla's side as a result. Left without an army, Asiagenus had little choice but to cooperate, and later writings of Cicero suggest that the two men actually discussed many matters, regarding Roman government and the constitution.

Sulla let Asiagenus leave the camp, firmly believing him to be a supporter. He was possibly expected to deliver terms to the Senate, but immediately rescinded any thought of supporting Sulla upon being set free. Sulla later made publicly known the fact that not only would Asiagenus suffer for opposing him, but also that any man who continued to oppose him after this betrayal would suffer bitter consequences. With Sulla's three quick victories, though, the situation began to rapidly turn in his favor. Many of those in a position of power, who had not yet taken a clear side, now chose to support Sulla. The first of these was the governor of Africa, Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, who was an old enemy of Marius and Cinna's; he led an open revolt against the Marian forces in Africa, with additional help coming from Picenum and Spain. Additionally, two of the three future triumviri joined Sulla's cause in his bid to take control. Marcus Licinius Crassus marched with an army from Spain, and would later play a pivotal role at the Colline Gate. The young son of Pompeius Strabo (the butcher of Asculum during the Social War), Pompey, raised an army of his own from among his father's veterans, and threw his lot in with Sulla. At the age of 23, and never having held a senatorial office, Pompey forced himself into the political scene with an army at his back.

Regardless, the war continued, with Asiagenus raising another army in defense. This time, he moved after Pompey, but once again, his army abandoned him and went over to the enemy. As a result, desperation followed in Rome as 83 BC came to a close. Cinna's old co-consul, Papirius Carbo, and Gaius Marius the Younger, the 26-year-old son of the dead consul, were elected as consuls. Hoping to inspire Marian supporters throughout the Roman world, recruiting began in earnest among the Italian tribes who had always been loyal to Marius. In addition, possible Sullan supporters were murdered. The urban praetor Lucius Junius Brutus Damasippus led a slaughter of those senators who seemed to lean towards the invading forces, yet one more incident of murder in a growing spiral of violence as a political tool in the late Republic.

As the campaign year of 82 BC opened, Carbo took his forces to the north to oppose Pompey, while Marius moved against Sulla in the south. Attempts to defeat Pompey failed, and Metellus with his African forces, along with Pompey, secured northern Italy for Sulla. In the south, young Marius gathered a large host of Samnites, who assuredly would lose influence with the antipopular Sulla in charge of Rome. Marius met Sulla at Sacriportus, and the two forces engaged in a long and desperate battle. In the end, many of Marius' men switched sides over to Sulla, and Marius had no choice but to retreat to Praeneste. Sulla followed the son of his arch rival and laid siege to the town, leaving a subordinate in command. Sulla himself moved north to push Carbo, who had withdrawn to Etruria to stand between Rome and the forces of Pompey and Metellus.

Indecisive battles were fought between Carbo and Sulla's forces, but Carbo knew that his cause was lost. News arrived of a defeat by Norbanus in Gaul, and that he also switched sides to Sulla. Carbo, caught between three enemy armies and with no hope of relief, fled to Africa. This was not yet the end of the resistance, however, as the remaining Marian forces gathered together and attempted several times to relieve young Marius at Praeneste. A Samnite force under Pontius Telesinus joined in the relief effort, but the combined armies were still unable to break Sulla. Rather than continue trying to rescue Marius, Telesinus moved north to threaten Rome.

On November 1 82 BC, the two forces met at the Battle of the Colline Gate, just outside Rome. The battle was a huge and desperate final struggle, with both sides certainly believing their own victory would save Rome. Sulla was pushed hard on his left flank, with the situation so dangerous that his men and he were pushed right up against the city walls. Crassus' forces, however, fighting on Sulla's right wing, managed to turn the opposition's flank and drive them back. The Samnites and the Marian forces were folded up, and then broke. In the end, over 50,000 combatants lost their lives, and Sulla stood alone as the master of Rome.

Dictatorship and constitutional reforms[]

At the end of 82 BC or the beginning of 81 BC,[63] the Senate appointed Sulla dictator legibus faciendis et reipublicae constituendae causa ("dictator for the making of laws and for the settling of the constitution"). The assembly of the people subsequently ratified the decision, with no limit set on his time in office. Sulla had total control of the city and Republic of Rome, except for Hispania (which Marius' general Quintus Sertorius had established as an independent state). This unusual appointment (used hitherto only in times of extreme danger to the city, such as during the Second Punic War, and then only for 6-month periods) represented an exception to Rome's policy of not giving total power to a single individual. Sulla can be seen as setting the precedent for Julius Caesar's dictatorship, and for the eventual end of the Republic under Augustus.

In total control of the city and its affairs, Sulla instituted a series of proscriptions (a program of executing those whom he perceived as enemies of the state and confiscating their property). Plutarch states in his Life of Sulla that "Sulla now began to make blood flow, and he filled the city with deaths without number or limit," further alleging that many of the murdered victims had nothing to do with Sulla, though Sulla killed them to "please his adherents."

Sulla immediately proscribed 80 persons without communicating with any magistrate. As this caused a general murmur, he let one day pass, and then proscribed 220 more, and again on the third day as many. In an harangue to the people, he said, with reference to these measures, that he had proscribed all he could think of, and as to those who now escaped his memory, he would proscribe them at some future time.

The proscriptions are widely perceived as a response to similar killings that Marius and Cinna had implemented while they controlled the Republic during Sulla's absence. Proscribing or outlawing every one of those whom he perceived to have acted against the best interests of the Republic while he was in the east, Sulla ordered some 1,500 nobles (i.e. senators and equites) executed, although as many as 9,000 people were estimated to have been killed.[64] The purge went on for several months. Helping or sheltering a proscribed person was punishable by death, while killing a proscribed person was rewarded with two talents. Family members of the proscribed were not excluded from punishment, and slaves were not excluded from rewards. As a result, "husbands were butchered in the arms of their wives, sons in the arms of their mothers."[65] The majority of the proscribed had not been enemies of Sulla, but instead were killed for their property, which was confiscated and auctioned off. The proceeds from auctioned property more than made up for the cost of rewarding those who killed the proscribed, filling the treasury. Possibly to protect himself from future political retribution, Sulla had the sons and grandsons of the proscribed banned from running for political office, a restriction not removed for over 30 years.

The young Gaius Julius Caesar, as Cinna's son-in-law, became one of Sulla's targets, and fled the city. He was saved through the efforts of his relatives, many of whom were Sulla's supporters, but Sulla noted in his memoirs that he regretted sparing Caesar's life, because of the young man's notorious ambition. Historian Suetonius records that when agreeing to spare Caesar, Sulla warned those who were pleading his case that he would become a danger to them in the future, saying, "In this Caesar, there are many Mariuses."[66][67]

Sulla, who opposed the Gracchian popularis reforms, was an optimate; though his coming to the side of the traditional Senate originally could be described as atavistic when dealing with the tribunate and legislative bodies, while more visionary when reforming the court system, governorships, and membership of the Senate.[68] As such, he sought to strengthen the aristocracy, and thus the Senate.[68] Sulla retained his earlier reforms, which required senatorial approval before any bill could be submitted to the Plebeian Council (the principal popular assembly), and which had also restored the older, more aristocratic "Servian" organization to the Centuriate Assembly (assembly of soldiers).[69] Sulla, himself a patrician, thus ineligible for election to the office of Plebeian Tribune, thoroughly disliked the office. As Sulla viewed the office, the tribunate was especially dangerous, and his intention was to not only deprive the Tribunate of power, but also of prestige (Sulla himself had been officially deprived of his eastern command through the underhanded activities of a tribune). Over the previous 300 years, the tribunes had directly challenged the patrician class and attempted to deprive it of power in favor of the plebeian class. Through Sulla's reforms to the Plebeian Council, tribunes lost the power to initiate legislation. Sulla then prohibited ex-tribunes from ever holding any other office, so ambitious individuals would no longer seek election to the tribunate, since such an election would end their political career.[70] Finally, Sulla revoked the power of the tribunes to veto acts of the Senate, although he left intact the tribunes' power to protect individual Roman citizens.

Sulla then increased the number of magistrates elected in any given year,[68] and required that all newly elected quaestores gain automatic membership in the Senate. These two reforms were enacted primarily to allow Sulla to increase the size of the Senate from 300 to 600 senators. This also removed the need for the censor to draw up a list of senators, since more than enough former magistrates were always available to fill the Senate.[68] To further solidify the prestige and authority of the Senate, Sulla transferred the control of the courts from the equites, who had held control since the Gracchi reforms, to the senators. This, along with the increase in the number of courts, further added to the power that was already held by the senators.[70] Sulla also codified, and thus established definitively, the cursus honorum,[70] which required an individual to reach a certain age and level of experience before running for any particular office. Sulla also wanted to reduce the risk that a future general might attempt to seize power, as he himself had done. To this end, he reaffirmed the requirement that any individual wait for 10 years before being re-elected to any office. Sulla then established a system where all consuls and praetors served in Rome during their year in office, and then commanded a provincial army as a governor for the year after they left office.[70]

Finally, in a demonstration of his absolute power, Sulla expanded the Pomerium, the sacred boundary of Rome, unchanged since the time of the kings.[71] Sulla's reforms both looked to the past (often repassing former laws) and regulated for the future, particularly in his redefinition of maiestas (treason) laws and in his reform of the Senate.

After a second consulship in 80 BC (with Metellus Pius), Sulla, true to his traditionalist sentiments, resigned his dictatorship in early 79,[6] disbanded his legions, and re-established normal consular government. He dismissed his lictores and walked unguarded in the Forum, offering to give account of his actions to any citizen.[72][11] In a manner that the historian Suetonius thought arrogant, Julius Caesar later mocked Sulla for resigning the dictatorship.[73]

Retirement and death[]

As promised, when his tasks were complete, Sulla returned his powers and withdrew to his country villa near Puteoli to be with his family. Plutarch states in his Life of Sulla that he retired to a life spent in dissolute luxuries, and he "consorted with actresses, harpists, and theatrical people, drinking with them on couches all day long." From this distance, Sulla remained out of the day-to-day political activities in Rome, intervening only a few times when his policies were involved (e.g. the execution of Granius, shortly before his own death).[74][75]

Sulla's goal now was to write his memoirs, which he finished in 78 BC, just before his death. They are now largely lost, although fragments from them exist as quotations in later writers. Ancient accounts of Sulla's death indicate that he died from liver failure or a ruptured gastric ulcer (symptomized by a sudden hemorrhage from his mouth, followed by a fever from which he never recovered), possibly caused by chronic alcohol abuse.[76][75][77][78][79] Accounts were also written that he had an infestation of worms, caused by the ulcers, which led to his death.[80]

His public funeral in Rome (in the Forum, in the presence of the whole city) was on a scale unmatched until that of Augustus in AD 14. Sulla's body was brought into the city on a golden bier, escorted by his veteran soldiers, and funeral orations were delivered by several eminent senators, with the main oration possibly delivered by Lucius Marcius Philippus or Hortensius. Sulla's body was cremated and his ashes placed in his tomb in the Campus Martius.[81] An epitaph, which Sulla composed himself, was inscribed onto the tomb, reading, "No friend ever served me, and no enemy ever wronged me, whom I have not repaid in full."[82] Plutarch claims he had seen Sulla's personal motto carved on his tomb on the Campus Martius. The personal motto was "no better friend, no worse enemy."[83]

Legacy[]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2016) |

Sulla is generally seen as having set the precedent for Caesar's march on Rome and dictatorship. Cicero comments that Pompey once said, "If Sulla could, why can't I?"[84][85] Sulla's example proved that it could be done, therefore inspiring others to attempt it; in this respect, he has been seen as another step in the Republic's fall. Further, Sulla failed to frame a settlement whereby the army (following the Marian reforms allowing nonland-owning soldiery) remained loyal to the Senate, rather than to generals such as himself. He attempted to mitigate this by passing laws to limit the actions of generals in their provinces, and although these laws remained in effect well into the imperial period, they did not prevent determined generals, such as Pompey and Julius Caesar, from using their armies for personal ambition against the Senate, a danger of which Sulla was intimately aware.

While Sulla's laws such as those concerning qualification for admittance to the Senate, reform of the legal system and regulations of governorships remained on Rome's statutes long into the principate, much of his legislation was repealed less than a decade after his death. The veto power of the tribunes and their legislating authority were soon reinstated, ironically during the consulships of Pompey and Crassus.[86]

Sulla's descendants continued to be prominent in Roman politics into the imperial period. His son, Faustus Cornelius Sulla, issued denarii bearing the name of the dictator,[87] as did a grandson, Quintus Pompeius Rufus. His descendants among the Cornelii Sullae would hold four consulships during the imperial period: Lucius Cornelius Sulla in 5 BC, Faustus Cornelius Sulla in AD 31, Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix in AD 33, and Faustus Cornelius Sulla Felix (the son of the consul of 31) in AD 52. The latter was the husband of Claudia Antonia, daughter of the emperor Claudius. His execution in AD 62 on the orders of emperor Nero made him the last of the Cornelii Sullae.

His rival, Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, described Sulla as having the cunning of a fox and the courage of a lion – but that it was the former attribute that was by far the most dangerous. This mixture was later referred to by Machiavelli in his description of the ideal characteristics of a ruler.[88]

Cultural references[]

- The dictator is the subject of four Italian operas, two of which take considerable liberties with history: Lucio Silla by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and Silla by George Frideric Handel. In each, he is portrayed as a bloody, womanizing, ruthless tyrant who eventually repents his ways and steps down from the throne of Rome. Pasquale Anfossi and Johann Christian Bach also wrote operas on this subject.

- Sulla is a central character in the first three Masters of Rome novels, by Colleen McCullough. Sulla is depicted as ruthless and amoral, very self-assured, and personally brave and charming, especially with women. His charm and ruthlessness make him a valuable aide to Gaius Marius. Sulla’s desire to move out of the shadow of aging Marius eventually leads to civil war. Sulla softened considerably after the birth of his son, and was devastated when the boy died at a young age. The novels depict Sulla full of regrets about having to put aside his homosexual relationship with a Greek actor to take up his public career.

- Sulla is played by Richard Harris in the 2002 miniseries Julius Caesar.

- Lucius Cornelius Sulla is also a character in the first book of the Emperor novels by Conn Iggulden, which are centered around the lives of Gaius Julius Caesar and Marcus Junius Brutus.

- Sulla is a major character in Roman Blood, the first of the Roma Sub Rosa mystery novels by Steven Saylor.

- Sulla is the subject of The Sword of Pleasure, a novel by Peter Green published in the UK in 1957. The novel is in the form of an autobiography.

Marriages and children[]

- His first wife was Ilia, according to Plutarch. If Plutarch's text is to be amended to "Julia", then she is likely to have been one of the Julias related to Julius Caesar, most likely Julia Caesaris, Caesar's first cousin once removed.[89] They had two children:

- The first was Cornelia, who first married Quintus Pompeius Rufus the Younger and later Mamercus Aemilius Lepidus Livianus, giving birth to Pompeia (second wife of Julius Caesar) with the former.

- The second was Lucius Cornelius Sulla, who died young.

- His second wife was Aelia.

- His third wife was Cloelia, whom Sulla divorced due to sterility.

- His fourth wife was Caecilia Metella, with whom he also had two children:

- They had twins Faustus Cornelius Sulla, who was a quaestor in 54 BC, and Fausta Cornelia, who first married to Gaius Memmius (praetor in 58 BC), then later to Titus Annius Milo (praetor in 54 BC), giving birth to Gaius Memmius with the former, and was also a suffect consul in 34 BC.

- His fifth and last wife was Valeria, with whom he had only one child, Cornelia Postuma, who was born after Sulla's death.

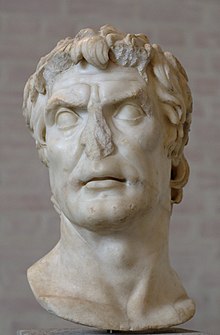

Appearance and character[]

Sulla was red-blond[90] and blue-eyed, and had a dead-white face covered with red marks.[91] Plutarch notes that Sulla considered that "his golden head of hair gave him a singular appearance."[92]

He was said to have a duality between being charming, easily approachable, and able to joke and cavort with the most simple of people, while also assuming a stern demeanor when he was leading armies and as dictator. An example of the extent of his charming side was that his soldiers would sing a ditty about Sulla's one testicle, although without truth, to which he allowed as being "fond of a jest."[93] This duality, or inconsistency, made him very unpredictable and "at the slightest pretext, he might have a man crucified, but, on another occasion, would make light of the most appalling crimes; or he might happily forgive the most unpardonable offenses, and then punish trivial, insignificant misdemeanors with death and confiscation of property."[94]

His excesses and penchant for debauchery could be attributed to the difficult circumstances of his youth, such as losing his father while he was still in his teens and retaining a doting stepmother, necessitating an independent streak from an early age. The circumstances of his relative poverty as a young man left him removed from his patrician brethren, enabling him to consort with revelers and experience the baser side of human nature. This "firsthand" understanding of human motivations and the ordinary Roman citizen may explain why he was able to succeed as a general despite lacking any significant military experience before his 30s.[95]

Chronology[]

- circa 138 BC: Born in Rome;

- 110 BC: Marries first wife;

- 107-105 BC: Quaestor and pro quaestore to Gaius Marius in the war with Jugurtha in Numidia;

- 106 BC: End of Jugurthine War;

- 104 BC: Legatus to Marius (serving his second consulship) in Gallia Transalpina;

- 103 BC: Tribunus militum in the army of Marius (serving his third consulship) in Gallia Transalpina;

- 102-101 BC: Legatus to Quintus Lutatius Catulus (who was consul at the time) and pro consule in Gallia Cisalpina;

- 101 BC: Took part in the defeat of the Cimbri at the Battle of Vercellae

- 97 BC: Praetor urbanus

- 96 BC: Propraetor of the province of Cilicia, pro consule;

- 90-89 BC: Senior officer in the Social War, as legatus pro praetore;

- 88 BC:

- Holds the consulship for the first time, with Quintus Pompeius Rufus as colleague

- Invades Rome and outlaws Marius

- 87 BC: Commands Roman armies to fight King Mithridates of Pontus

- 86 BC: Participates in the sack of Athens, the battle of Chaeronea and the battle of Orchomenus

- 85 BC: Liberates the provinces of Macedonia, Asia, and Cilicia from Pontic occupation

- 84 BC: Reorganizes the province of Asia

- 83 BC: Returns to Italy and undertakes civil war against the factional Marian government

- 83-82 BC: Enters war with the followers of Gaius Marius the Younger and Cinna

- 82 BC: Obtains victory at the battle of the Colline Gate

- 82/81 BC: Appointed dictator legibus faciendis et rei publicae constituendae causa

- 80 BC: Holds the consulship for the second time, with Metellus Pius as colleague;

- 79 BC: Resigns the dictatorship and retires from political life, refusing the post consulatum provincial command of Gallia Cisalpina he was allotted as consul, but retaining the curatio for the reconstruction of the temples on the Capitoline Hill

- 78 BC: Dies, perhaps of an intestinal ulcer, with funeral held in Rome

See also[]

References[]

- ^ Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, p. 456-457

- ^ Valerius Maximus, 9.3.8

- ^ Appian, 1.105

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, 6.10

- ^ Velleius Paterculus, 2.17.2

- ^ Jump up to: a b Vervaet, p. 60–68.

- ^ The name Felix – the fortunate – was attained later in life, as the Latin equivalent of the Greek nickname he had acquired during his campaigns, ἐπαφρόδιτος (epaphroditos), that is, beloved of Aphrodite or Venus (to Romans) – due to his skill and luck as a general.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Plutarch • Life of Sulla". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ Smith, William (1870). Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. 3. Boston, Little. p. 933.

- ^ Smith, William. Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. p. 665.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Arthur Keaveney, Sulla: The Last Republican, p. 165

- ^ Keaveney, Arthur. Sulla: The Last Republican. p. 6.

- ^ Keaveney, Arthur. Sulla: The Last Republican. pp. 9–10.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla

- ^ Plutarch (2006). Fall of the Roman Republic. Penguin Classics. p. 59.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, section 2

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, section 3

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Sertorius and the Struggle for Spain, p. 14-15

- ^ Keaveney, p. 30

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 72

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 72-74

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 75-76

- ^ Olbrycht (2009), p. 174-179

- ^ Olbrycht (2009), p. 173

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 77

- ^ Plutarch, Parallel Lives, Life of Sulla

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 95-96

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 89

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 89-90

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 105

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 91-92

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 93

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 107

- ^ [1]

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 90-94

- ^ Stefano Giuntoli, Art & History of Herculaneum

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 109

- ^ Tom Holland, Rubicon, p. 65

- ^ Lynda Telford, A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 97

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lynda Telford, A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 99

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 100

- ^ Jump up to: a b Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 96

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Tom Holland, Rubicon, p. 66

- ^ Jump up to: a b Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 116

- ^ Tom Holland, Rubicon, p. 67

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 116-117

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 98-99

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 100-101

- ^ Tom Holland, Rubicon, p. 67-68

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 116-118

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 101-102

- ^ Tom Holland, Rubicon, p. 68-69

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 117-118

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, p. 35

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 101-104

- ^ Tom Holland, Rubicon, p. 69-73

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Mithridates the Great, Rome's Indomitable Enemy, p. 55

- ^ Tom Holland, Rubicon, p. 69

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, p. 14

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Mithridates the Great: Rome's Indomitable Enemy, p. 77

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 157

- ^ Philip Matyszak, Cataclysm 90 BC, p. 113

- ^ Mark Davies; Hilary Swain (22 June 2010). Aspects of Roman history, 82 BC-AD 14: a source-based approach. Taylor & Francis. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-415-49693-3. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Anthony Everitt, Cicero, p. 41

- ^ Plutarch, Roman Lives, Oxford University Press, 1999, translation by Robin Waterfield. p. 210.

- ^ Suetonius, The Life of Julius Caesar, 1, Archived 2012-05-30 at archive.today

- ^ Plutarch, The Life of Caesar, 1

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Abbott, p. 104

- ^ Abbott, p. 103

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Abbott, p. 105

- ^ Lacus Curtius, Pomerium

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, p. 34

- ^ Suetonius, Julius, 77, Archived 2012-05-30 at archive.today. "...no less arrogant were his public utterances, which Titus Ampius records: that the state was nothing, a mere name without body or form; that Sulla did not know his ABC when he laid down his dictatorship; that men ought now to be more circumspect in addressing him, and to regard his word as law. So far did he go in his presumption, that when a soothsayer once reported direful inwards [sic] without a heart, he said: "They will be more favorable when I wish it; it should not be regarded as a portent, if a beast has no heart..."

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, p. 37

- ^ Jump up to: a b Valerius Maximus, Memorable Deeds and Sayings, 9.3.8

- ^ Pliny the Elder, on Natural History, says that "was not the close of his life more horrible than the sufferings which had been experienced by any of those who had been proscribed by him? His very flesh eating into itself, and so engendering his own punishment."

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Sulla, p. 36-37

- ^ Appian, Bellum Civile, 1.12.105

- ^ Keaveney (2005), Sulla: The Last Republican, 2nd edition, p. 175

- ^ "Plutarch, Sulla, chapter 36". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2015-12-09.

- ^ Robin Seager, "Sulla", in The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume IX (2nd Edition), Cambridge University Press, 1994, p. 207

- ^ Will Durant (2001), Heroes of History: A Brief History of Civilization from Ancient Times to the Dawn of the Modern Age

- ^ Lynda Telford, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, p. 199

- ^ Cicero, Ad Atticum, 9.10.2

- ^ Arthur Keaveney (1982). Sulla, The Last Republican. p. 228. ISBN 978-0-7099-1507-2. Retrieved 10 August 2011.

- ^ Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 22.3

- ^ Michael Crawford, Roman Republican Coinage, 1974, vol. 1, p. 449-451

- ^ Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince, chapter XVIII

- ^ Keaveney, p. 8

- ^ Keaveney, Sulla: The Last Republican, p. 10

- ^ Erik Hildinger, Swords Against the Senate: The Rise of the Roman Army and the Fall of the Republic, Da Capo Press, 2003, p. 99

- ^ "Plutarch, Life of Sulla". May 2008. Retrieved 2011-07-03.

- ^ Keaveney, Sulla: The Last Republican

- ^ Plutarch, Roman Lives, Oxford University Press, 1999, translation by Robin Waterfield. p. 181.

- ^ Keaveney, Sulla: The Last Republican, p. 11

Further reading[]

- Crawford, Michael, Roman Republican Coinage, Cambridge University Press, 1974.

- Fröhlich, Franz, "Cornelius 392", Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft, volume 7 (IV.1), Metzlerscher Verlag (Stuttgart, 1900), columns 1522–1566.

- Keaveney, Arthur (2005) [1982]. Sulla: The Last Republican (2nd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-33660-0.

- Seager, Robin (1994). "Sulla". In J.A. Crook; Andrew Lintott & Elizabeth Rawson (eds.). The Cambridge Ancient History IX: The Last Age of the Roman Republic, 146–43 B.C. (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 165–207. ISBN 0-521-25603-8.

- Telford, Lynda, Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered, Pen and sword; 1st edition (April 19, 2014). ISBN 978-1-783-03048-4.

- Vervaet, Frederik Juliaan (2004). "The lex Valeria and Sulla's empowerment as dictator (82–79 BCE)". Cahiers du Centre Gustave Glotz. 15: 37–84. doi:10.3406/ccgg.2004.858. eISSN 2117-5624.

- Sulla the Fortunate: Roman general and dictator by G. P. Baker (1927, 2001: ISBN 0815411472)

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links[]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Sulla |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sulla. |

- Sulla

- 138 BC births

- 78 BC deaths

- 2nd-century BC Romans

- 1st-century BC Romans

- 1st-century BC rulers

- Ancient Roman dictators

- Ancient Roman generals

- Cornelii Sullae

- Leaders who took power by coup

- Optimates

- Roman patricians

- Roman Athens

- Roman governors of Cilicia

- Roman governors of Hispania

- Roman Republican consuls

- Roman Republican praetors

- Romans who received the grass crown

- Memoirists