Surf's Up (album)

| Surf's Up | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Studio album by the Beach Boys | ||||

| Released | August 30, 1971 | |||

| Recorded | November 1966 – July 1971 | |||

| Studio | Beach Boys, Sunset Sound, Western, and Columbia, Los Angeles | |||

| Genre |

| |||

| Length | 33:49 | |||

| Label | Brother/Reprise | |||

| Producer | The Beach Boys | |||

| The Beach Boys chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Singles from Surf's Up | ||||

| ||||

Surf's Up is the 17th studio album by American rock band the Beach Boys, released August 30, 1971 on Brother/Reprise. It received largely favorable reviews and reached number 29 on the US record charts, becoming their highest-charting LP of new music in the US since 1967. In the UK, Surf's Up peaked at number 15, continuing a string of top 40 records that had not abated since 1965.

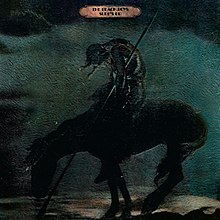

The album's title and cover artwork (a painting based on the early 20th-century sculpture "End of the Trail") are an ironic, self-aware nod to the band's early surfing image.[3] Originally titled Landlocked, the album took its name from the closing track "Surf's Up", a song originally intended for the group's unfinished album Smile. Most of Surf's Up was recorded from January to July 1971. In contrast to the previous LP Sunflower, Brian Wilson was not especially active in the production, which resulted in thinner vocal arrangements.

Lyrically, Surf's Up addresses environmental, social, and health concerns more than the group's previous releases.[3] This was at the behest of newly recruited co-manager Jack Rieley, who strove to revamp the group's image and restore their public reputation following the dismal reception to their recent albums and tours. His initiatives included a promotional campaign with the tagline "it's now safe to listen to the Beach Boys" and the appointment of Carl Wilson as the band's official leader. The record also included Carl's first major song contributions: "Long Promised Road" and "Feel Flows".

Two singles were issued in the US: "Long Promised Road" and "Surf's Up". Only the former charted, when it was reissued with the B-side "Til I Die" later in the year, peaking at number 89. In 1993, Surf's Up was ranked number 46 in NME's list of the "Top 100 Albums" in history. In 2000, it ranked number 230 in Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums. As of 2021, it is ranked as the 761st highest rated album of all time on Acclaimed Music. Session highlights, outtakes, and alternate mixes from the album were collected for the 2021 compilation Feel Flows.

Background[]

On the evening of July 29, 1970, Brian Wilson, accompanied by Mike Love and Bruce Johnston, granted his first-ever full-length radio interview to KPFK DJ John Frank, also known as Jack Rieley.[4] In the interview, Wilson mentioned that although he is "proud of the group and the name", he felt that "the clean American thing has hurt us. And we're really not getting any kind of airplay today."[4] Among other topics, Wilson intimated that the group was not "putting enough spunk in our production and I don't know who to blame. ... Another thing is that we haven't done enough to change our image, though. ... we sort of operate a democracy thing in our productions. Maybe that's the problem. I don't know."[4] The subject eventually turned to "Surf's Up", an unreleased song from the band's unfinished album Smile. Brian said he did not want to release the song because it was "too long".[4]

It sounds silly, but people in America at this time were afraid to listen to the Beach Boys. 20/20 and Sunflower were real disasters sales-wise. But Sunflower was one of the finest recordings I have ever heard by anybody. So, I changed the group.

—Band manager Jack Rieley, 1974[5]

On August 8, Rieley sent the band a six-page memo that explained how to stimulate "increased record sales and popularity".[6] At the end of August, the group's latest record Sunflower was released as their first album on Reprise Records. It became the worst-selling album in the group's history.[7] Band promoter and co-manager Fred Vail remembered one meeting with the band in which "we were talking about ... Sunflower not charting, and they were wondering why. I said to them, 'Listen, this is a phase right now. If you stay the course, your real audience won't forget you. They won't desert you.' But the Beach Boys really didn't believe in themselves."[8] Vail was soon replaced by Rieley, primarily at the instigation of Love and Johnston.[9][nb 1]

Some of Rieley's earliest initiatives were to end the group's practice of wearing matching stage uniforms and to appoint Carl Wilson as the band's official leader.[5] The group spent the majority of September and October rehearsing for upcoming concerts.[5] On October 3, at the invitation of Van Dyke Parks, the band performed two sets at the eighth annual Big Sur Folk Festival in California to an audience of 6,000. According to music historian Keith Badman, the performances "help[ed] to establish the group's image in the eyes of the rock hierarchy, and they are subsequently 'rediscovered' as an important live act."[5][nb 2] Biographer David Leaf wrote that the concert inspired what was effectively an apologetic review from Rolling Stone co-founder Jann Wenner, who previously criticized the band for pulling out of the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival.[12]

In early November, Brian temporarily rejoined the touring band in playing four dates at the Whiskey A Go Go.[13] The group had not played a concert in Los Angeles since 1966, while Brian had not performed with the touring group since early 1970, when he briefly filled in for Love.[14][nb 3] These performances served as a warm-up to the band's second major tour of the year, which lasted from November 19 to December 20, around the UK and Europe. Guitarist Ed Carter and keyboardist Daryl Dragon accompanied the band for this tour, along with supporting act the Flame.[15][nb 4] Reports from this period suggested that the group were planning to move from Los Angeles to Britain once their recording commitments were finished.[17][nb 5] From January to early April 1971, they worked intermittently on their second album for Reprise.[18]

Production and style[]

Surf's Up was recorded between January and July 1971, with the exception of a few tracks.[18][nb 6] After the release of Sunflower, band engineer Stephen Desper assembled a collection of songs consisting mostly of outtakes deemed suitable for a follow-up LP, which he labelled "Second Brother Album".[20][nb 7] Rieley later called these selections "forgettable" and said that he was "totally perplexed ... I met with [Warner executive] Mo Ostin, a true Brian Wilson fan, at Warner Brothers, who listened to the songs, and he declared: 'No way.'"[5]

Rieley encouraged them to write songs with more socially conscious and topical lyrics,[5] although he stated in a 2013 interview, "It was not part of a master plan. ... We never had any 'What are we gonna write about?' meeting. Never once did anything like that ever occur."[22] He assigned the project the brief working title of Landlocked to represent "a demarcation line, separating striped-shirted bullshit that had become irrelevant, an object of public scorn, from artistry, creativity and great new songs."[5] An album cover was designed with this title, featuring white san-serif letters printed atop a photograph of a dark field.[5][nb 8] It was ultimately discarded in favor of a different design. Rieley said that the final cover "was something that caught my eye at an antique record shop near Silver Lake. It was a painting and I bought it. It reminded me a bit of the Brother Records logo, but it was different."[23] Surf's Up was the first album for which the group printed the lyrics of each song on the record sleeve.[24]

In 1974, Rieley stated that his growing involvement with the songwriting process attracted the ire of Love, Johnston, and Al Jardine, who "tried to force me to march into Mo Ostin's and sell him on their 1969 track 'Loop De Loop'". I refused and Brian, Dennis, and Carl backed me up."[18] Due to Brian's reduced involvement, the vocal arrangements were not as dense as those for Sunflower. Johnston recalled, "It was strange to be doing vocal arrangements to make it sound like the Beach Boys when we were the Beach Boys. That's a little weird to me."[25]

January–April sessions[]

"Til I Die" was a song Brian had been working on since mid-1970.[26] It was written while he was suffering from an existential crisis, having recently threatened to drive his car off the Santa Monica pier and ordered his gardener to dig a grave in his backyard.[18][nb 9] He spent weeks arranging "Til I Die", using an electronic drum machine and crafting a harmony-driven, vibraphone and organ-laden background.[29] The group initially rejected the song.[26] According to Johnston, "one member of the band didn't understand it and put it down, and Brian just decided not to show it to us for a few months. ... He was absolutely crushed."[25]

"Long Promised Road" and "Feel Flows" were Carl's first significant solo compositions and were recorded almost entirely by himself.[6] "Student Demonstration Time" (a topical reworking of Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller's R&B classic "Riot in Cell Block Number 9") and the environmental anthem "Don't Go Near the Water" found Love and Jardine embracing the group's new socially conscious direction.[6] Rieley said that "Student Demonstration Time" "had Carl and I blushing with embarrassment", while Dennis was "thoroughly disgusted".[18] Brian disliked the song, saying that the lyrical content was "too intense", but enjoyed "Don't Go Near the Water".[6] Jardine also contributed "Lookin' at Tomorrow (A Welfare Song)", co-written with Gary Winfrey. Biographer Timothy White wrote that the song was "a poignant mini-soliloquy from a jobless rounder, seems like a coda to Long Promised Road, the pioneer busted in his starry-eyed ambitions but still “looking at tomorrow” for a fresh potential."[6] Jardine said that it was "actually an old folk song" to which he "rewrote the lyrics to reflect the times".[31]

"A Day in the Life of a Tree", written by Brian and Rieley, is about a tree succumbing to the effects of environmental pollution. A harmonium, an antique pump organ, and a smaller pipe organ provide accompaniment.[32] In the opinion of critic John Bush, the song's subject appeared to be autobiographical: "one of Brian's most deeply touching and bizarre compositions...lamenting his long life amid the pollution and grime of a city park while the somber tones of a pipe organ build atmosphere."[33] According to Jardine, Rieley sang the song when "no one [else] would sing it because it was too depressing."[34] Leaf quoted an anonymous friend of Brian's saying that Brian was "choked up" after hearing Rieley's vocal performance of the song, because "he [Brian] really related to the song. It was about him."[35]

June–July sessions[]

The recording sessions initially concluded in April, but unexpectedly resumed in June.[36] Rieley had asked Brian about including "Surf's Up" on Landlocked, and in early June, Brian suddenly gave approval for Carl and Rieley to finish the song.[37] While on a drive to meet Mo Ostin, Brian said to Rieley: "Well, OK, if you're going to force me, I'll ... put 'Surf's Up' on the album." Rieley asked, "Are you really going to do it?" to which Brian repeated, "Well, if you're going to force me."[37] According to Rieley: "We got into Warner Brothers and, with no coaxing at all, Brian said to Mo, 'I'm going to put 'Surf's Up' on the next album.' I think this was a great thing because it did provide a commitment on Brian's part and he became more active in the studio."[37]

"Disney Girls (1957)" was recorded during this juncture. Johnston said he wrote the song "because I saw so many kids in our audiences being wiped out on drugs" and wanted to capture the feeling of an era in which people were "a little naive but a little healthier."[38] Brian later praised the song for its harmonies and chords.[6] Further work was also done on Jardine's "Take a Load Off Your Feet", a Sunflower outtake.[19] Timothy White writes that the song is "a slice of social commentary about rundown bodies as well as sullied beaches, its droll sound effects succeeding where a more heavy-handed scolding would not have done."[6] According to Rieley, Jardine "demanded" the song be included on the album,[18] while Jardine said that the song appeared at Rieley's insistence. Jardine explained, "It's cute, but come on ... for some reason Jack Rieley liked it too and said, 'It's got to be on the album. That's definitely an ecology song.' 'Ecology? A song about your feet?' It's personal ecology."[31]

Brian initially refused to participate in the recording of "Surf's Up", and insisted that Carl take the lead vocal.[39] The group attempted to rerecord the song from scratch. "But we scrapped it", Rieley later said, "because it didn't quite come up to the original."[38] Carl overdubbed a new vocal in the song's first part, the original backing track dating from November 1966. The second movement consisted of a December 1966 solo piano demo recorded by Brian, augmented with vocal and Moog synthesizer overdubs.[40] Johnston recalled, "We ended up doing vocals to sort of emulate ourselves without Brian Wilson, which was kind of silly."[25] To the surprise and glee of his associates, Brian emerged near the end of the sessions to aid Carl and Desper in the completion of the coda, and contributing the song's missing, final lyric.[41] With the song completed, Landlocked was given the new title of Surf's Up.[39]

Leftover material[]

Dennis Wilson's songs "4th of July" and "Wouldn't It Be Nice to (Live Again)" were recorded in early 1971 but left off the record.[43] According to Rieley, the absence of any Dennis songs on Surf's Up was for two reasons: to quell political infighting within the group concerning the album's share of Wilson-brother songs, and because Dennis wanted to save his songs for a solo album, projected for release in 1971. In December 1970, he released the single "Sound of Free" (credited to "Dennis Wilson & Rumbo"), but the album project was ultimately shelved.[44]

"Wouldn't It Be Nice to (Live Again)" was written with Stanley Shapiro. According to Beach Boys biographer Jon Stebbins, Dennis had wanted the song to close the record, following "'Til I Die", but Carl objected.[45] In 2013, it was released for the box set Made in California, along with a 1974 recording of "Barnyard Blues", a song that Dennis had composed during the Surf's Up sessions.[46] Wilson also recorded "Barbara", a piano demo named after his then-girlfriend, and a track called "Old Movie".[43] "Barbara" was released in 1998 for the Endless Harmony Soundtrack.[36]

Other outtakes include "My Solution", a song Brian later reworked as "Happy Days" for his 1998 album Imagination.[13] Brian's "H.E.L.P. Is On the Way" was written about H.E.L.P., a Los Angeles restaurant that the Beach Boys frequented, and mentions the Radiant Radish in the lyric.[47] In 1982, author David Toop remarked that it may be "the only pop song in history to mention enemas".[48] The track was planned for inclusion on the scrapped 1977 album Adult/Child.[49] In 1993, the song was released for the box set Good Vibrations: Thirty Years of the Beach Boys.[5]

According to singer Terry Jacks, the group asked him to be their producer for a session. On July 31, 1970 they attempted a rendition of the Jacques Brel/Rod McKuen song "Seasons in the Sun", but the session went badly, and the track was never finished. Jacks later had a hit with his own version of the song in 1974.[4] Afterward, Mike Love told an interviewer: "We did record a version [of 'Seasons'] but it was so wimpy we had to throw it out. ... It was just the wrong song for us. I'm glad Terry had a hit with it."[20] Love's "Big Sur", recorded in August 1970, marked the first time he had written both the music and words to a song. It was rerecorded in a different time signature for the 1973 album Holland.[50] In March 1971, Carl recorded a Moog synthesizer sound collage titled "Telephone Backgrounds (On a Clear Day)".[36]

Release[]

Rieley arranged for the group to appear in a series of commercials with the tagline "It's now safe to listen to the Beach Boys."[5] He also arranged a guest appearance at a Grateful Dead concert at Bill Graham's Fillmore East in April 1971 to foreground the band's transition into the counterculture.[51] For their performances this year, the Beach Boys enlisted a full horn section and additional percussionists.[52] A journalist who attended the show later reported that Bob Dylan, who was watching from the sound booth, remarked aloud, "You know, they're pretty fucking good."[53][nb 10] Contrary to what is later written of the show, the Grateful Dead's audience was unfavorable toward the Beach Boys' appearance.[53] On May 1, the band performed at The Peace Treaty Celebration Rock Show, an anti-war rally concert organized by the Mayday Collective, with approximately 500,000 people in attendance. Footage of the band performing "Student Demonstration Time" later appeared in the 1985 documentary An American Band.[53][nb 11]

On May 24, "Long Promised Road" (B-side "Deirdre") was issued as lead single, becoming their sixth consecutive US single that failed to chart.[37] That same month, Dennis accidentally punched his hand through a glass window, severing nerves and tendons. The injury left him unable to play drums for the band, and so he was replaced by the Flame's Ricky Fataar. Dennis continued to make occasional appearances at concerts, singing or playing keyboards.[39] In July, the American music press rated the Beach Boys "the hottest grossing act" in the country, alongside Grand Funk Railroad.[23] On July 7, the film Two-Lane Blacktop, co-starring Dennis, made its worldwide premier in New York City. Despite critical acclaim, the film was largely unnoticed by cinema-goers.[23]

Surf's Up was released on August 30 to more public anticipation than the Beach Boys had had for several years.[1] Aided by some FM radio exposure,[6] it outperformed Sunflower commercially and was their best selling album in years.[1] On September 6, Time reported that the album was "doing well enough. Barely out, it is fast approaching $250,000 in sales."[42] From September 22 to October 2, the band toured the eastern US, but the performances received mixed reviews. Their setlists included every song from the album except "Til I Die" and "A Day in the Life of a Tree".[56] Dennis also played solo piano renditions of his unreleased songs "Barbara" and "I've Got a Friend".[52]

On October 28, the Beach Boys were the featured cover story on that date's issue of Rolling Stone. It included the first part of a lengthy two-part interview, titled "The Beach Boys: A California Saga", conducted by journalists Tom Nolan and David Felton.[57][nb 12] Unusually, the story devoted minimal attention to the group's music, and instead focused on the band's internal dynamics and history, particularly around the period when they fell out of step with the 1960s counterculture.[58][nb 13] At the end of the month, Surf's Up peaked on the US charts at number 29, becoming their highest-charting album there since Wild Honey (1967).[59]

In the UK, Surf's Up was released by EMI's Stateside label in October and peaked at number 15.[23] Rieley was unhappy with the delay, remarking that the album "sold more import copies than they sold of British pressings."[42] The UK singles, "Long Promised Road" (B-side "Deirdre") and "Don't Go Near the Water" (B-side "Student Demonstration Time"), failed to chart.[60] In November, "Surf's Up" (B-side "Don't Go Near the Water") was released as the last US single and failed to chart.[57]

Contemporary reviews[]

Surf's Up received generally favorable reviews.[1] Time's reviewer described it as "one of the most imaginatively produced LPs since last fall's All Things Must Pass by George Harrison and Phil Spector".[42] A Rolling Stone writer stated: "the Beach Boys stage a remarkable comeback ... an LP that weds their choral harmonies to progressive pop and which shows youngest Wilson brother Carl stepping into the fore of the venerable outfit."[1] In his review for the magazine, Arthur Schmidt was effused with the record, highlighting "Surf's Up" and "Disney Girls" as his favorite songs, and wrote: "This is a good album, probably as good as Sunflower, which is terrific ... It is certainly the most original in that it has contributed something purely its own."[24] Richard Williams of The Times called the record "mostly very good" in his review;"[61] in another review of the album from 1972, he wrote that it "won't disappoint anyone at all ... they've produced an album which fully backs up all that's recently been written and said about them."[62] NME's Richard Green called it a "very good album, very different from anything they've done before."[63]

Robert Christgau was less impressed in The Village Voice. While highlighting "Take a Load Off Your Feet" and "Disney Girls (1957)", he found most of the other songs forgettable and the album the group's worst since 1968's Friends, before writing, "Van Dyke Parks's wacked-out lyricist meandering is matched by the sophomoric spiritual quest of Jack Rieley, and the music drags hither and yon."[64] In The Rag, Metal Mike Saunders lamented that most of the press furor over the Beach Boys' reputed comeback "has been rubbish" and opined that Surf's Up suffered from the same issues as Sunflower, namely "horrendous production and engineering" and a lack of "focus". He wrote, "At any rate, the Brian Wilson Enigma remains unanswered, and the Beach Boys without him are just another rock group."[65] The Guardian's Geoffrey Cannon felt that the album was inconsistent[66]

Retrospective assessments and legacy[]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Christgau's Record Guide | B–[68] |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound Rock | 4/5[70] |

| Pitchfork (Sunflower/Surf's Up reissue) | 8.9/10[3] |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

In 1974, the staff of NME ranked Surf's Up number 96 in their list of the "Top 100 Albums" of all time. When the magazine surveyed its writers again in 1993, the album's position rose to number 46.[72] In 2000, the record was voted number 230 in the third edition of Colin Larkin's All Time Top 1000 Albums.[73] In 2004, Surf's Up was ranked number 61 on Pitchfork's list of "The Top 100 Albums of the 1970s". Contributor Dominique Leone wrote:

Surf's Up practically defines flawed greatness, via Carl Wilson's introspective, exotic folk-pop, manager Jack Rieley's devastating vocal on Brian's “A Day in the Life of a Tree,” and Brian's own gorgeous “’Til I Die”—which might very well go down as his last truly great production. Today the eclectic, relaxed sound of this album is reflected in the work of Super Furry Animals, Stereolab, and Sufjan Stevens, but its power comes from the shy passion and sincere, spiritual convictions of its creators.[74]

Music critic John Bush wrote "[Most of the] songs are enjoyable enough, but the last three tracks are what make Surf's Up such a masterpiece."[67] Mojo critic Ross Bennett regarded Surf's Up as "the definitive version" of the Smile recordings, "with those crystalline vocals imbuing Parks' cryptic verses with a grace and simplicity missing from the 2004 reboot".[75] Keith Phipps from The A.V. Club called it "the darkest album of the group's career, a record that also spotlighted a growing social conscience".[76]

Conversely, Scott Schinder wrote in Icons of Rock (2006) that Surf's Up "lacked the solid group dynamic that had elevated Sunflower" despite two "impressive songwriting contributions from Carl".[77] James E. Perone, writing in The 100 Greatest Bands of All Time (2015), opined that "the album's lyrical themes are so wide ranging that the social commentary tended to get somewhat lost, and the year 1971 was late enough in the counterculture era that 'Student Demonstration Time' and 'A Day in the Life of a Tree' seem like a case of too little, too late."[78] Stebbins opined that the album suffered from a lack of Dennis songs and was not as strong as Sunflower in its totality.[79] Record Collector's Jamie Atkins said that the lack of Dennis songs was balanced by the strong offerings from Carl, although Rieley's "awkward wordplay ... was rather less clever than he had perhaps intended. Happily, they did not detract from the quality of the songs:"[80]

Surf's Up was the last Beach Boys album recorded with Bruce Johnston until 1979's L.A. (Light Album). He later criticized the record: "To me, Surf's Up is, and always has been, one hyped up lie! It was a false reflection of The Beach Boys and one which Jack [Rieley] engineered right from the start. ... It made it look like Brian Wilson was more than just a visitor at those sessions. Jack made it appear as though Brian was really there all the time."[42][nb 14] In another interview, Johnston said: "All I can say is that at the beginning, I thought that what he was trying to do was absolutely right on the money. He helped the band become aware of what our niche was in pop music."[35]

The record is also listed in the musical reference book 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die.[81] In 2014, John Wetton named Surf's Up his favorite prog album of all-time, elaborating: "The summer of '71 had so many musical milestones ... but Surf's Up was a revelation. I was in Family, a major player in the first wave of British progressive bands, but this collection from the iconic California surf-pop band shifted my parameters, blurring all the boundaries of my musical vocabulary. ... And the cover? Mega prog!"[82] As of 2020, it is listed as the 699th-highest rated album of all time on Acclaimed Music.[83]

Track listing[]

Original release[]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocal(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Don't Go Near the Water" | Mike Love, Al Jardine | Mike Love, Al Jardine, Brian Wilson | 2:39 |

| 2. | "Long Promised Road" | Carl Wilson, Jack Rieley | Carl Wilson | 3:30 |

| 3. | "Take a Load Off Your Feet" | Jardine, Brian Wilson, Gary Winfrey | B. Wilson, Jardine | 2:29 |

| 4. | "Disney Girls (1957)" | Bruce Johnston | Bruce Johnston | 4:07 |

| 5. | "Student Demonstration Time" | Jerry Leiber, Mike Stoller, Love | Love | 3:58 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocal(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | "Feel Flows" | C. Wilson, Rieley | C. Wilson | 4:44 |

| 2. | "Lookin' at Tomorrow (A Welfare Song)" | Jardine, Winfrey | Jardine | 1:55 |

| 3. | "A Day in the Life of a Tree" | B. Wilson, Rieley | Jack Rieley, Van Dyke Parks, Jardine | 3:07 |

| 4. | "'Til I Die" | B. Wilson | C. Wilson, B. Wilson, Love | 2:31 |

| 5. | "Surf's Up" | B. Wilson, Van Dyke Parks | C. Wilson, B. Wilson, Jardine | 4:12 |

| Total length: | 33:49 | |||

Feel Flows[]

In 2021, expanded editions of Sunflower and Surf's Up were packaged within Feel Flows, a box set that includes session highlights, outtakes, and alternate mixes drawn from the two albums. The set also includes the first ever releases of the Surf's Up-era outtakes "Big Sur" (1970 version), "Sweet and Bitter", "My Solution", "Seasons in the Sun", "Baby Baby", "Awake", and "It's a New Day".[84][better source needed]

Personnel[]

Partial credits per Timothy White and 2000 liner notes,[6] except where otherwise noted.

The Beach Boys

- Al Jardine

- Bruce Johnston

- Mike Love

- Brian Wilson

- Carl Wilson

- Dennis Wilson

Additional musicians and production staff

- The Beach Boys – producer

- Stephen Desper – chief engineer and mixer

- Van Dyke Parks – vocals on "A Day in the Life of a Tree"[85]

- Jack Rieley – lead vocals on "A Day in the Life of a Tree" and backing vocals in "Surf's Up" tag[39]

- Ed Thrasher – original art direction

Charts[]

| Chart (1971) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| UK Top 40 Albums[23] | 15 |

| US Billboard 200[23] | 29 |

References[]

Notes

- ^ Nick Grillo remained the band's business manager until December 1971.[10]

- ^ From August 13 to late October, Dennis shot his parts for the Universal Pictures road movie Two-Lane Blacktop. Due to these commitments, he did not attend the rehearsals or the concerts, and was filled in by Mike Kowalski.[11]

- ^ Brian only played the first two nights, as he experienced a panic attack on the second.[13]

- ^ Rieley later told a radio interview, "From an artistic stance, it was a disastrous tour" due to the Beach Boys' dissatisfactory performances.[16]

- ^ In one report, Rieley said they were "definitely leaving Los Angeles because of the smog."[17]

- ^ "Surf's Up" (portions recorded in 1966), "Take a Load Off Your Feet" (portions recorded in January 1970), "Til I Die" (portions recorded in August 1970), and "Student Demonstration Time" (portions recorded in November 1970).[19]

- ^ These songs were "Loop de Loop", "Susie Cincinnati", "San Miguel", "H.E.L.P. Is On the Way", "Take a Load Off Your Feet", "Carnival", "I Just Got My Pay", "Good Time", "Big Sur", "Lady", "When Girls Get Together", "Lookin' at Tomorrow", and "'Til I Die".[21]

- ^ It was long thought that Landlocked was a complete album that was scrapped by the Beach Boys in between Sunflower and Surf's Up, but this was not true.[21] Writing in The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary, Keith Badman states that Landlocked was nothing more than a provisional title for Surf's Up,[5] and in a February 1970 interview, the group referred to the Second Brother Album acetate as tracks that "might be on an album, but it's not a new album".[20]

- ^ According to Leaf, these episodes were treated as jokes by Wilson's family and friends.[27] In a November 1970 interview, Brian discussed his daily routine of "go[ing] to bed in the early hours of the morning and sleep[ing] until the early afternoon". He said: "I'm not unhappy with life; in fact I'm quite happy living at home."[28]

- ^ Biographer Steven Gaines wrote that the bootlegged tape of this concert "became legendary in the rock-and-roll business."[1]

- ^ The Beach Boys were the only major group to appear at the rally. David Leaf wrote: "People were shaking their heads in disdain when it was announced that the Beach Boys were going to play ... All of a sudden", following the concert, "the Beach Boys were relevant."[54] According to Keith Badman, the group's status "as a notable live act" was restored with this concert, and it was held just two days after performing to one of their smallest ever crowds, in Maryland, for an audience of 200.[53]

- ^ The second part was published for the issue dated November 11.[57]

- ^ According to journalist David Hepworth, the style was unprecedented in the field of music writing, and the "story within was destined to become a classic piece from that brief interlude when pop writing collided with New Journalism ... It combined admiration for the group's achievements with distaste for their strange, inner world in a way that hadn't been done before".[58]

- ^ From a performance standpoint, he cited 1971 as his favorite year of the group musically because their set lists focused on newer songs.[52]

Citations

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Gaines 1986, p. 242.

- ^ Furman, Michael. "The Beach Boys - Surf's Up". Tiny Mix Tapes. Retrieved February 29, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Macauley, Hefner (July 18, 2000). "The Beach Boys: Sunflower/Surf's Up | Album Reviews". Pitchfork. Retrieved February 19, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Badman 2004, p. 273.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k Badman 2004, p. 277.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i White, Timothy (2000). Sunflower/Surf's Up (CD Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 154.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 275.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 275, 277.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 301.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 274, 277.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 138.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Badman 2004, p. 278.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 264, 278.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 282.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Badman 2004, p. 283.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Badman 2004, p. 288.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sessionography:

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Badman 2004, p. 274.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Doe, Andrew G. (2012). "UNRELEASED". Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- ^ "The Life of RIELEY". Record Collector Mag. September 6, 2013.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g Badman 2004, p. 297.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Schmidt, Arthur (October 14, 1971). "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up". Rolling Stone.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Leaf 1978, p. 144.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Carlin 2006, p. 161.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 147.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 279.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 162.

- ^ "The Beach Boys: The River's A Dream In A Waltz Time". Aquarium Drunkard. March 14, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sharp, Ken (July 28, 2000). "Alan Jardine: A Beach Boy Still Riding The Waves". Goldmine.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 160.

- ^ Bush, John. "Surf's Up review". Allmusic. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ^ The Playlist Special, Rolling Stone

- ^ Jump up to: a b Leaf 1978, p. 146.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Badman 2004, p. 289.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Badman 2004, p. 291.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Badman 2004, p. 292.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Badman 2004, p. 296.

- ^ Carlin 2006, pp. 162–163.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 163.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Badman 2004, p. 298.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Badman 2004, pp. 288–289.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 279, 283, 298.

- ^ Stebbins 2011, p. 165.

- ^ "Beach Boys Producers Alan Boyd, Dennis Wolfe, Mark Linett Discuss 'Made in California' (Q&A)". Rock Cellar Magazine. September 4, 2013. Archived from the original on 30 September 2013. Retrieved 9 September 2013.

- ^ Richmond, Akasha (2006). Hollywood Dish: More Than 150 Delicious, Healthy Recipes from Hollywood's Chef to the Stars. Penguin. p. 70. ISBN 978-1-4406-2814-6.

- ^ Toop, David (1982). "Surfin' Death Valley USA: The Beach Boys and Heavy Friends". In Hoskyns, Barney (ed.). The Sound and the Fury: 40 Years of Classic Rock Journalism: A Rock's Backpages Reader. Bloomsbury USA (published 2003). p. 402. ISBN 978-1-58234-282-5.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 371.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 274, 320.

- ^ Gaines 1986, pp. 241–242.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Leaf 1978, p. 141.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Badman 2004, p. 290.

- ^ Leaf 1978, p. 142.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 243.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 299–300.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Badman 2004, p. 300.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hepworth, David (2016). Never a Dull Moment: 1971 The Year That Rock Exploded. Henry Holt and Company. p. 223. ISBN 978-1-62779-400-8.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 208, 297, 300.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 291, 300.

- ^ Williams, Richard (November 2, 1971). "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up (Stateside SSL 10313, £2.15.)". The Times.

- ^ Williams, Richard (1972). "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up". Melody Maker.

- ^ Green, Richard (November 6, 1971). "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up". NME.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (October 14, 1971). "Consumer Guide (19)". The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Saunders, Metal Mike (November 8, 1971). "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up (Brother/Reprise 6653)". The Rag.

- ^ Cannon, Geoffrey. "Feature: Out of the City". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group (October 29, 1971): 10.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Bush 2002, p. 73.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (1981). "The Beach Boys: Surf's Up". Christgau's Record Guide: Rock Albums of the '70s. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306804093.

- ^ The Virgin Encyclopedia of Popular Music, Concise (4th Edition), Virgin Books (UK), 2002, ed. Larkin, Colin.

- ^ Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel (eds) (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Farmington Hills, MI: Visible Ink Press. p. 83. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- ^ Brackett, Nathan; with Hoard, Christian, eds. (2004). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York, NY: Fireside/Simon & Schuster. p. 46. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- ^ Stebbins 2011, p. [page needed].

- ^ Larkin, Colin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 108. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Leone, Dominique (2004). "Staff Lists: top 100 albums of the 1970s: Surf's Up". Pitchfork. Retrieved 13 March 2012.

- ^ Bennett, Ross. "The Beach Boys - Disc of the day - Mojo". Mojo4music.com. Archived from the original on 10 March 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- ^ Phipps, Keith (April 17, 2002). "The Beach Boys: Sunflower/Surf's Up : Music". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ Schinder, Scott (2007). "The Beach Boys". In Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (eds.). Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 122. ISBN 978-0313338458.

- ^ Perone, James E. (2015). "The Beach Boys". In Moskowitz, David V. (ed.). The 100 Greatest Bands of All Time: A Guide to the Legends Who Rocked the World. ABC-CLIO. p. 45. ISBN 978-1-4408-0340-6.

- ^ Stebbins 2011, pp. 163, 165.

- ^ Atkins, Jamie (July 2018). "Wake The World: The Beach Boys 1967-'73". Record Collector.

- ^ Robert Dimery (2008). "The Seventies". 1001 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (2nd ed.). London: Cassell Illsutrated. p. 234. ISBN 978-1844036240.

- ^ "100 Greatest Prog Albums". Prog. No. 49. 2014.

- ^ "The Beach Boys Surf's Up". Acclaimed Music. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ Iahn, Buddy (June 2, 2021). "THE BEACH BOYS 'FEEL FLOWS' BOX SET DETAILED". The Music Universe. Retrieved June 2, 2021.

- ^ Nolan, Tom (October 28, 1971). "The Beach Boys: A California Saga". Rolling Stone.

Bibliography

- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America's Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6.

- Bush, John (2002). "Surf's Up". In Bogdanov, Vladimir; Woodstra, Chris; Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (eds.). All Music Guide to Rock: The Definitive Guide to Rock, Pop, and Soul. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-653-3.

- Carlin, Peter Ames (2006). Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys' Brian Wilson. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-320-2.

- Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: The True Story of The Beach Boys. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806479.

- Leaf, David (1978). The Beach Boys and the California Myth. New York: Grosset & Dunlap. ISBN 978-0-448-14626-3.

- Stebbins, Jon (2011). The Beach Boys FAQ: All That's Left to Know About America's Band. Backbeat. ISBN 978-1-4584-2918-6.

Further reading[]

- Sheriff, Thomas H. (July 9, 2020). "Low Culture 12: The Beach Boys In The 1970s". The Quietus.

- Goldenberg, Joel (September 12, 2020). "Free Feel Flows!". The Suburban.

External links[]

- 1971 albums

- The Beach Boys albums

- Capitol Records albums

- Reprise Records albums

- Progressive pop albums

- Albums produced by the Beach Boys

- Albums recorded at United Western Recorders

- Albums recorded at Sunset Sound Recorders

- Albums recorded in a home studio